Apr 22, 2015

Rabbi, 10, lost his mother in the Rana Plaza collapse. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

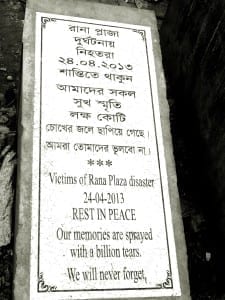

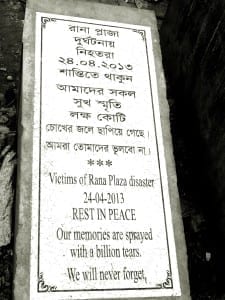

Rabbi Sheikh, 10, began crying when talking about his mother, Shirina Akhter. “I always think about my mother,” he said. Two years ago, Shirina was among more than 1,130 garment workers killed when the multistory Rana Plaza building pancaked. Her husband, Latif Sheikh, heard the building collapse as he sold fruit by the roadside. It took him 17 days to find Shirina’s body.

“My son always cries, remembering his mother,” Latif says. “He is not able to lead a normal life like the others at his age.”

As the global community commemorates the April 24 Rana Plaza tragedy, thousands of garment workers who survived the disaster, mostly young women, remain too injured or ill to work, and the families of those killed struggle emotionally and financially to piece together the lives shattered that day.

Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka recently spoke with survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse, and all say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs.

International labor organizations and prominent retailers created a $30 million compensation fund in 2013 to aid families of workers killed and injured at Rana Plaza. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), 75 percent of those who sought compensation have received something, but to date, 5,000 people have received only 40 percent of the money due them. Further payments have been delayed because clothing brands have failed to pay the $9 million needed to cover claims. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Bangladesh’s $24 billion garment industry is the world’s second largest, after China, and some 80 percent of Bangladesh’s garment exports are destined for the United States and Europe.

Despite constant pain from her injuries at Rana Plaza, Kohinoor, a single mother, is forced to work to support her children. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Kohinoor is among the luckier Rana Plaza survivors. A single mother, she worked as an assistant at Phantom Apparels, one of five factories in the Rana Plaza building. She received some compensation from several sources, including $625 from the ILO and $562 from Primark, which enabled her to pay her medical bills and support her three children for nine months while she was treated for the injuries she sustained.

Despite constant pain, she works as a cleaner in three homes, but her wages are not sufficient to support school fees, and so her children cannot attend school. Her eldest son helps the family by working in a restaurant.

“Nowadays, I have to be absent regularly from my work, as I don’t find the proper strength to work,” she said. Like all those Solidarity Center staff talked with, Kohinoor would like to be fairly compensated so she can support her family.

Standing in the rubble of Rana Plaza, Mosammat Mukti Khatun describes how her injures at Rana Plaza have made it impossible to adequately support her family. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Mosammat Mukti Khatun, 27, was rescued after spending nine hours in the darkness, pinned in the debris of collapsed cement. She also used all of the compensation she received for medical bills and to support her family while she was recovering. Mosammat still suffers from acute pain, and recently suffered additional injuries at a garment factory where she began working in January. Her husband, a day laborer, makes little money, and with five children, the family is in debt.

“I have no money left to secure my days,” Mosammat says. “I do not know how we will get by without additional support.”

On April 24, garment workers and their families plan to form a human chain at the national press club in Dhaka, before placing flowers at the Rana Plaza site.

