Mar 25, 2015

The United States and India are connected by a common philosophy and a common history of resistance to oppression. And trade unions are key to greater equality and inclusion, said Fred Redmond, international vice president of the United Steelworkers, at a conference in Delhi this week that focused on how democracy in Asia can be strengthened through inclusion, participation and rights.

“Today in the United States and around the world, social cohesion is threatened by rising inequality and the economic and social marginalization of large segments of the population. The breakdown of institutions, such as labor unions, that promote equality and opportunity and participation, creates not only a skewed distribution of resources but also a breakdown of trust,” said Redmond, who joined with Nobel Peace Laureate Kailash Satyarthi Monday to explore the global march for dignity and democracy.

They highlighted the common thread running through social movements around the world: Gandhi’s philosophy of peaceful disobedience, which brought India independence, shaped the U.S. civil rights movement and continues to serve as a foundation for people around the world seeking justice and equality. Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau moderated their discussion.

Satyarthi, founder of Global March Against Child Labor and a lifelong campaigner for children’s rights, emphasized that the lack of economic security hinders the flourishing of democracy. When workers have no jobs, they also have no opportunities to join unions, which enable them to secure living wages and social protections like health care, said Satyarthi. He added that workers who lack economic security are often forced to send their children to work. The Solidarity Center has worked closely with Satyarthi for years to help end child labor.

Satyarthi and Redmond made their remarks as part of a panel discussion at the Strengthening Democracy in Asia conference organized by the Institute of Social Sciences (ISS), Asia Democracy Network and the World Movement for Democracy held March 23–24.

Also at the event, Solidarity Center Asia Director Tim Ryan moderated a panel discussion on strategies to promote democracy among marginalized workers featuring Redmond; Manali Shah, national secretary of the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA); and Ramachandra Khuntia, vice president of Building and Wood Workers International.

Feb 3, 2015

A coalition of worker and human rights organizations, including the Solidarity Center, is urging the U.S. State Department to maintain Uzbekistan’s rank at the bottom of its “Trafficking in Persons” report when it is released this year. (Read the full document.)

“In 2014, the government of Uzbekistan forced more than a million citizens to work in the cotton fields under threat of penalty, for its benefit, and as a matter of state policy,” the groups write in a 15-page document detailing the Uzbekistan government’s coercion of public servants and other workers—including children—to toil in cotton fields.

The document notes that at least 17 people died due to unsafe working conditions during last fall’s harvest. Workers forced to pick cotton were not given any time off—including weekends and holidays. Organizations monitoring the harvest reported that workers were provided with no protective gear, such as gloves.

Public organizations, including schools, were required to provide between 30 percent and 60 percent of their staff for the duration of the harvest, and in some cases, up to 80 percent of their staff. Children often had no classes during these weeks because teachers were working in the fields. Clinics and hospitals had few or no medical personnel.

Many employees were threatened with loss of employment, loss of utilities and other public services, social exclusion, fines, administrative harassment, and criminal prosecution if they did not participate in the cotton harvest, the report states.

The 2014 Trafficking in Persons report gave Uzbekistan a “Tier 3” ranking, a designation that indicates a country is not complying with the U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Act’s minimum standards nor making attempts to do so. The coalition says that maintaining the Tier 3 ranking is essential to convey to the Uzbekistan government the need to end forced labor.

A Tier 3 ranking makes countries liable to sanctions, which could include the withholding or withdrawal of U.S. non-humanitarian and non-trade-related assistance.

The coalition further notes that “the government of Uzbekistan’s use of forced labor to produce cotton is supported by its denial of fundamental rights of association, freedom of press and due process to enable its use of forced labor to produce cotton.”

The 2014 Trafficking in Persons report found that Uzbekistan’s “government-compelled forced labor of men, women, and children remains endemic during the annual cotton harvest….There were reports that some children aged 15 to 17 faced expulsion from school for refusing to pick cotton.”

Uzbekistan also was at the bottom of the 2014 Findings on the “Worst Forms of Child Labor” report released in October by the U.S. Labor Department.

