Jun 4, 2015

Zimbabwe’s economy is in deep decline, making it harder for average Zimbabweans to work and live, and leaving them less and less confident in their future, according to Solidarity Center Regional Program Director for Africa Imani Countess, in testimony yesterday on Capitol Hill.

“Most workers earn salaries far below the poverty level, and many workers—even in the formal sector—go for months without receiving their wages,” Countess said. (Read her full testimony here.)

Countess was among three panelists speaking at a hearing on the Future of U.S.-Zimbabwe Relations, held by the U.S. House Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations.

She cited a recent AfroBarometer survey of 2,400 randomly selected participants that details the extent of Zimbabwe’s economic crisis:

- 33 percent of respondents in urban areas had gone without food at least once this year.

- 52 percent in urban areas had gone without medical care.

- 59 percent in urban areas had gone without water.

- Nearly two-thirds say “unemployment is the biggest problem government should address.”

According to the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions, Countess said, “most human rights defenders, like trade unions and civic organizations have been severely weakened due to economic decline as well as brain drain.”

Countess told lawmakers that Zimbabwe labor unions and workers are looking for U.S. policy that includes strong support for human rights defenders and community-based, mass organizations that work to educate and organize citizens around a rights-based culture. Zimbabwe unions also seek U.S. support to provide stronger protection for informal economy workers, that in turn, can positively influence the flow of economic migrants.

Other panelists included Shannon Smith, U.S. State Department deputy assistant secretary for the Bureau of African Affairs and Ben Freeth, Mike Campbell Foundation executive director.

Jun 2, 2015

Reports that at least 41 government officials have been charged in the deadly 2013 collapse of Rana Plaza in Bangladesh “represent a long-delayed step toward justice,” says Solidarity Center Asia Regional Program Director Tim Ryan.

“Finally, after more than two years, the Bangladesh government is moving toward holding accountable those who were responsible for the deaths and injuries of hundreds of women and men toiling for pennies in those five garment factories,” Ryan says. “Rana Plaza was the Bangladesh’s worst-ever industrial disaster, and ensuring the justice process works is the absolute minimum the government can do for those who lost loved ones or were injured in the Rana Plaza disaster.”

Sohel Rana, the owner of the building; his parents, the owners of several factories in the building; and at least a dozen government officials were formally charged yesterday, according to the New York Times, citing a state prosecutor, Anwarul Kabir, who is part of the legal team that will pursue the case. At least 17 individuals have been charged with murder, while others face lesser charges, like violating building codes.

More than 1,100 garment workers, mostly women, were killed when the multistory Rana Plaza building pancaked on April 24, 2013. Thousands more were severely injured, many of them now unable to work and support their families. The building housed five garment factories.

A Bangladesh government inquiry in May 2013 concluded that substandard construction materials and the vibration of heavy machinery in the five garment factories were prime triggers of the building’s collapse. Sohel Rana, a prominent leader in the nation’s ruling party, was arrested shortly after over the disaster as he tried to flee to India.

A structural engineer inspecting the building the day before it collapsed found structural cracks, and retail workers in the building were told to stay home. Despite the engineer’s warnings, Rana told factory operators the building was safe. Factory owners then demanded workers return the next day and work; some were threatened with the loss of a month’s pay if they did not go back to the factory floor.

If convicted, the accused could face the death penalty, according to the New York Times, citing Bijoy Krishna Kar, the investigating officer who filed the charges on Monday.

Bangladesh garment factories are notoriously unsafe. Although Rana Plaza served as wake-up call to authorities, factory owners and Western brands, who are now taking steps to remedy the situation, workers still are injured or die on the job. According to data gathered by the Solidarity Center in Bangladesh since November 2012, the garment sector has seen at least 84 fire incidents injuring more than 900 workers and killing more than 31 workers.

Jun 2, 2015

An Uzbek human rights monitor says she was arrested and assaulted as she sought to document the Uzbek government’s forced mobilization of teachers and doctors to clear weeds from cotton fields outside Tashkent, the capital.

Elena Urlaeva, 58, head of the Uzbek Human Rights Defenders’ Alliance, said in an email that she was detained May 31 in the town of Chinaz, after interviewing and photographing teachers forced by government officials to work in cotton fields.

According to Urlaeva, police injected her with unknown sedatives and interrogated her for 18 hours. During the interrogation, the police struck her in the head. While the police held her, doctors probed Ms. Urlaeva in the vagina and anus until she bled, and took X-rays, after accusing her of hiding a data chip. She was denied access to a toilet, ordered to relieve herself outside and photographed nude. The police threatened more physical violence and confiscated her camera, notebook and information sheet of International Labor Organization conventions.