Apr 21, 2015

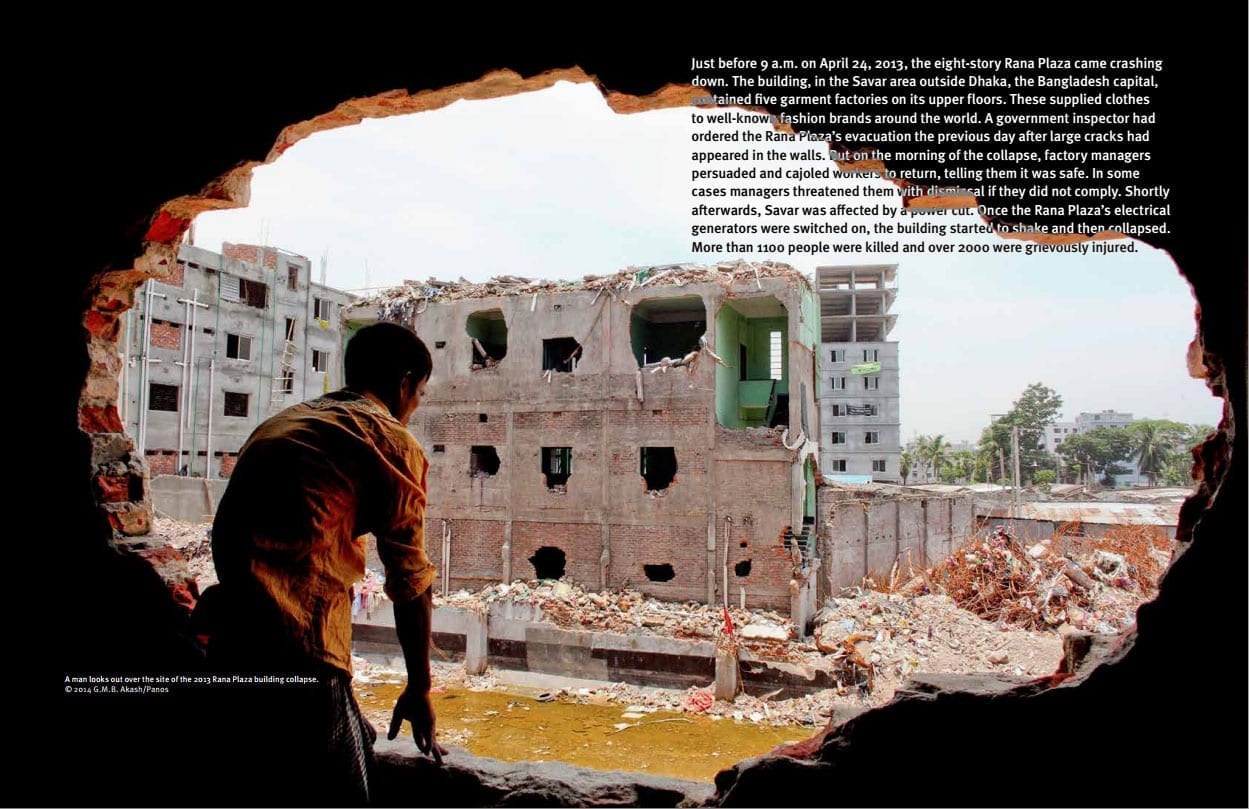

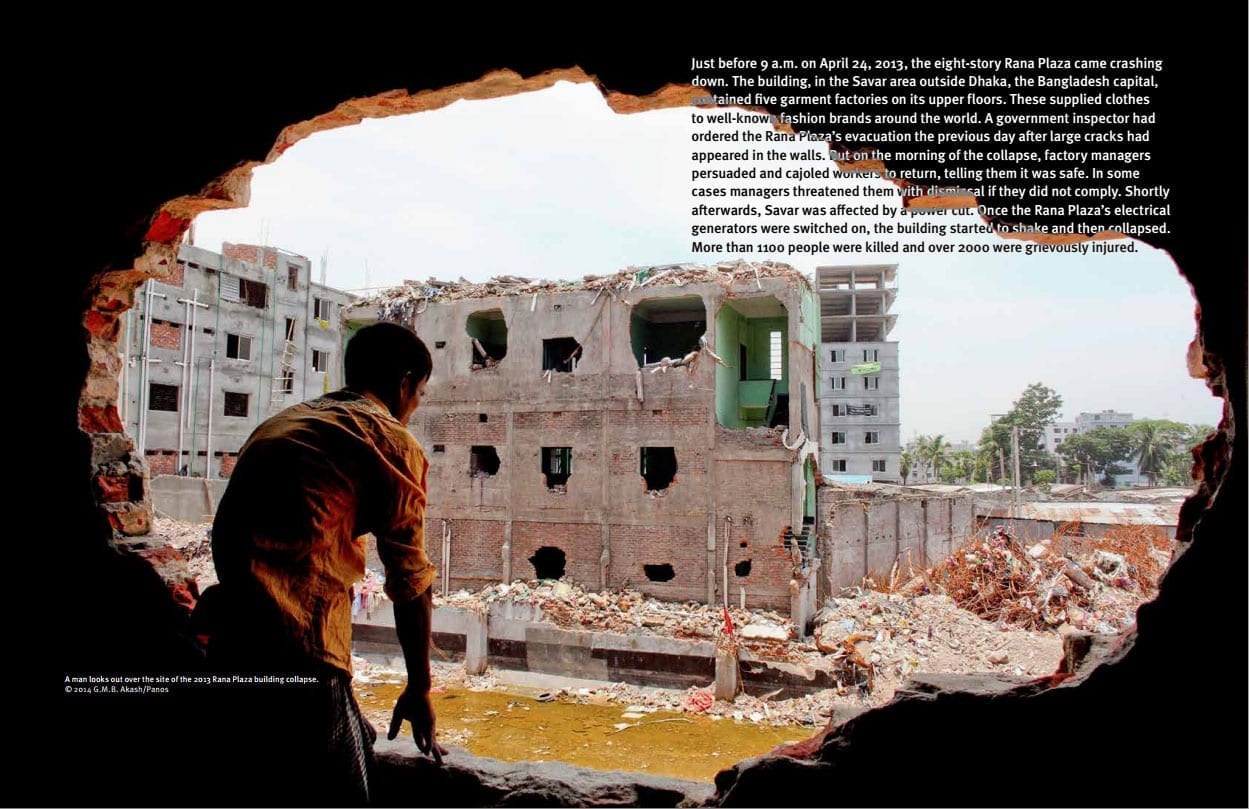

In the initial months after the Rana Plaza collapse on April 24, 2013, a preventable catastrophe that killed more than 1,130 Bangladesh garment workers and injured thousands more, global outrage spurred much-needed changes.

The site of the Rana Plaza building two years after it collapsed. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Dozens of garment factories were closed for safety violations through the Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord process, a legally binding agreement in which nearly 200 corporate clothing brands pay for garment factory inspections. Other inspected factories where problems were identified have addressed pressing safety issues. Workers organized and formed unions to address safety problems and low wages—and the government accepted union registrations with increasing frequency—after the United States suspended its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreement with Bangladesh based upon chronic and severe labor rights violations.

But in recent months, those freedoms are increasingly rare, say garment workers and union leaders.

“After the Rana Plaza and Tazreen disasters, it had become easier to form unions,” says Aleya Akter, president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF). But since November 2014, the government is more frequently rejecting registrations, she said, speaking through a translator while at the Solidarity Center in Washington, D.C., this week. The Tazreen Fashions factory fire five months before the Rana Plaza collapse killed 112 garment workers. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Overall government rejections of unions that applied for registration increased from 19 percent in 2013 to 56 percent so far in 2015, according to data compiled by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital. Despite garment workers’ desire to join a union, they increasingly face barriers to do so, including employer intimidation, threatened or actual physical violence, loss of jobs and government-imposed barriers to registration. Regulators also seem unwilling to penalize employers for unfair labor practices.

“In our view, a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry,” according to a March International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) report. “The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.”

