Apr 7, 2021

As a trans domestic worker from Nicaragua working in Guatemala, Francia Blanco says her experiences with verbal and physical abuse, discrimination, and forced labor conditions led her to take action to build a world where trans domestic workers had rights, respect and dignity on the job. And, back in Nicaragua, that’s exactly what she and her co-workers are doing through SITRADOVTRANS, a union of trans domestic workers that is breaking barriers in the labor movement and beyond.

“We all know that at times, results can be slow to appear but we always are training up more of our members to not only learn more themselves but also find more women in the community who want to be part of this process,” she says.

“And it’s an ongoing process because you know we live in a globalized world and things are always changing so this is not something that can stop, we always have to be moving with it.”

Blanco spoke with Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau in this week’s episode of The Solidarity Center Podcast.

Blanco’s union is a member of FETRADOMOV, the federation of domestic workers in Nicaragua.

“For us as a trans union, it is very important to affiliate with unions on the national level. We have more support when we are in greater numbers. And also, we are domestic workers. Most trans women see domestic work as one of the few options they have access to.”

Listen Anytime to The Solidarity Center Podcast!

The Solidarity Center Podcast, “Billions of Us, One Just Future,” highlights conversations with workers (and other smart people) worldwide shaping the workplace for the better.

Look for upcoming episodes, including:

April 14: Adriana Paz, an advocate with the International Domestic Workers Federation who understands firsthand the power of unions in ensuring domestic workers have safe, decent jobs

April 21: International Trade Union Confederation President Ayuba Wabba, who explores the Nigerian labor movement’s response to the COVID crisis on workers and discusses the global labor movement’s plans to build back better for workers around the world

And check out recent episodes:

- Winning Rights for Migrant Workers

- Defending Democracy: Workers on the Frontline

- Ending Gender-Based Violence at Work: The Campaign to Ratify ILO C190

This podcast was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement No.AID-OAA-L-16-00001 and the opinions expressed herein are those of the participant(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID/USG.

Jan 11, 2021

In an historic judgment, the South African Constitutional Court in mid-November recognized that injury and illness arising from work as a domestic worker in a private home is no different to that occurring in other workplaces and equally deserving of compensation. Beyond recognizing occupational hazards in the home, the decision also recognized the broader harm wrought by the invisibility of gendered, racialized work in the privacy of homes in the context of post-colonial and post-apartheid South Africa.

In the case of Mahlangu and Another v Minister of Labor and Others, the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union (SADSAWU), with support from the Solidarity Center, challenged the constitutionality of provisions of the Compensation for Occupational Injury and Illness Act (COIDA), which precludes domestic workers employed in private homes from making claims to the Compensation Fund in cases of illness, injury, disablement or death at work. The Constitutional Court agreed that this exclusion violates rights to social security, equality and dignity, and it made this finding retroactively applicable from 1994, the date the South African constitution was enacted. In so doing, the court articulated a theory of intersectional discrimination and moved forward its own jurisprudence on indirect discrimination, infusing the right to social security, dignity and retrospective application with an intersectional analysis. It also reframed the narrative on domestic workers: no longer invisible but “unsung heroines in this country and globally”(paragraph 1).

The judgment gives a central role to international law, and establishes that “in assessing discrimination against a group or class of women of this magnitude that a broad national and international approach be adopted in the discourse affecting domestic workers“(Paragraph 42). It continues that, under international law conventions, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the exclusion of domestic workers from COIDA is inexplicable.

The court found that COIDA is a form of social security because the inability to work or the loss of a breadwinner’s support as a result of the COIDA exclusion, traps domestic workers and their dependents in cycles of poverty. According to the court this exclusion is unreasonable because it did not take into account the needs of the most vulnerable members of society, particularly those who experience compounded vulnerabilities arising from intersecting maltreatment based on race, sex, gender and/or class. It concludes that there is no legitimate objective to the exclusion, rather it entrenches patterns of disadvantage.

