Sep 10, 2016

Globally, women are paid 30 percent less than men—but “imagine instead of corporations making 30 percent more off women’s labor, imagine if that 30 percent were coming back to our communities in the form of wages,” says Shawna Bader-Blau, Solidarity Center executive director.

Speaking on the panel, “Women’s Economic Empowerment and Workers Rights,” a Solidarity Center-sponsored session at the 2016 Association of Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) Forum, Bader-Blau said challenging such wide-reaching corporate power means “we need to partner across social movements.”

Cross-movement building is a goal and theme of the September 8–11 AWID Forum, where more than 1,800 participants from 120 countries are gathering to find strategies for mobilizing greater solidarity and collective power across diverse movements.

Union and worker association leaders from Brazil, Morocco and the United States taking part in the panel shared how unions are helping empower women to achieve economic justice.

Seventy million women around the world are in labor unions or worker associations, says Bader- Blau. “The labor movement is by definition the broadest movement for women on earth that is membership based.”

“In the frontlines of this battle we have women who are fighting for labor rights”—Saida Bentahar, CDT Morocco.

In Morocco, the Democratic Confederation of Labor (CDT) in Morocco is helping agricultural workers win bargaining rights with their employers. Most of the workers are women, who live in difficult, fragile conditions, says Saida Bentahar, a member of the CDT Secretariat.

“They sometimes cannot read or write, they live in extreme poverty, they are not paid good wages,” she said, speaking through a translator.

Together with the Solidarity Center, the CDT is training women on their workplace rights, including standing up against sexual harassment.

“Some women wouldn’t even speak at first when we would hold sessions but now they really stand up for what they believe,” says Bentahar. “Together they have written a declaration to guarantee stable labor rights. They will now have equal pay, certificates to assure their skills and capacities. They will have equal opportunities for work and training as well.”

Junéia Batista, CUT national secretary in Brazil, describes union women’s efforts to negotiate day care and other key issues in bargaining with employers. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

Junéia Batista, national secretary of the Confederation of Workers Union (CUT) in Brazil, described how women in the confederation have worked to be part of contract negotiations to ensure issues like day care are included, and to achieve leadership since the confederation formed in 1983.

“We want more,” says Batista, speaking through a translator. “It has been 33 years with men, men, men presiding in the presidency,” she says, and women members are working to establish gender equality measures throughout their union structures.

In Mississippi, a state in the southern United States, the Mississippi Worker’s Center for Human Rights (MWCHR) is helping empower working people in Oxford, an impoverished area with a history of racial violence.

“Wages are not the only point of resistance and struggle we need to be dealing with,” says Jaribu Hill, MWCHR executive director.

Panelists also discussed the increasing attacks throughout the world on workers’ ability to form unions.

“Our broader labor movement is suffering from a closing of democratic space,” says Bader-Blau, citing a 30 percent rise in attacks on worker rights around the world. “Our governments, aided by corporate power, are defining worker rights in narrower and narrower terms.”

“In this environment, in this context, we feel it is so important that women’s work be respected and valued … and dignified and that we fight for this,” she says. “The primarily vehicle for fighting for women’s rights at work is trade unionism.”

As Bentahar says, “In the frontlines of this battle we have women who are fighting for labor rights.”

Sep 7, 2016

The 2009 end of Sri Lanka’s civil war was an opportunity for workers to return to the security and protections of the formal economy, which had been destabilized by 26 years of violence. However, a new Solidarity Center survey finds that peace has yet to bring the hoped-for economic gains to workers in Jaffna, the capital of Sri Lanka’s Northern Province. The survey’s findings on working conditions are especially important because the exploitation of workers is not only a setback for healthy industrial relations in Sri Lanka’s economy, but has the potential to aggravate social tensions and interfere with the ongoing process of peacebuilding.

“The bulk of the workers in Jaffna are in low-paid jobs with minimal labor standards, social protection and security of tenure, which are not conducive to creating sustainable livelihoods,” according to the summary.

“A key element to address conflict is equal treatment under the law,” says Tim Ryan, Asia regional program director at the Solidarity Center, who presented the survey’s findings during a recent discussion of the report at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) in Washington, D.C.

According to Ryan, the survey seeks to provide economic data on workers in Northern and Eastern Sri Lanka that go beyond employment statistics. “Are they finding ways to both protect their rights under the law? Are laws and standards being equitably enforced?”

Workers Rights Laws Not Enforced

Despite worker-friendly Sri Lankan legislation like the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF), an employer-funded government social security that has existed for decades, the Solidarity Center’s survey shows a majority of workers—76 percent—do not have the labor rights they are legally guaranteed due to a lack of enforcement. Of that percentage, only 22 percent of female respondents and 46 percent of male respondents say they receive what they are owed by the EPF.

The gendered difference in access to social protections is only one example of a trend persistent throughout the survey’s results, which suggests that female workers are disproportionately disadvantaged under the current conditions. A large wage gap exists between male and female respondents, including between employees doing identical work. The rate of female unemployment is nearly double that of male unemployment. And more than 80 percent of female respondents say they are unaware of their right to overtime benefits, compared with 49 percent of male respondents.

