May 16, 2019

Legislation requiring written contracts, paid vacation and annual bonuses for domestic workers passed Mexico’s House and Senate and is expected to be signed into law by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

The landmark law, which also prohibits employers from hiring domestic workers younger than age 15, requires employers provide at least a day-and-a-half off each week and defined rest periods.

The law comes after domestic workers across Mexico began organizing nearly two decades ago to push for their rights on the job, first forming a Support and Training Center for Domestic Workers (CACEH) and in 2015, launching the country’s first domestic workers’ union, SINACTRAHO. Both CACEH and SINACTRAHO are Solidarity Center partners.

“After 18 years of fighting through the Support and Training Center for Domestic Workers and SINACTRAHO, some of our demands are reflected,” SINACTRAHO said Monday in a Tweet after the Senate approved the bill. “We know that we must continue working, but today we are sure that the voice and demands of domestic workers have been heard.”

Domestic workers are rarely covered by countries’ labor laws, with domestic work often viewed as not “real” work. Yet more than 67.1 million domestic workers, predominately women, care for others’ families and homes invisibly and in private, often required to live on the premises of their employer. Away from the public eye, they frequently are subject to abuse.

Domestic Workers’ Global Fight for Decent Work

In Mexico and around the world, domestic workers are joining together to champion their rights to safe work, decent wages and fair treatment on the job. Domestic workers in Mexico took part in the global campaign spearheaded by the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) and the IUF, the global union federation, to successfully push for the 2011 ratification of the International Labor Organization’s historic Convention 189 on domestic workers’ rights. The Domestic Workers Convention went into effect in September 2013 and has been ratified by more than 20 countries.

The obscurity in which domestic workers labor and their daily struggles for respect and fairness were illuminated in this year’s Academy Award-winning film, Roma. The film’s depiction of live-in maid Cleo, working for a family in crisis in turbulent 1970s Mexico City as her own life takes a devastating turn, has widened space for domestic workers to push for their rights and recognition.

Marcelina Bautista, a former domestic worker who founded the Center for Support and Training of Domestic Workers (CACEH) and served as SINACTRAHO co-president, has screened the film widely. She discusses with audiences the real-life challenges Mexican domestic workers confront—and how similar they are to those Cleo faces in the movie.

For Bautista and the 2 million domestic workers across Mexico, the far-reaching legislation defining domestic workers’ rights is a big step after a long struggle.

“We can only hope it will improve the lives of so many women not only on paper but in reality,” Bautista told the New York Times.

May 14, 2019

As a migrant mine worker from Swaziland, Mduduzi Thabethe says he has fewer workplace rights than his South African co-workers. Although all mine workers pay the same amount into the health fund, migrant workers get inferior care and pensions are rare.

“If you are a citizen of South Africa, you see you are building your country and you have something, but we have nothing.”

Although media and policymakers focus on African migrants to Europe, some 80 percent of African migrant workers remain on the continent.

Thabethe’s union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, is among those working to improve conditions for migrant workers.

May 9, 2019

Like women around the world, Indonesian factory, farm and office workers frequently face sexual harassment, bullying, rape and other forms of gender-based violence (GBV) on the job—yet many are unaware that anything can be done to address it.

Now, union women leaders in Indonesia are developing unique strategies to educate and empower working women on their rights to safe workplaces free from gender-based abuse.

“This issue is a big issue but it never has been raised up compared with other issues in the union,” says Sumiyati, chairperson for Women and Children’s Affairs at the National Industrial Workers Union Federation (SPN–NIWUF), a Solidarity Center partner.

“Unions in the past only focused on economic issues—gender-based violence issues have never been our priority in the past”—Nurlatifah, SPN–NIWUF board member. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“Unions in the past only focused on economic issues—gender-based violence issues have never been our priority in the past,” agrees Nurlatifah, SPN–NIWUF board member.

Sumiyati and Nurlatifah, with support from their union, are spearheading the launch of a six-month pilot project, “Free GBV Zone,” at factories where SPN-NIWUF local unions and employers agree to participate.

