Dec 3, 2014

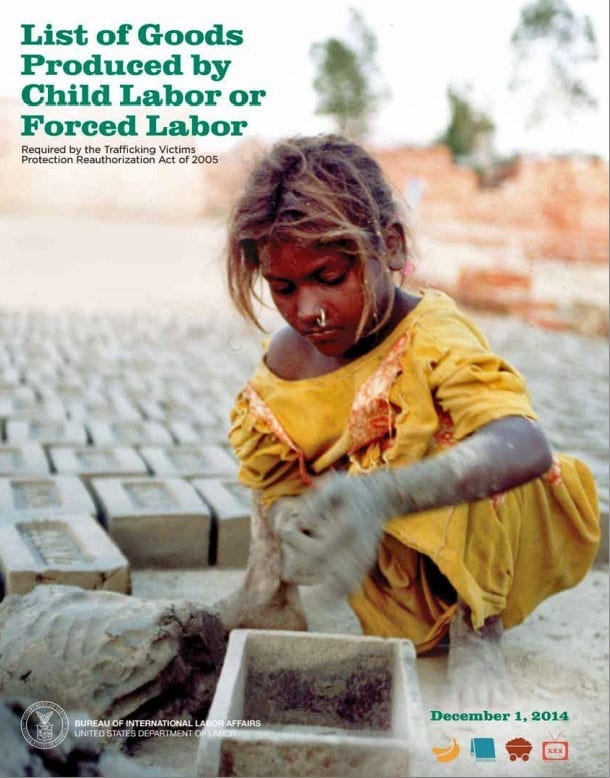

Cotton production involves the most child labor and forced labor in the world, according to the 2014 “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor” by the U.S. Labor Department’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs.

Overall, 126 goods are produced annually by child labor and 55 goods produced through forced labor. Most of the goods, like cotton, are found in common items like T-shirts or are among popular foods, such as melons and rice.

The sixth annual report, released this week, added 11 goods produced with children’s labor: garments from Bangladesh; cotton and sugarcane from India; vanilla from Madagascar; fish from Kenya and Yemen; alcoholic beverages, meat, textiles and timber from Cambodia; and palm oil from Malaysia. Electronics from Malaysia made the list for being produced with forced labor.

Uzbekistan, listed among countries using forced labor, including children, for cotton production, routinely requires teachers to leave classrooms and work in the country’s annual cotton harvest, according to a report the Uzbek-German Forum issued last month.

The lengthy list of goods produced with child labor and forced labor includes garments, fish coffee, shrimp and other shellfish, tea, corn, tobacco and peanuts.

See the full list.

Nov 25, 2014

Violence against women takes many forms, and can happen in the home, in public spaces—and on the job. At the workplace, 35 percent of women worldwide have experienced violence.

This November 25, International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, unions around the world are calling for the International Labor Organization (ILO) to pass an global convention on gender-based violence at the workplace. As the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) points out, “anyone can be a victim of violence at work, but gender-based violence typifies unequal economic and social power relations between women and men.”

Union leaders and allies are re-submitting a proposal to the ILO Governing Body requiring the ILO to develop an international standard to guide governments and businesses in formulating strong laws and policies to prevent and remedy gender-based violence at work. The ILO Governing Body adjourned this month without considering a similar proposal, and will meet again in March 2015. (You can take action through the International Transport Workers’ Federation’s “End workplace violence against women” campaign.)

This fall, workers in the Middle East and North Africa waged rallies and sit-ins to highlight the issue. The General Federation of Iraq Trade Unions (GFITU) organized a solidarity gathering in late October at Al Qushla Square in Baghdad. Hashmeyya Al Sa’adawi,IndustriALL executive board member and president of the electricity union in Basrah, read the statement of the Arab unionist women network, which expressed concern over increased violence against women.

“We believe that the violence against women issue is a crucial matter that requires immediate action,” she stated

In Morocco, the Democratic Labor Confederation (Confédération Démocratique du Travaille, CDT), organized a sit-in outside Parliament to raise awareness about gender-based violence in the workplace and request support for the convention (watch a video clip of the event).

The Jordanian Federation of the Independent Trade Unions sent a letter to the country’s chambers of commerce and industry and Jordanian government officials urging their support for passage of the gender-based violence standards in the ILO Administration Council.

Women disproportionately work in precarious, low-income and informal economy jobs, where there are few mechanisms to prevent violence and exploitation. Women also are the majority in occupations where workers are more likely to be exposed to violence, such as domestic work and health care, the garment and textile industries and in agriculture. Many women do not report physical, psychological or sexual violence fearing they will be fired or because of cultural norms.

An ILO Convention would further acknowledge that violence against women is a human rights violation, and would be an important step to improving women’s working conditions worldwide and saving the millions of dollars spent every year on health care, lower productivity and sick leave because of violence against women,

Nov 25, 2014

Transport workers at Gulftainer in the Iraqi port of Om Qasr port formed a union committee in November following a three-year organizing effort that involved raising awareness among workers about their rights on the job.

Transport workers at Gulftainer in the Iraqi port of Om Qasr port formed a union committee in November following a three-year organizing effort that involved raising awareness among workers about their rights on the job.

Recognizing they would be better able to negotiate for improved wages and working conditions if they were part of a union, some 119 workers have elected three members to a labor committee that will oversee union elections. The union would be an affiliate of the General Federation of Iraqi Trade Unions (GFITU).

The decision to hold elections signifies a key turning point for Iraqi unions, which generally have waited for management approval to form union committees but now recognize that the freedom to form unions is guaranteed by national and international law. Workers at Gulftainer talked with workers outside the workplace, and also reached out to night shift workers. They held an awareness workshop in Basra and an election preparatory meeting, where they discussed the mechanisms of implementing elections, and the participation of night shift workers in elections.