Meanwhile, thousands of workers still toil in unsafe factories. In the two years since the Tazreen fire, at least 31 workers have died in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh, and more than 900 people have been injured (excluding Rana Plaza), according to Solidarity Center data. The Accord and the non-legally binding Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety have nearly completed their inspections, which will total fewer than half of the country’s 5,000 garment factories, including 600 factories that have refused entry to inspectors, according to the International Labor Organization.

In recent months, the Solidarity Center has conducted a series of fire safety trainings for garment workers near Dhaka and Chittagong, where most garment factories are located. The 10-day trainings provide workers with hands-on fire and building safety experience.

Following one recent training, Lima, a factory-level union leader, says she “learned a lot.

“We organized our union in mid–2014. The staircase that workers use in my factory used to be blocked and was a fire hazard. But through our union we took the initiative to talk to management about the problem and now the staircase is clear.”

When garment workers like Lima are allowed to form unions, they have the opportunity to create positive changes at their workplaces, making unions fundamental to substantive improvements in Bangladesh garment factories—an opportunity fewer and fewer garment workers can grasp in the current environment.

Apr 20, 2015

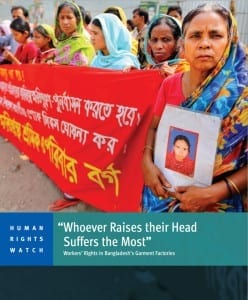

Bangladesh garment workers often risk their health and their lives at unsafe factories, and when they seek to form unions to address workplace problems, “factory managers continue to use threats, violent attacks and involuntary dismissals in efforts to stop unions from being registered,” according to a Human Rights Watch report released today.

“I was beaten with metal curtain rods in February when I was pregnant,” one garment worker told HRW. “They wanted to force me to sign on a blank piece of paper, and when I refused, that was when they started beating me. They were threatening me, saying, ‘You need to stop doing the union activities in the factory, why did you try and form the union.’”

