Mar 7, 2019

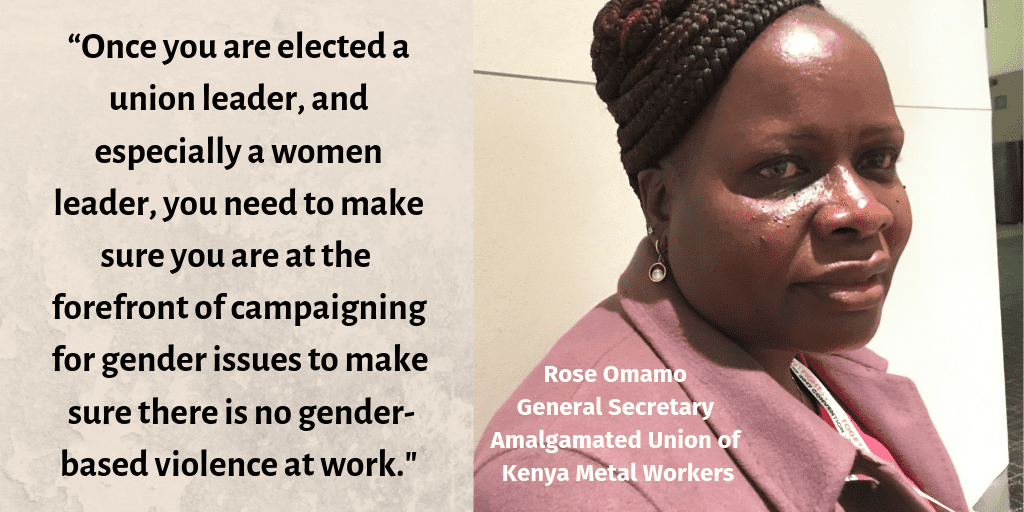

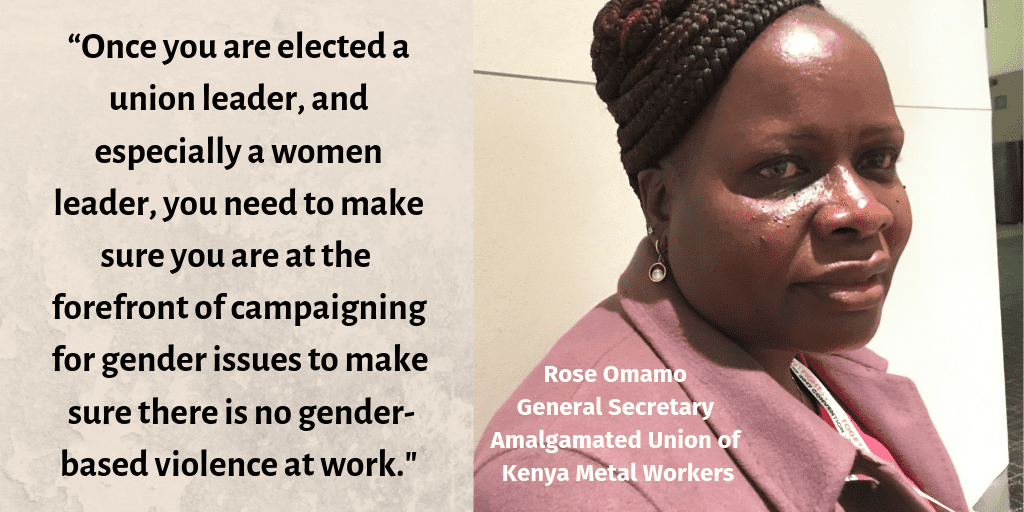

As the international community celebrates March 8, International Women’s Day, Kenya union leader Rose Omamo is meeting with union leaders and government officials across Africa to help propel passage of a proposed global standard that would address gender-based violence at work.

The convention (standard) under consideration by the International Labor Organization (ILO) would end violence and harassment in the workplace. Workers and their unions are championing its adoption with a strong focus on gender-based violence and harassment. Released last week, the most recent draft language of the proposed instrument, “Ending Violence and Harassment in the World of Work” builds on high-level talks in early 2018 among representatives of workers, government and business.

Rose Omamo discussed gender-based violence at work on a Kenya television station in February. Credit: NTV

“We believe we will be able to convince the governments and even some of the employers to support the convention,” says Omamo, general secretary of the Amalgamated Union of Kenya Metal Workers and national Women’s Committee chair of the Congress of Trade Unions–Kenya (COTU-K), a Solidarity Center partner.