“I have never experienced such humiliation in my life, Urlaeva said. “The police were laughing and enjoying humiliating me.”

Urlaeva also photographed 60 physicians pressed into work in the cotton fields by city hall officials. Kindergarten teachers told her that the mayor had ordered the schools to send them to weed the fields.

Uzbekistan operates what is perhaps the world’s largest state-organized system of forced labor, forcibly mobilizing more than a million of the country’s citizens to pick cotton each fall, as documented by the Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights and the Cotton Campaign.

The Cotton Campaign, a global coalition of labor, human rights, investor and business organizations that includes the Solidarity Center, says “the violent response by the Chinaz police reflects an essential element of the government’s forced labor system: the use of coercion—imprisonment, assault, harassment and intimidation of citizens reporting human rights concerns.”

Steve Swerdlow, a Bishkek-based Central Asia researcher for Human Rights Watch, says Urlaeva’s detention on May 31 and alleged abuse while in police captivity represents “a new low by the Uzbek government” and an effort to “brutalize the country’s civil society.”

The Cotton Campaign is demanding the government of Uzbekistan conduct a transparent investigation of Uraleva’s assault, bring to justice the public officials responsible and issue a public commitment to allow independent human rights organizations, activists and journalists to investigate and report on conditions in the cotton production sector without facing retaliation.

At least 17 people died due to unsafe working conditions during last fall’s harvest, in which teachers, medical professionals and students were forced to pick cotton without any time off and with little or no protective gear, such as gloves. Children often had no classes during these weeks because teachers were working in the fields. Clinics and hospitals had few or no medical personnel.

The most recent U.S. Department of Labor’s annual “Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor” placed Uzbekistan among 12 other countries at the bottom of the report’s rankings and one of three, along with the Democratic Republic of Congo and Eritrea, that received the assessment as a result of government complicity in forced child labor. Uzbekistan is also among 23 countries that received the U.S. State Department’s lowest ranking regarding forced labor and human trafficking in 2014.

On March 19, the Uzbek government arrested, detained, deported and banned from the country Dr. Andre Mrost, an international labor rights consultant, whose firm, Just Solutions Network, Ltd., has bid on a contract to implement a feedback mechanism also called for under the terms of the World Bank loans.

May 20, 2015

Protesting laws that facilitate mass layoffs and enable large-scale subcontracting of workers’ jobs, tens of thousands of Peruvian mineworkers launched a strike Tuesday at the nation’s gold, copper, tin and silver mines in regions such as Cerro de Pasco, Puno, Ancash, and Huánuco. Marching in the main square of Juliaca yesterday, mineworkers shouted, “Down with the outsourcing law, mineworkers unite!”

The Mineworkers Federation describes the outsourcing law and why it needs to be repealed in this brochure.

Members of the Mineworkers Federation (FNTMMSP), a Solidarity Center ally, are seeking to halt worker layoffs and prevent passage of a proposed law that, among other detrimental outcomes, would allow 10 percent of workers to be fired when a company reports losses. They are demanding the government repeal outsourcing legislation that union leaders say enables employers to divide the workforce and violate worker rights. (The Mineworkers Federation describes the outsourcing law and why it needs to be repealed in this brochure.)

The Federation is calling for all outsourced workers who currently perform core functions of mining operations to be moved into permanent contracts and also seeks modifications in legislation that would allow outsourced workers to benefit from annual profit sharing, which is the legal right of directly-employed mineworkers.

Further, the Federation is calling for a repeal of additions to Peru’s Health and Safety Law, enacted last July at the request of employers, which make it more difficult for injured workers or their families to hold employers accountable for workplace injuries, among other harmful measures.

Ivan Granados, a mineworker, said employers already are using the mass layoff legislation. Granados told Telesur that “at work, they are starting to fire the workers, saying that the company is losing money. They are … harassing people with threats of firing them. That is why we are here fighting.”

Mining accounts for up to 15 percent of the Peru’s gross national product, and mining exports have grown 4.7 percent over the past year.

“The mineral wealth of a country should be used for the benefit of the people, including the workers, and not to destroy the environment for the benefit of the corporations and politicians,” say United Steelworkers (USW) President Leo Gerard and Sindicato Nacional de Mineros President Napoleón Gómez Urrutia in a joint statement backing the mineworkers.