Jan 13, 2015

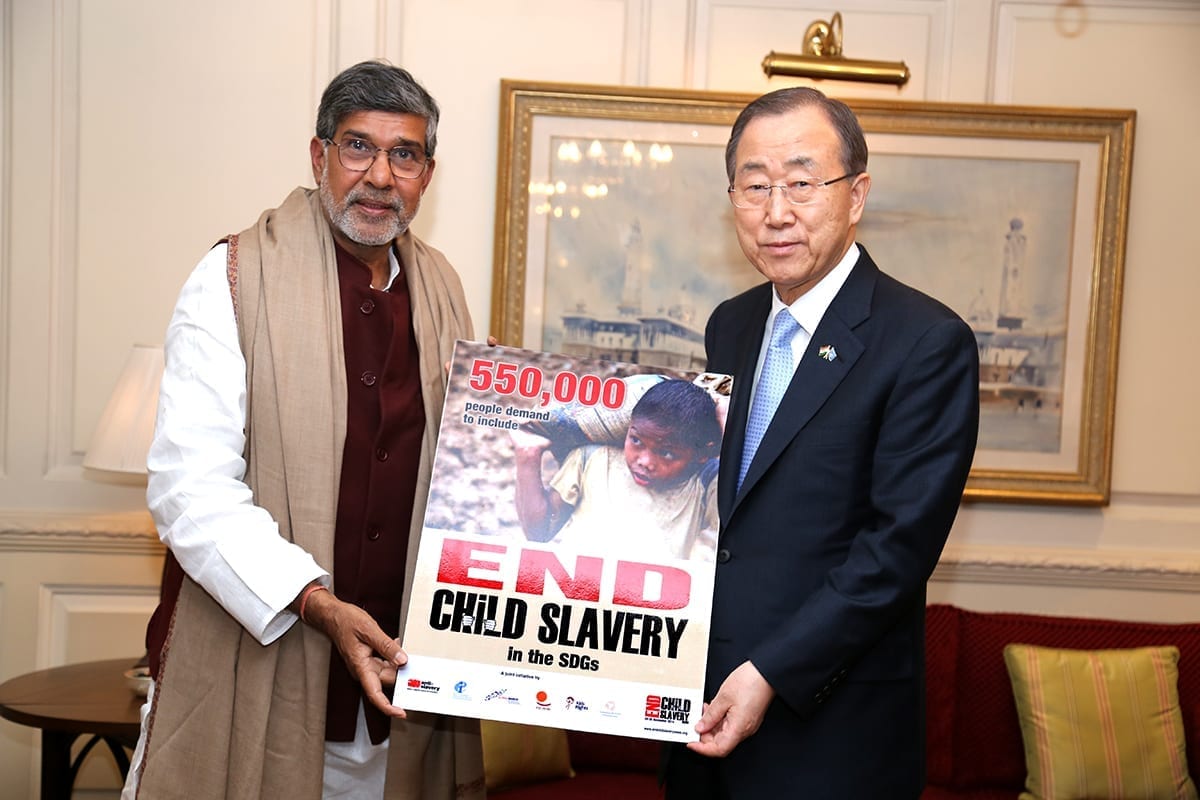

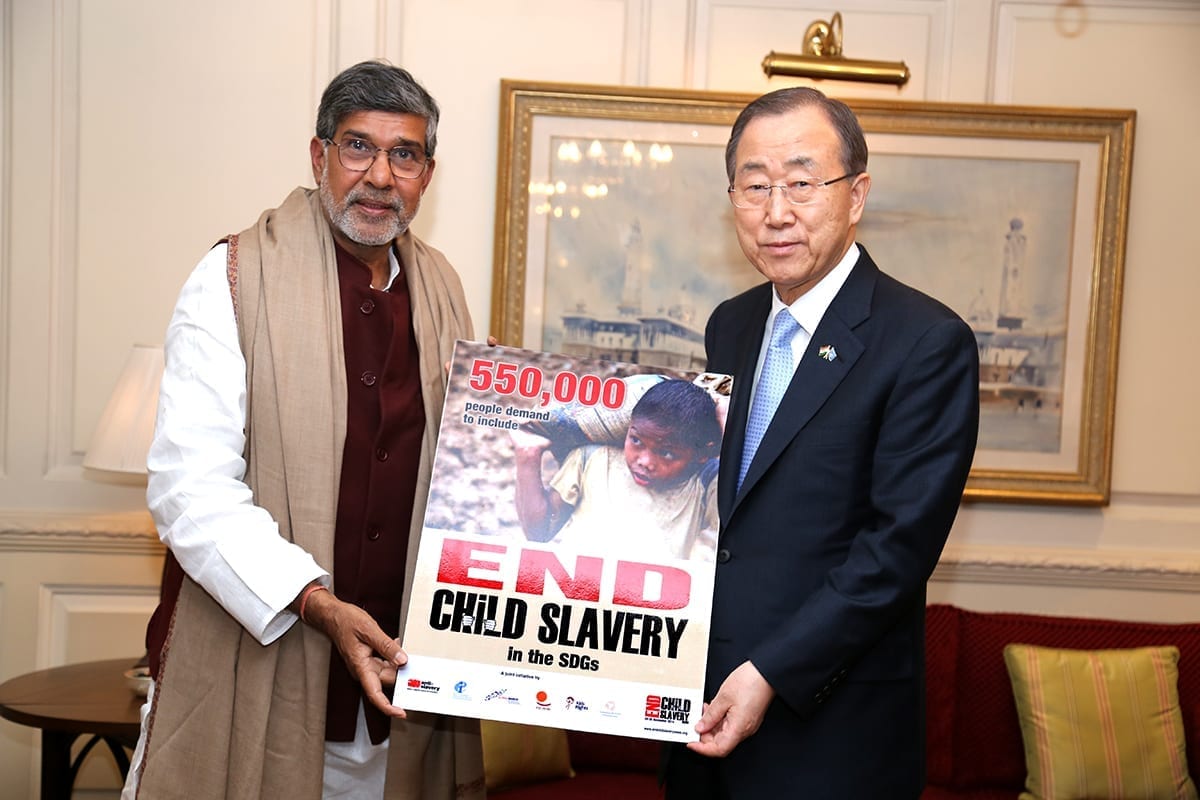

In an historic meeting, Nobel Peace Laureate Kailash Satyarthi delivered a global petition on child labor to United Nations (UN) General Secretary Ban Ki-Moon in New Delhi, India, yesterday. More than 550,000 people around the world signed the petition urging the UN to make abolition of child labor a key part of the world body’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), now under discussion.

“The most shameful commentary of today’s society is that slavery still exists, and our children are the worst sufferers,” Satyarthi said in an address at the event. “There cannot be any excuse for this heinous crime against humanity. There must not be any delay in ensuring their freedom. We have to act now and create a future where all children are free to be children.”

Last November, the Global March Against Child Labor, a coalition of unions and child rights organizations in more than 140 countries, which includes the Solidarity Center, launched End Child Slavery Week, to focus on improving the Sustainable Development Goals. The centerpiece of the campaign involved collecting signatures for delivery to the UN secretary general.

The petition included the exact text for inclusion in the “Outcome Document” of the Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals:

“Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labor, secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor including recruitment and use of child soldiers and child slavery, and, by 2025, end child labor in all its forms.”

Satyarthi, who in 1998 created the Global March Against Child Labor as part of his tireless efforts to end child labor, also discussed with UN officials at the event further steps for ensuring the rights of children globally. Satyarthi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014 for his decades of often dangerous work in rescuing child laborers and providing them with safe havens.

It’s not too late to sign the petition. In the United States, the social mobilization organization CREDO partnered with the Solidarity Center to create a successful petition campaign.

Sign now!

