Apr 12, 2019

In a historic achievement, delegates to the 11th Congress of Brazil’s garment worker union federation, CNTRV (National Confederation of Clothing Workers) last week voted for gender parity in leadership and adopted a pro-women’s rights agenda.

The union achieved parity not only in the overall number of women and men in leadership, but also in its top executive positions.

“Women are empowered at the highest levels in the organization,” said CNTRV President Cida Trajano.

In partnership with the Solidarity Center, CNTRV in recent years ran a nationwide women’s leadership project, preparing women workers to assume leadership positions, according to Trajano.

“This is proof that the effort to form and organize feminist activism is worth it,” she said.

Over the next four years, CNTRV will focus on a pro-women’s rights agenda, including developing programs to combat gender-based violence at work and empower women workers; allow greater space for feminist agendas in communications; consult with women leaders and activists when developing recommendations for public policies affecting women; and expand women’s participation in collective bargaining and wage negotiations.

The Solidarity Center supports women workers seeking greater voice at the workplace across a range of employment sectors in Brazil, including the chemical, garment and hospitality industries, and domestic work. Together with the CNQ (National Confederation of Chemical Workers) CNTRV and CONTRACS (National Confederation of Service and Retail Workers), the Solidarity Center conducts trainings and campaigns to equip women to advocate for safer working conditions and more equitable salaries on the job, and to assume more active leadership roles in their unions.

Nov 19, 2018

On November 25, the Solidarity Center joins our allies around the world in launching 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence. This event highlights the need to end violence against women and girls around the world and pass a global standard to address the full scope of gender-based violence at work.

Solidarity Center Gender Specialist Robin Runge

Solidarity Center’s Senior Gender Specialist Robin Runge discusses gender-based violence at work and how unions and our allies are working for passage of a global standard that would address this prevalent, and generally unacknowledged, workers rights violation.

Q.: What is gender-based violence at work?

Robin Runge: Gender-based violence at work, importantly, is being defined by workers around the world and the International Labor Organization (ILO) through the standard-setting process: It is violence and harassment directed at persons because of their sex or gender. This definition is intentionally broad to recognize that people experience a range of behaviors based on their perceived or actual gender or sexual identity. Gender-based violence at work is inclusive of sexual harassment. A classic example of sexual harassment at work is a supervisor or a manager demanding sex from someone who works for them in exchange for keeping their job or for a promotion. This is also a form of gender-based violence and harassment at work. Similarly, a supervisor harassing or physically abusing a male worker who is perceived to be acting female or to be gay. Gender-based violence at work also includes the impact of domestic violence on the workplace. The majority of workers who experience gender-based violence at work are women because of social and economic inequality, which makes women more vulnerable to these forms of abuse and harassment. However, men also experience gender-based violence and harassment at work.

Q.: Why is gender-based violence and harassment at work a worker rights issue?

RR: Gender-based violence and harassment is one of the most insidious and pervasive worker rights violations. In fact, it is impossible to achieve other worker rights goals such as gender equality, and safe and decent work, if we don’t address gender-based violence. Gender-based violence and harassment at work prevents all workers from being able to assert their rights to freedom of association and speech in the workplace and to take part in collective action about wages and working conditions.

We know that the rates of gender-based violence, although they vary from sector to sector, are extraordinarily high. So for example, we know that in Cambodia, beer promoters, who are mostly women, more than 80 percent of them have been sexually harassed on the job. In many sectors, especially where women are the majority of workers, including the garment sector, and the service industry, the majority of workers report experiencing forms of gender-based violence and harassment. Something that impacts the majority of the workers in a particular sector is a core labor and union issue.

Q.: What’s being done to address gender-based violence and harassment at work?

RR: Workers, including domestic workers, precarious workers, part-time workers, street vendors and the unions that represent them began advocating for a global standard to end gender-based violence in the world of work in 2013. Workers know from their experiences that a global ILO standard applies to all industries and all countries around the world, thereby ensuring that workers throughout the supply chain benefit from the same protections. Over several years of a global campaign, led by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC)—and we at the Solidarity Center were a huge part of this effort—workers and unions were successful in having the ILO place a discussion about the need for a standard to end gender-based violence in world of work on their agenda.

