Apr 5, 2021

Union women and Solidarity Center partners from the Middle East and North Africa spearheaded a petition calling for governments to ratify International Labor Organization Convention 190, the landmark global labor standard adopted in June 2019 to eliminate violence and harassment in the world of work, including gender-based violence and harassment (GBVH).

“The idea of starting a petition arose during the seminar we held as a collective, ‘Women for the Dignity and Rights of Women’ [where] women from different Arab countries presented their efforts to get their countries to ratify Convention 190,” says Touriya Lahrech, president of the Morocco Contributions Forum, a Solidarity Center partner.

Unions and civil society organizations launched the petition in conjunction with the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women meetings and the Generation Equality Forum in March. Activists from Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen who comprise the Coalition for Women’s Rights and Dignity coordinated with the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) to host the online petition.

The petition is available in Arabic, English, French and Spanish.

Mar 17, 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit workers hard—but women have especially suffered compared with men, experiencing higher rates of unemployment, discrimination and exposure to the virus, and skyrocketing rates of gender-based violence and harassment (GBVH), speakers said this week at a Solidarity Center panel. Unions are organizing to demand that government responses to the pandemic’s economic and social effects center on the needs and experiences of women workers, ensuring safety and respect for all workers.

“Women have suffered because most of the work they do is precarious”—Rose Omamo, Kenya

“Women have suffered because most of the work they do is precarious—they are informal workers, frontline workers,” said Rose Omamo, general secretary of the Amalgamated Union of Kenya Metalworkers. Omamo explained how COVID-19 has shown the need to extend social protections like paid sick leave and health care to all workers, and to address issues affecting women in Kenya and worldwide. She shared that rape and sexual assault in the world of work has increased because of economic stress caused by the pandemic, including an increase in domestic violence and increased demands for sexual favors in order to obtain or keep a job. Kenyan unions are organizing to demand that social protections include access to reproductive health services in light of increased sexual violence, and are bargaining with employers to increase protections against GBVH in the workplace.

Omamo was among five women union leaders and Solidarity Center partners who took part in “Women Workers’ Voices and Participation on the COVID-19 Recovery Front Lines,” a virtual parallel event during the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) as part of the NGO CSW65 Virtual Forum.

Employers, Government Failing Women Workers in the Pandemic

Employers have used COVID-19 as an excuse to violate worker rights, says Cambodian union leader Ou Tepphallin.

Employers have taken advantage of the pandemic to exploit, abuse and lay off workers, panelists said. “Labor rights have been violated during COVID-19 as employers used the opportunity to exploit the system,” said Ou Tepphallin, president of the Cambodian Food and Service Workers Federation.

Retail, hospitality and garment workers in Cambodia, the majority of whom are women, have not been provided adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) or measures to ensure their safety, and unscrupulous employers have taken advantage of the crisis to exploit and abuse workers. For example, workers in the hospitality sector report that entertainment venues have opened illegally during lockdown and forced workers to return to work. Some companies deliberately targeted older or less conventionally attractive workers for layoffs. Unions have been organizing to hold employers to account, negotiating for better protection measures, including protections from GBVH.

When women are in unions, they can speak out against mistreatment and come together to create solutions, says Honduran union leader Iris Munguia.

In Honduras, the impact of the pandemic collided with ecological and social crises. The devastation caused by two hurricanes in November 2020 left many women homeless and struggling to support their families, said Iris Munguía, women’s coordinator of the Honduran Federation of Agro-industrial Unions (FESTAGRO). In addition, women experience extremely high rates of GBVH, which is treated with impunity in Honduras. More than 30 women have been murdered in 2021, and “there are no investigations of these murders,” Munguia said.

The combined crises have left women workers more vulnerable than ever to exploitation and abuse. The majority of workers laid off during the pandemic were women, and unions have been organizing to ensure women workers are at the bargaining table to win protections from employers, including access to childcare, adequate protective equipment and protections against GBVH at work. Unions in the agricultural sector are demanding that multinational companies do more to ensure greater safety on the job. Munguia discussed the power of union organizing, stressing that women in trade unions had the ability to speak out against mistreatment and come together to create solutions.