The newly-elected chairman of the union committee and two other workers at Gulftainer previously took part in a Solidarity Center workshop centered on developing organizing skills among worker representatives at companies funded by International Finance Corporation (IFC) loans.

The Solidarity Center is working with Iraqi trade unions to promote international labor standards at worksites, especially those where companies receive IFC loans, by using the performance standard of IFC institutions to protect worker rights. Iraq’s labor code, created under Saddam Hussein, contains significant gaps in areas of discrimination, forced labor and the right to collective bargaining.

Iraqi unions elsewhere are improving working conditions at IFC-funded workplaces, following Solidarity Center training programs, and are documenting violations and negotiating with management to improve working conditions.

For example, at Erbil Rotana Hotel and at Bazian and Tasluja cement factories in Sulimanyya, workers who took part in the trainings sharpened their organizing skills and went on to negotiate improved work contracts so that workers now receive overtime pay, in accordance with Iraqi labor

Nov 21, 2014

November 24 marks the two-year anniversary of the deadly fire at Tazreen Fashions Ltd. in Bangladesh that killed 112 garment workers. Since then, at least 30 garment workers have died in factory fires and 844 have been injured in 68 incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital. Many of the survivors and their families say they have received little or no compensation, and many survivors are unable to work again.

“Things are getting much, much worse for me,” said Shahanaz, who sustained critical injuries, including loss of vision in her right eye, while fleeing the burning building. “With all of the pain I am in, I can no longer pray while standing.”

Shahanaz is one of nearly a dozen garment workers and family members the Solidarity Center profiled last year. Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka recently visited the workers again, and found that, like Shahanaz, their health and financial situations have deteriorated.

Five months after the Tazreen fire, another 1,100 garment workers in five factories were killed and another 2,500 people were injured when the Rana Plaza building collapsed.

Millions of garment workers, up to 90 percent of whom are women, have made Bangladesh the second largest producer of apparel globally, and 80 percent of the country’s foreign exchange depends upon the industry. Garment workers have toiled for decades in hazardous working conditions with few worker rights. After the Tazreen and Rana Plaza disasters shocked the world, these worker rights violations could no longer be ignored.

Following the Rana Plaza collapse, the United States suspended its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreement with Bangladesh based upon chronic and severe labor rights violations. In the weeks after the suspension, the Bangladeshi government dropped charges against two prominent garment union leaders. It has since registered more than 200 unions representing more than 50,000 workers. By contrast, only two garment unions were registered between 2010 and 2012.

Yet some 25 percent of new unions are in factories that have closed or are inactive due to anti-union activities, according to Solidarity Center data. Further, in at least 46 factories with unions, workers have faced severe anti-union violence, mass terminations and/or threats.

International retailers have joined together in two separate groups to improve safety at factories where they contract work. More than 175 international retailers signed on to the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, a legally binding agreement negotiated with the global unions, IndustriALL and UNI. Another 26 primarily U.S. and Canadian companies signed the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, which is not legally binding. After inspecting some 1,700 of Bangladesh’s 5,000 garment factories, the Accord and the Alliance identified 33 factories in which safety issues are so serious that they recommended production be suspended because of the risk to workers.

However, questions remain about who will pay for the cost of repairs and who inspects the remaining factories that neither the Accord nor Alliance says are their responsibility. The Accord and Alliance claim 1,800 factories are under their purview, but a recent study estimated the total number is between 5,000 and 6,000 factories and facilities.

The Solidarity Center has had an on-the-ground presence in Bangladesh for more than a decade. This year, following Solidarity Center fire safety trainings, garment workers have used their new skills to identify and correct problems at their worksites. Joni and Rabeya, president and general secretary of B. Brothers Garments Co. Ltd. Workers Union, found 15 expired fire extinguishers and located electrical hazards in their factory, such as faulty electrical wiring. They raised these fire safety issues with management, which has since corrected some of the issues.

Recognizing that workers who freely form unions can better advocate for job safety and decent wages, the Solidarity Center believes there is need for:

• A clear and transparent trade union registration process.

• Quick resolution of unfair labor practices by the Bangladesh Labor Department, with penalties for employers who engage in them.

• Development of an independent alternative dispute resolution mechanism in the face of inefficient labor courts

Nov 19, 2014

The Cambodian government announced in recent days it would raise the monthly minimum wage in the textile and apparel industry to $128, an amount workers say falls far short of the amount needed to support themselves and their families and is only $8 above the poverty line.

The new minimum wage also is well below the government’s estimates of wages garment workers need: Late last year, a government-appointed committee announced that a minimum living wage should be between $167 to $177 a month. The minimum wage for garment workers at the time was $80 a month, and even with the increase, Cambodia has among the lowest monthly minimum wage in the industry. Garment-making is Cambodia’s largest industry, accounting for 80 percent of exports.

Tens of thousands of garment workers, the majority of whom are women, have waged a series of mass protests over the past year, demanding a living wage. In January, Cambodian security forces shot into crowds of striking workers, killing at least five, injuring more than 60 and resulting in the arrests and dismissals of dozens of workers and union leaders.

In September, garment workers again took to the streets, demanding $177 per month and directing their protests at global clothing brands. Following the protests, a handful of global brands, including H&M and Zara, said they would pay more for clothing manufactured in Cambodia.

Some 90 percent of the country’s 600,000 garment workers have no permanent contracts and are instead employed under fixed-duration contracts. Without formal employment, workers on contract fear they will lose their jobs if they demand better working conditions. Garment workers on contract also are prevented from accruing seniority and related benefits, and women workers suffer discrimination when taking maternity leave or tending to other family-related duties.

Download the fact sheet, “Cambodia: The Garment Sector and Poverty Wages.”