Feb 21, 2020

A leader of Colombia’s national petroleum union barely escaped with his life following an early-morning assassination attempt Monday.

The attack on Jonathan Urbano Higuera, president of the USO local for Puerto Gaitán, in Meta Department, occurred as he traveled in a vehicle assigned by the National Protection Unit, a government entity that assigns protection to endangered social leaders.

The USO reports that two armed men on motorcycles approached the vehicle and fired. Bullets shattered the rear window, and it was the quick thinking of the driver who saved lives and prevented injuries.

Urbano Higuera and four other USO leaders in Puerto Gaitán all have received harassing phone calls and death threats this year—as have fellow leaders from across Colombia, including in Huila, Magdalena Medio, Putumayo, Tolima and the capital, Bogotá.

In a statement, the union is calling on authorities to full investigate this incident and all threats against union leaders, as well as to guarantee that their ability to exercise union rights be protected. The USO is a Solidarity Center partner. In early February, the Colombian Workers Federation denounced acts of intimidation and overt threats—including a flier distributed by the Black Eagles, a far-right paramilitary group—to union leaders, members of the National Strike Committee and other social leaders.

Meanwhile, Colombian teachers are in the streets today in a “Strike for Our Lives,” to denounce the murders of and threats to social justice, rights activists and community leaders.

Within the first 52 days of this year, 51 Colombian social leaders—including union leaders and worker rights advocates—have been murdered.

Feb 10, 2020

In Bangladesh, garment workers often seek to form unions and worker associations to better protect against wage theft, unfair treatment and lack of health and safety protections, including large-scale safety threats like building collapses. Yet they increasingly are being denied the ability to do so because of an intensifying anti-worker environment in which their efforts to form unions are suppressed. Even when they succeed in forming unions, their attempts to register them with the government often are denied, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center.

Golam Azam, a BGIWF organizer, says garment workers encounter government resistance when registering unions. Credit: Solidarity Center/Istiak Inam

Of the 1,031 union registration applications tracked between 2010 to 2018, the government rejected 46 percent—even though registration is meant to be a simple administrative process. Union leaders say the Registrar of Trade Unions (RTU) imposes burdensome conditions and rejects applications for reasons like lack of a union members’ ID or other employer-provided documents (which is not required by law), or because the factory ID number does not match with factory records (even though it is up to management to provide correct ID numbers).

Meanwhile, unions are rarely provided an opportunity to rebut the RTU determination.

Golam Azam, an organizer with the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF), has firsthand experience with such rejections.

“We have submitted trade union registration forms for Moon Radiance Ltd., with 2,000 workers in that factory, three times since 2018 and have been rejected each time,” he says. “For FGS Denimware Ltd., we have submitted the forms twice but got rejected. We were going to submit it the third time, but management made their own union right before we submitted the form.”

Unions, Workers Targeted for Standing Up for Their Rights

Bangladesh’s ready-made garment (RMG) sector employs nearly 4 million workers and increased its annual revenue from $19 billion to $34 billion between 2012 and 2019—a 79 percent rise. Yet, workers continue to earn the lowest wages in the region, even after a wage increase at the end of 2018 made the legal monthly minimum wage $95—roughly half of the wage needed to make ends meet in Dhaka, the capital, where the cost of living is equivalent to that of Montreal.

Outraged that the new minimum wage did not reflect the amount needed to get by, garment workers protested in December 2018 and January 2019. More than 11,000 union leaders and garment workers were fired following the demonstrations, and blacklists bearing workers’ names and faces hung outside factory gates. Dozens of workers were arrested, and some remained in jail on trumped-up charges for more than a month.

Outraged that the new minimum wage did not reflect the amount needed to get by, garment workers protested in December 2018 and January 2019. More than 11,000 union leaders and garment workers were fired following the demonstrations, and blacklists bearing workers’ names and faces hung outside factory gates. Dozens of workers were arrested, and some remained in jail on trumped-up charges for more than a month.

Following the crackdown on workers, fewer garment workers sought to form or register unions. Unions filed only eight registration applications from December 2018 to January 2019 compared with 33 from December 2017 to January 2018, according to Solidarity Center data.

Union supporters experience constant employer harassment and intimidation, including dismissals for union activism, as well as verbal and physical abuse by management.

“Management puts extra workload on the union leaders and in many cases terminates the workers who they think might protest in future,” says Azam. “For instance, in Al Gawsia factory in Ashulia, false cases have been filed against union leaders and members so that they can be terminated and will not get their due benefits. Workers are subject to false cases even when they do nothing against the law, but when the management violates the law, they are not subject to any repercussion.”