In June, representatives of workers, government and business will negotiate final language on a binding convention and recommendation at the International Labor Conference (ILC).

“Our job is to lobby, lobby, lobby and make sure we get support,” says Omamo, who will be among worker representatives at the ILC discussions. She will be joined by union leaders from other Solidarity Center partner unions, including Eulogia Familia, vice president of the Confederación Nacional de Unidad Sindical (National Confederation of Labor UnionUnity, CNUS) from the Dominican Republic, and Fiona Gandiwa Magaya, coordinator of the Zimbabwe Confederation of Trade Unions (ZCTU) Gender Department.

Unions Drive Campaign to End Gender-Based Violence at Work

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue, says Solidarity Center Senior Gender Specialist Robin Runge.

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue, says Solidarity Center Senior Gender Specialist Robin Runge.

Workers and their unions are seeking a definition of violence at work in the final convention that would encompass transportation to and from work, an area in which employer groups are resisting. But Omamo believes it is imperative to include the time in which a worker commutes.

“For example, there was a company where workers reported very early in the morning. When the lady was going to work very early in the morning, when she was just crossing the railroad tracks, she was raped,” says Omamo. “These things are happening to us and are affecting us.”

Other issues include ensuring the final convention encompasses broad definitions of who is covered and what constitutes “violence and harassment.”

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), which has helped coordinate and guide the campaign to end gender-based violence at work, offers information and tools to assist unions and organizations in taking action.

Building Support to End Gender-Based Violence at Work

Omamo and her sisters have been working doggedly over the past year to create awareness of and build support for passage of the convention. Omamo has traveled across Kenya to educate union members, such as engineers in glass, metal and petroleum, about the draft proposal.

As a representative on the gender commission of the Organization of African Trade Union Unity (OATUU), Omamo has met with government officials in Uganda and elsewhere to push for their support of the convention. In April, COTU-Kenya is hosting a meeting of women union unionists from the 18 OATUU member countries who will share input from their discussions with government officials, so the group can determine the level of government support for the convention and identify potential stumbling blocks going into the June ILC meeting.

When meeting individually with government leaders, Omamo says she describes the far-reaching consequences for workers experiencing sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence at work. “Some people even leave jobs because of the kind of harassment they go through at work—not because they don’t want to work, but because the bosses they have are sexually harassing them,” she says.

“Once you are elected a union leader, and especially a women leader, you need to make sure you are at forefront of campaigning for gender issues, make sure there is no gender-based violence at work, and make sure women are working in a safe environment,” says Omamo, who became the first woman to lead her 11,000-member union.

“This is a convention is very close to our hearts.”

Mar 4, 2019

Even as 11,000 Bangladesh garment workers were fired in the wake of strikes they waged in December and January to protest low wages, many seeking to form unions or take collective action also have been physically threatened, attacked and arrested on trumped-up charges. And union leaders say these employer-directed assaults often take the form of gender-based violence at work.

In testimony provided to the Solidarity Center by garment workers and union leaders, a pattern emerges in which women seeking to form unions or engage in collective action are especially targeted with actions to degrade, demean and intimidate them, and some have suffered physical attacks and rape.

“As we try to form unions, management is hostile against us,” says one garment worker. (Neither workers nor factories will be identified to protect workers against retaliation.) “They threaten me that, what if someone stops me in the road, what can I do as a woman?”

Children Injured in Police Attack on Factory

At one factory where workers walked out on January 7 to demand higher wages, police charged them and threw tear gas into the factory, injuring between 13 and 14 children in the ground floor day care. Managers later “sent out a list of all the mothers with babies and terminated them,” says one worker at the factory. “They did this so that they could close down the day care.”

On the same day, at another garment factory where workers say managers had harassed them ever since they submitted a union registration application in November, police beat workers with rods and sticks and “took away the scarves of women,” threatening to rape them, according to a worker’s eyewitness account.

While Bangladesh employers stepped up attacks directed at women workers during the recent walkouts, they have long used gender-based violence at work as a tactic to intimidate women active in union organizing. In November, hired criminals associated with management and local government officials attacked and raped a woman organizer at a factory in the midst of a campaign to form a union.

Crackdown Amplifies Ongoing Assaults on Worker Rights

The harassment, assaults and arrests of garment workers this year amplifies an increasingly repressive environment for worker organizing that in recent years has included threatening home visits, kidnappings and mass termination.

