Apr 9, 2018

Five years after the deadly Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh, workers and union activists say despite the massive demand from workers for union representation to achieve safe workplaces, worker-organizers must face down threats, harassment and violence to educate workers about their rights on the job.

Shamima Aktar is among Bangladesh garment worker-organizers empowering workers. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mugfiq Tajwar

Since the April 24, 2013, tragedy in which more than 1,130 garment workers died and thousands were injured, the government has approved a little more than half of the garment unions that have applied for official registration, according to Solidarity Center data. Confronted with employers and a government hostile to worker organizations, worker-organizers have sometimes risked their lives to help workers improve wages and working conditions.

Shamima Aktar, a garment factory worker and organizer with Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF), is one of them. During a meeting with management at a newly unionized factory, managers refused to grant a demand made by the factory union that salaries be paid on a timely basis. Instead, Shamima and the other union representatives were locked in the building and beaten, she says.

“But what moved me was that hearing about our abuse, 17 trade unions around the community immediately came to our aid and barricaded the whole factory which we were in. The workers needed us on their side to be able to live in peace and I wish to [keep organizing] no matter how difficult it is for me,” she says.

Through persistence and courage in the face of daunting odds, worker-organizers have helped garment workers form unions despite the severe obstacles. In Bangladesh, more than 200,000 garment workers at 445 factories are represented by unions that protect their rights on the job.

“I have worked day and night, went to gates of factories to talk to the workers, walked with them to their homes to earn their trust and to make them aware of how they are being exploited and deprived of their rights,” says Monira Aktar, an organizer with the Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation (BIGUF). “So far, we have united 2,250 workers into trade unions, and they say that we give them courage and hope. For me, these words are enough to encourage me to work on for them.”

Poverty Wages, Safety Improvements

Thousands of garment workers have participated in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. Credit: Solidarity Center/Rakibul Hasan

Wages in Bangladesh are the lowest among major garment-manufacturing nations, even though the cost of living in Dhaka is equivalent to that of Luxembourg and Montreal. The country’s labor law falls far short of international standards, and the Bangladesh government has failed to enact meaningful legal reforms, including addressing the arbitrary union registration process that is vulnerable to employer manipulation. Without a union, garment workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions.

But due to international action after the Rana Plaza disaster, which occurred months after a deadly fire at Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory killed 112 mostly female garment workers, a variety of efforts to prevent unnecessary deaths and injuries due to fire or structural failures—including the Bangladesh Accord on Building and Fire Safety—have remedied dangers at more than 1,600 factories.

The Solidarity Center has trained more than 6,000 union leaders and workers in fire safety, helping to empower factory-floor–level workers to monitor for hazardous working conditions and demand safety violations be corrected.

Such international attention has opened up space for workers to collectively demand—and win—improvements on the job, says Monira.

“I am proud that we have been able to create leaders among the workers by organizing them into trade unions. In the past this would have been close to impossible.”

In Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center implements the Workers’ Empowerment Program – Components 1 and 2, which provides training and rights education to garment workers and organizers, with the support of USAID.

Iztiak, an intern in the Solidarity Center Bangladesh office, interviewed the worker-organizers in Dhaka.

Apr 5, 2018

I am Khadiza Akhter, vice president of the Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF), where I have worked since 2008.

I started to work in a garment factory at a very young age. My family was poor, so I did not have the luxury to continue my education. One day I came to know about a federation (BIGUF) which was led by women. As women leaders were rare I went to attend one of the sessions of that federation. There, for the first time, I heard about labor law.

Factories did not follow Bangladeshi labor law. When I tried to raise voice against malpractices, my supervisors threatened my job. Our factory did not have an active union so I could not take any legal action against such abuse, but I received training in labor law from my federation. Eventually I was blacklisted in the garment sector for my union work, but BIGUF offered me a job and I worked there for six years as an organizer.

In 2008, I joined Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF). And I did try to unite workers to form an active union for a factory in Dhaka, but the government rejected the registration of the union.

The Rana Plaza disaster changed perspectives. The entire working community realized that same kind of disaster could have happened to them, so they became more focused on a safe working environment. Many workers came to Ashulia to protest.

