Apr 22, 2015

Rabbi, 10, lost his mother in the Rana Plaza collapse. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Rabbi Sheikh, 10, began crying when talking about his mother, Shirina Akhter. “I always think about my mother,” he said. Two years ago, Shirina was among more than 1,130 garment workers killed when the multistory Rana Plaza building pancaked. Her husband, Latif Sheikh, heard the building collapse as he sold fruit by the roadside. It took him 17 days to find Shirina’s body.

“My son always cries, remembering his mother,” Latif says. “He is not able to lead a normal life like the others at his age.”

As the global community commemorates the April 24 Rana Plaza tragedy, thousands of garment workers who survived the disaster, mostly young women, remain too injured or ill to work, and the families of those killed struggle emotionally and financially to piece together the lives shattered that day.

Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka recently spoke with survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse, and all say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs.

International labor organizations and prominent retailers created a $30 million compensation fund in 2013 to aid families of workers killed and injured at Rana Plaza. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), 75 percent of those who sought compensation have received something, but to date, 5,000 people have received only 40 percent of the money due them. Further payments have been delayed because clothing brands have failed to pay the $9 million needed to cover claims. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Bangladesh’s $24 billion garment industry is the world’s second largest, after China, and some 80 percent of Bangladesh’s garment exports are destined for the United States and Europe.

Despite constant pain from her injuries at Rana Plaza, Kohinoor, a single mother, is forced to work to support her children. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Kohinoor is among the luckier Rana Plaza survivors. A single mother, she worked as an assistant at Phantom Apparels, one of five factories in the Rana Plaza building. She received some compensation from several sources, including $625 from the ILO and $562 from Primark, which enabled her to pay her medical bills and support her three children for nine months while she was treated for the injuries she sustained.

Despite constant pain, she works as a cleaner in three homes, but her wages are not sufficient to support school fees, and so her children cannot attend school. Her eldest son helps the family by working in a restaurant.

“Nowadays, I have to be absent regularly from my work, as I don’t find the proper strength to work,” she said. Like all those Solidarity Center staff talked with, Kohinoor would like to be fairly compensated so she can support her family.

Standing in the rubble of Rana Plaza, Mosammat Mukti Khatun describes how her injures at Rana Plaza have made it impossible to adequately support her family. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Mosammat Mukti Khatun, 27, was rescued after spending nine hours in the darkness, pinned in the debris of collapsed cement. She also used all of the compensation she received for medical bills and to support her family while she was recovering. Mosammat still suffers from acute pain, and recently suffered additional injuries at a garment factory where she began working in January. Her husband, a day laborer, makes little money, and with five children, the family is in debt.

“I have no money left to secure my days,” Mosammat says. “I do not know how we will get by without additional support.”

On April 24, garment workers and their families plan to form a human chain at the national press club in Dhaka, before placing flowers at the Rana Plaza site.

Apr 21, 2015

In the initial months after the Rana Plaza collapse on April 24, 2013, a preventable catastrophe that killed more than 1,130 Bangladesh garment workers and injured thousands more, global outrage spurred much-needed changes.

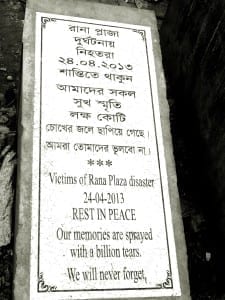

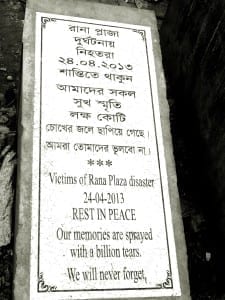

The site of the Rana Plaza building two years after it collapsed. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Dozens of garment factories were closed for safety violations through the Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord process, a legally binding agreement in which nearly 200 corporate clothing brands pay for garment factory inspections. Other inspected factories where problems were identified have addressed pressing safety issues. Workers organized and formed unions to address safety problems and low wages—and the government accepted union registrations with increasing frequency—after the United States suspended its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreement with Bangladesh based upon chronic and severe labor rights violations.

But in recent months, those freedoms are increasingly rare, say garment workers and union leaders.

“After the Rana Plaza and Tazreen disasters, it had become easier to form unions,” says Aleya Akter, president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF). But since November 2014, the government is more frequently rejecting registrations, she said, speaking through a translator while at the Solidarity Center in Washington, D.C., this week. The Tazreen Fashions factory fire five months before the Rana Plaza collapse killed 112 garment workers. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Overall government rejections of unions that applied for registration increased from 19 percent in 2013 to 56 percent so far in 2015, according to data compiled by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital. Despite garment workers’ desire to join a union, they increasingly face barriers to do so, including employer intimidation, threatened or actual physical violence, loss of jobs and government-imposed barriers to registration. Regulators also seem unwilling to penalize employers for unfair labor practices.