In one recent example, workers at a garment factory saw their daily production quota increased to 400 pieces a day, up from 250 pieces after they filed with the government for union registration. Workers there say supervisors locked union committee members in bathrooms and hired local criminals to pursue them in the streets.

Even as employers exploit workers’ wage protests as a pretext for infringing on the rights of workers to organize and bargain collectively, government resistance to workers seeking to register unions further represses workers’ efforts to form unions and collectively bargain better wages and working conditions.

Following the deaths of more than 1,200 garment workers in the 2012 fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory and the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse, workers vigorously organized to form unions and negotiate contracts, as the Bangladesh government and ready-made garment (RMG) employers responded to international pressure to improve safety and wages.

But now Bangladesh, which in 2018 the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) ranked as among the world’s 10 worst countries for worker rights, is on the verge of expelling the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. Established after the Rana Plaza disaster, the legally binding agreement between hundreds of primarily European retail brands and unions conducted safety inspections at more than 1,000 factories and educated workers on safety and other workplace rights.

And without the freedom to form unions and bargain collectively, internationally recognized rights, Bangladesh garment workers are unable to collectively negotiate safer, healthier workplaces.

“We are poor. Just because we formed a union, we have been the victims,” says one worker at a factory where 200 workers were fired after they sought to register a union with the government. The worker says when management learned of their efforts to form a union, women were threatened with rape and men threatened with guns and knives.

“Our photos and fingerprints have been sent to all the factories, so we are not able to find jobs anywhere else. Blacklists are hanging in front of the factories,” she said.

Feb 26, 2019

Kwasi Adu Amankwah, general secretary of the African Regional Organization of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC-Africa), was forcibly taken from his hotel at 2 a.m. today in Harare, Zimbabwe, where he had just arrived.

Amankwah was set to meet with leaders of the Zimbabwe Trade Union Confederation (ZCTU) when state security agents took him to Robert Mugabe International Airport, where he has been held for hours.

Officials refused to allow a lawyer from ZCTU to see Amankwah at the airport, according to ZCTU.

“It’s a sad development,” ZCTU President Peter Mutasa told the media. “We are in trouble as human rights defenders and trade unionists.”

Other ITUC representatives from Brussels who sought to travel to Zimbabwe with Amankwah were denied visas.

In addition to the solidarity visit to ZCTU, Amankwah was scheduled to meet with the Zimbabwe Ministry of Labor and representatives of the International Labor Organization (ILO) and employers’ federation. Amankwah has not been charged nor informed of the reason for his detention, according to ZCTU.

“It is not clear why such a senior trade union leader was detained at his hotel in the early morning hours and whisked away to the airport without his belongings—and even denied food brought to him by his lawyer and trade union colleagues as he was detained at the airport,” says Solidarity Center Africa Region Director Hanad Mohamud. “This after lawfully entering Zimbabwe. Why is Kwasi being targeted like this?”

In January, after tens of thousands of Zimbabweans protested a 150 percent fuel price hike, ZCTU Secretary General Japhet Moyo and Mutasa were arrested on charges of subversion and beaten in detention. They since have been released but are restricted from travel and must check in with police.

The January crackdown on worker rights’ activists follows the arrest and release of Moyo, Mutasa and 33 other union leaders in October, as government officials attempted to end a nationwide protest against a financial tax increase and rising prices. Some union activists were beaten, ZCTU Harare offices were cordoned off by more than 100 police, and ZCTU leaders not already in jail were forced into hiding.

In a letter to Zimbabwe President Emmerson Mnangagwa, ITUC-Africa asks for Amankwah’s release and “an unreserved apology for this action” from the Zimbabwe Department of Immigration.

The Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) is among unions around the world decrying Amankwah’s detention and likely deportation, condemning the move “in the strongest terms” and demanding his immediate release and freedom to meet with ZCTU and others.

Jan 28, 2019

The global labor community is condemning death threats made against Jean Bonald Golinsky Fatal, president of the Confédération des Travailleurs- euses des Secteurs Public et Privé (CTSP) in Haiti.

Garment union president Jean Bonald Golinsky Fatal is receiving death threats in Haiti. Photo courtesy Fatal

The Confederation of Trade Unions of Workers of the Americas (CSA) and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) are calling on the international community to put pressure on the government to take action to find the perpetrators and bring them to justice.