In June 2018, at the annual International Labor Conference, the first negotiations took place among workers, governments and employers on a standard to end violence and harassment in the world of work. The second and final set of negotiations will take place in June 2019.

Q.: How have unions led in efforts to end gender-based violence and harassment at work?

RR: Unions really have been the catalyst for change in this area. And the Solidarity Center has played a critical role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power to achieve this. Gender-based violence is hidden. As individuals who experience this, women are socially and culturally trained not to speak of it. Women are also often afraid that if they speak about it, they will be be retaliated against, including more physical abuse or sexual abuse. Since many people who experience gender-based violence and harassment don’t speak about it, it’s as if it’s not happening. Moreover, workplace structures can create environments that permit and perpetuate these abuses. Workers coming together in unions and other collective worker action provides a mechanism whereby workers can overcome these barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work.

Q.: What can unions and their allies do to ensure ratification of the ILO standard?

RR: We’re in the middle of the two-year standard-setting process during which the ILO has provided opportunities for governments, employers and worker rights organizations to submit comments on draft language and participate in negotiations at standard setting meetings in June 2018 and June 2019. The Solidarity Center has supported our union partners, encouraging them to participate in this process and thereby ensuring that the voices of workers are driving the content of the standard. In particular, participation of our partners has led to the development of definitions of violence and harassment, gender-based violence, “world of work,” and worker that are broad and inclusive of all workers’ experiences, including women workers in precarious, part-time and informal work.

Mar 15, 2018

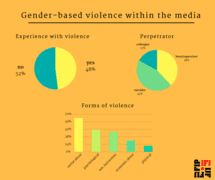

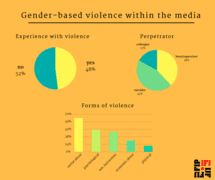

Nearly one in two women journalists have experienced sexual harassment, psychological abuse, online trolling and other forms of gender-based violence (GBV) while working—yet “up to three-quarters of media workplaces have no reporting or support mechanism,” says broadcast journalist Mindy Ran, citing results of a survey survey released this month by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ).

Ran, IFJ Gender Council co-chair, overviewed the survey findings yesterday at the panel, “Challenging Impunity and GBV against Women Journalists and Media Workers,” one of dozens of parallel events taking place this week in conjunction with the 62nd session of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) in New York City.

Credit: IFJ

Without safe and structured systems for reporting gender-based violence at work, employees are less likely to seek assistance—and, as the survey found, 66 percent of journalists who had experienced some form of gender-based violence said they had made no formal complaint.

“It is clear that the current approaches have had limited impact. We’re here to get practical,” says Ran, who opened the panel which included six experts in media and gender-based violence from around the world.

Journalists, like other workers, also experience gender-based violence outside their workplace while doing their jobs. The IFJ survey of 400 women in 50 countries found that 38 percent of perpetrators were a boss or supervisor and 45 percent were people outside of the workplace (sources, politicians, readers or listeners). Thirty-nine percent were anonymous assailants, such as through cyber bullying.

Gender-based Violence at Work: Global Issue Needs Global Solution

Mexico, one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, has seen a “severe increase in violence against women journalists both online and offline,” says Aimée Vega Montiel, a research specialist in feminist communications at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and vice-president of the International Association for Media and Communication Research (IAMCR). Yet there is a “cycle of impunity” and “media companies are not ensuring safety for women journalists,” she says.

Zuliana Lainez Otero, president of the Latin American Federation of Journalists and IFJ executive council member, agrees. “Media owners, at least in Latin America, don’t offer protection,” says.

Marieke Koning from the ITUC and the CLC’s Vicky Smallman joined the IFJ discussion on gender-based violence at work. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

Gender-based violence occurs around the world, and is one of the most prevalent human rights violations. Yet few laws address even some forms of gender-based violence at the workplace, and those are not enough or not enforced, further enabling employers to ignore the issue. Marieke Koning, International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) policy advisor for gender equality, discussed how union activists, women’s rights champions and their allies can take action by joining the ITUC campaign for passage of an International Labor Organization (ILO) convention (standard) covering gender-based violence. Workers around the world could have access to a binding international standard covering gender-based violence at work after it is finalized.