This case could be easily disposed on grounds of direct discrimination, since the majority found the exclusion irrational and arbitrary, and therefore constitutionally invalid. However, the case provided the court with a unique opportunity to interpret constitutional provisions on indirect discrimination, using an intersectional framework: Domestic workers “are predominantly Black women … and discrimination against them constitutes indirect discrimination on the basis of race, sex and gender” (paragraph 75). It goes on to find that discrimination on the grounds of race, gender and sex are not only presumptively unfair “but the level of discrimination is aggravated”(paragraph 73).

The court took the opportunity to enunciate a theory of intersectionality, which considers the social structures that shape the experience of marginalization, and the convergence of sexism, racism and class stratification. Viewed historically, the racial hierarchy established by apartheid, placed Black women at the bottom of the social hierarchy and relegated them to low-skilled and low-paid sectors of the workforce, such as domestic work. This sector was and is predominated by Black women and remains the third largest employer of women in South Africa. Yet it continues to be characterized by poverty-level salaries and poor living conditions, in which domestic workers are deprived of their own family while caring for that of their employers. As a result, the court found that domestic workers are a “critically vulnerable group of workers,” declaring the COIDA exclusion invalid both at an individual and group level (paragraph 106).

Background

The case centers on Maria Mahlangu, who was employed as a domestic worker in a private house for 22 years. According to her family, she was partially blind and could not swim. In March 2012 while at work, she fell into her employer’s swimming pool and drowned. When Mahlangu’s dependent daughter approached the Department of Labor for compensation, she was told that she was precluded from doing so under COIDA. Then SADSAWU organizer Pinky Mashiane read about the incident in a newspaper and approached the family to see how she could assist.

In 2013, the Solidarity Center embarked on a research project under a USAID grant to examine domestic workers’ socioeconomic rights in South Africa, which culminated in a list of domestic worker issues requiring urgent law reform. At the top of this list was inclusion of domestic workers in COIDA. Indeed, the issue had been on the agenda since 2001, without legislative reform being passed.

At the same time the Solidarity Center was looking for a litigant to challenge COIDA’s constitutionality. Pinky Mashiane—after having been turned down by multiple lawyers and law centers—was looking for a remedy to assist Mahlangu’s family. The Solidarity Center approached lawyers in South Africa as well as SADSAWU leadership with the proposal to litigate this case in constitutional terms, with financial support. Beginning in 2015, the case wound its way through the South African court system, litigated before the Constitutional Court by lawyers from the Social and Economic Rights Institute (SERI).

The case benefited from sustained advocacy at global and local levels. In 2019 , the Solidarity Center and partners brought the issue of domestic workers’ exclusion from COIDA before the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which was considering South Africa’s compliance with treaty obligations. In its concluding observations, cited in the Constitutional Court’s decision, the Committee recommended that South Africa include domestic workers in COIDA. Similarly, in the early stages of litigation, the amicus, the Gender Commission of South Africa, expressed frustration at the almost complete absence of information on the types of injuries and illnesses arising in the context of domestic work in private homes. To fill this vacuum, Solidarity Center commissioned qualitative research consisting of in-depth interviews with domestic workers around the country, describing the types of injury and illness occurring in the context of the home. After the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, which had severe consequences for domestic workers, domestic worker unions and partners also put together a petition to try and propel the legislature to include domestic workers in COIDA. Most significantly, at each of the numerous court hearings, the domestic worker unions and groups maintained a constant presence at the court, and in the media, insisting that the death of Maria Mahlangu not be in vain.

Far-Reaching Impact

When Solidarity Center initially proposed constitutional impact litigation on COIDA, it was with the hope that a successful outcome in this case would serve three purposes: obtain much-needed relief for domestic workers who were outside of COIDA’s purview; strengthen domestic worker unions; and create an important precedent that would lay the foundation for jurisprudence on domestic workers that could serve as a global marker.

