Mar 11, 2019

Suthasinee Kaewleklai, coordinator for Migrant Workers Rights Network (MWRN) in Thailand, recently was honored for her work by the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRCT).

Suthasinee Kaewleklai, MWRN coordinator, recently was honored for her work by the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRCT). Credit: Solidarity Center/Robert Pajkovski

“Migrant workers are among the most vulnerable and abused workers in every country,” says Kaewleklai. “Worker rights are human rights, and migrant workers are entitled to fundamental rights without discrimination, including the freedom of association and collective bargaining. We will fight shoulder to shoulder with our sisters and brothers.”

Kaewleklai received the award during an NHRCT seminar last week, held in conjunction with International Women’s Day to honor women human rights defenders. The nonprofit MWRN, a Solidarity Center partner, has provided a crucial bridge between workers and access to legal redress for unpaid wages, occupational injuries and other forms of workplace abuse since it was founded in 2009.

“Whether they are protecting rights in the judicial process, fighting against impunity for rights violations, protecting democratic freedoms and the rights of communities and migrant workers, or fighting for freedom of expression, equality and the reduction of gender biases, their courageous stories are models and inspirations for future generations to learn and remember,” Angkana Neelapaijit, National Human Rights commissioner, said during the award ceremony.

Risking Physical, Verbal Assaults to Support Workers

Kaewleklai, a long-time trade unionist, began championing worker rights in the 1990s, when she worked at a factory in the Rangsit district, north of Bangkok. A co-founder of the factory’s union, she and other workers successfully challenged their employer’s refusal to regularly pay wages, and she successfully took legal action after the employer fired her and other union activists.

She later worked as coordinator for the Thai Labor Solidarity Committee, another Solidarity Center partner, and has championed the issues of working women, successfully campaigning to make International Women’s Day a national holiday.

At the MWRN, Kaewleklai advocates for the rights of migrant workers to form unions, negotiate with their employers for better working conditions, and urging lawmakers to ratify International Labor Organization standards on freedom of association and collective bargaining. She has helped migrant workers on chicken farms and elsewhere recover unpaid wages and attain safe working conditions.

She repeatedly has been verbally threatened, physically attacked and put under surveillance by state and non-state actors for her work to protect and promote labor rights and the rights of migrant workers. Currently, Kaewleklai, along with 14 migrant workers and other human rights defenders, is challenging criminal and civil charges filed by the poultry company, Thammakaset Company, following her advocacy on behalf of the company’s underpaid migrant workers.

Despite rulings by authorities and the courts against Thammakaset—including a January Supreme Court decision upholding a lower court ruling ordering Thammakaset to pay $53,600 to 14 former migrant workers for violations of the Labor Protection Act—the company continues to pursue charges against Kaewleklai and the others. Human rights defenders believe the charges are part of a strategy to harass human rights defenders and migrant worker rights advocates.

Mar 8, 2019

An independent,12-month monitoring program by a coalition of worker rights advocates in Kyrgyzstan found that the lives and safety of working people are at significantly higher risk than official data indicates—requiring urgent changes to the country’s occupational safety and health (OSH) monitoring system.

“I am asking government to take OSH issues into consideration because they envelop the lives of our workers,” said Eldiyar Karachalov, deputy president of the Kyrgyz union representing construction workers, at a roundtable briefing last month.

The event—which convened worker rights advocates, lawmakers, government administrators and employers for discussions on worker safety—highlighted data collected in 2018 by monitors from Kyrgyz metallurgy and mining, construction, garment and food processing unions and local NGOs Bir Duino Kyrgyzstan and the Insan Leilek Foundation.

According to official labor inspection statistics, 3,808 OSH violations and incidents occurred in 2018. However, the unions’ independent monitoring program found 500 previously unreported OSH violations and incidents—including 155 injuries and 15 deaths. Because most of the unreported OSH incidents occurred in informal-sector workplaces, unions are requesting that the country’s labor monitoring system be expanded into that sector. More than 70 percent of Kyrgyz workers are informal and so have little protection by trade unions or labor laws.

The entity with legal jurisdiction over Kyrgyzstan’s safety inspection system, StateEcoTechInspection, reports limited ability to collect data due to scarce resources. Since 2012, the number of full-time labor inspectors in Kyrgyzstan has fallen from 62 to 23.

“It is absolutely necessary to enlarge the labor inspection authorities and staff,” said Karachalov.

The unions and their NGO partners hope to present their data and recommendations to Parliament during an upcoming hearing on OSH reform. Union recommendations will include a call for adequate funding, an increase in the number of labor inspectors, better training of inspectors, employer-funded safety training for workers and employer-provided personal protective equipment for workers.