“In our view, a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry,” according to a March International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) report. “The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.”

Meanwhile, thousands of workers still toil in unsafe factories. In the two years since the Tazreen fire, at least 31 workers have died in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh, and more than 900 people have been injured (excluding Rana Plaza), according to Solidarity Center data. The Accord and the non-legally binding Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety have nearly completed their inspections, which will total fewer than half of the country’s 5,000 garment factories, including 600 factories that have refused entry to inspectors, according to the International Labor Organization.

In recent months, the Solidarity Center has conducted a series of fire safety trainings for garment workers near Dhaka and Chittagong, where most garment factories are located. The 10-day trainings provide workers with hands-on fire and building safety experience.

Following one recent training, Lima, a factory-level union leader, says she “learned a lot.

“We organized our union in mid–2014. The staircase that workers use in my factory used to be blocked and was a fire hazard. But through our union we took the initiative to talk to management about the problem and now the staircase is clear.”

When garment workers like Lima are allowed to form unions, they have the opportunity to create positive changes at their workplaces, making unions fundamental to substantive improvements in Bangladesh garment factories—an opportunity fewer and fewer garment workers can grasp in the current environment.

Dec 10, 2014

Each year on December 10, the global community marks International Human Rights Day, anchored in the founding document of the United Nations which asserts that each one of us, everywhere, at all times is entitled to the full range of human rights.

That founding document, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, also lists “the right to form and to join trade unions” as a basic tenet of human freedom. For many workers around the world, the right to form unions is essential for ensuring the safe working conditions and living wages that are fundamental to human rights.

Two years ago, on November 24, the devastating fire at the Tazreen Fashion Ltd. garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killed 118 workers, the majority of them young women. Commentators at the time compared the disaster to the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York, noting that moment in American labor history when young women garment workers began organizing their first unions.

The same phenomenon is taking root in Bangladesh, and for the same reasons. The momentum for union formation was accelerated by the April 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh, which killed more than 1,100 workers. Following these twin tragedies, workers, primarily women, formed more than 200 new garment unions. Their rapid formation has been driven by the determination of women workers who have experienced how the past 30 years of job creation has not led to their economic or social advancement. They seized the moment to collectively join together to demand that jobs offer more than a meager paycheck.

It has been a nostrum of development economics for the past 20-plus years that merely creating garment-sector jobs was the key to women’s liberation and empowerment. True, approximately 80 percent of workers employed in the Bangladesh’s garment sector are women. True, millions of women now have an independent means of earning an income, which is important to raising women’s status within their family and community.

However, few adherents to this economic analysis have examined whether creating low-wage jobs has truly led to women’s empowerment in a way that is personal, cultural, sustaining or lasting. Rather, many economists and political scientists view Bangladesh and the global garment supply chain through a purely free-market perspective. Through this lens, any wages at all enable women to improve their status. Yet it is much more difficult to acknowledge that the real issue is the global supply chain within which women need to exert their power and genuinely take control of their own destinies inside and outside the home.

Statistical evidence suggests that women toiling at the bottom of the global garment supply chain in Bangladesh do, in fact, experience some social changes in contrast to women working in a subsistence agrarian economy. Research shows that a 10-hour-a-day, six-days-a-week job in the Bangladesh garment industry may improve women workers’ chances to send their children to school and keep them in there longer. However, these arguments are oversold. Women garment workers may or may not control their wages, depending upon gender-based power relations inside their homes. Often, they do not favor women.

Over the past 17 years that I have been involved with the Bangladesh labor movement, I have repeatedly seen how an income does not guarantee independence for a woman garment worker. This anecdotal evidence is backed up by fact. Research suggests that girls age 17 and 18 years old who live near garment factories actually drop out of school at a higher rate than their rural counterparts who go to work in the industry. Further, a 2009 study by the Bangladesh government’s National Bureau of Economic Research documents that non-garment workers’ mothers had a higher level of education than those of garment workers. And farm labor actually pays more than a job at a garment factory in the high-cost, high-inflation environments of Dhaka or Chittagong, according to a recent article in Dhaka’s Financial Express.

So if the one-dimensional argument that earning a wage results in women’s empowerment is fiction, what is the manifestation of real progress for women?

