Nov 5, 2014

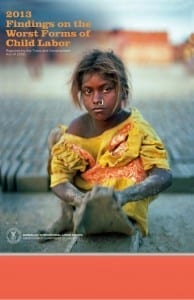

A child picks cotton in Uzbekistan, part of the government’s forced labor system. Photo: Cotton Campaign

An estimated 5.5 million children labor in factories, brick kilns, farm fields and as domestic workers, exposed to dangerous and deadly working conditions and unable to attend school.

And 5.5 million is the number of signatures the nonprofit coalition End Child Slavery Week is seeking on a petition urging the United Nations (UN) to step up its focus on child slavery in the world body’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). The SDGs map the desired direction of member countries for the next 15 years.

The signatures will be hand-delivered to UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon as part of a broader campaign to revise the SDGs to incorporate a sharper global focus on addressing all forms of child labor, including enactment of appropriate laws to set and enforce a minimum age for employment, and measures to ensure that children go to school.

Help the campaign reach its goal: Sign the petition now.

“The number of child slaves has remained constant in the last two decades,” says Kailash Satyarthi, who won the Nobel Peace Prize this year for his work as a child rights’ activist. Child labor is a “largely neglected, ignored, denied aspect of human rights. Governments are saying they don’t have child labor” but “these children remain hidden behind the demonstrations of progress and modern images of government.”

In 1998, Satyarthi created the Global March Against Child Labor, a coalition of unions and child rights organizations from around the world, to work toward elimination of child labor. Global March members and partners are now in more than 140 countries. Many of these civil society groups, including the Solidarity Center, came together this year to launch End Child Slavery Week, focusing on improving the Sustainable Development Goals.

The mass mobilization campaign around the petition will ramp up November 20–26 with a week of public education focused on child labor and trafficking.

Part of the education process involves making the connection between jobs that do not pay living wages and the subsequent need for parents to take desperate actions to support their families, such as sending their children to work, says Satyarthi. If workers had the ability to freely form and join unions to improve their working conditions, they could improve their wages and support their families, he says.

“If parents can’t buy for themselves, how can they buy for their children?” he asks.

You can get the word out by signing and sharing the petition and through Facebook and Twitter @ECSWeek with the hashtag #endchildslaveryweek.

Oct 10, 2014

Labor and human rights activist and long-time Solidarity Center ally Kailash Satyarthi won the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize, the Nobel committee announced this morning. He shares the prestigious award with Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani girl who survived a brutal 2012 Taliban attack for her stance on girls’ education.

As a grassroots activist, Satyarthi has led the rescue of more than 78,500 child laborers and survived numerous attacks on his life as a result. As a PBS profile describes Satyarthi’s work: “His original idea was daring and dangerous. He decided to mount raids on factories—factories frequently manned by armed guards—where children and often entire families were held captive as bonded workers.”

Solidarity Center Asia Regional Director Tim Ryan said, “Kailash’s lifetime commitment to the cause of eradicating child labor is an inspiration to every human rights defender around the world to promote the rights of the most vulnerable, the most economically exploited young workers and the paramount importance of finding ways to secure basic education for all children around the world.”

Satyarthi’s decades of work to end exploitive child labor have encompassed advocacy for decent work and working conditions for adults, including domestic workers, because impoverished families must often make the difficult choice of sending their children to work for the sake of family survival.

“Child labor is a largely neglected, ignored, denied aspect of human rights,” Satyarthi told the Solidarity Center in a recent interview. “This is crime against humanity and is unacceptable in any civilized society.”

In 1998, Satyarthi created the Global March Against Child Labour, a coalition of unions and child rights organizations from around the world, to work toward elimination of child labor. Global March members and partners are now in more than 140 countries. Many of these civil society groups, including the Solidarity Center, came together to launch End Child Slavery Week November 20–26, with the focus this year on pushing the United Nations to make ending child labor a key priority of its 15-year action now under development.

Winning the Nobel “will help in giving bigger visibility to the cause of children who are most neglected and most deprived,” Satyarthi said upon learning he won the prestigious prize. “Everyone must acknowledge and see that child slavery still exists in the world in its ugliest face and form. And this is crime against humanity, this is intolerable, this is unacceptable. And this must go.” (Listen to his interview with the Nobel Prize team.)

At age 26, Satyarthi gave up a promising career as an electrical engineer and dedicated his life to helping the millions of children in India who are forced into slavery by powerful and corrupt business and land owners.