‘A Union Has Empowered Me to Demand My Rights’

Following the deaths of more than 1,200 garment workers in the 2012 fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory and the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse, workers vigorously organized to form unions and negotiate contracts, as the Bangladesh government and RMG employers responded to international pressure to improve safety and wages.

Yet for many workers at the country’s 5,000 garment factories, fire safety and other hazards are still a danger, and employers often arbitrarily fire workers, deny them maternity leave or other legal benefits, and sexually harass women workers or engage in other forms of gender-based violence—making the ability of workers to form unions and worker associations essential.

Mosammat Shorifunnesa, a garment worker and factory union leader, describes how the union made a difference for his co-workers.

“In one instance, five of my workmates were ordered to stay after work and were then fired the same day without prior notice or any payments,” she says. After multiple meetings with management, the factory compensated each worker between $766 and $1,120, as required by Bangladesh Labor Act.

“The trade union is not just an organization, it is a bond between the deprived and the voiceless that enables us to have collective power,” says Shorifunnesa. “It has empowered me to demand my rights and has united my workmates. It gives me the strength to stand by them, and them the courage to stand by me.”

Feb 7, 2020

Taxi drivers in Ghana, tortilla vendors in Honduras and Asian domestic workers in countries across the Gulf region—all are part of the world’s informal economy, comprising 2 billion workers or 61 percent of the global workforce.

Although informal economy workers create more than one-third of the world’s gross national product, most are either not covered or insufficiently covered by laws or working arrangements guaranteed to formal workers, and have little power to advocate for living wages and safe and secure work.

Although informal economy workers create more than one-third of the world’s gross national product, most are either not covered or insufficiently covered by laws or working arrangements guaranteed to formal workers, and have little power to advocate for living wages and safe and secure work.

But by joining in unions or other worker associations, workers in the informal economy can gain the collective power they need to make change, according to a new International Labor Organization (ILO) study.

“Interactions Between Workers’ Organizations and Workers in the Informal Economy: A Compendium of Practice,” highlights 31 examples of how unions around the world have reached out to workers in the informal economy, improved their working conditions, and supported their transition into the formal economy.

“Most people enter the informal economy not by choice but as a consequence of a lack of opportunities in the formal economy and the absence of other means of livelihood,” according to the ILO’s 2015 Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy Recommendation (No. 204). “The transition to formality is essential for inclusive development and decent work for all.”

Collective Power for 100,000 Zimbabwe Informal Economy Workers

The vast majority of workers in Africa, nearly 86 percent, depend on the informal economy to make a living.

While globally, more men (63 percent) than women (58 percent) work in informal employment, in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, the reverse is true. In Africa, nearly 90 percent of employed women are in informal employment compared to 82 percent of men. Women working in the informal economy are often in more vulnerable situations than their male counterparts, for example, as domestic workers who labor in private homes away from the public.

In Zimbabwe, where the proportion of informal employment is more than 94 percent of total employment (including agriculture), the Compendium of Practice explores how the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU), undertook a pathbreaking partnership with informal economy workers to advocate for legal changes that would improve their working conditions and livelihoods.

In 2002, ZCTU, a Solidarity Center partner, joined with the Employers Confederation of Zimbabwe and the Ministry of Labor to form the Zimbabwe Chamber of Informal Economy Associations (ZCIEA). The association now has 30 territories, each with between five and 10 chapters of 500 informal economy members each. As of 2019, there were 100,000 members in 150 associations.

Market Vendors Harassed, Bullied by Authorities

One of the key challenges informal economy workers face in Zimbabwe is harassment and criminalization of the informal economy. Most informal workers often lack the required licenses to operate, which often cost more than they can pay or only can be procured in cities hundreds of miles from where they live.

As a result, informal workers report widespread harassment and bullying by authorities. In a 2016 ZCIEA survey, 81 percent of 514 informal workers said they have been bullied, with 22 percent specifying that the harassment involved both confiscation of goods and threats of violence. Some 36 percent noted the source of harassment stemmed both from the local authorities and the Zimbabwe Republic Police, the national police force of Zimbabwe.

In highlighting the Zimbabwe example among its case studies, the Compendium of Practice points to how ZCIEA has negotiated for and come into agreement with various local government authorities on new approaches, such as reviewing laws to regularize informal workers.

“ZCIEA has increased the engagement of informal economy workers in policy discussions,” according to the study.

Working with partners like ZCTU throughout the world, Solidarity Center provides trainings and programs to help informal economy workers better understand their rights, organize unions to mitigate job vulnerabilities, and learn to bargain for improved conditions and wages. We connect workers with unions, legal services and pro-worker organizations to challenge exploitation.