Dec 3, 2014

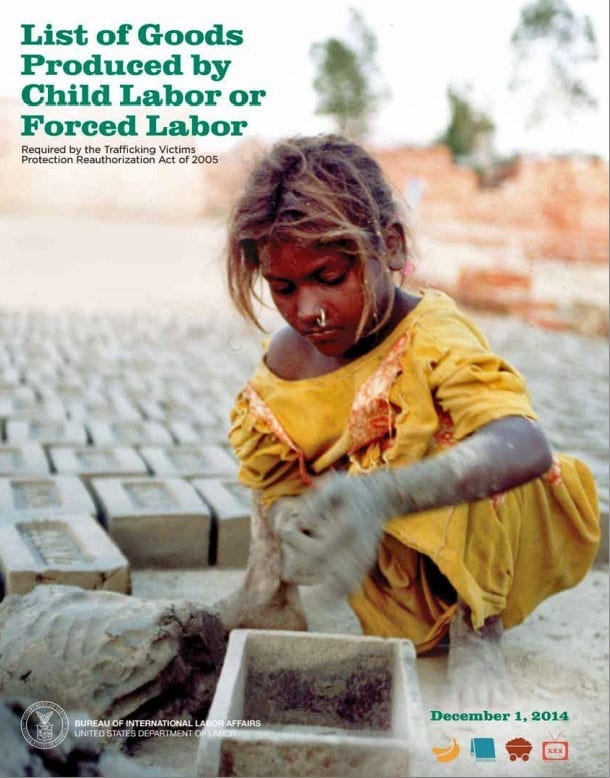

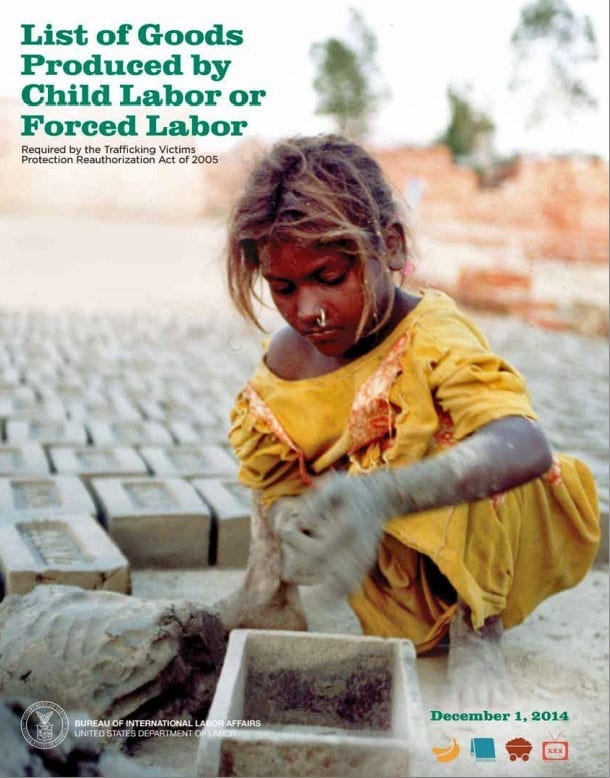

Cotton production involves the most child labor and forced labor in the world, according to the 2014 “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor” by the U.S. Labor Department’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs.

Overall, 126 goods are produced annually by child labor and 55 goods produced through forced labor. Most of the goods, like cotton, are found in common items like T-shirts or are among popular foods, such as melons and rice.

The sixth annual report, released this week, added 11 goods produced with children’s labor: garments from Bangladesh; cotton and sugarcane from India; vanilla from Madagascar; fish from Kenya and Yemen; alcoholic beverages, meat, textiles and timber from Cambodia; and palm oil from Malaysia. Electronics from Malaysia made the list for being produced with forced labor.

Uzbekistan, listed among countries using forced labor, including children, for cotton production, routinely requires teachers to leave classrooms and work in the country’s annual cotton harvest, according to a report the Uzbek-German Forum issued last month.

The lengthy list of goods produced with child labor and forced labor includes garments, fish coffee, shrimp and other shellfish, tea, corn, tobacco and peanuts.

See the full list.

Nov 14, 2014

Uzbekistan continued using forced labor, including children, for the country’s recent cotton harvest, with more teachers than ever compelled to toil in the fields this year, according to a report released today by the Uzbek-German Forum.

In schools across the country this fall, 50 percent to 60 percent of all teachers were absent from classrooms at any given time, leaving schools severely understaffed and unable to conduct normal classes.

The report, a preliminary look at Uzbekistan’s state-sponsored labor system of cotton production this season, found that the government forced fewer children to work but replaced them with university students and public- and private-sector employees.

Yet the report documented numerous instances of child labor in several regions and concluded that “these cases indicate that the government of Uzbekistan has not undertaken durable, structural reforms to eliminate definitively child labor in Uzbekistan. Nor has the government made it clear to local officials that child labor will not be tolerated and task them with enforcing laws prohibiting child labor.”

The assessment parallels that of the U.S. State Department, which in October placed Uzbekistan among 12 countries with the worst forms of child labor. The State Department report, “Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor,” listed Uzbekistan as one of three countries, along with the Democratic Republic of Congo and Eritrea, that received the assessment because of government complicity in forced child labor.

The Uzbek-German Forum report, compiled by experienced researchers in six regions of Uzbekistan as well as the capital, Tashkent, found a large number of injuries and deaths during this season’s harvest, including at least 17 people who died and 35 who were injured after being struck by cars or tractors. Individuals forced to pick cotton were housed in garages, unused farm buildings or local schools, nearly all of which were unheated and without water or hygiene facilities.

For decades, more than 1 million Uzbeks have been forced to pick cotton each fall. They are threatened with the loss of jobs, social benefits and public utilities if they do not participate. Many face fines and criminal prosecution, according to the report.

Profits of Uzbek’s cotton sector support only the government, according to the Uzbek-German Forum. Farmers are forced to meet state-established cotton quotas, purchase supplies from one state-owned enterprise and sell the cotton to a state-owned enterprise at artificially low prices. The system traps farmers in poverty, and the state profits from high-priced sales to global buyers who use the cotton for goods made by brand-name retail and apparel supply chains.

Read the full report: “The Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights Preliminary Report on Forced Labor During Uzbekistan’s 2014 Cotton Harvest,”