In 1994, Satyarthi spearheaded Rugmark (now known as GoodWeave), the official process certifying that carpets were not woven by children, and aimed at dissuading consumers from buying carpets made by child laborers through consumer awareness campaigns in Europe and the United States.

His life’s achievements encompass a range of human rights work. Satyarthi created a series of “model villages” free from child exploitation, and some 356 villages have emerged in 11 states of India since the model’s inception in 2001. The children of these villages attend school and participate in a wide range of governance meetings to discuss the running of their villages, through child governance bodies and youth groups.

“Showing great personal courage, Kailash Satyarthi, maintaining Gandhi’s tradition, has headed various forms of protests and demonstrations, all peaceful, focusing on the grave exploitation of children for financial gain,” said Nobel Committee Chairman Thorbjorn Jagland said.

Satyarthi’s award of the Nobel Prize is the latest high-profile recognition of worker rights activists in the last month. Earlier this week, Alejandra Ancheita, founder and executive director of the Mexico City-based ProDESC (Project for Economic, Cultural, and Social Rights), won the prestigious international Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders. And in September, Ai-jen Poo, founder and director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, became a MacArthur ‘Genius’ Grant recipient.

Oct 9, 2014

In Uzbekistan, empty classrooms and children working in cotton fields during the annual fall cotton harvest contributed to the country’s ranking as among those with the worst forms of child labor in the world, according to a report released yesterday by the U.S. Department of Labor.

In Uzbekistan, empty classrooms and children working in cotton fields during the annual fall cotton harvest contributed to the country’s ranking as among those with the worst forms of child labor in the world, according to a report released yesterday by the U.S. Department of Labor.

The annual “Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor” placed Uzbekistan among 12 other countries at the bottom of the report’s rankings and one of three, along with the Democratic Republic of Congo and Eritrea, that received the assessment as a result of government complicity in forced child labor.

The report assesses efforts by more than 140 countries to reduce the worst forms of child labor and indicates whether countries have made significant, moderate, minimal or no advancement over the previous year. Thirteen countries were cited as making significant advancement, compared with 10 countries in last year’s report. Among them: Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador, South Africa and Tunisia.

Through a detailed country-by-country description, the report includes data on children’s work and education, national laws and regulations regarding child labor and other key information. Globally, 10 percent of the world’s children—168 million children, of whom 85 million labor in hazardous work—toil in factories, mines and farms, unable to attend school.

Regionally, the report cites sub-Saharan Africa, home to 30 percent of the world’s child laborers, as the area with the largest number of children working in hazardous conditions. An estimated 59 million children ages 5–17 are engaged in child labor in sub-Saharan Africa, or 21.4 percent of all children in the region.

Elsewhere, 77.8 million children ages 5–17 are engaged in child labor in the Asia and Pacific region, some 9.3 percent of all children in the region. In Latin America and the Caribbean, 12.5 million children work, accounting for 8 percent of all children in the region. In the Middle East and North Africa, 9.2 million children—8 percent of all children in the region—are engaged in child labor.

A list of goods produced by child or forced labor also is included as part of the report, which this year is dedicated to retiring Rep. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa). Harkin, a champion of worker rights, has long led the fight to end child labor globally, and spearheaded legislation in 2000 that mandated compilation of the annual “Findings of the Worst Forms of Child Labor.”

Jul 13, 2014

Child labor survivor Evelyn Chumbow is working to end the trafficking of children. Credit: Solidarity Center

At age 9, Evelyn Chumbow was trafficked overseas from Cameroon to become a domestic worker for a family in Maryland. She worked from 6 a.m. to midnight, seven days a week, was forced to sleep on the floor without a room of her own and regularly beaten. Each day, she took her employer’s children to school, but was not allowed to attend. At 17 she escaped, but had no identification and didn’t know her birthday or age.

“There was no where to run and get help,” says Chumbow. Now a student at the University of Maryland, Chumbow spoke at a briefing yesterday on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., where panelists discussed efforts to address child labor, especially among domestic workers.

Some 168 million children toil in fields, in brick kilns and at industrial settings around the world, receiving little or no formal education and likely to remain in the cycle of poverty that led to their arduous labor. Although child labor has decreased globally in recent years, child labor in domestic work has increased by 9 percent in the past four years, Jo Becker, advocacy director at Human Rights Watch, said at the briefing. The International Labor Organization (ILO) says nearly half of child domestic workers are under age 14, and nearly all are girls.