At least two factory unions in Jakarta have signed up so far, says Sumiyati, speaking through a translator. Training workers will be a key part of the process, which also involves mapping out the type and amount of gender-based violence at the worksite and working with the union and employer on implementing recommendations to prevent GBV. Essential to the project’s success is setting up a monitoring system to assess the implementation of the recommendations.

Documenting Gender-Based Violence at Work

A 2017 survey by the Indonesian women’s rights organization, Perempuan Mahardika, revealed that 56.5 percent of the 773 women garment workers in a Jakarta industrial complex were sexually harassed.

Yet as elsewhere around the world, comprehensive data is not available on gender-based violence in Indonesian workplaces. Following two Solidarity Center trainings in 2018 in which women garment workers in Yogykarta and Samarang explored the root causes of gender-based violence and discussed the gender-based violence they experienced and witnessed in the factories, the women devised a survey to determine the extent of GBV in the world of work.

The five month in-depth research project project among 105 women factory workers found that of those who had been subject to gender-based violence, 71 percent had experienced it at work. After analyzing the results, project leaders crafted a report they will share with the International Labor Organization (ILO) as well as with unions throughout Indonesia. Now, says Nurlatifah, “the union tries to mainstream this issue into every activity the union conducts.”

The report finds that “fueling gender-based violence in the world of work is a lack of understanding about GBV, few or no regulations protecting female workers from violence and little awareness about violence in world of work by employers, the government and workers.”

‘So Much Violence’

Rita Shalya, KSPI secretary-general, conducts trainings for women workers to ensure they know their rights to a violence-free workplace. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

For unions, changing those dynamics starts with awareness training for workers.

“Sometimes women do not understand about gender-based violence,” says Rita Shalya, secretary-general of the Confederation of Indonesian Worker’s Union (KSPI). “Step by step, we try to make them open their eyes about gender-based violence,” she says.

Shalya, who also is vice president of the Pharmaceutical and Health Workers Union (PHWU), has engaged with nurses and other union members in education trainings and follow up through WhatsApp groups to raise awareness of the issue with the ultimate goal of ending gender-based violence at hospitals and health care facilities.

“When I was working in hospital, there was so much violence coming from doctors and coworkers, and also patients,” says Shalya, who experienced such abuse first hand. “It’s very risky in the hospital.”

As a new hospital staff member years ago, Shalya was among six co-founders of a union. Now, she is bringing her deep sense of social justice to focus on ending gender-based violence at work and has an ambitious plan to set up a counseling center for union members experiencing sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence on the job. The center will be staffed with union volunteers, all of whom will be trained by the global union Public Services International (PSI).

Shalya has another goal as well: “Women matters are not a big focus of unions, and so I am trying to put it on the agenda.”

Championing an ILO Convention on Gender-Based Violence at Work

Unions in Indonesia also are working broadly at the international and national levels. SPN–NIWUF partners with some 50 organizations and unions in a nationwide campaign seeking government support for an ILO convention (regulation) on gender-based violence at work.

The convention, championed for years by unions and their allies worldwide, including the Solidarity Center, would address violence and harassment at work. In June, workers, employers and governments will negotiate final language on a binding convention and recommendation at the International Labor Conference.

In Indonesia, Parliament “is actively supporting a campaign on gender-based violence because of the work the campaign has done to build consciousness,” says Izzah Inzamliyah, Solidarity Center program officer in Indonesia. The Draft Law on the Elimination of Sexual Violence has drawn a sharp backlash from conservative forces who say it puts too much emphasis on women’s rights, violates religious values and promotes sex outside marriage.

Meanwhile, Indonesia’s official Commission on Violence against Women reports that there are hundreds of discriminatory national and local regulations targeting women.

For unions, addressing gender-based violence at work is “important for creating a working environment free from gender-based violence for our members,” says Sumiyati. A lawyer by training, she worked for years in the color laboratory of a textile plant, where many women discussed with her incidents of abuse at work.

And when women experience safe workplaces, they also will be more likely to become involved in their unions and communities. Sumiyati cites one shoe factory where the majority of its 52,000 workers are women—yet women’s leadership in the factory union is only 16 percent.

“It’s important [for women workers] to understand about gender-based violence so they will be comfortable conducting their activities so they can be safe and be active in taking part in union leadership and the process of making decisions,” she says.