In Honduras, Munguía is part of a campaign for C190 ratification, while also training women to be part of negotiations with employers so they can advocate for contract clauses that benefit them, such as childcare and a violence-free workplace.

“We have a great advantage by being unionized,” she said. “Whenever we face discrimination, harassment, we can report it, denounce it, talk about it—and that opportunity is there because we are part of a union.”

‘We Have a Great Advantage: We Are in a Union’

UGTT’s Nadia Bergaoui shared images of women agricultural workers as she discussed the challenges they face at work.

In the face of such challenges, women have stepped up their efforts to achieve justice at the workplace, according to the panelists, including efforts to push their governments to ratify Convention 190. Adopted by the International Labor Organization in 2019, the convention seeks to end violence and harassment in the world of work, including gender-based violence.

Across Tunisia, where 500,000 women work in the informal agricultural sector, the Federation of Agriculture and the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT) are working to end gender-based violence through awareness-raising programs that ensure women know their rights on the job and can speak out for safe conditions, especially on the dangerous transport to and from work, said Nadia Bergaoui.

Bergaoui, general secretary, media officer and women’s affairs officer of the Federation of Agriculture, said a union survey in 2020 found that more than half of women said they have faced verbal or physical abuse on the job, and lack access to paid time off, sick leave or health care. The union is organizing workers to demand safe transportation, protections against GBVH, PPE and access to social protections.

Unions in Kyrgyzstan are advocating for protections for women workers, says Gulnara Derbisheva.

Gulnara Derbisheva, director of Insan Leilek, discussed how unions in Kyrgyzstan are advocating for protections for women workers, including demanding that the government address the increase in GBVH during the pandemic by ratifying Convention 190. Unions, with Solidarity Center support, opened a women migrant worker center in Bishkek, where workers have reported increases in GBVH and other abuse on the job. She shared how she is working with unions to advocate for greater protections for women migrant workers, including ratification of C190.

“Unless we keep advocating, we will be in a standstill,” she said.

Watch a recording of the event, simultaneously translated for Arabic, English, Khmer, Russian and Spanish speakers.

Jan 27, 2021

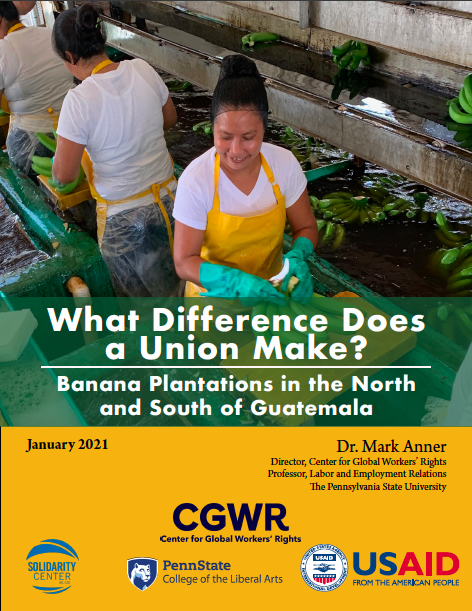

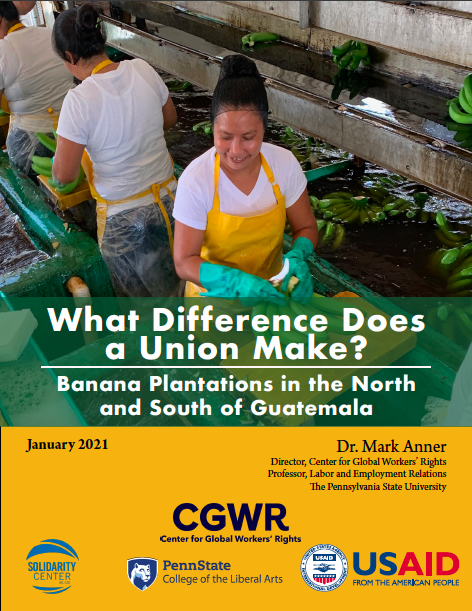

Guatemalan banana workers without a union work longer hours and earn less than half than of those who are unionized, and report more cases of verbal and physical abuse.