The Solidarity Center has joined the campaign, which Koning says can give momentum to gender equality activists around the world, as did the years’ long effort leading to passage of the 2011 ILO Convention on domestic workers’ rights. Like the domestic workers’ campaign, which built powerful support networks around the world, Koning says, “we want to build alliances to pass the gender-based violence convention.”

Male Media Control ‘Should Be Next on Feminist Agenda’

Domestic violence also impacts those at the workplace, and Vicky Smallman, director of Women’s and Human Rights, Canadian Labor Congress (CLC), shared details of a CLC survey of more than 8,000 union members that found 67 percent had experienced domestic violence. Of those, 47 percent say they were prevented from going to work by their abuser and eight percent lost their jobs because of ramifications from their abuse.

Following the survey, the CLC went on help unions negotiate contracts with paid leave for workers experiencing domestic violence, and successfully lobbied two Canadian provinces to pass similar protections. Smallman credits the Australian union movement for taking the lead on the issue.

Several panelists discussed how the lack of data on women’s experiences in the workplace, and the rates of specific forms of gender-based violence at work hamper efforts to define and address the issues. Carolyn Byerly, chair of the Howard University Department of Communication, Culture and Media Studies, described the lack of representation by women in the media documented in Global Report on the. Status of Women in the News Media. As principal investigator of the report, Byerly says the gender imbalances are still valid 10 years after the report was published.

Byerly and others also warned that media consolidation is creating a global web of male structural power that further exacerbates inequities and inequalities in newsrooms and in media coverage.

“The challenge we face is men’s control of media industries. The problem of media conglomerate is rampant around the world and is growing. We must put media ownership control on global feminist agenda,” she says.

Gunilla Ivarsson, former president of the International Association of Women in Radio & Television, discussed the association’s security handbook developed with a focus on women journalists, and ended the program, saying:

“I think we all have been affected in one way or another. It’s important for us to go to action for change.”

Dec 19, 2017

As part of our year in review series, we are highlighting the 12 most popular Solidarity Center web stories of 2017. This story received the most reach on our Facebook page in November. Read the full story here.

Agricultural work remains one of the most dangerous in the world. And women, who comprise between 50 percent and 70 percent of the informal workforce in commercial agriculture, are especially vulnerable to sexual harassment, physical abuse and other forms of gender-based violence at work.

Aug 24, 2017

As a young woman working in her company’s IT department, Jayne Muthoni Njoki was frustrated by what she says were employer attempts to push her around because of her youth and sex. But rather than quit her job, which she contemplated, she ran for a leadership position in her union, determined to work with others to make change on the job—and in society.

“I needed to fight for people whose voice can’t be heard,” she says.

Now 31, Njoki is the only young person in elected leadership in the Central Organization of Trade Unions–Kenya (COTU-Kenya), a Solidarity Center partner, and also president of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC)-Africa Young Workers Committee.

Njoki discussed how she is working through unions in Kenya and around Africa to educate and train young workers, especially young women, this week on the Working Life podcast, hosted by Jonathan Tasini (Njoki’s interview starts at 30:02).

Many Young Workers Work in Jobs that Don’t Pay Enough to Get by

With 71 million young people around the world unable to secure employment and 156 million more working poor because they have unstable income in the informal economy, the lack of jobs that pay living wages “is a global issue,” she says.

“We need to now think of the informal sector. When I talk of informal economy, that’s where you see the majority of young people are based.

“But unfortunately, we don’t think the informal sector is part of the economy.” Enabling informal-economy workers to have a voice through unions and associations is key to advancing their rights as workers—and once the informal economy is organized, “then everything will fall into place,” she says.

Through COTU-Kenya, which she says has encouraged young workers and women to become union leaders, Njoki also is working to create awareness among domestic workers about their rights and advance their efforts to become union leaders. Many are sexually harassed and assaulted, and fearful of speaking out about their treatment, she says.

Women workers and even women leaders “can’t come out because they are afraid, they are threatened. It’s not easy to come out and say ‘this is my right [to not experience gender-based violence on the job]’ as a young person, as a young lady.”

As she takes on the challenges facing young workers, Njoki is optimistic about the future. “So many ladies, even young people and young men, they are ready to listen and they are ready to work together so we can drive the agenda together.”