Jul 15, 2016

An astounding 80,000 Zimbabwe workers in formal employment—out of some 350,000 workers—did not receive wages and benefits on time in 2014, according to a new Solidarity Center report, “Working Without Pay: Wage Theft in Zimbabwe,” released today in Harare.

As a result of this widespread wage theft, many workers say they are forced to eat only one or two meals a day; move repeatedly to access affordable housing; and rent two rooms or fewer for their entire family to make ends meet.

As a result of this widespread wage theft, many workers say they are forced to eat only one or two meals a day; move repeatedly to access affordable housing; and rent two rooms or fewer for their entire family to make ends meet.

Through first-person interviews and other research by affiliates of the country’s main trade union confederation, the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU), the report provides hard data behind last week’s successful one-day shut-down of businesses, government and services by workers across Zimbabwe outraged over wage theft and a new law targeting market vendors who make up the vast proportion of the workforce.

Paid Only Enough to Get to Work

One woman interviewed in the report, whose experience is not uncommon, says she has received $26 a month in wages for the past eight months, although her monthly salary is $342. Yet basic living costs, which on average include $60 for renting a single room, $30 for electricity, $15 for water and $22 for transportation to work, mean she only has sufficient funds to get to and from her job.

“This failure to pay what workers are legally entitled to is wage theft in that it involves employers taking money that belongs to their employees and keeping it for themselves,” the report states. “This is a clear violation of international labor standards, as well as national legislation on the employment of workers.”

The report traces the ongoing wage theft to 2012, as employers in the public- and private-sector increasingly began delaying wage payments.

Up to 95% of Zimbabweans Work in Informal Economy

Simultaneously, the number of jobs in the informal economy has skyrocketed, the report points out. Some 6.3 million people made up Zimbabwe’s workforce in 2014, of which 5.9 million workers (94.5 percent) were informally employed, compared with 84.2 percent in 2011, according to “Working without Pay.” An additional 800,000 women and men were in the workforce, but unemployed.

Last month, the government introduced a statutory law that bans imports of basic commodities—a law that directly affects hundreds of thousands of informal economy workers who survive on cross-border trading. Up to 95 percent of jobs in Zimbabwe are in the informal economy, and workers say the new law takes away their livelihoods.

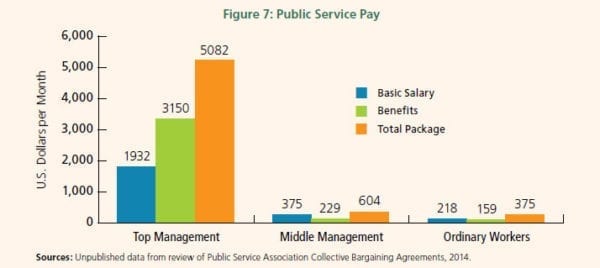

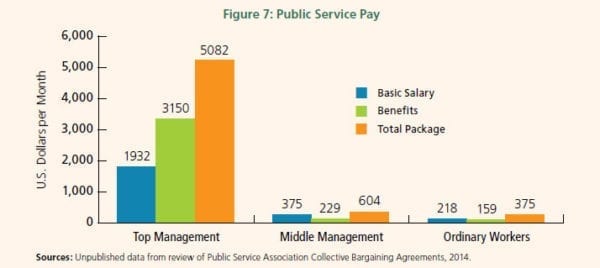

Based on surveys at 442 companies, and the result of extensive research by the Labor and Economic Development Research Institute of Zimbabwe, the report also documents extravagant salaries and benefits to middle and top management even as workers go unpaid and presents recommendations for action to address the problem.

Companies Involved in Wage Theft Must Be Held Accountable

Some of the recommendations include:

- The Ministry of Labor, together with representatives of employers and unions, should review the status of companies that are not paying their workers and assist in developing plans to rectify the injustice.

- Unions representing workers in companies not paying salaries—in full and on time—should demand that the government bring criminal proceedings under the relevant provisions of the Labor Act against employers.

- Trade unions should advocate for payment of interest on late payment.

- The government should set an example by reviewing the wage structure in government agencies and quasi-government agencies to limit benefits to top managers, institute a more just pay scale and prioritize payments to workers through collective bargaining or social dialogue.

Jul 8, 2016

An Uzbek victim of forced labor in cotton production and three human rights defenders filed a complaint against the World Bank’s private lending arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), according to a coalition of human rights groups.