Her experience was not unique, according to “Whoever Raises Their Head Suffers the Most: Workers’ Rights in Bangladesh’s Garment Factories.” HRW also has released a video with garment workers describing the attacks they face when they try to form unions.

Two years after the deadly Rana Plaza collapse that killed more than 1,130 garment workers, the report finds that despite international outrage over the series of mass fatalities at Bangladesh garment factories in recent years, garment workers take great personal risk when trying to improve workplace conditions.

In providing an in-depth look at the experiences of more than 160 workers from 44 factories, the report concludes that “the primary responsibility for protecting the rights of workers rests with the Bangladesh government.

“The poor and abusive working conditions in Bangladesh’s garment factories are not simply the work of a few rogue factory owners willing to break the law. They are the product of continuing government failures to enforce labor rights, hold violators accountable and ensure that affected workers have access to appropriate remedies.”

Rigorous enforcement of existing law would go a long way toward ending impunity for employers who harass and intimidate both workers and local trade unionists seeking to exercise their right to organize and collectively bargain, according to the report.

“If Bangladesh wants to avoid another Rana Plaza disaster, it needs to effectively enforce its labor law and ensure that garment workers enjoy the right to voice their concerns about safety and working conditions without fear of retaliation or dismissal,” says Phil Robertson, HRW’s Asia deputy director.

The report also notes the lack of full financing for the Rana Plaza compensation fund, stating that it “should not be seen as a success or a model unless and until it is replenished and full compensation is paid to claimants.”

Among the report’s recommendations:

- The Bangladesh government should carry out effective and impartial investigations into all workers’ allegations of mistreatment, including beatings, threats and other abuses, and prosecute those responsible.

- The Bangladesh government should revise its labor law to ensure it is in line with international labor standards.

- Companies sourcing from Bangladesh factories should institute regular factory inspections to ensure that factories comply with companies’ codes of conduct and Bangladesh labor law.

Apr 17, 2015

Some 30 global unions, corporations and nonprofit networks are urging the U.S. State Department to ensure its upcoming Global Trafficking in Persons report accurately reflect the serious, ongoing and government-sponsored forced labor in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

“The Uzbek government continues to operate one of the largest state-orchestrated systems of forced labor in the world,” according to letters sent today by the organizations, which include the Solidarity Center, the AFL-CIO, AFT and the Australian Council of Trade Unions. (Read the letters here and here.)

In Turkmenistan, as in Uzbekistan, the government’s “mass mobilization of citizens to harvest cotton degraded public services, especially schools, which sent their teachers to pick cotton,” according to the organizations. “Some officials also forced civil servants to clean and landscape public spaces and to clean the officials’ homes.”

In its 2014 report, the State Department ranked Uzbekistan as “Tier 3,” a designation that means it does not fully comply with the minimum standards set by the U.S. Trafficking Victims and Protection Act (TVPA) and is not making significant efforts to do so. Turkmenistan was ranked on the Tier 2 Watch List, meaning its government does not fully comply with the TVPA standards but is making significant efforts to become compliant.

The organizations are urging the State Department to maintain Uzbekistan’s Tier 3 status and downgrade Turkmenistan to Tier 3. Key to the Tier 3 designation is the extent to which a country serves as origin, transit or destination for severe forms of trafficking and the extent to which officials or government employees are complicit in severe forms of trafficking.

The Trafficking in Persons report “is an important means to shine light on modern-day slavery and to press governments to do more to eradicate it,” the organizations state. Maintaining the Tier 3 ranking not only accurately reflects the reality on the ground, they say, but will help press the governments to take meaningful steps to end forced labor. The letters were sent to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Ambassador Patricia Butenis, acting director of the State Department’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons.

A report released this month found that extortion and bribery fueled the forced labor behind Uzbekistan’s cotton harvest in autumn 2014, a coerced mass mobilization that took teachers, health care workers and millions of other employees away from their duties for several weeks.

In Turkmenistan, tens of thousands of teachers, doctors and other public employees were forced, under the threat of dismissal, to spend four months in the cotton fields, according to a 2014 report by Alternative Turkmenistan News. “The working and living conditions of the forced laborers were abysmal, with people often having to sleep in the open air, drink ditch water and bathe in irrigation channels.”