Download in English.

Download in Spanish.

Jan 11, 2021

In an historic judgment, the South African Constitutional Court in mid-November recognized that injury and illness arising from work as a domestic worker in a private home is no different to that occurring in other workplaces and equally deserving of compensation. Beyond recognizing occupational hazards in the home, the decision also recognized the broader harm wrought by the invisibility of gendered, racialized work in the privacy of homes in the context of post-colonial and post-apartheid South Africa.

In the case of Mahlangu and Another v Minister of Labor and Others, the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union (SADSAWU), with support from the Solidarity Center, challenged the constitutionality of provisions of the Compensation for Occupational Injury and Illness Act (COIDA), which precludes domestic workers employed in private homes from making claims to the Compensation Fund in cases of illness, injury, disablement or death at work. The Constitutional Court agreed that this exclusion violates rights to social security, equality and dignity, and it made this finding retroactively applicable from 1994, the date the South African constitution was enacted. In so doing, the court articulated a theory of intersectional discrimination and moved forward its own jurisprudence on indirect discrimination, infusing the right to social security, dignity and retrospective application with an intersectional analysis. It also reframed the narrative on domestic workers: no longer invisible but “unsung heroines in this country and globally”(paragraph 1).

The judgment gives a central role to international law, and establishes that “in assessing discrimination against a group or class of women of this magnitude that a broad national and international approach be adopted in the discourse affecting domestic workers“(Paragraph 42). It continues that, under international law conventions, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the exclusion of domestic workers from COIDA is inexplicable.

The court found that COIDA is a form of social security because the inability to work or the loss of a breadwinner’s support as a result of the COIDA exclusion, traps domestic workers and their dependents in cycles of poverty. According to the court this exclusion is unreasonable because it did not take into account the needs of the most vulnerable members of society, particularly those who experience compounded vulnerabilities arising from intersecting maltreatment based on race, sex, gender and/or class. It concludes that there is no legitimate objective to the exclusion, rather it entrenches patterns of disadvantage.

This case could be easily disposed on grounds of direct discrimination, since the majority found the exclusion irrational and arbitrary, and therefore constitutionally invalid. However, the case provided the court with a unique opportunity to interpret constitutional provisions on indirect discrimination, using an intersectional framework: Domestic workers “are predominantly Black women … and discrimination against them constitutes indirect discrimination on the basis of race, sex and gender” (paragraph 75). It goes on to find that discrimination on the grounds of race, gender and sex are not only presumptively unfair “but the level of discrimination is aggravated”(paragraph 73).

The court took the opportunity to enunciate a theory of intersectionality, which considers the social structures that shape the experience of marginalization, and the convergence of sexism, racism and class stratification. Viewed historically, the racial hierarchy established by apartheid, placed Black women at the bottom of the social hierarchy and relegated them to low-skilled and low-paid sectors of the workforce, such as domestic work. This sector was and is predominated by Black women and remains the third largest employer of women in South Africa. Yet it continues to be characterized by poverty-level salaries and poor living conditions, in which domestic workers are deprived of their own family while caring for that of their employers. As a result, the court found that domestic workers are a “critically vulnerable group of workers,” declaring the COIDA exclusion invalid both at an individual and group level (paragraph 106).

Background

The case centers on Maria Mahlangu, who was employed as a domestic worker in a private house for 22 years. According to her family, she was partially blind and could not swim. In March 2012 while at work, she fell into her employer’s swimming pool and drowned. When Mahlangu’s dependent daughter approached the Department of Labor for compensation, she was told that she was precluded from doing so under COIDA. Then SADSAWU organizer Pinky Mashiane read about the incident in a newspaper and approached the family to see how she could assist.

In 2013, the Solidarity Center embarked on a research project under a USAID grant to examine domestic workers’ socioeconomic rights in South Africa, which culminated in a list of domestic worker issues requiring urgent law reform. At the top of this list was inclusion of domestic workers in COIDA. Indeed, the issue had been on the agenda since 2001, without legislative reform being passed.