SGSF started to work with union members to identify unsafe buildings. Our trained organizers conducted fire and safety training for educating general members. They were interested to come to our training so that they could understand legal requirements for ensuring the safety of the factories.

The Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh (the Accord) and the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety (the Alliance) contributed to ensuring the safety of the factories but there is lots more work to be done. For instance, no routine or monthly check up is done in most factories. Additionally, fire extinguishers and other equipment are not maintained by the management. Here, almost all the safety committee exists only on paper. We are now working in this arena for maintaining the standard of fire safety. This is a big task in the future.

Nov 24, 2017

Four million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across Bangladesh, making the country’s $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China.

Wages are the lowest among major garment-manufacturing nations, while the cost of living in Dhaka is equivalent to that of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Luxembourg and Montreal.

The workers receive few or no benefits and often struggle to support their families. Many risk their lives to make a living.

On November 24, 2012, a massive fire tore through the Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing more than 110 garment workers and gravely injuring thousands more.

In the wake of this disaster, garment workers throughout Bangladesh are standing up for their rights to safe workplaces and living wages. With the Solidarity Center, which partners with unions and other organizations to educate workers about their rights on the job, garment workers are empowered with the tools they need to improve their workplaces together.

Learn more about the Solidarity Center’s work in the global garment industry

DISASTER STRIKES TAZREEN

Tahera Tahera cannot remember much about her life before the day she was trapped in the Tazreen fire. She is unable to care for her four-year-old son and rarely comes out of her room. “It seems to me that something dark comes to my door and is calling me,” she says. “When I see the darkness, I become unstable and want to go far away from here,” she said.

On November 24, 2012, women and men working overtime on the Tazreen production lines were trapped when fire broke out in the first-floor warehouse. Workers scrambled toward the roof, jumped from upper floors or were trampled by their panic-stricken co-workers. Some could not run fast enough and were lost to the flames and smoke.

Hundreds of those injured at Tazreen, like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often are unable to support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation.

Some 80 percent of export-oriented ready made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh need improvement in fire and electrical safety standards, despite a government finding most were safe, according to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

TAZREEN NOT UNIQUE

The Tazreen fire was not an isolated incident. Months after the Tazreen disaster, more than 1,000 garment workers were killed when the Rana Plaza building collapsed.

Approximately 2,500 people were injured—many of them losing limbs and thousands more severely traumatized.

Workers were forced to return to the building despite the warnings of structural engineers that the building was unsound.

On the five-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, women garment workers rally in Savar, Bangladesh with the relatives of those who died or were grievously injured. Credit: Solidarity Center/Musfiq Tajwar

FACTORIES CAN BE MADE SAFE

From November, 2012 to March, 2018, Bangladesh’s garment sector has suffered 3,875 injuries and 1,303 deaths due to fires, building collapses and other tragedies, according to data collected by the Solidarity Center.

The Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza collapse were preventable. Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace.

Without a union, garment workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions.

They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Unions have helped to improve these conditions.

A young woman protests garment worker deaths in Bangladesh. Credit: Solidarity Center/Sifat Sharmin Amita

WORKERS DEMAND CHANGE

Garment workers throughout Bangladesh have staged rallies to demand that multinational corporations respect their human rights.

Women rally for their rights with labor rights organization and Solidarity Center partner Awaj Foundation near the Dhaka Press Club on May 1, 2018. Credit: Solidarity Center/Musfiq Tajwar

They have joined together to form workplace unions and bargain for safe working conditions, better wages and respect on the job.

Credit: Solidarity Center

WORKERS STAND TOGETHER

When workers stand together, they can make their voices heard without fear.

The Solidarity Center partners with numerous unions and worker associations in Bangladesh. Credit: Solidarity Center

UNIONS SAVING LIVES

Worker voices have yielded real results.

Over the past few years, the Solidarity Center has held fire safety trainings for hundreds of garment factory workers.

Workers learn fire prevention measures, find out about safety equipment their factories should make available and get hands-on experience in extinguishing fires.

The Solidarity Center has also trained more than 6,000 union leaders and workers in fire safety, helping to empower factory-floor-level workers to monitor for hazardous

working conditions and demand safety violations be corrected.