More such initiatives are needed. Although Sri Lanka is a member of the International Labor Organization (ILO), the survey confirms that more progress is needed to move the country toward the goals outlined in the ILO’s agenda for decent work. While ongoing tension and inequalities in Sri Lankan politics complicate the protection of worker rights through legislation, workers’ organizations like trade unions can help hold employers accountable to their employees and bring Sri Lanka in line with the standards of the international community.

“Workers in Post-Civil War Jaffna: A Snapshot of Working Conditions, Opportunities and Inequalities in Northern Sri Lanka” was made possible through a NED grant.

Aug 17, 2016

On a hot, damp morning in Hlae Ku Township, Myanmar, Kyin San surveys the rice fields spread below her, as Mg Zaw, knee deep in mud, drives two oxen to plow the remaining plot. For many years, Kyin San, like most of the farmers in the area, worried that her land would be confiscated for large-scale development, as had so many other farms over the years.

Burmese rice farmer Kyin San says by joining a union, farmers can share strategies and techniques to improve their craft. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

But now, Kyin Sun says, farmers are no longer hesitant to negotiate with the government to settle disputes. Along with 10,000 other farmers in the township, Kyin Sun has joined the Agriculture and Farmer Federation of Myanmar (AFFM), part of the Confederation of Trade Unions–Myanmar (CTUM).

“Through CTUM, we have made much progress,” she says, speaking through a translator.

Farmers across Myanmar are the fastest growing group of workers forming unions since 2011, when a new law allowed creation of unions. Within weeks of the law’s passage, farmers, woodworkers, garment workers, hatters, shoemakers and seafarers quickly registered their unions.

Connecting Farmers

Htay Lwin, president of the Hlae Ku Township agricultural union, says farmers also have sought to join unions to learn new technical skills to improve their farming techniques, a goal Kyin San says has been advanced by union membership.

Union President Htay Lwin says many farmers are joining unions to protect their land from being confiscated for large-scale development. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“Now we can communicate with farmers across the country and share our experience with others,” she says.

AFFM members are connected with the Asian Farmers Association for Rural Development, a regionwide organization based in the Philippines that provides training on seed production, food safety and other issues, says CTUM President U Maung Maung.

Speaking from CTUM offices in downtown Yangon, Maung Maung discussed how the federation is moving forward with the plan he nurtured for decades during his political exile in Thailand.

“We are doing what we wanted to do for the past 30 years—building unions, getting into negotiations with employers, trying to develop policies with labor and management,” he says.

Rebuilding Worker Power after Decades of Dictatorship

Maung Maung was forced into exile after a violent military crackdown targeted thousands of pro-democracy demonstrators and labor leaders, many of whom were sent to prison. He returned to Burma in 2012 and since then, CTUM has helped some 60,000 workers organize unions. CTUM received official government registration last year.

Now, CTUM is working with policymakers to enact social welfare reforms and drafting recommendations for revising the country’s labor laws, many of which were enacted when the country achieved independence from Britain in 1948. After decades of military rule, Myanmar trails many Asian nations economically, and Maung Maung sees much work ahead in modernizing the workforce and developing a culture of social dialogue among workers, business and government common in other countries.

Fundamental to effecting the change CTUM envisions is educating workers about their rights. Workers for many years had no freedom to improve their working conditions, and unions now are helping them understand that they can stand up for their rights—and how to do so.

Because, as Maung Maung says, it all comes down to the workers.

“The workers have to know what they want—and they have to push for it.”

Aug 1, 2016

The World Bank must convey to the Uzbek government that attacks against independent monitors assessing the extent of forced labor in the country’s cotton harvest will not be tolerated. The World Bank must also outline consequences should the attacks continue, according to the Cotton Campaign.

In a July 29 letter to key World Bank officials, the Cotton Campaign, a coalition of dozens of labor and human rights groups that includes the Solidarity Center, wrote:

“The World Bank should take all reasonable measures to create an enabling environment for independent actors to monitor projects that it finances. We have not seen the bank take such measures in Uzbekistan.”

The World Bank Group is providing more than $500 million in financing to the government of Uzbekistan for its agriculture sector and additional financing to multinational companies processing forced-labor cotton in Uzbekistan.

1 Million in Forced Labor During Cotton Harvests

During each fall cotton harvest, the Uzbekistan government forces more than 1 million teachers, nurses and others to pick cotton for weeks, deeply cutting services at schools and medical facilities. Last fall, the government went to extreme measures—including jailing and physically abusing those independently monitoring the process—to cover up its actions.

“The Uzbek government’s repression of human rights monitors has made it impossible for essential mitigation measures of monitoring and grievance redress to function,” according to the coalition, which sent the letter in advance of an early August roundtable meeting of the World Bank, the Uzbek government, the International Labor Organization and diplomatic missions in Uzbekistan.