According to International Labor Organization (ILO) data, some 2.3 million women and men around the world succumb to work-related accidents or diseases every year, including 340 million victims of occupational accidents and 160 million victims of work-related illnesses. The ILO reports 11,0000 fatal occupational accidents annually in the 12-member states comprising the Commonwealth of Independent States—Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan—but points to “gross underreporting” of occupational accidents and diseases in the region.

Kyrgyzstan is one of the region’s poorest countries. Although the official unemployment rate hovers around 8 percent, more than 1 million Kyrgyz nationals are estimated to be working abroad, particularly in Russia and neighboring Kazakhstan, where wages are higher but conditions for migrant workers can be dire. In Kyrgyzstan, the Solidarity Center aims to strengthen union representation to protect workplace safety and health and secure protections for Kyrgyz workers who migrate for jobs.

Mar 7, 2019

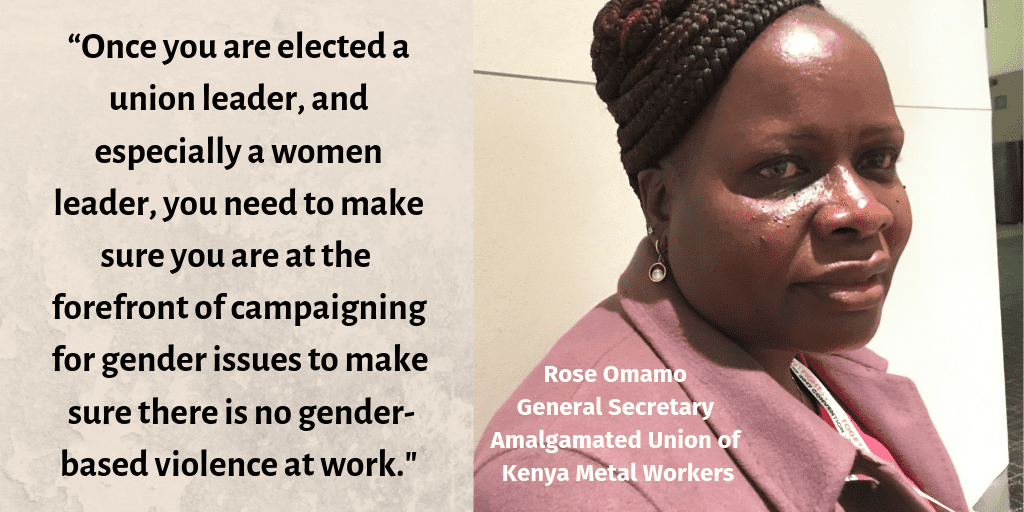

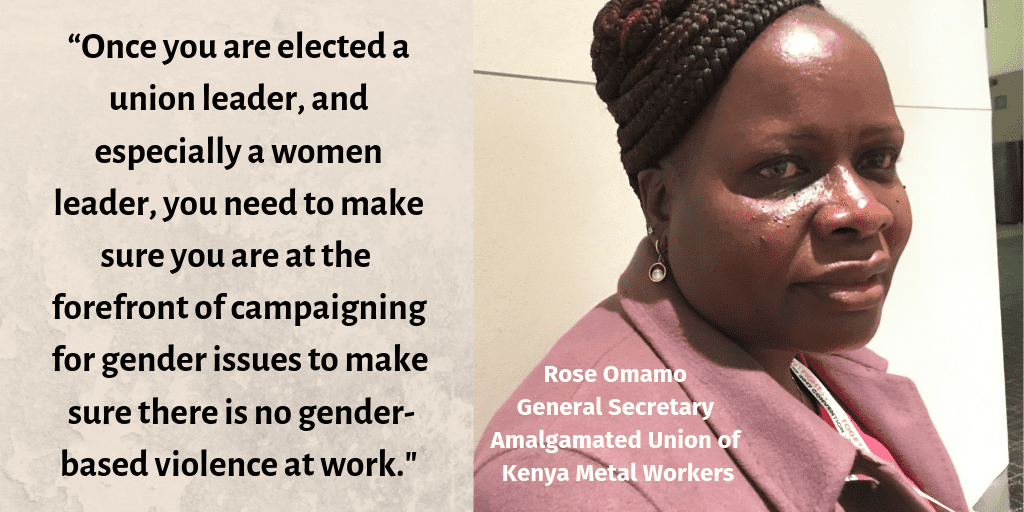

As the international community celebrates March 8, International Women’s Day, Kenya union leader Rose Omamo is meeting with union leaders and government officials across Africa to help propel passage of a proposed global standard that would address gender-based violence at work.

The convention (standard) under consideration by the International Labor Organization (ILO) would end violence and harassment in the workplace. Workers and their unions are championing its adoption with a strong focus on gender-based violence and harassment. Released last week, the most recent draft language of the proposed instrument, “Ending Violence and Harassment in the World of Work” builds on high-level talks in early 2018 among representatives of workers, government and business.