At the same time the Solidarity Center was looking for a litigant to challenge COIDA’s constitutionality. Pinky Mashiane—after having been turned down by multiple lawyers and law centers—was looking for a remedy to assist Mahlangu’s family. The Solidarity Center approached lawyers in South Africa as well as SADSAWU leadership with the proposal to litigate this case in constitutional terms, with financial support. Beginning in 2015, the case wound its way through the South African court system, litigated before the Constitutional Court by lawyers from the Social and Economic Rights Institute (SERI).

The case benefited from sustained advocacy at global and local levels. In 2019 , the Solidarity Center and partners brought the issue of domestic workers’ exclusion from COIDA before the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which was considering South Africa’s compliance with treaty obligations. In its concluding observations, cited in the Constitutional Court’s decision, the Committee recommended that South Africa include domestic workers in COIDA. Similarly, in the early stages of litigation, the amicus, the Gender Commission of South Africa, expressed frustration at the almost complete absence of information on the types of injuries and illnesses arising in the context of domestic work in private homes. To fill this vacuum, Solidarity Center commissioned qualitative research consisting of in-depth interviews with domestic workers around the country, describing the types of injury and illness occurring in the context of the home. After the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, which had severe consequences for domestic workers, domestic worker unions and partners also put together a petition to try and propel the legislature to include domestic workers in COIDA. Most significantly, at each of the numerous court hearings, the domestic worker unions and groups maintained a constant presence at the court, and in the media, insisting that the death of Maria Mahlangu not be in vain.

Far-Reaching Impact

When Solidarity Center initially proposed constitutional impact litigation on COIDA, it was with the hope that a successful outcome in this case would serve three purposes: obtain much-needed relief for domestic workers who were outside of COIDA’s purview; strengthen domestic worker unions; and create an important precedent that would lay the foundation for jurisprudence on domestic workers that could serve as a global marker.

The Mahlangu decision will clearly achieve the first as it removes the legal obstacle to domestic workers claiming compensation, with immediate and retrospective effect. Meanwhile, the long road to Mahlangu has also strengthened a growing coalition of unions and NGOs that have articulated their claims effectively in all forms of media. The fact that after 26 years of democracy, Mahlangu is the first case brought by the domestic worker union to the apex court of South Africa and guardian of constitutional values is a significant milestone.

Yet, perhaps the greatest import of Mahlangu might lie both in its precedent and in the paradigm it establishes to conceptualize domestic work. Using international human rights norms as a reference point, the court sets up an approach on domestic workers as a category, which stands to benefit domestic workers in South Africa and beyond. It also reasserts the goals of transformative constitutionalism as “undoing gendered and racialized poverty” and insists that an intersectional and historic lens is essential to the achievement of structural and systematic transformation. Indeed, the adoption of a historical lens allows the Court to reframe the narrative of domestic workers and their place in South Africa’s constitutional democracy: no longer powerless and invisible, but foundational toSouth Africa’s constitutional project. This reframing is captured eloquently in the concurring judgment of Justice Mhlantla who asserts that these Black women are smart, creative and survivors; who frequently work in environments that are emotionally and physically challenging, and which carry vestiges of South Africa’s colonial and apartheid past. She concludes: “On the contrary, they have a voice,” and according to Justice Mhlanthla J (paragraph 195) as well as the substance of majority judgment, the Constitutional Court is “listening.”

Oct 21, 2020

Even as gender equality and women’s fundamental rights are under attack around the world, women activists and their unions and organizations are standing up to the challenges and pushing back, panelists said yesterday during the launch of a landmark report, “Celebrating Women in Civil Society and Activism” with Clément Voule, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association.

“Women around the world are building economic power by exercising freedom of association and assembly,” said Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau. “Unions and the right to collective bargaining is one way we fight back.” (Watch the event here.)

“Courageous women and organizations are pushing back,” said Bahia Tahzib-Lie, Netherlands Ambassador for Human Rights in her opening remarks. “They make clear that women’s voices can no longer be ignored or silenced.”

“Courageous women and organizations are pushing back,” said Bahia Tahzib-Lie, Netherlands Ambassador for Human Rights in her opening remarks. “They make clear that women’s voices can no longer be ignored or silenced.”

