Apr 27, 2015

Mércia Silva, director of Brazil’s InPacto, an organization focused on eradicating forced labor in businesses and their supply chains, often must meet with owners and managers of companies where forced labor exists. But she doesn’t approach them “with theory,” she says.

“I take a photograph of a worker working under extremely difficult conditions and I ask them, ‘Would you like someone in your family to work like this?’ ‘Of course not,’ they say, and from there we are able to make change.”

Silva shared her strategies for empowering workers last week on the panel, “Raising the Floor—Fresh Thinking to Improve Working Conditions and Workers’ Rights,” a discussion on worker-driven strategies to improve conditions for workers enduring the most abusive conditions. The panel was part of a two-day, two-city International Labor Organization (ILO) conference, Out of the Shadows: Innovative Approaches to Combating Forced Labor and Other Forms of Worker Exploitation.

“The presence of forced labor in society doesn’t happen in a vacuum,” said Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau. “Forced labor is created by policy. And change comes from the demands and voices of workers and their unions standing up for their rights, standing up for better treatment.” Bader-Blau facilitated the panel, whose primarily U.S.-based participants discussed a range of strategies—including enlisting consumers and the global labor movement—to assist workers in winning their rights on the job.

“You can’t organize anyone with a vague vision,” said Saket Soni, executive director of the National Guestworker Alliance. “These are people who have been staring into the face of evil (forced labor). The alternative has to be concrete. For us, that alternative is, ‘what if you could sit down and negotiate a contract with your employer?’ The only way you can do that is to collectively organize.”

Silva praised Brazil’s Central Union of Workers (Central Unica dos Trabalhadores, CUT) and other Brazil union federations for seeking to make worker rights a reality for agricultural laborers toiling under what she described as “horrible working conditions.

“It’s important to open the door to unions” for these workers, she said. The Solidarity Center works with CUT and other Brazil union federations to help empower vulnerable workers. The AFL-CIO and the CUT have a several decade-long partnership to promote fundamental labor rights in the United States, Brazil and across the Americas.

Women make up a large percentage of workers in forced labor, and panel participants pointed to their key role in taking the lead to improve their working conditions. Neidi Dominguez, director of the AFL-CIO Worker Centers and Community Engagement, discussed how even though Los Angeles carwash workers are predominantly male, women workers were among those who stood up and demanded to be paid a regular wage. Until they did, carwash workers were paid on through pooled customer tips.

The conference, held in in Washington, D.C., on April 22 and in Los Angeles on April 24, brought together representatives from civil society, government and business to discuss strategies to prevent and mitigate exploitative labor practices, with a focus on the United States and Brazil. These strategies aim to decrease workers’ vulnerability to forced labor and other forms of worker exploitation.

“Raising the Floor” panelists also included Steve Hitov, general counsel for the Coalition of Immokalee Workers; and Haeyoung Yoon, deputy program director at the National Employment Law Project.

Apr 22, 2015

Rabbi, 10, lost his mother in the Rana Plaza collapse. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

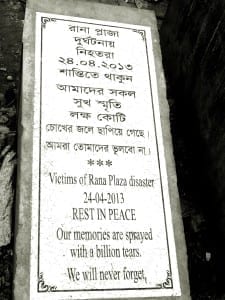

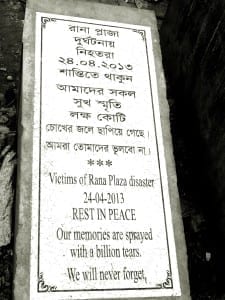

Rabbi Sheikh, 10, began crying when talking about his mother, Shirina Akhter. “I always think about my mother,” he said. Two years ago, Shirina was among more than 1,130 garment workers killed when the multistory Rana Plaza building pancaked. Her husband, Latif Sheikh, heard the building collapse as he sold fruit by the roadside. It took him 17 days to find Shirina’s body.

“My son always cries, remembering his mother,” Latif says. “He is not able to lead a normal life like the others at his age.”

As the global community commemorates the April 24 Rana Plaza tragedy, thousands of garment workers who survived the disaster, mostly young women, remain too injured or ill to work, and the families of those killed struggle emotionally and financially to piece together the lives shattered that day.

Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka recently spoke with survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse, and all say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs.

International labor organizations and prominent retailers created a $30 million compensation fund in 2013 to aid families of workers killed and injured at Rana Plaza. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), 75 percent of those who sought compensation have received something, but to date, 5,000 people have received only 40 percent of the money due them. Further payments have been delayed because clothing brands have failed to pay the $9 million needed to cover claims. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Bangladesh’s $24 billion garment industry is the world’s second largest, after China, and some 80 percent of Bangladesh’s garment exports are destined for the United States and Europe.

Despite constant pain from her injuries at Rana Plaza, Kohinoor, a single mother, is forced to work to support her children. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Kohinoor is among the luckier Rana Plaza survivors. A single mother, she worked as an assistant at Phantom Apparels, one of five factories in the Rana Plaza building. She received some compensation from several sources, including $625 from the ILO and $562 from Primark, which enabled her to pay her medical bills and support her three children for nine months while she was treated for the injuries she sustained.

Despite constant pain, she works as a cleaner in three homes, but her wages are not sufficient to support school fees, and so her children cannot attend school. Her eldest son helps the family by working in a restaurant.

“Nowadays, I have to be absent regularly from my work, as I don’t find the proper strength to work,” she said. Like all those Solidarity Center staff talked with, Kohinoor would like to be fairly compensated so she can support her family.

Standing in the rubble of Rana Plaza, Mosammat Mukti Khatun describes how her injures at Rana Plaza have made it impossible to adequately support her family. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Mosammat Mukti Khatun, 27, was rescued after spending nine hours in the darkness, pinned in the debris of collapsed cement. She also used all of the compensation she received for medical bills and to support her family while she was recovering. Mosammat still suffers from acute pain, and recently suffered additional injuries at a garment factory where she began working in January. Her husband, a day laborer, makes little money, and with five children, the family is in debt.

“I have no money left to secure my days,” Mosammat says. “I do not know how we will get by without additional support.”

On April 24, garment workers and their families plan to form a human chain at the national press club in Dhaka, before placing flowers at the Rana Plaza site.