Rose Omamo discussed gender-based violence at work on a Kenya television station in February. Credit: NTV

“We believe we will be able to convince the governments and even some of the employers to support the convention,” says Omamo, general secretary of the Amalgamated Union of Kenya Metal Workers and national Women’s Committee chair of the Congress of Trade Unions–Kenya (COTU-K), a Solidarity Center partner.

In June, representatives of workers, government and business will negotiate final language on a binding convention and recommendation at the International Labor Conference (ILC).

“Our job is to lobby, lobby, lobby and make sure we get support,” says Omamo, who will be among worker representatives at the ILC discussions. She will be joined by union leaders from other Solidarity Center partner unions, including Eulogia Familia, vice president of the Confederación Nacional de Unidad Sindical (National Confederation of Labor UnionUnity, CNUS) from the Dominican Republic, and Fiona Gandiwa Magaya, coordinator of the Zimbabwe Confederation of Trade Unions (ZCTU) Gender Department.

Unions Drive Campaign to End Gender-Based Violence at Work

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue, says Solidarity Center Senior Gender Specialist Robin Runge.

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue, says Solidarity Center Senior Gender Specialist Robin Runge.

Workers and their unions are seeking a definition of violence at work in the final convention that would encompass transportation to and from work, an area in which employer groups are resisting. But Omamo believes it is imperative to include the time in which a worker commutes.

“For example, there was a company where workers reported very early in the morning. When the lady was going to work very early in the morning, when she was just crossing the railroad tracks, she was raped,” says Omamo. “These things are happening to us and are affecting us.”

Other issues include ensuring the final convention encompasses broad definitions of who is covered and what constitutes “violence and harassment.”

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), which has helped coordinate and guide the campaign to end gender-based violence at work, offers information and tools to assist unions and organizations in taking action.

Building Support to End Gender-Based Violence at Work

Omamo and her sisters have been working doggedly over the past year to create awareness of and build support for passage of the convention. Omamo has traveled across Kenya to educate union members, such as engineers in glass, metal and petroleum, about the draft proposal.

As a representative on the gender commission of the Organization of African Trade Union Unity (OATUU), Omamo has met with government officials in Uganda and elsewhere to push for their support of the convention. In April, COTU-Kenya is hosting a meeting of women union unionists from the 18 OATUU member countries who will share input from their discussions with government officials, so the group can determine the level of government support for the convention and identify potential stumbling blocks going into the June ILC meeting.

When meeting individually with government leaders, Omamo says she describes the far-reaching consequences for workers experiencing sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence at work. “Some people even leave jobs because of the kind of harassment they go through at work—not because they don’t want to work, but because the bosses they have are sexually harassing them,” she says.

“Once you are elected a union leader, and especially a women leader, you need to make sure you are at forefront of campaigning for gender issues, make sure there is no gender-based violence at work, and make sure women are working in a safe environment,” says Omamo, who became the first woman to lead her 11,000-member union.

“This is a convention is very close to our hearts.”

Mar 4, 2019

Even as 11,000 Bangladesh garment workers were fired in the wake of strikes they waged in December and January to protest low wages, many seeking to form unions or take collective action also have been physically threatened, attacked and arrested on trumped-up charges. And union leaders say these employer-directed assaults often take the form of gender-based violence at work.

In testimony provided to the Solidarity Center by garment workers and union leaders, a pattern emerges in which women seeking to form unions or engage in collective action are especially targeted with actions to degrade, demean and intimidate them, and some have suffered physical attacks and rape.

“As we try to form unions, management is hostile against us,” says one garment worker. (Neither workers nor factories will be identified to protect workers against retaliation.) “They threaten me that, what if someone stops me in the road, what can I do as a woman?”

Children Injured in Police Attack on Factory

At one factory where workers walked out on January 7 to demand higher wages, police charged them and threw tear gas into the factory, injuring between 13 and 14 children in the ground floor day care. Managers later “sent out a list of all the mothers with babies and terminated them,” says one worker at the factory. “They did this so that they could close down the day care.”

On the same day, at another garment factory where workers say managers had harassed them ever since they submitted a union registration application in November, police beat workers with rods and sticks and “took away the scarves of women,” threatening to rape them, according to a worker’s eyewitness account.

While Bangladesh employers stepped up attacks directed at women workers during the recent walkouts, they have long used gender-based violence at work as a tactic to intimidate women active in union organizing. In November, hired criminals associated with management and local government officials attacked and raped a woman organizer at a factory in the midst of a campaign to form a union.

Crackdown Amplifies Ongoing Assaults on Worker Rights

The harassment, assaults and arrests of garment workers this year amplifies an increasingly repressive environment for worker organizing that in recent years has included threatening home visits, kidnappings and mass termination.