The June 30 complaint seeks an investigation into forced labor connected to a $40 million loan to Indorama Kokand Textile, which operates in Uzbekistan. The forced labor victim, who requested confidentiality, and the rights defenders Dmitry Tikhonov, Elena Urlaeva and a third who requested confidentiality, presented evidence that the loan to expand the company’s cotton manufacturing facilities in Uzbekistan allows it to profit from forced labor and sell illicit goods.

“The IFC should support sustainable rural development in Uzbekistan, not projects that perpetuate the government’s forced-labor system for cotton production,” says Tikhonov, who lives is in exile in France following possible retaliation—including the burning of his home—for his efforts to document forced labor in Uzbekistan.

“The ombudsman should investigate the IFC loan to Indorama, which we believe violates international law and the IFC’s own policies prohibiting forced labor.” The Cotton Campaign, the Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights, the International Labor Rights Forum, and Human Rights Watch jointly announced the complaint.

1 Million in Forced Labor Each Year

Each year, the Uzbek government, which controls all of the country’s cotton production and sales, forces more than 1 million teachers, nurses and others to pick cotton for weeks. Last year, the government went to extreme measures—including jailing and physically abusing researchers independently monitoring the process—to cover up its actions.

Uzbekistan was downgraded to the lowest ranking in the U.S. State Department’s annual Trafficking in Persons report which was released last month.

The World Bank has invested more than $500 million in Uzbekistan’s agricultural sector. Following a complaint from Uzbek civil society, the bank attached loan covenants stipulating that the loans could be stopped and subject to repayment if forced or child labor was detected in project areas by monitors from the International Labor Organization (ILO), contracted by the World Bank to carry out labor monitoring during the harvest.

The World Bank approved the loan to Indorama in December 2015, despite an ILO report reaffirming the problem of forced labor.

In March, Cotton Campaign, a coalition of labor and human rights groups that includes the Solidarity Center, presented a petition signed by more than 140,000 people from around the world to World Bank President Dr. Jim Yong Kim, calling on the bank to suspend lending to the agriculture sector in Uzbekistan until the Uzbek government changes its policy of forced labor in the cotton industry.

Read the complaint here.

Jun 30, 2016

Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, two countries where forced labor in cotton harvests is rampant, have been downgraded to the lowest ranking in the U.S. State Department’s 2016 Trafficking in Persons Report released this morning. The report also downgraded Myanmar (Burma) but boosted the ranking of Thailand, which a coalition of labor and human rights groups says has not meaningfully addressed human trafficking and should not have been upgraded.

The report, which ranks countries based on their efforts to fight forced labor and human trafficking, downgraded Myanmar, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan to the lowest level (Tier 3), meaning their governments do not comply with minimum U.S. Trafficking Victims and Protection Act (TVPA) standards and are not making significant efforts to become compliant.

The report, which ranks countries based on their efforts to fight forced labor and human trafficking, downgraded Myanmar, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan to the lowest level (Tier 3), meaning their governments do not comply with minimum U.S. Trafficking Victims and Protection Act (TVPA) standards and are not making significant efforts to become compliant.

Each year, the Uzbek government forces more than 1 million teachers, nurses and others to pick cotton for weeks during last fall’s harvest. Last year, the government went to extreme measures—including jailing and physically abusing researchers independently monitoring the process—to cover up its actions.

In 2015, the State Department boosted Uzbekistan from Tier 3 to the “Tier 2 Watchlist,” saying the country was making efforts to become compliant with the TVPA, a move rejected by human rights activists who each year risk their lives to document widespread forced labor during cotton harvests.

Thailand Should Not Be Upgraded

Moving Thailand from the report’s lowest ranking is not warranted, according to a 13-member coalition, the Alliance to End Slavery and Trafficking (ATEST), which includes the Solidarity Center.

“Thailand’s lack of policy implementation and meaningful change on the ground calls for the lowest Tier 3 ranking,” says Kristen Abrams, ATEST acting director.

In June 2014, the State Department downgraded Thailand to the lowest ranking, due to reports of migrant workers, primarily from Burma and Cambodia, working in slave-like conditions on Thai fishing boats, fueling the country’s $7.3 billion seafood export industry and making it the world’s third-largest exporter. Today, many migrant workers still toil in forced labor and are held against their will on the boats where they are beaten and even killed. Thailand’s estimated 3 million migrants make up 10 percent of its workforce, but in seafood processing the make up 90 percent.

In releasing the report, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry highlighted the plight of domestic workers, many of whom are working in countries far from their homes and are especially vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Kerry announced the creation of a model contract for domestic workers based on international standards and a memorandum of understanding for origin and destination countries that sets clear standards designed to prevent the abuses of domestic work.