Apr 21, 2015

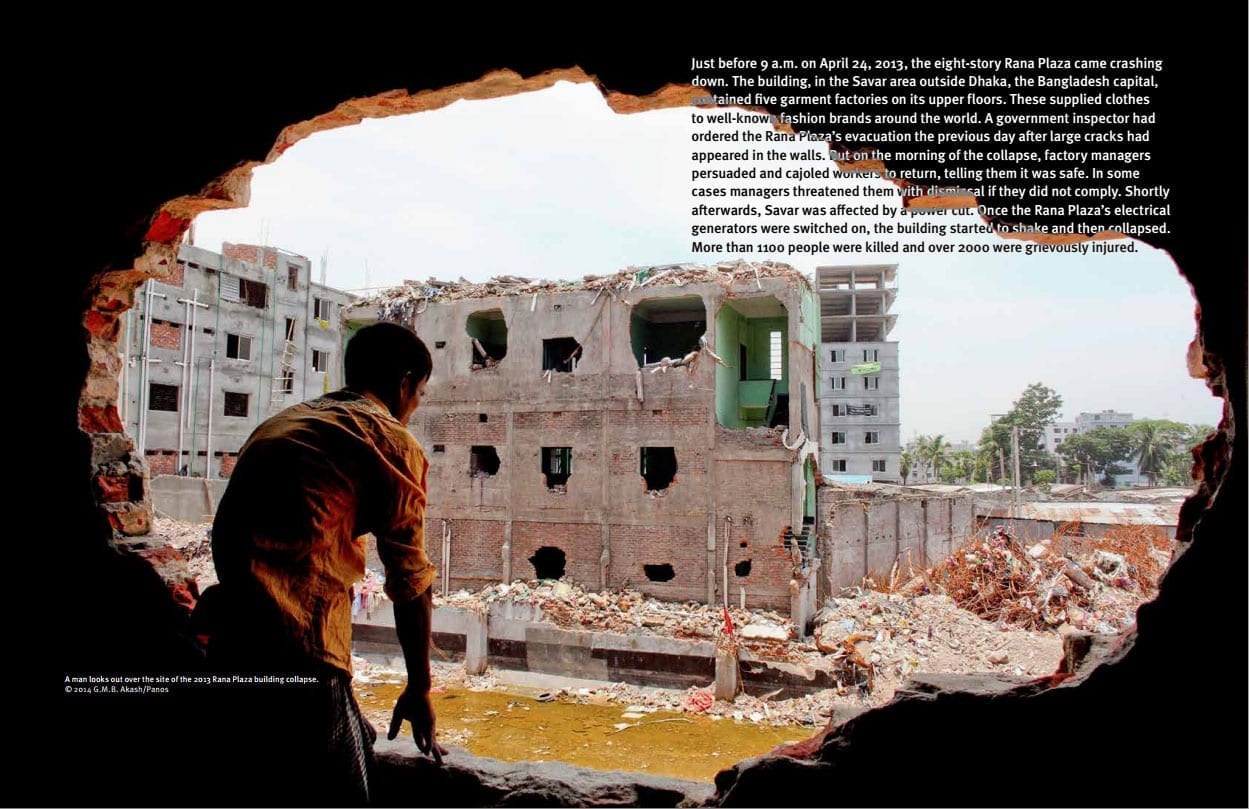

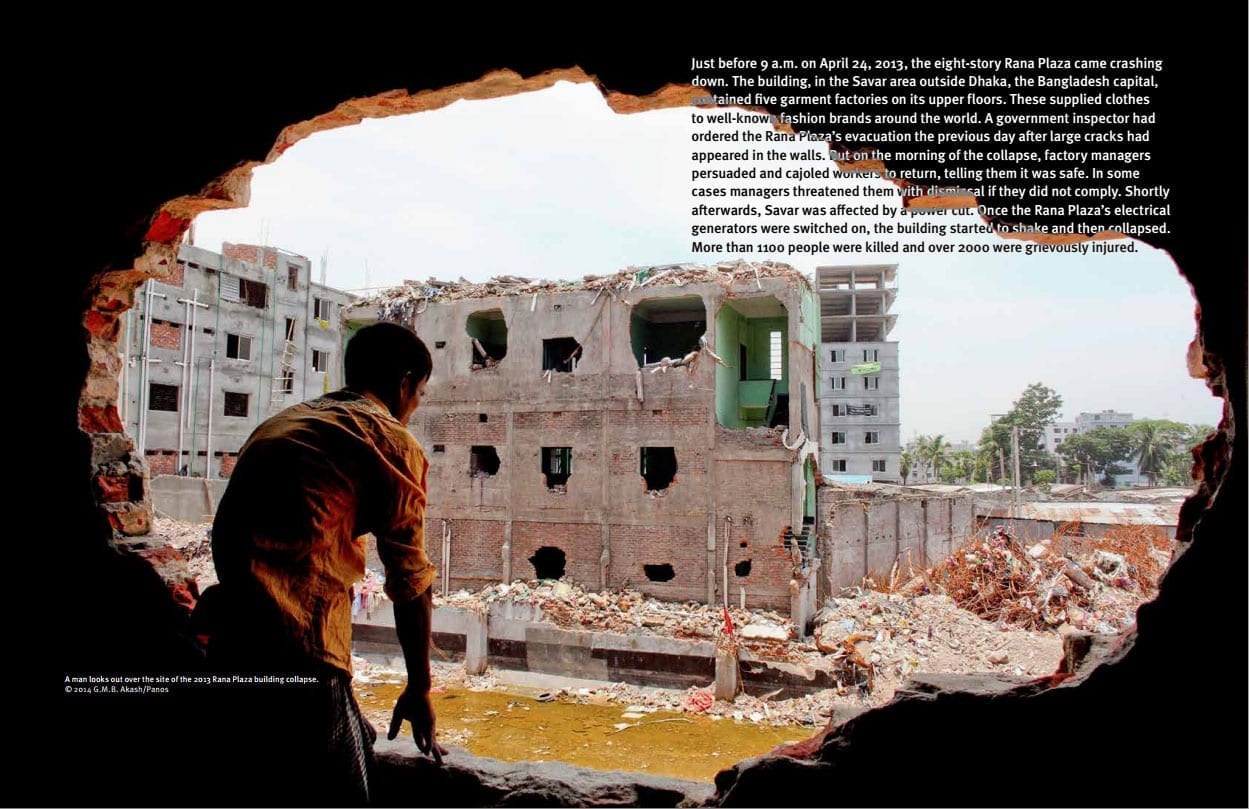

In the initial months after the Rana Plaza collapse on April 24, 2013, a preventable catastrophe that killed more than 1,130 Bangladesh garment workers and injured thousands more, global outrage spurred much-needed changes.