The USW and Sindicato Nacional de Mineros, whose solidarity statements were read at a press conference yesterday, are part of a broad coalition of supporters Peruvian mineworkers are engaging, one that includes the Confederación General de Trabajadores del Perú (CGTP), unions from the telecommunications, textile/apparel and oil/petroleum industries, as well as independent unions—Red Solidaria—and student and youth organizations. A coalition of students, young workers and unions earlier this year successfully repealed a law that reduced salaries and benefits for workers under age 25.

The Mineworkers Federation and its affiliated unions built the campaign to address outsourcing in the mining sector following Solidarity Center trainings and workshops, begun last year, in which they gained information about documenting worker rights violations and developing a policy proposal to improve outsourcing legislation.

Over the past six months, the Solidarity Center also has supported regional workshops for Federation affiliates to raise awareness and collect more information about how outsourcing is undermining decent working conditions—including health and safety in the mines—freedom of association and the right to collectively bargain in Peru’s mines.

The Mineworkers Federation also has filed a lawsuit alleging that the outsourcing law is unconstitutional, which has been accepted by Peru’s Constitutional Court for review.

May 19, 2015

More than 60 percent of workers worldwide, predominantly women, are in temporary, part-time or short-term jobs in which wages are falling, a growing trend that is fueling global income inequality and poverty, according to an International Labor Organization (ILO) report released today.

“This report reveals a shift away from the standard employment model, in which workers earn wages and salaries in a dependent employment relationship vis-à-vis their employers, have stable jobs and work full time,” the report states. Further, “labor incomes constitute the main source of income inequality.”

Although the incomes of permanent workers are relatively stable, the percentage of such workers is declining globally—and as few as 20 percent of workers are in permanent jobs in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Many of these precarious jobs are in the informal economy, which includes market vendors, day laborers, pedicab drivers and domestic workers. In fact, domestic workers, most of whom are women, represent 3.6 percent of wage employment worldwide, the report says.

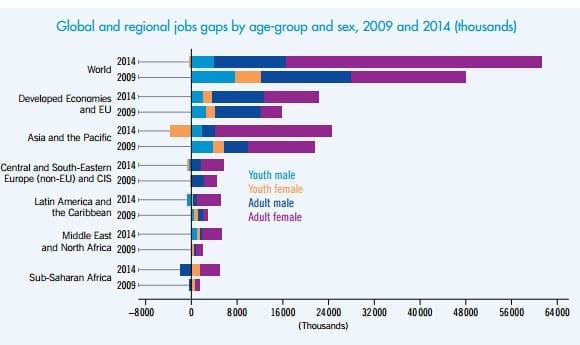

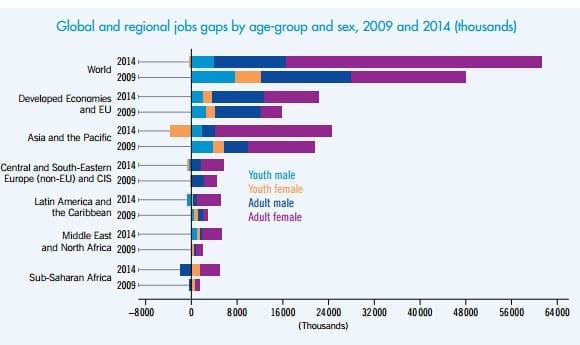

“World Employment and Social Outlook: The Changing Nature of Jobs” cites a shortage in global aggregate demand as a potentially key factor in explaining the slow growth of decent jobs, which has created a global jobs gap that costs an estimated $1.218 trillion in lost wages for workers around the world. The ILO estimates that 201 million women and men were out of work in 2014, more than 30 million higher than before the start of the 2008 global economic crisis.

“A vicious circle may be at work, with lower demand affecting output and employment, thereby further depressing demand,” the report states. In other words, fewer jobs and lower wages mean workers and their families will be able to purchase less, and so fewer jobs will be created and low-pay will be the norm, a vicious cycle that can only be broken by large-scale job creation and incomes that sustain working people and their families.

Workers making low pay are less likely to be union members or to benefit from collective bargaining, according to the report. Further, despite widespread unemployment, in particular among women, there is very limited social protection for unemployed working-age adults. The report recommends policy changes that address the transformation in employment structures and include the growing numbers of precarious workers in social protection systems.

The report also notes that approximately 1 in 5 workers contribute to global supply chains, which “facilitates transitions to the formal economy and waged employment for many workers.” However, the study equally highlights that the vast majority of employment in the global supply chain takes place under poor working conditions. This is particularly the case for vulnerable workers, such as unskilled women, youth and migrant workers.