The Mahlangu decision will clearly achieve the first as it removes the legal obstacle to domestic workers claiming compensation, with immediate and retrospective effect. Meanwhile, the long road to Mahlangu has also strengthened a growing coalition of unions and NGOs that have articulated their claims effectively in all forms of media. The fact that after 26 years of democracy, Mahlangu is the first case brought by the domestic worker union to the apex court of South Africa and guardian of constitutional values is a significant milestone.

Yet, perhaps the greatest import of Mahlangu might lie both in its precedent and in the paradigm it establishes to conceptualize domestic work. Using international human rights norms as a reference point, the court sets up an approach on domestic workers as a category, which stands to benefit domestic workers in South Africa and beyond. It also reasserts the goals of transformative constitutionalism as “undoing gendered and racialized poverty” and insists that an intersectional and historic lens is essential to the achievement of structural and systematic transformation. Indeed, the adoption of a historical lens allows the Court to reframe the narrative of domestic workers and their place in South Africa’s constitutional democracy: no longer powerless and invisible, but foundational toSouth Africa’s constitutional project. This reframing is captured eloquently in the concurring judgment of Justice Mhlantla who asserts that these Black women are smart, creative and survivors; who frequently work in environments that are emotionally and physically challenging, and which carry vestiges of South Africa’s colonial and apartheid past. She concludes: “On the contrary, they have a voice,” and according to Justice Mhlanthla J (paragraph 195) as well as the substance of majority judgment, the Constitutional Court is “listening.”

Jul 24, 2020

Neha Misra, senior migration specialist for the Solidarity Center, said lack of freedom of association for migrant workers is leading to wage theft.

Jun 15, 2020

Domestic workers—at great risk during the pandemic crisis—are mobilizing to secure rapid relief and protection says the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF). This International Domestic Workers Day, more than 60 million of the world’s estimated 67 million domestic workers, most of whom are women of color working in the informal economy, are facing the pandemic without the social supports and labor law protections afforded to workers in formal employment. And, during a period of heightened infection risk, tens of thousands of migrant domestic workers are being forced to live in their employers’ homes, housed in crowded detention camps or have been sent home where there are no jobs to sustain them or their families.

The health and economic risks to domestic workers during the pandemic and compulsory national lockdowns are high. At the margins of society in many countries, most domestic workers are excluded from national labor law protections that require employers to provide paid sick leave and mitigate workplace infection risks through provision of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and appropriate social-distancing measures. And, if they get sick, many domestic workers cannot access national health insurance schemes.

“Domestic workers are among those most exposed to the risks of contracting COVID-19. They use public transport, are in regular contact with others… and don’t have the option of working from home, especially daily maids,” says Brazil’s national union of domestic workers, FENETRAD.

Without adequate personal savings due to poverty wages, many domestic workers and their families are suffering food insecurity because of income interruption or job loss.

“We can’t have many domestic workers left out in the cold,” says Myrtle Witbooi, founding member and first president of IDWF, and general secretary of the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union (SADSAWU).

“Let us shout out to the world: We are workers!” she says.

Domestic workers have long shared their experiences with the Solidarity Center, detailing their long working hours, poverty wages and violence and sexual abuse. During the pandemic, additional sources of economic peril and health risks are being reported, including:

- In Mexico, where 2.2 million women are domestic workers, most of them are being dismissed without compensation. In a recent survey of domestic workers, the national domestic workers union SINACTRAHO found that 43 percent of those surveyed suffered a chronic condition like diabetes or hypertension, increasing their vulnerability to COVID-19.

- The United Domestic Workers of South Africa says their members report that some employers refused to pay wages during the country’s compulsory lockdown unless staff agreed to shelter in place with their employer, and that domestic workers who could not report to work were not paid.

- In Asia, women performing care work were excluded when countries launched COVID-19 responses and stimulus packages, says Oxfam.

- In the Latin American region, where millions of people who labor in informal jobs rely on each day’s income to meet that day’s needs, the pandemic lockdown is causing an economic and social crisis.

- Globally, unemployment has become as threatening as the virus itself for the world’s domestic workers, reported the ILO in May.