Union leaders participate in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. Credit: Solidarity Center

Salma (below), a garment worker, and her co-workers faced stiff employer resistance when they sought to form a union.

With assistance from the Solidarity Center and the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF), to which their factory union is affiliated, workers negotiated a wage increase, maternity benefits and safe drinking water.

The factory now is clean, has adequate fire extinguishers on every floor, and a fire door has replaced a collapsible gate.

More than five years later, 445 factories with over 216,000 workers have unions to represent their interests and protect their rights.

Salma, a garment factory union leader in Bangladesh, says with a union, the factory is safer and workers have better wages. Credit: Solidarity Center

“CHANGES ARE POSSIBLE IF YOU HAVE UNION AND YOU CAN MAKE IT WORK.” – SALMA

Garment workers learn fire safety and other measures to improve their working conditions. Credit: Solidarity Center

INVISIBLE NO LONGER

When women workers form unions, they improve their working conditions. Through Solidarity Center workshops and leadership training, more women are running for union office.

Women now make up more than 61 percent of union leadership in newly formed factory level-unions.

As workers strengthen their collective voice in their workplaces and beyond, their hard work, their lives and their humanity become visible once more.

Bipasha, Quality Inspector (bottom left). Rina, Operator (bottom right) . Ratan, Tailor (top right). Credit: Solidarity Center

Mahfuza, Assistant Operator (top right). Sharifa, General Operator (bottom right). Credit: Solidarity Center

To learn more about garment workers in global supply chains and how the Solidarity Center supports them, visit solidaritycenter.org.

Nov 9, 2017

In Honduras, union leaders are on their way to successfully negotiating eight collective bargaining agreements covering 21,000 garment workers who have joined unions in the past few years. Contracts negotiated so far include 23 percent wage increases, free transportation to and from work, free lunch, additional severance pay for workers recovering from ergonomic-related illnesses, and educational funds for workers and their children.

Five of those agreements will be first-ever pacts for 17,350 workers, says Evangelina Argüeta Chinchilla, coordinator of organizing maquila workers in the northern Choloma region for the General Workers Central (CGT) union confederation.

Argüeta Chinchilla, whose efforts to improve factory workplaces and whose training among women garment workers is enabling them to take leading roles in their unions and communities, will be honored along with the Honduran union movement November 15 at the Solidarity Center 20th Anniversary celebration in Washington, D.C.

The evening event features AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer Liz Shuler and also will honor U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown for his leadership to protect worker rights and the brave Colombian union and community activists for their frontline-efforts to achieve social justice in their country. And special guest U.S. Rep. Karen Bass will deliver remarks. (There’s still time to sponsor the event or buy tickets to attend!)

The day begins with a launch of the Solidarity Center-support book, Informal Workers and Collective Action: A Global Perspective, and panel discussions featuring U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal and international worker rights activists. (Find out more about the free book event and RSVP here.)

Honduran Unions ‘Persevere on Behalf of Workers and Their Families’

In a country where in recent years union leaders have been harassed, attacked and even murdered, and where employers utilize hardball tactics to prevent workers from forming unions and bargaining contracts, the stunning success of the garment workers in achieving fundamental workplace rights is a “testament to the determination of the Honduran union movement to persevere on behalf of workers and their families,” says Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau. “Together, they are helping to ensure that workers have living wages, just and fair workplaces and the opportunity to improve the future of their children.”

Argüeta Chinchilla is emblematic of these dedicated activists. She began work in a maquila at age 15, where she toiled for nine years and was a founder of the union at her factory before becoming a full-time organizer for the CGT. With Argueta’s leadership, Honduran garment-sector unions have negotiated historic worker rights agreements with two major U.S. clothing brands, Fruit of the Loom (2009) and Nike (2010), that laid the groundwork for successive organizing and collective bargaining achievements.

She and other women unionists hold leadership trainings with assistance from women’s rights organizations and the Solidarity Center. Argüeta Chinchilla hopes to see women “exercising power proportional to the numbers we represent in the world, in the labor movement.”

Empowered women now ensure their concerns are reflected in bargaining agreements. Some of the contracts garment workers have negotiated so far grant women who have just given birth additional paid leave beyond the 12-week maternity leave they receive under Honduran law.