‘Malaysia Has Done Little to Address Trafficking’

This year’s report also fails to fix last year’s controversial upgrade of Malaysia, according to the coalition.

“More than a year after the discovery of mass graves of trafficking victims along the Malaysia-Thailand border, there is little evidence that Malaysia has taken anything more than meager steps to address its troublesome human trafficking situation,” Abrams says.

Among the 27 countries on Tier 3, the lowest ranking, are Algeria, Burundi, Haiti, Russia, Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

Profits from forced labor account for $150 billion per year, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

The report organizes countries into tiers based on trafficking records: Tier 1 for nations that meet minimum U.S. standards; Tier 2 for those making significant efforts to meet those standards; Tier 2 “Watch List” for those that deserve special scrutiny; and Tier 3 for countries that are not making significant efforts.

The Trafficking in Persons report, which has been issued annually for 16 years, covers 188 countries and is required by the 2000 TVPA law.

Jun 10, 2016

Workers’ rights were weakened in most regions over the past year, according to the 2016 International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) Global Rights Index.

Repression of worker rights was compounded by restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly, including severe crackdowns in some countries, which increased by 22 percent, with 50 out of 141 countries surveyed recording restrictions.

The ITUC Global Rights Index ranks 141 countries against 97 internationally recognized indicators to assess where workers’ rights are best protected, in law and in practice.

Global Rights Index Details Chilling Repression

- Unionists were murdered in 10 countries, including Chile, Colombia, Egypt, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Iran, Mexico, Peru, South Africa and Turkey.

- 82 countries exclude workers from labor law.

- More than two-thirds of countries have laws prohibiting some workers from striking.

- More than half of all countries deny some or all workers collective bargaining.

- Out of 141 countries, the number which deny or constrain free speech and freedom of assembly increased from 41 to 50.

- Out of 141 countries, the number in which workers are exposed to physical violence and threats increased by 44 percent (from 36 to 52) and include Colombia, Egypt, Guatemala, Indonesia and the Ukraine.

ITUC General Secretary Sharan Burrow summed up the global environment this way:

“Repression of workers’ rights goes hand in hand with increased government control over freedom of expression, assembly and other fundamental civil liberties, with too many governments seeking to consolidate their own power and frequently doing the bidding of big business, which often sees fundamental rights as incompatible with its quest for profit at any expense.”

Read the full report.

Jun 6, 2016

More than half of the workers at the eight Frito Lay worksites in the Dominican Republic who sought a voice on the job received official verification of their new union in recent days, culminating a process that began in April.

When the 621 sales, distribution and production workers joined the National Union of Workers of Dominican Frito Lay (SINTRALAYDO), their efforts were delayed by factory management, which questioned the eligibility status of dozens of workers.

Achieving union recognition by the international snack food company involved “all of the local union leaders” who “could recognize members missing from the company’s list and prove they worked there, preventing the company’s attempt to disqualify them from the count,” says SINTRALAYDO Secretary General Ramon Mosquea, a former Solidarity Center-supported labor educator.

Frito Lay Workers Persist over Years to Win Contract

The workers overcame huge obstacles to win a union. After they sought to achieve majority recognition for a union at the company in 2012, management derailed the process by presenting a list of hundreds of workers the union understood were sub-contracted, thereby reducing support for the union to less than 50 percent, according to SINTRALAYDO leaders. Dominican law requires that more than 50 percent of eligible workers support a union at a worksite before it can be officially recognized.

Since then, the company fired more than 500 SINTRALAYDO members, but workers persisted, joining with the union to recruit supporters, develop greater leadership among its executive committee and engage management in ongoing dialogue to resolve worksite problems, says Mosquea.

“As a union we need to acknowledge the importance national and international solidarity played in getting us to this stage,” he says. “I especially need to recognize the trainings, organizing support and ongoing accompaniment from the Solidarity Center. It played a fundamental role in our getting to this next stage, when we enter into collective bargaining.”

As a result of this widespread wage theft, many workers say they are forced to eat only one or two meals a day; move repeatedly to access affordable housing; and rent two rooms or fewer for their entire family to make ends meet.

As a result of this widespread wage theft, many workers say they are forced to eat only one or two meals a day; move repeatedly to access affordable housing; and rent two rooms or fewer for their entire family to make ends meet.

The report, which ranks countries based on their efforts to fight forced labor and human trafficking, downgraded Myanmar, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan to the lowest level (Tier 3),

The report, which ranks countries based on their efforts to fight forced labor and human trafficking, downgraded Myanmar, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan to the lowest level (Tier 3),