Meanwhile, migrant domestic workers—who often leave behind their own children to care for others to support their own families back home—are in peril. Some are being sent home without pay, some are subject to wage theft. Others are being quarantined by the thousands in dangerously crowded conditions or in lockdown in countries where they do not speak the language and have little access to health care, local pandemic relief or justice. For example:

- Thousands of Ethiopian domestic workers are stranded in Lebanon by the coronavirus crisis.

- At least one-third of the 75,000 migrant domestic in Jordan had lost their incomes and, in some cases, their jobs only one month into the pandemic.

- For millions of Asian and African migrant domestic workers in the Middle East, governments restrictions on movement to counter the spread of COVID-19 increased the risk of abuse, reports Human Rights Watch.

- Several Gulf states are demanding that India and other South Asian countries take back hundreds of thousands of their citizens. Some 22,900 people were repatriated from the UAE by late April, many without receiving wages for work already performed.

On June 16, International Domestic Workers Day, we honor the majority women who perform vital care work for others. Every day, and especially during the pandemic, the Solidarity Center is committed to supporting the organizations that are helping domestic workers attain safe and healthy workplaces, family-supporting wages, dignity on the job and greater equity at work and in their community.

“International Domestic Workers Day is a great opportunity to talk about power and resistance, and how we survive now and build tomorrow,” says Solidarity Center Executive Director, Shawna Bader-Blau, who applauds actions by all organizations dedicated to supporting and protecting domestic workers during the pandemic. These include:

- Domestic workers who are leaning into organizing and advocacy efforts during the pandemic, including in Peru, where they won the right to a minimum wage and written contracts by challenging the constitutionality of failing to implement the ILO domestic workers convention after ratification; in the Dominican Republic, where they mobilized to register 20,000 domestic workers into the social security system and lobbied for their inclusion in government aid, gaining new members in the process; in Brazil, where they successfully fought to remove domestic workers from the list of “essential workers” to limit their exposure to COVID-19 because of their limited safety net.

- In Bangladesh, BOMSA, a migrant rights nongovernmental organization (NGO), is creating and distributing COVID-19 awareness-raising leaflets specifically for migrant domestic workers returning to Bangladesh from abroad. Members are distributing soap, disinfectant and other cleaning supplies, and encouraging workers to maintain social distance. Another migrant rights NGO, WARBE-DF, is distributing COVID-19 awareness-raising leaflets to returned migrant workers and their communities. And as thousands of migrant workers return, the organization is engaging in local government coronavirus response committees to ensure inclusion of migrant-specific responses. Both are longtime Solidarity Center partners.

- Also in Bangladesh, in Konbari area—where garment workers who are internal migrants are not eligible for relief aid as it relies on voting lists for relief distribution—the local Solidarity Center-supported worker community center is connecting with local government officials and has provided nearly 200 names for relief, and is fielding more calls from internal migrant workers seeking assistance.

- In Brazil, which has more domestic workers than any other country—over 7 million—the National Federation of Domestic Workers (FENETRAD) and Themis (Gender, Justice and Human Rights) started a campaign calling for domestic workers to be suspended with pay while the risk of infection continues, or to be given the tools to protect against risk, including masks and hand-sanitizing gel.

- Also in Brazil, FENATRAD is providing legal and other advice by phone to domestic workers and delivering relief packages of food, medicines and protective gear, including masks, clothing, soap and hand sanitizer, to union members and their families.

- In the Dominican Republic, three organizations representing domestic workers successfully advocated with the Ministry of Labor for domestic workers’ to be included in the country’s COVID-19 relief program.

- In Mexico, to raise awareness and make the sector more visible, SINACTRAHO collected WhatsApp domestic worker audio messages about their experiences during the crisis for sharing on a podcast.

- The Alliance Against Violence & Harassment in Jordan, a Solidarity Center partner, is urging the government to grant assistance to migrant workers, who have little or no pay but cannot return to their country. The Domestic Workers’ Solidarity Network in Jordan shares information on COVID-19 and its impact on workers in multiple languages on its Facebook page

- The Kuwait Trade Union Federation urged the government to address the basic needs of Sri Lankan migrant workers, many of whom were domestic workers trapped in Kuwait after Sri Lanka closed its borders on March 19. Workers were eventually housed in 12 shelters while travel arrangements home were made.