Jan 24, 2020

Imagine the population of New York City. Then triple that number. That’s how many people around the world are being robbed of their freedom through human trafficking—24.9 million.

While “trafficking” seems to imply movement across borders, some 77 percent of those targeted by human traffickers do not leave their country of residence, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). Most are trafficked for forced labor, one-third are children.

Solidarity Center’s Neha Misra testified on Capital Hill on the need for worker rights in forming unions and bargaining as key to ending human trafficking. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“Human trafficking thrives in a context of private actors and economic coercion,” says Neha Misra, testifying recently on Capitol Hill before the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission in a House Foreign Relations Committee hearing.

“We must address what one leading global expert on the international law of human trafficking calls the ‘underlying structures that perpetuate and reward exploitation, including a global economy that relies heavily on exploitation of poor people’s labor to maintain growth and a global migration system that entrenches vulnerability and contributes directly to trafficking,’ ” says Misra, Solidarity Center senior specialist for migration and human trafficking. Trafficking and severe labor exploitation are part of a continuum of labor exploitation and abusive working conditions workers face around the world in workplaces as diverse as factories, farms and offices.

The Lantos hearing was part of a series of congressional events in January around U.S. Human Trafficking Awareness Month, which marks the date Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) in 2000. That same year, the United Nations passed the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (the Palermo Protocol). As part of the TVPA, the U.S. State Department each year issues a detailed report on trafficking in persons, ranking countries on the extent to which they are addressing and eliminating it.

Since then, global nations have a clearer understanding of human trafficking—including its direct connection to forced labor and exploitation—and 168 governments have implemented domestic legislation criminalizing all forms of human trafficking, transnationally and nationally.

Yet as indicated by the staggering number of those trafficked, much more needs to be done.

“Over the past 20 years, the extent of forced labor in global supply chains has become increasingly clear. And yet, governments continue to fail to hold corporations to account,” says Misra.

Migrant Workers, Domestic Workers Targets of Trafficking

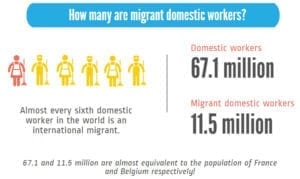

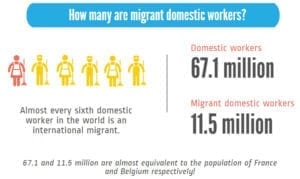

Isolated in private homes, domestic workers, whether nationals or migrants, are particularly at risk of exploitation, harassment and abuse, including sexual violence—and have difficulty accessing justice. Domestic workers, who comprise 11.5 million migrant workers—are also among the largest group of trafficked migrant workers and are vulnerable to human trafficking and forced labor—within their home countries, as internal migrants, and as cross-border migrants.

Isolated in private homes, domestic workers, whether nationals or migrants, are particularly at risk of exploitation, harassment and abuse, including sexual violence—and have difficulty accessing justice. Domestic workers, who comprise 11.5 million migrant workers—are also among the largest group of trafficked migrant workers and are vulnerable to human trafficking and forced labor—within their home countries, as internal migrants, and as cross-border migrants.

“Recognizing domestic workers as workers is key to combatting the vulnerability they face to human trafficking,” says Alexis De Simone, Solidarity Center senior program officer for the Americas. De Simone spoke at a Capitol Hill briefing Friday sponsored by U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal.

A domestic worker who requested anonymity described at the briefing the abusive conditions she experienced after a diplomat brought her from Chile to the United States in 2009. She was promised fair wages and benefits, but after she started working, the family refused to pay her. Her employers withheld food, stole her passport, and threatened her with deportation if she talked with anyone outside the household—an all-too common experience for domestic workers worldwide.

Collective Action Key to Ending Trafficking, Forced Labor

Combating human trafficking, forced labor and other forms of severe labor exploitation means putting worker rights at the forefront of solutions.

The 2011 ILO convention (global treaty) covering domestic workers “has raised the bar globally for states and employers to recognize and enforce the labor rights of domestic workers,” says De Simone.

Domestic workers around the world educated and mobilized for passage of the ILO Convention on Domestic Workers, along the way helping workers understand that violence, abuse, coercion and intimidation are not part of the job. “And that recognition, that righteous indignation, is often the spark for organizing that helps us end the imbalance of power,” says De Simone.