“This is important, because a lot of times women workers must resign because they don’t have anyone to take care of their baby, especially in the early weeks, and this will help them get through that period,” says Argüeta Chinchilla, speaking through a translator.

Expanding Democracy Through the Freedom to Form Unions

International solidarity with Honduran workers has been key to furthering their efforts to achieve decent jobs. In November 2009, Russell Athletic agreed to rehire 1,200 workers in Honduras who lost their jobs when the company closed the factory in an attempt to bust the union, after the union—with support from the Solidarity Center and the United Students Against Sweatshops—convinced 110 U.S. universities to cut their apparel contracts with Russell.

Since then, says Argüeta Chinchilla, “it is very evident that significant protections have been made—workers are more educated about their rights, there is more respect for freedom of association and collective bargaining, and improvements such as health and safety for workers.

“There is always the fear of losing your job, but less now than what happened in past.”

Earlier this year, a four-year campaign by Honduran labor unions to improve workplaces and strengthen the rights of workers culminated with the Honduran National Congress approving a new labor inspection law. The law promotes, monitors and is designed to ensure that workplace standards, safety and health provisions, and social security requirements are upheld. It includes financial penalties for violations of worker rights, including the right to form unions.

Argüeta Chinchilla knows that such success begins through empowering workers, especially women workers, to take active roles in their unions.

“The internal democracy of unions has improved,” says Argüeta Chinchilla. “Many more women are active in union leadership, and this has translated into civil society: Workers are more participative in democracy and government and the country in general.”

May 22, 2017

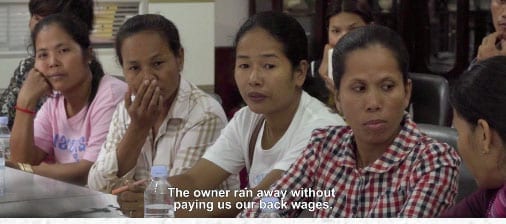

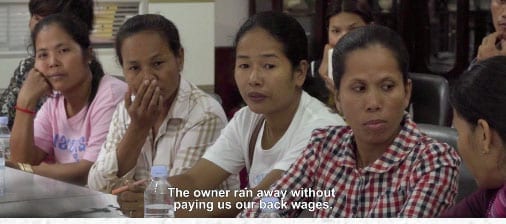

Knowing that conditions in garment factories around the world should be improved is not the same as seeing those workplaces firsthand and talking with garment workers about their daily experiences on the job, as three Parsons Design students found out when they traveled from New York City to Cambodia.

“Hearing their stories, and seeing that they are more than just a number, was something that was really eye-opening,” says Allison Griffin, a dual fashion-journalism major who took part in a video project by Re/Make, a U.S.-based non-profit organization focused on ethical production of clothes and other other garments.

Griffin, Casey Barber and Anh Le, all of whom graduated last week, met last fall with garment workers like the woman who described the high penalty she faces for making a mistake when assembling garments.

“If there are 12 pieces and I forget to put a code on one piece, they don’t pay me for any of them,” she says. “I get nothing for that day.”

She is among some of the more than 200 women whose employer last July abruptly closed the knitwear plant where some of them had worked for up to 18 years, leaving the workers without jobs or the more than $500,000 in compensation owed them.

Low Wages, Unsafe Conditions for Workers in Global Supply Chain

The tragedy of their story goes beyond a single knitwear plant in Phnom Penh. Workers throughout the global supply chain that fuels multinational corporations often face poverty wages, dangerous and unsafe working conditions, eroding rights on the job—and employers who find it all-too easy to abandon a plant in one country, only to open another elsewhere.

The students also met Sreyneang, a garment worker who invited the students to her home, where they met her two daughters whom she is supporting because her husband is unable to work.

“Every day when I finish my work (at one factory), I have to work at other factories until 9 or 10 p.m.,” says Sreyneang. “I walk home late.”

Sreyneang expressed hope the video can help improve the working conditions of Cambodia’s garment workers.

“It’s a lot to handle,” says Barber, speaking through tears on the video. “But hopefully we can make people understand and make change.”