The briefing, “Promoting the Rights of 15 Million Domestic Workers,” hosted by a bipartisan group of U.S. Senate and House members, marked World Day Against Child Labor. Observed each year on June 12, the day is a time to remind the world about the plight of child laborers and spur action to end the scourge. The Child Labor Coalition and the Alliance to End Slavery & Trafficking (ATEST) sponsored the event.

Tiffany Williams from the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA), pointed out that child labor in domestic work involves a similar “pattern of abuse” around the globe: Employers hold the workers’ passports, making it difficult for them to leave; workers are paid low wages or sometimes not paid at all and are forced to toil for long hours, working weeks or months without a break. David Diggs, executive director of Beyond Borders, also took part in the panel.

Many child laborers who work in domestic service also are trafficked, as Chumbow was, a point made by Tim Ryan, Solidarity Center Asia Regional Program director, who moderated the panel. Many labor recruiters charge exorbitant fees for their services, forcing workers into debt bondage, falsify documents and deceive workers about their terms and conditions of work increasing vulnerability to human trafficking.

Around the world, millions of workers are unable to find jobs or are paid wages too low to support their families—and many children work to help their families survive.

They turn to work in the informal economy, where pay is erratic, workplace safety and other labor laws do not apply, and the social protections granted to formal economy workers are non-existent.

“As a society, we have to ask why this is happening,” said Williams. “Domestic work is one of the few ways less educated women can care for their families.”

Eliminating child labor will succeed in large part when adults have decent work—a connection recognized by participants at last year’s Third Global Conference on Child Labor. The Brasilia Declaration, issued at the International Labor Organization-sponsored conference, calls for “measures to promote decent work and full and productive employment for adults” so that “families are enabled to eliminate their dependence on the income generated by child labor.

Apr 9, 2014

James Kofi Annan describes child labor in Ghana. Credit: Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks

Reducing and eliminating child labor requires a focus on decent work for adults, said Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau, speaking yesterday on Capitol Hill. Such an approach, she said, must build the capacity of vulnerable workers to negotiate the terms of their employment and to advocate for local and national policies that address the economic welfare of entire communities.

Bader-Blau joined a panel of experts in a congressional briefing, “Combating Exploitative Child Labor,” sponsored by the Alliance to End Slavery & Trafficking (ATEST), a coalition spearheaded by the nonprofit Humanity United, and the Child Labor Coalition—both of which include the Solidarity Center. (Watch a video of the full event.)

More than 168 million children around the world are engaged in child labor. David Abramowitz, vice president for Policy and Government Relations at Humanity United and a participant in the discussion, defined child labor as work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and which interferes with children’s education. In the most extreme forms, children are enslaved, separated from their families or exposed to serious hazards and illnesses.

Another participant in the event, James Kofi Annan, was enslaved as a child laborer in Ghana, where he was forced to work as a fisherman on Lake Volta in the coastal town of Winneba.

“I know what it means to go through torture,” said Annan, who went on to become an advocate to end child labor. Annan founded Challenging Heights, where 800 former child laborers now attend school in the Winneba community. He also operates a shelter for 50 children rescued from the worst forms of child labor.

Annan introduced Sen. Tom Harkin, a long-time champion of ending child labor, who pushed for the International Labor Organization (ILO) standard on eliminating the worst forms of child labor (Convention 182) and sponsored the Harkin-Engel Protocol, which addresses child labor in the cocoa industry. Harkin also spearheaded the creation of the Labor Department’s annual report on the List of Goods Made with Forced Labor or Child Labor.

“It’s not just enough to get these kids out of the worst forms of child labor. We have to build schools, we have to hire teachers,” Harkin said. Although he is retiring from the Senate this year, Harkin, who has traveled to Ghana several times to investigate child labor, said he would continue to be involved in the issue.

Getting children out of work and into school is the outcome of a path-breaking collective bargaining agreement workers reached at the Firestone plantation in Liberia, said Bader-Blau. After forming a union, the workers, with assistance from the Solidarity Center, negotiated a reduction in the high daily production quota of latex. Parents had been forced to bring their children to work to meet the high quotas. The new union, FAWUL, negotiated lower daily quotas so adult workers could meet them, and achieved free accessible education for the workers’ children.