For the answer, I would point to prominent labor activists who have risen from the factory floors and now are organizing among their peers.

Kalpona Akter, Nazma Akter (no relation) and Nomita Nath, for example, all worked as child laborers in garment factories. They have emerged as real leaders, not because they made poverty wages as teens but because they dedicated their lives to uplifting the status of women workers in their society. They have found their power in fighting for jobs that do not starve, maim or kill women. And they know that vulnerable workers find empowerment when they have a union to represent them.

Workers struggle every day on Bangladesh’s factory floors. Women report that physical and verbal abuse are a matter of course. They are threatened when they do not make a quota or when they get pregnant. Or worse. Mira Boashak, president of a local union in Dhaka, was severely beaten in August by several men who had staked out her garment factory.

Despite these challenges, a young organizer told me earlier this year in Dhaka that prior to recent tragedies, her efforts to organize women into unions made her community think she was a troublemaker. Now, she said, she is seen as a champion of women’s rights and looked up to as a leader.

Real women’s empowerment—realized through asserting fundamental human rights.

Apr 23, 2014

Shumi Akter was not quite 12 years old when she first started working at a garment factory in Bangladesh. By age 18, she had worked as a sewing machine operator at the New Bottom Style garment factory for more than two years, where the $75 a month she was paid helped support her husband and parents, with whom she lived.

On April 24, 2013, Shumi was among the more than 1,100 garment workers who perished in the collapse of the multistory Rana Plaza, which housed five garment factories, including New Bottom Style. Before leaving for work the morning she died, she gave her father more than half a month’s wages so he could pay a debt he owned.

“Now, I cannot find the happiness of life,” says Shumi’s father, Ayub Ali, a rickshaw driver who described his daughter as extremely affectionate.

Shumi’s mother, Amena Begum, still cries at night for her daughter and since the tragedy, has been unable to work at the garment factory where she was employed. Shumi’s body, found 11 days after the collapse, was recognizable only from her identification card and dress.

When Shumi’s parents went to collect their daughter’s body, government officials gave them $244 in compensation. Later, they also received $1,223 from the prime minister’s office and some $300 from private agencies.

Ayub Ali, who makes $3 a day, said “when one of the family member’s income discontinues, then the need is obvious.” Shumi had no children, but two younger siblings remain at home.

“I know very well that even lots of compensation can’t give my daughter back,” Ayub Ali said. “But the compensation can bring little bit of relief towards my family.”

Apr 22, 2014

Rubina and her husband, Abdul Hamid, made enough to support themselves and their two children after they moved five years ago from a village to Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital. Both were employed as garment workers. But their efforts to ensure an even better future for their children ended April 24, 2013.

That day, the multistory Rana Plaza building collapsed, killing more than 1,100 workers, including Abdul Hamid. When Rubina left the factory where she worked to look for her husband in the hours after the disaster, her employer fired her.

Abdul Hamid was killed in the Rana Plaza building collapse. Photo Courtesy Rubina

“I want nobody to become helpless like me,” Rubina said, tears in her eyes. “Me and my husband thought if both of us work hard, we may bring a better future for our children.”

“We once had money. I could feed my children well. They didn’t have to face difficulties. But now I can’t feed them properly, can’t buy clothes for them.” Abdul Hamid, who worked as a cutting master at New Wave Style, one of five garment factories in Rana Plaza, was paid $110 to $122 per month with overtime.

Without a job in a garment factory, Rubina is making $24 a month by cleaning five houses. Her monthly rent, $18, takes up most of her earnings, and she is three months behind in payments. She also must pay for school admission and exam fees.

3, fear that if Rubina returns to work in a garment factory, she, too, will be killed. “They say, ‘Father died, if you go, you will die too. Please don’t go.’ ”

Rubina received $1,223 in compensation from the government—roughly 10 months of her husband’s salary—and another $183 from private organizations, but she will be forced to return to her village if she does not receive sufficient compensation so she can pay her rent and feed her daughters.

The day before Rana Plaza collapsed, engineers identified cracks so serious they said the building should be closed immediately. But many factory managers threatened workers they would be fired if they did not show up for work.

Rubina waited eleven days before some of her husband’s remains were found. She identified him by the pants he wore.

“Hundreds of people lost their lives,” she said. “They (the factory owners) shouldn’t take people’s lives.” She thinks management should get more safety training and the government should inspect the factories to ensure they are safe.

“If (the factory owners) don’t give me compensation, I can do nothing,” Rubina said. The owners, she said, have a responsibility. “My husband died. But his life was valuable.”