The coalition also is requesting that the World Bank “obtain an enforceable commitment from the Uzbek government to allow independent journalists, organizations and individuals to have access to all World Bank project-affected areas and to monitor, document and report about forced labor without interference or fear of reprisal.”

Uzbekistan Downgraded in US Trafficking in Persons Report

In June, an Uzbek victim of forced labor in cotton production and three human rights defenders filed a complaint against the World Bank’s private lending arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC). They seek an investigation into forced labor connected to a $40 million loan to Indorama Kokand Textile, which operates in Uzbekistan. The complaint presents evidence that the loan to expand the company’s cotton manufacturing facilities in Uzbekistan allows it to profit from forced labor and sell illicit goods.

Also in June, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, where forced labor in cotton harvests also is rampant, were downgraded to the lowest ranking in the U.S. State Department’s 2016 Trafficking in Persons Report.

Jul 15, 2016

An astounding 80,000 Zimbabwe workers in formal employment—out of some 350,000 workers—did not receive wages and benefits on time in 2014, according to a new Solidarity Center report, “Working Without Pay: Wage Theft in Zimbabwe,” released today in Harare.

As a result of this widespread wage theft, many workers say they are forced to eat only one or two meals a day; move repeatedly to access affordable housing; and rent two rooms or fewer for their entire family to make ends meet.

As a result of this widespread wage theft, many workers say they are forced to eat only one or two meals a day; move repeatedly to access affordable housing; and rent two rooms or fewer for their entire family to make ends meet.

Through first-person interviews and other research by affiliates of the country’s main trade union confederation, the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU), the report provides hard data behind last week’s successful one-day shut-down of businesses, government and services by workers across Zimbabwe outraged over wage theft and a new law targeting market vendors who make up the vast proportion of the workforce.

Paid Only Enough to Get to Work

One woman interviewed in the report, whose experience is not uncommon, says she has received $26 a month in wages for the past eight months, although her monthly salary is $342. Yet basic living costs, which on average include $60 for renting a single room, $30 for electricity, $15 for water and $22 for transportation to work, mean she only has sufficient funds to get to and from her job.

“This failure to pay what workers are legally entitled to is wage theft in that it involves employers taking money that belongs to their employees and keeping it for themselves,” the report states. “This is a clear violation of international labor standards, as well as national legislation on the employment of workers.”

The report traces the ongoing wage theft to 2012, as employers in the public- and private-sector increasingly began delaying wage payments.

Up to 95% of Zimbabweans Work in Informal Economy

Simultaneously, the number of jobs in the informal economy has skyrocketed, the report points out. Some 6.3 million people made up Zimbabwe’s workforce in 2014, of which 5.9 million workers (94.5 percent) were informally employed, compared with 84.2 percent in 2011, according to “Working without Pay.” An additional 800,000 women and men were in the workforce, but unemployed.

Last month, the government introduced a statutory law that bans imports of basic commodities—a law that directly affects hundreds of thousands of informal economy workers who survive on cross-border trading. Up to 95 percent of jobs in Zimbabwe are in the informal economy, and workers say the new law takes away their livelihoods.

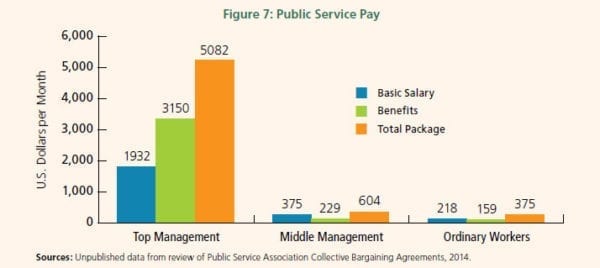

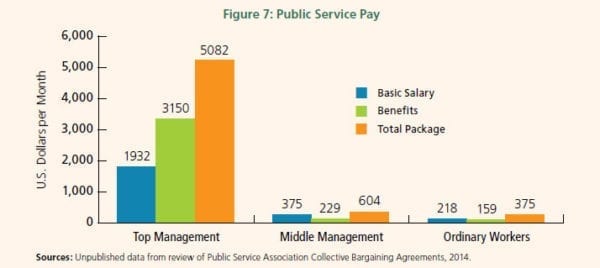

Based on surveys at 442 companies, and the result of extensive research by the Labor and Economic Development Research Institute of Zimbabwe, the report also documents extravagant salaries and benefits to middle and top management even as workers go unpaid and presents recommendations for action to address the problem.

Companies Involved in Wage Theft Must Be Held Accountable

Some of the recommendations include:

- The Ministry of Labor, together with representatives of employers and unions, should review the status of companies that are not paying their workers and assist in developing plans to rectify the injustice.

- Unions representing workers in companies not paying salaries—in full and on time—should demand that the government bring criminal proceedings under the relevant provisions of the Labor Act against employers.

- Trade unions should advocate for payment of interest on late payment.

- The government should set an example by reviewing the wage structure in government agencies and quasi-government agencies to limit benefits to top managers, institute a more just pay scale and prioritize payments to workers through collective bargaining or social dialogue.