The site of the Rana Plaza building two years after it collapsed. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Dozens of garment factories were closed for safety violations through the Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord process, a legally binding agreement in which nearly 200 corporate clothing brands pay for garment factory inspections. Other inspected factories where problems were identified have addressed pressing safety issues. Workers organized and formed unions to address safety problems and low wages—and the government accepted union registrations with increasing frequency—after the United States suspended its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreement with Bangladesh based upon chronic and severe labor rights violations.

But in recent months, those freedoms are increasingly rare, say garment workers and union leaders.

“After the Rana Plaza and Tazreen disasters, it had become easier to form unions,” says Aleya Akter, president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF). But since November 2014, the government is more frequently rejecting registrations, she said, speaking through a translator while at the Solidarity Center in Washington, D.C., this week. The Tazreen Fashions factory fire five months before the Rana Plaza collapse killed 112 garment workers. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Overall government rejections of unions that applied for registration increased from 19 percent in 2013 to 56 percent so far in 2015, according to data compiled by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital. Despite garment workers’ desire to join a union, they increasingly face barriers to do so, including employer intimidation, threatened or actual physical violence, loss of jobs and government-imposed barriers to registration. Regulators also seem unwilling to penalize employers for unfair labor practices.

“In our view, a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry,” according to a March International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) report. “The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.”

Meanwhile, thousands of workers still toil in unsafe factories. In the two years since the Tazreen fire, at least 31 workers have died in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh, and more than 900 people have been injured (excluding Rana Plaza), according to Solidarity Center data. The Accord and the non-legally binding Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety have nearly completed their inspections, which will total fewer than half of the country’s 5,000 garment factories, including 600 factories that have refused entry to inspectors, according to the International Labor Organization.

In recent months, the Solidarity Center has conducted a series of fire safety trainings for garment workers near Dhaka and Chittagong, where most garment factories are located. The 10-day trainings provide workers with hands-on fire and building safety experience.

Following one recent training, Lima, a factory-level union leader, says she “learned a lot.

“We organized our union in mid–2014. The staircase that workers use in my factory used to be blocked and was a fire hazard. But through our union we took the initiative to talk to management about the problem and now the staircase is clear.”

When garment workers like Lima are allowed to form unions, they have the opportunity to create positive changes at their workplaces, making unions fundamental to substantive improvements in Bangladesh garment factories—an opportunity fewer and fewer garment workers can grasp in the current environment.

Apr 20, 2015

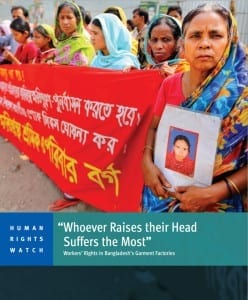

Bangladesh garment workers often risk their health and their lives at unsafe factories, and when they seek to form unions to address workplace problems, “factory managers continue to use threats, violent attacks and involuntary dismissals in efforts to stop unions from being registered,” according to a Human Rights Watch report released today.

“I was beaten with metal curtain rods in February when I was pregnant,” one garment worker told HRW. “They wanted to force me to sign on a blank piece of paper, and when I refused, that was when they started beating me. They were threatening me, saying, ‘You need to stop doing the union activities in the factory, why did you try and form the union.’”

Her experience was not unique, according to “Whoever Raises Their Head Suffers the Most: Workers’ Rights in Bangladesh’s Garment Factories.” HRW also has released a video with garment workers describing the attacks they face when they try to form unions.

Two years after the deadly Rana Plaza collapse that killed more than 1,130 garment workers, the report finds that despite international outrage over the series of mass fatalities at Bangladesh garment factories in recent years, garment workers take great personal risk when trying to improve workplace conditions.