- In Qatar, Solidarity Center partners Migrant-Rights.org and IDWF in April helped launch an SMS messaging service in 12 languages to provide tips to migrant domestic workers on COVID-19 and how to protect their rights.

- In South Africa—where many domestic workers suffer deaths and crippling injuries without compensation because they are excluded from the country’s occupational injuries and diseases act (“COIDA”), according to a recent Solidarity Center report—trade unions are demanding that employers provide their domestic workers with adequate PPE.

The Solidarity Center has joined its partners, the Women in Migration Network (WIMN) and a coalition led by the Migrant Forum in Asia, in urging governments and employers to uphold the rights of migrant workers, including migrant domestic workers.

Without urgent action to provide relief to workers in informal employment, including those providing domestic work, quarantine threatens to increase relative poverty levels in low-income countries by as much as 56 percentage points according to a new brief from the UN’s International Labor Organization (ILO).

Mar 6, 2020

Domestic workers in Honduras increasingly are exercising their rights on the job in the country, where they have few labor law protections and so are especially vulnerable to abuse. More than 100 workers recently joined SINTRAHO (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadoras del Hogar), National Domestic Workers Union, which in October became the first legally registered domestic worker union in Honduras.

Following eight months of outreach, education, training and organizing, domestic workers formed SINTRAHO to address their difficult working conditions. Most domestic workers are women and many live in their employers’ homes, where they often are subjected to sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence. As in many countries worldwide, Honduran law excludes domestic workers from mandated breaks, minimum wages and access to social security.

“In Honduras, there are more than 100,000 domestic workers, and we believe that the best way for us to be heard and recognized is to organize ourselves and fight for our rights as workers in a sector that has been hidden,” says Silma Perez, SINTRAHO president.

Recognizing that most domestic workers in urban centers are internal migrants from rural areas, often from marginalized indigenous communities, leaders of FESTAGRO, the agroindustrial union federation supporting SINTRAHO, say it is especially import to support these workers as they organize for improved conditions. FESTAGRO’s confederation, CUTH, and Solidarity Center, also provide support for the new union.

Global Movement for Domestic Worker Rights

Domestic workers in Honduras are part of a worldwide mobilization of domestic workers seeking their rights, forming unions and associations, and pushing for their governments to ratify International Labor Organization Domestic Workers Convention (No. 189). Convention 189 is a binding standard in which domestic workers are entitled to full labor rights, including those covering work hours, overtime pay, safety and health standards and paid leave.