The virtual side event, co-sponsored by the Solidarity Center, brought together women civil society leaders from around the world to discuss the findings of the report, prepared by Voule, who is presenting the report to the UN General Assembly this week.

“Women’s organizations and movements and their contribution to activism and civil society continued to be undervalued,” Voule said, highlighting one of the report’s key findings. Their ability to freely form unions and associate is key to their ability to create positive change, according to the report. Yet these rights increasingly are being violated, he said.

“Women are 50 percent of the population” but are often targeted by harassment and other forms of violence when they seek to form unions to improve their workplaces, he said, one of the report’s many findings informed by the experiences of many Solidarity Center partners.

Gender-Based Violence Undermining Women’s Basic Rights

“All forms of gender-based violence and harassment must end,” says UN Special Rapporteur Clément Voule.

Crucially, the report finds that gender-based violence and harassment (GBVH) is “perhaps the fiercest form of reprisal to the exercise of the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association for women workers.”

Gender-based violence begins at home for women and continues to all aspects of public space: “to the streets and the workplace and the public sphere,” said Voule, and COVID-19 lockdowns have worsened the violence women face at home.

The pandemic also has increased the violence women face at work, said Bader-Blau. But a new treaty the International Labor Organization approved last year creates the fundamental right to be free from violence and harassment at work by addressing the root causes of gender-based violence which often also involve race, ethnicity and gender identity.

The treaty, Convention 190, “demands employers and governments make real changes,” she said. “The treaty calls for employers to negotiate directly with workers. No longer can we look at workplace as the private sphere of the employer where workers give up their rights.”

Unions and the right to collective bargaining is one way we fight back”—Shawna Bader-Blau.

Unions and other activists are campaigning for their governments to ratify C190, a difficult process, but one that creates the opportunity for coalition building and cross-movement building among unions, feminist organizations and our allies, said Bader-Blau.

Voule also pointed out how the pandemic has been used to limit the space for civil society, with women especially targeted. “COVID-19 has increased criminalization of women’s rights organizations and harassment against women exercising their rights to peaceful assembly and association with worrisome reports on the misuse of emergency measures, application of criminal laws or limiting public gatherings.”

Progress, Challenges from Beijing +25

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women and UN adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action on advancing women’s rights, a landmark panelists said should be celebrated, but also reinforced and built upon.

World leaders are now talking about gender equality, but only due to the efforts of grassroots women activists, says Nicolette Naylor.

“Over the last 25 years, we have gone from zero laws, zero resolutions to over 120 laws and resolutions to protect gender equality,” said Nicolette Naylor at the Ford Foundation. “It shows us that progress is possible. This is thanks to women on the ground pushing for change. It’s because of the mobilization of women’s rights organizations and feminists on the ground.”

Making progress on ending gender inequality means involving women and ensuring their voices are heard, according to panelists who reinforced the report’s recommendations that “effective strategies to address violations of women’s rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association should be grounded in supporting and empowering women’s movements and organizations in all their diversity.”

“Many women on the ground led the way. Now we need to create more space for women to get places they deserve so they can push forward these agendas,” said Mireille Tushiminina from the Cameroon Women’s Peace Movement. “To hold our governments accountable, we need to be part of the conversation. Women are at the forefront and need to be in the conversation.”

Uma Mishra-Newbery at the Women’s March Global moderated the panel, which also included Marusia López from the Mesoamerican Network of Women Human Rights Defenders and Masina Fusi at Her Voice.

Event co-sponsors included Access Now, CIVICUS, Freedom House, Geneva Academy, Iniciativa Mesoamericana de Mujeres Defensoras de Derechos Humanos, International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, Women’s Global March, Women’s Major Group and the World Movement for Democracy.

“Courageous women and organizations are pushing back,” said Bahia Tahzib-Lie, Netherlands Ambassador for Human Rights in her opening remarks. “They make clear that women’s voices can no longer be ignored or silenced.”

“Courageous women and organizations are pushing back,” said Bahia Tahzib-Lie, Netherlands Ambassador for Human Rights in her opening remarks. “They make clear that women’s voices can no longer be ignored or silenced.”