“Recognizing domestic workers as workers is key to combatting the vulnerability they face to human trafficking”—Alexis De Simone, Solidarity Center. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

Yet not only international law, but on-the-ground grassroots union organizing and building power among domestic workers is key to combating vulnerability to trafficking, she says. “Union contracts are helping domestic workers worldwide ensure their rights to safe jobs without forced labor and human trafficking.”

De Simone cited examples of how union collective bargaining agreements have improved conditions for domestic workers in Argentina, Uruguay and Sao Paulo, Brazil, and shared the success of domestic workers in Mexico who ensured the country’s new labor law includes domestic workers—often among an excluded group of workers in many country’s labor laws.

Unions also are reaching across borders, building union-to-union relationships between countries of origin and destination like Paraguay and Argentina, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, Nepal and Lebanon.

But “freedom of association must be assured in practice, not just law,” says Misra. “This means strict penalties for employers who fire, retaliate against or collude with government officials to deport migrant workers seeking to form unions.”

Says Misra: “From rubber plantations in Liberia, garment factories in Jordan and to domestic workers’ households in Kenya, Solidarity Center has seen time and again how democratic worker organizing and collective bargaining can eliminate forced labor in a workplace.”

Jan 17, 2020

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and the Network Against Anti-Union Violence in Honduras are urging the government to drop all charges against Moisés Sánchez, safeguard his protection as a human rights defender under threat, and ensure he can freely exercise his union activities without violence or reprisal.

Sánchez, secretary general of the melon export branch of the Honduran agricultural workers’ union, Sindicato de Trabajadores de la Agroindustria y Similares (STAS), is on trial January 22 for criminal charges without the right to appeal. He is charged with four counts related to “usurpation” for his community’s construction of an access road and faces a possible 30-year prison sentence.

In the southern community of La Permuta, 450 community members voted in 2018 to build a road allowing residents regular access to nearby towns after government officials documented that the land was publicly owned. Previously, La Permuta residents were unable to cross rivers during heavy rains to Choluteca, where many work in the melon fields.

More than a year after the road was built, a land owner claimed the land as her property and pressed criminal charges. Five elected community leaders have been charged. Sánchez is the only grassroots community member not part of the elected leadership who was charged for the road construction. The Network believes Sánchez is being targeted for his role in seeking decent wages and working conditions for agricultural workers, moves often violently opposed by their multinational employers. The Network fears he would face violence and possible death if imprisoned.

In 2017, Sánchez and his brother, union member Misael Sánchez, were attacked by six men wielding machetes as they left the union office in Choluteca. The company later fired him in what union leaders say is retaliation for his efforts to improve working conditions through a union. Sánchez is among those listed by the International Labor Organization (ILO) as requiring protection from the Honduran government, and as a documented victim of anti-union violence, the Network says that the state has an obligation to protect human rights defenders and should not permit these attacks on their lives and liberty.

Violence Against Union Leaders Frequent Yet Unpunished

The Network’s most recent report on union violence, released in August, finds agricultural worker activists represented three quarters of the victims of anti-union violence in Honduras between February 2018 and February 2019. Yet according to the Network, no arrests were made in 60 cases of anti-union violence in the past three years.

Melon workers on plantations across the Choluteca region have long endured worker rights abuses. After they sought to improve their working conditions by forming unions in 2016 with STAS, a FESTAGRO affiliate, employers intimidated and illegally fired many workers, despite Honduran law and international conventions making it illegal to retaliate against workers for organizing unions to protect their rights on the job.

The ILO held back-to-back hearings at the International Labor Conferences (ILC) in 2018 and 2019 on Honduras’s failure to abide by its international commitments. The ILC report in 2018, which expressed “deep concern at the large number of anti-union crimes, including many murders and death threats, committed since 2010,” urged the Honduran government to protect vulnerable unionists, investigate more than a decade of unsolved murders of union leaders and prosecute those responsible for the crimes.

In 2012, the AFL-CIO and 26 Honduran unions and civil society organizations filed a complaint under the labor chapter of Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). The complaint, filed with the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Trade and Labor Affairs, alleges the Honduran government failed to enforce worker rights under its labor laws. In an October 2018 report, the U.S. Trade and Labor Affairs office said Honduras had made no progress on any of the emblematic cases since 2012.

Outraged that the new minimum wage did not reflect the amount needed to get by, garment workers protested in December 2018 and January 2019. More than 11,000 union leaders and garment workers

Outraged that the new minimum wage did not reflect the amount needed to get by, garment workers protested in December 2018 and January 2019. More than 11,000 union leaders and garment workers

Although informal economy workers create

Although informal economy workers create

Isolated in private homes, domestic workers, whether nationals or migrants,

Isolated in private homes, domestic workers, whether nationals or migrants,