Fatal’s name reportedly appeared on a list threatening five individuals, one of whom was murdered. Lionel Alain Dougé, executive director of the Tripartite Implementation Commission of the HOPE law, was killed in December at his home in Pétion-Ville, Haiti.

Dougé was responsible for ensuring textile companies adhere to Haitian laws, International Labor Organization labor standards and the HOPE law, which guarantees companies tariff advantages when trading with the United States and European Union.

The CSA and ITUC said in a statement that a joint trade union mission to Haiti in 2018 found rampant anti-unionism which translates into “campaigns of persecution and criminalization of trade union members and leaders.” At least 16 women were beaten by police inside a factory for refusing to return to work in May 2017, according to the ITUC 2018 Global Rights Index, which listed Haiti among countries that systematically violate worker rights.

The challenges to forming unions means workers have little opportunity to improve wages and working conditions. Haiti’s minimum wage is two to three times lower than the cost of living, with a liter of milk costing more than half the daily minimum wage. The resulting extreme poverty is exacerbated by increases in taxes and prices for gasoline, diesel and kerosene.

Jan 22, 2019

Just outside Sri Lanka’s Bandaranaike International Airport, where more than 2 million tourists start their vacations each year, a different reality unfolds in the Katunayake export processing zone (EPZ).

There, thousands of garment workers take their places in factories guarded by electrified fencing to begin long days for little pay, forced to endure grueling production cycles with managers refusing to grant even unpaid sick leave. Sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence are a daily part of the job, they say, often with economic repercussions.

“Women are made to stand and work and when engineers fix machines, they touch the women,” says PK Chamila Thushari, program coordinator for the Dabindu Collective union. “When they complain, engineers don’t fix the machines, which means they can’t meet their quota. The only they way they can earn a good living is to hit the targets set by the bonus,” she says, speaking through a translator.

Garment workers are paid a bare $84 a month—or less, if they are employed outside the EPZs—yet apparel exports generated $4.8 billion for Sri Lanka in 2017, a 3 percent increase compared with the previous year. At 47 percent of total exports in 2016, apparel and textiles are the backbone of the country’s trade.

Yet only 2.8 percent of the revenue comes to the garment workers who cut, sew and package clothes for international brands, says Thushari, and most are malnourished, suffer from anemia, and struggle to feed and educate their children. The cost of living for a family of four—without rent—is $549 a month in urban areas like Colombo, near the Katunayake EPZ.

Workers Fear Reporting Gender-Based Violence at Work

Gender-based violence in garment factories is so common “people have kind of become numb to it.” Credit: Solidarity Center/Sean Stephens

Dabindu (drops of sweat in Sinhalese), launched in 1984 as a local organization to advocate and promote women workers’ rights, transitioned to become a union last year at the request of its members, says Thushari, who has been with the organization for 22 years. In addition to advocating for improved wages, the union is focused on educating women about their rights to a workplace free of gender-based violence.

As is the case at workplaces around the world, Dabindu has found one of the biggest hurdles to addressing sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence is women’s fear of reporting it.

Also, “because this happens so often in garment factories, people have kind of become numb to it,” says Thushari. Dabindu creates awareness programs and trains workers to become leaders on the issue. Because workers are fearful of speaking to employers or the police about abusive incidents, the worker-leaders share their experiences with the union, which takes the information to factory management, multinational brands and others so they may address the problem.

Importantly, it took time for Dabindu to develop trust among the workers so they would feel comfortable sharing their experiences with the union, says Thushari.

Connecting Garment Workers Across the Country

Since the end of the country’s 26-year civil war in 2009, which claimed roughly 100,000 lives, Tamil women, many widowed, have journeyed from the north for employment in garment factories at Katunayake and other southern areas with Sinhala majorities. Many experience difficulties because they do not understand the language, and garment factories often require Tamil women to meet higher targets, says Thushari.

Dabindu is working to foster better understanding between the Sinhala and Tamil garment workers by holding daylong “youth camps,” bringing the women together in a relaxed setting, and also is sponsoring trips for garment workers to war-torn northern Sri Lanka to enable women see the difficult living conditions there that are driving Tamil women to seek employment far from their homes. The union is expanding its program to offer women in the north a chance to travel to the south.

“Sometimes, workers are in tears when they see the difficult living conditions, and that brings them closer to each other,” says Thushari.

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue, says Solidarity Center Senior Gender Specialist Robin Runge.

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue, says Solidarity Center Senior Gender Specialist Robin Runge.