In providing an in-depth look at the experiences of more than 160 workers from 44 factories, the report concludes that “the primary responsibility for protecting the rights of workers rests with the Bangladesh government.

“The poor and abusive working conditions in Bangladesh’s garment factories are not simply the work of a few rogue factory owners willing to break the law. They are the product of continuing government failures to enforce labor rights, hold violators accountable and ensure that affected workers have access to appropriate remedies.”

Rigorous enforcement of existing law would go a long way toward ending impunity for employers who harass and intimidate both workers and local trade unionists seeking to exercise their right to organize and collectively bargain, according to the report.

“If Bangladesh wants to avoid another Rana Plaza disaster, it needs to effectively enforce its labor law and ensure that garment workers enjoy the right to voice their concerns about safety and working conditions without fear of retaliation or dismissal,” says Phil Robertson, HRW’s Asia deputy director.

The report also notes the lack of full financing for the Rana Plaza compensation fund, stating that it “should not be seen as a success or a model unless and until it is replenished and full compensation is paid to claimants.”

Among the report’s recommendations:

- The Bangladesh government should carry out effective and impartial investigations into all workers’ allegations of mistreatment, including beatings, threats and other abuses, and prosecute those responsible.

- The Bangladesh government should revise its labor law to ensure it is in line with international labor standards.

- Companies sourcing from Bangladesh factories should institute regular factory inspections to ensure that factories comply with companies’ codes of conduct and Bangladesh labor law.

Apr 17, 2015

Some 30 global unions, corporations and nonprofit networks are urging the U.S. State Department to ensure its upcoming Global Trafficking in Persons report accurately reflect the serious, ongoing and government-sponsored forced labor in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

“The Uzbek government continues to operate one of the largest state-orchestrated systems of forced labor in the world,” according to letters sent today by the organizations, which include the Solidarity Center, the AFL-CIO, AFT and the Australian Council of Trade Unions. (Read the letters here and here.)

In Turkmenistan, as in Uzbekistan, the government’s “mass mobilization of citizens to harvest cotton degraded public services, especially schools, which sent their teachers to pick cotton,” according to the organizations. “Some officials also forced civil servants to clean and landscape public spaces and to clean the officials’ homes.”

In its 2014 report, the State Department ranked Uzbekistan as “Tier 3,” a designation that means it does not fully comply with the minimum standards set by the U.S. Trafficking Victims and Protection Act (TVPA) and is not making significant efforts to do so. Turkmenistan was ranked on the Tier 2 Watch List, meaning its government does not fully comply with the TVPA standards but is making significant efforts to become compliant.

The organizations are urging the State Department to maintain Uzbekistan’s Tier 3 status and downgrade Turkmenistan to Tier 3. Key to the Tier 3 designation is the extent to which a country serves as origin, transit or destination for severe forms of trafficking and the extent to which officials or government employees are complicit in severe forms of trafficking.

The Trafficking in Persons report “is an important means to shine light on modern-day slavery and to press governments to do more to eradicate it,” the organizations state. Maintaining the Tier 3 ranking not only accurately reflects the reality on the ground, they say, but will help press the governments to take meaningful steps to end forced labor. The letters were sent to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Ambassador Patricia Butenis, acting director of the State Department’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons.

A report released this month found that extortion and bribery fueled the forced labor behind Uzbekistan’s cotton harvest in autumn 2014, a coerced mass mobilization that took teachers, health care workers and millions of other employees away from their duties for several weeks.

In Turkmenistan, tens of thousands of teachers, doctors and other public employees were forced, under the threat of dismissal, to spend four months in the cotton fields, according to a 2014 report by Alternative Turkmenistan News. “The working and living conditions of the forced laborers were abysmal, with people often having to sleep in the open air, drink ditch water and bathe in irrigation channels.”

The U.S. Trafficking in Persons report, issued annually for the past 14 years, covers 188 countries and was mandated by the 2000 Trafficking Victims and Protection Act. The act sets standards to eliminate trafficking and creates enforcement measures, such as the withholding or withdrawal of U.S. non-humanitarian and non-trade-related assistance for countries with low rankings.