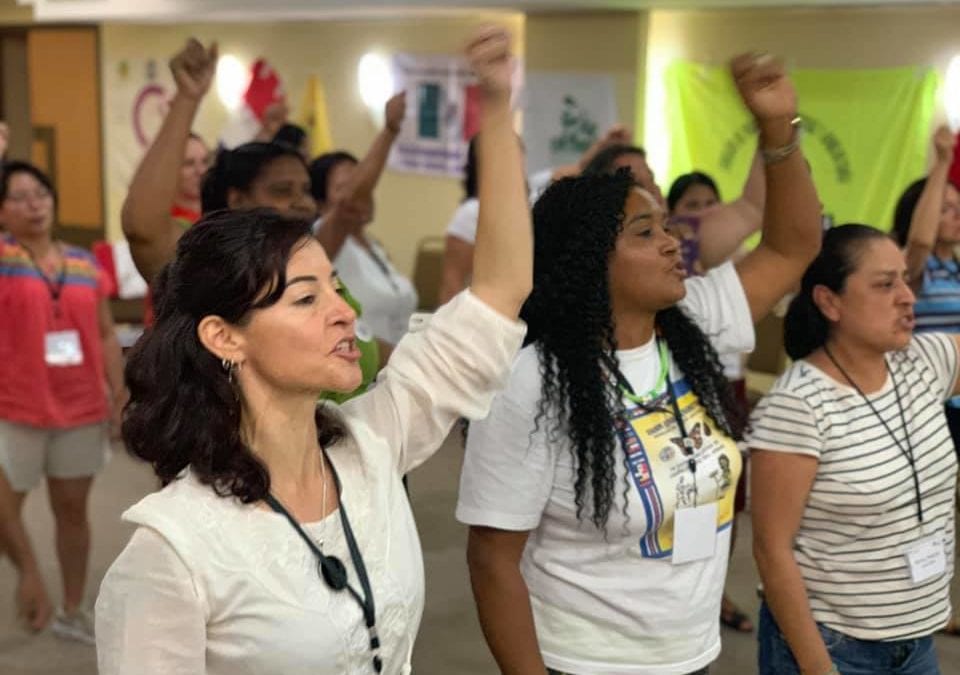

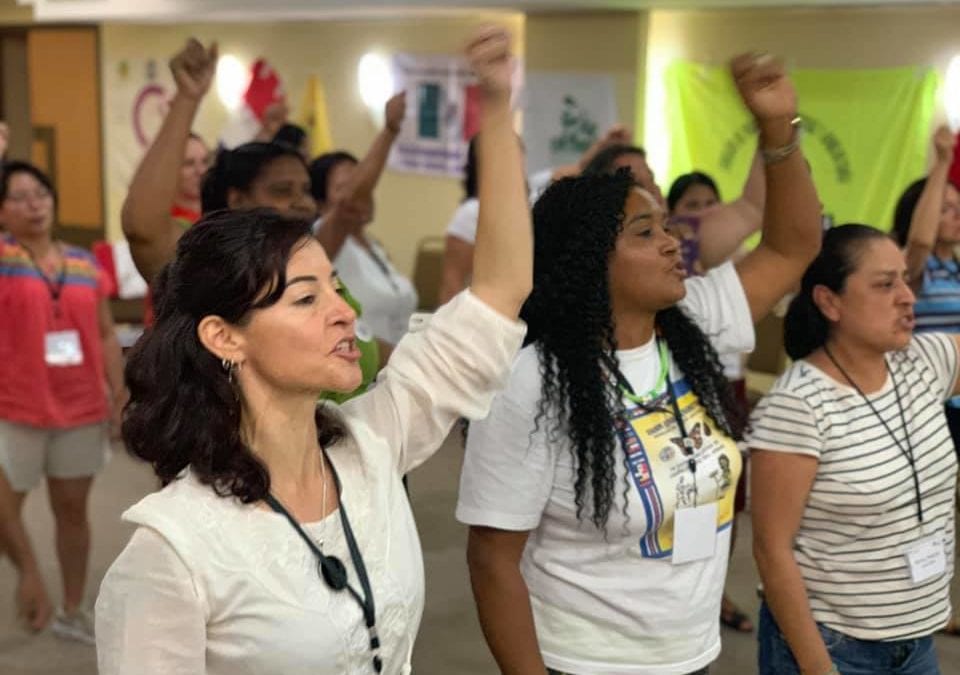

As tens of thousands domestic workers around the world mobilized around ILO 189, which was adopted in 2011, their efforts led to formation of the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF). Since then, domestic workers have campaigned for their governments to ratify it, and 29 countries have done so, meaning they are bound to its regulations, which include clearly stated work requirements, safe working conditions, paid annual leave and the freedom to form unions.

Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Panama are the only Central American countries that have ratified Convention 189, and SINTRAHO is planning a ratification campaign in Honduras. SINTRAHO also plans to push for greater protections for domestic workers under Honduran national labor law, including a fair minimum wage and access to social security protections.

SINTRAHO is the first national union in Honduras to specifically mention the rights of LGBTI workers in its statutes, and created an Executive Committee position for Secretary of Gender and Diversity to recognize and value its members’ diverse backgrounds.

“SINTRAHO will take on the challenge of organizing many more workers in the coming year in order to fight for national laws that will directly benefit us as domestic workers,” says Perez.