Apr 23, 2019

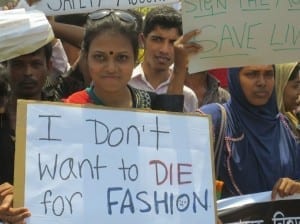

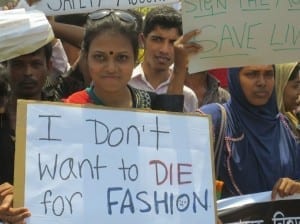

Six years ago, the preventable Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh killed 1,134 garment workers in the world’s worst garment industry disaster. Corporate greed, inadequate labor and building code enforcement, and worker exploitation all contributed to the April 24, 2013, tragedy, which spurred efforts to improve factory safety and support workers seeking a voice on the job.

Nurunnahar mourns the loss of her daughter who died in the Rana Plaza collapse. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Many survivors still face unemployment and poverty because they are too injured to work, according to an Action Aid survey. Months before Rana Plaza collapsed, a fire at Tazreen Fashions factory killed more than 112 workers, part of a pattern of dangerous conditions and deadly risks garments workers face each day in Bangladesh.

Following Rana Plaza, Bangladesh has seen important international and domestic efforts to address fire and building structure risks and improve the labor conditions that hinder workers from reporting dangerous working conditions and violations, and exercising their labor rights. Initiatives like the Bangladesh Accord for Fire and Building Safety, a binding agreement involving fashion brands, unions and the government that helped make many garment factories safer, fueled a rise in union organizing.

And through worker education, like the Solidarity Center’s Fire and Building Safety program, garment workers are boosting their capacity to identify safety and health problems at the workplace and learn about their right to join together to ensure safe workplaces by taking collective action to resolve problems.

6,000 Garment Workers in Solidarity Center Fire Safety Trainings

More than 6,000 Bangladesh garment workers have participated in Solidarity Center safety programs in recent years, including Shilpi Akter, who has worked in the garment industry for more than 10 years.

Some 6,000 Bangladesh garment workers have taken part in Solidarity Center fire safety trainings. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

“Before the Rana Plaza incident, there were no sprinklers, fire doors or emergency lights in our factory,” she says. “I had no idea what fire or health and safety at work meant, neither did we have any trade unions or safety committees.

“Through Solidarity Center’s fire safety training, I learned how to use a fire extinguisher, how to be safe from the fumes during a fire accident, and that I must not keep the clothes I stitch near the heated motor of the machine. This knowledge was unknown to me even a few years back.”

Bilkis Begum, a garment worker and a union president, says before Rana Plaza, “we handled the toxic chemicals without any precaution and had no idea on what to do in case of a fire accident except to run.”

Mohammed Ronju paints the incident more starkly. “There would be no Rana Plaza if it had a union,”’ says Ronju, who has worked in the garment industry for 15 years. If workers had a union, they “would not go inside the building when they sensed trouble. They would have strongly resisted the pressure from management to go inside a building about to collapse.” The day before the Rana Plaza disaster, building engineers declared the structure unsafe. Yet managers threatened to withhold wages if workers did not show up for work the day Rana Plaza collapsed.

‘No More Rana Plazas’

Each year, tens of thousands of Bangladesh workers rally on the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster to demand safe working conditions. Photo: Solidarity Center/Sifat Sharmin Amita

The Rana Plaza tragedy prompted international efforts, through the Accord and other mechanisms, to ensure dangerous garment factories were closed or repaired and safety measures instituted. As a result, factory compliance with fire and building safety codes has improved. Yet much more work remains to be done to ensure full compliance with basic fire and building safety and occupational health standards, and to guarantee enforcement of fundamental labor laws, including workers’ right to form unions.

Since November 2012, at least 1,304 Bangladesh garment workers have been killed and at least 3,877 injured in factory fires and other workplace incidents, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center.

All the more reason, experts say, the Bangladesh government must not roll back international safety inspections.

Says Bilkis Begum: “Surely, we all would agree that it should never be the case that we could sacrifice another Rana Plaza to complete the remaining task of making the workplace safe for the garment workers of Bangladesh.”