The U.S. Trafficking in Persons report, issued annually for the past 14 years, covers 188 countries and was mandated by the 2000 Trafficking Victims and Protection Act. The act sets standards to eliminate trafficking and creates enforcement measures, such as the withholding or withdrawal of U.S. non-humanitarian and non-trade-related assistance for countries with low rankings.

Apr 16, 2015

In the hours and days after the multistory Rana Plaza building collapsed in 2013, killing more than 1,100 garment workers in Bangladesh, Solidarity Center Senior Program Officer Lily Gomes was an ever-present figure in the hospitals, where she went from bed to bed checking on injured workers and offering support. She also visited workers at their homes, to offer assistance and to document details of the world’s deadliest garment factory disaster.

Lily Gomes has conducted hundreds of trainings for Bangladesh garment workers. Credit: Solidarity Center

Providing emergency aid is one of a multitude of duties Gomes has undertaken since joining the Solidarity Center’s Dhaka office in 1996. Trainer, union organizer, curriculum developer, gender specialist and financial program monitor—over the years, Gomes has carried out these roles and many more, earning a doctorate in sociology from Jadavpur University in India along the way. Now, she has a new title: Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy in Washington, D.C.

“This is the time clearly to focus on women garment workers to have them in leading positions,” Gomes says of her plans while in residence. During her five month-long Reagan-Fascell fellowship, she will develop a gender policy guideline for advancing women’s leadership among trade unions within Bangladesh’s ready-made garment (RMG) industry. “This is the time for women to express their voices.”

She brings to the fellowship a rare range and depth of experience. Gomes was among Solidarity Center staff aiding garment workers forming their first women-led union in 1996. “I was with them day and night,” she says, recounting the long hours involved in creating the Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation (BIGUF), a milestone achievement not only for worker rights but one that “initiated the idea that women should be the main leadership to reflect the workers in the RMG industry in Bangladesh.”

Lily Gomes (front, left) and Bangladesh garment workers met with then-U.S. Rep. George Miller in 2013 about factory working conditions. Credit: Solidarity Center

In those years, child labor was rampant, and Gomes describes how factory owners would hide children in boxes or even toilets when inspectors arrived. Passage of the Child Labor Deterrence Act of 1999, long championed by former Sen. Tom Harkin, “was a huge thing for Bangladesh that assisted in complete elimination of child labor from the sector at the time,” Gomes says. The bill bans the importation to the United States of products that are manufactured or mined with child labor.

Following the law’s passage, Gomes helped the Solidarity Center set up and run schools for former child laborers “with a unique curriculum to address their needs,” a project that continued through 2002.

“The children were happy,” Gomes recalls. “They started relaxing. They learned not only academics but social issues,” including health and hygiene.

Gomes was coordinator of Solidarity Center-sponsored health clinics offering primary medical care for garment workers and their families. Over the years, she has provided workers with training sessions on topics as varied as labor law, financial management and collective bargaining negotiations. She also conducts fire safety training, a program the Solidarity Center pioneered for garment factory workers in 2000. In addition to helping garment workers unionize, she has assisted shrimp workers to organize and exercise their rights in seafood processing factories in southwestern Bangladesh.

Now, much of her focus is on empowering women garment workers to take on leadership roles and understand their rights to better advocate for themselves and their families. Although women comprise more than 90 percent of garment factory workers, during negotiations at unionized plants, “Women’s issues are sidelined in negotiations,” Gomes says.

“For instance, like ensuring contract language that includes breaks for breast-feeding and special care for pregnant women.” Women also have less access to better paying jobs and supervisory positions, outcomes generated by “socially built gender discrimination.”

In 2000, Gomes administered four Solidarity Center-sponsored Working Women Education Centers, where lawyers trained female factory workers on their rights regarding sexual harassment at the workplace, family leave and other issues important to women. Since then, she has reached hundreds of women workers through trainings on women’s labor rights and gender equality.

“Now, many of these Solidarity Center-trained women are leaders of other union federations,” Gomes says. “It’s a great feeling to know I trained them.”

In the late 2000s, she commuted for several years to India’s West Bengal state, to work on her Ph.D., which focused on the impact of employment and earning opportunities on female workers in Bangladesh’s RMG sector.

Beyond her organizational skills, educational background and talent for expertly taking on a broad range of tasks, Gomes brings to her work a compassion and deep understanding of humanity that sets her apart.

Recalling the hours after the Rana Plaza disaster, she describes visiting a school where bodies, nearly all young women, were laid out in row after row.

“I touched their hands and feet,” she said, “and felt like they were my sisters.”