In one recent example, workers at a garment factory saw their daily production quota increased to 400 pieces a day, up from 250 pieces after they filed with the government for union registration. Workers there say supervisors locked union committee members in bathrooms and hired local criminals to pursue them in the streets.

Even as employers exploit workers’ wage protests as a pretext for infringing on the rights of workers to organize and bargain collectively, government resistance to workers seeking to register unions further represses workers’ efforts to form unions and collectively bargain better wages and working conditions.

Following the deaths of more than 1,200 garment workers in the 2012 fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory and the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse, workers vigorously organized to form unions and negotiate contracts, as the Bangladesh government and ready-made garment (RMG) employers responded to international pressure to improve safety and wages.

But now Bangladesh, which in 2018 the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) ranked as among the world’s 10 worst countries for worker rights, is on the verge of expelling the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. Established after the Rana Plaza disaster, the legally binding agreement between hundreds of primarily European retail brands and unions conducted safety inspections at more than 1,000 factories and educated workers on safety and other workplace rights.

And without the freedom to form unions and bargain collectively, internationally recognized rights, Bangladesh garment workers are unable to collectively negotiate safer, healthier workplaces.

“We are poor. Just because we formed a union, we have been the victims,” says one worker at a factory where 200 workers were fired after they sought to register a union with the government. The worker says when management learned of their efforts to form a union, women were threatened with rape and men threatened with guns and knives.

“Our photos and fingerprints have been sent to all the factories, so we are not able to find jobs anywhere else. Blacklists are hanging in front of the factories,” she said.

Mar 1, 2019

Some 750 palm workers at Colombia’s largest plantation yesterday signed a landmark agreement with their employer, Indupalma, culminating a years-long effort in which many workers risked their lives to achieve decent wages and safe working conditions. The workers formed a union and fought to force the company to sign a formalization accord and negotiate a collective bargaining agreement.

Jorge Castillo, SINTRAINAGRO president, Indupalma management and Colombia’s vice minister of labor sign a landmark contract with far-reaching rights for palm workers. Credit: SINTRAINAGRO

The subcontracted workers—who labor for below-poverty wages and are not covered by the country’s labor laws—will now become permanent employees, with health coverage and union representation. They will no longer be required to pay for their own tools, oxen and other animal care or transport—expenses that often left them in debt to their employer. The contract doubles or triples their wages, provides compensation for work-related injury and illness and establishes safety and health measures.

In January 2018, the palm workers walked off the Indupalma plantation in San Alberto demanding the employer formalize their jobs, with a vast majority casting their ballots for a strike despite their status as subcontracted or “cooperative workers,” which prohibits collective action.

Palm Workers Risked Their Lives in Decades-Long Struggle for Rights

In the early 2000s, companies converted permanently employed palm workers to “cooperative’ status, requiring them to join and pay dues to phony cooperatives—structures that enable companies to evade legal responsibilities under the labor law. Eventually, only 600 palm workers out of 6,000 in the palm producing region in the center of the country were permanent employees, and workers say when they protested their brutal working conditions, they often were threatened or physically attacked by paramilitary forces.

The strike and subsequent agreement at Indupalma caps efforts by palm workers to achieve rights on the job at plantations across Colombia, a struggle that often met brutal retaliation: Up to 130 union activists were assassinated and members of five union executive committees were forced to flee for their lives five times in the past 25 years.

Joining together in a “Pacto Obrero” (coalition of workers), workers throughout Colombia’s palm sector have organized plantation by plantation since 2013, winning contracts that ensure direct hiring and living wages. With support from palm workers at other plantations, the Indupalma strike became so large that the vice minister of labor helped negotiate a preliminary pact in mid-2018.

Palm Workers Made Gains with Global Support

Throughout, palm workers received support from Colombia’s Central Union of Workers (CUT), the AFL-CIO and Solidarity Center, along with a regional labor rights center (CAL); the National Agroindustrial Union, SINTRAINAGRO; and the Corporation for Justice and Freedom (CJL).

Solidarity Center’s engagement with palm workers is part of its larger program in Colombia that supports worksite and industry-wide organizing, intensive education on labor rights under the legal framework that came out of the Labor Action Plan, and legal support for worker demands for access to justice. The Solidarity Center also helped workers develop connections with local, national and political leaders, including members of the U.S. Congress, with whom their meetings provided important political support for ending violence against palm worker activists.

The AFL-CIO and five Colombian labor organizations raised the issue of abusive subcontracting in a May 2016 trade submission under the U.S.-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement (CTPA) and the U.S. Department of Labor twice reviewed Colombia’s progress in addressing the worker rights violations highlighted in the 2016 U.S. trade submission. In January 2018, the Labor Department’s second review urged the government to “take additional effective measures to combat abusive subcontracting and collective pacts, including improving application of existing laws and adopting and implementing new legal instruments where necessary.”

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue,

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue,