Aug 2, 2018

The Constitutional Court of South Africa determined in a historic ruling late last week that workers placed by labor recruiters must be made permanent after three months at the company where they worked on temporary status, entitling them to the same pay, benefits and job security afforded to full-time employees, but labor organizations expect a protracted fight to enforce the ruling.

Zwelinzima Vavi, general secretary of the South African Federation of Trade Unions’ (SAFTU), described the victory as “unprecedented,” congratulating the National Union of Minworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) for its successful—almost four-year battle—through South Africa’s labor courts and the Constitutional Court.

The ruling puts employers on notice, he said. “Sorry, you are going to have to treat all workers the same” finally giving meaning to the ILO Convention which requires equal pay for work of equal value,” said Vavi in a broadcast interview.

However, the Court stopped short of banning labor recruiting, or broking, outright, for which South Africa’s unions and federations have long advocated. Short of a ban, workers say, trade unions and labor federations expect challenges to ensuring enforcement of the ruling.

Sizwe Pamla, a spokesperson of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), said it was unfortunate that the ruling still “justified” labor brokers, whom he said were “trading in workers.”

NUMSA’s general secretary, Irvin Jim warned that workers “still remain vulnerable” under the new ruling because recruiters “will try to do every trick: They will try to replace the worker before three months [end]; they will try to remove him.”

South Africa’s workers have long argued that employers use so-called “temporary” workers to avoid the higher cost of employing permanent workers, an arrangement from which labor brokers profit.

To enforce the ruling, Vavi said, unions and federations must educate workers about their new rights under this ruling.

The Constitutional Court verdict overturns a 2015 judgment that labor recruiters and their clients are dual employers, thus making employers the direct responsible parties for all workers in their workplace after three months. Temporary workers earning $15,500 per year or less are covered by the ruling.

Labor recruitment in South Africa generated more than 2.5 billion U.S. dollars in 2013, employing over 1 million so-called temporary workers, or 7.5 percent of total employment.

Jul 31, 2018

Around the world, workers, their unions and other associations are striving to promote the rights of working people at their jobs and in their everyday lives.

While every job has value, not all jobs are “good jobs.” Millions of jobs around the world do not offer the social protections or the sense of dignity that allow workers to enjoy the benefits of their own hard work.

The Solidarity Center works with unions and other allies to empower workers around the world to achieve decent work together.

WHAT MAKES A “GOOD JOB”?

In Thailand, Burmese migrant workers and their families learn about their rights on the job through training programs organized by the Human Rights Development Foundation (HRDF), a Solidarity Center ally.

But what are those rights? What makes a job a “good job”?

At the Pae Pla Pier in Mahachai, Thailand, Burmese dockworkers cart barrels of fish. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy

GOOD JOBS ARE SAFE

At the Gldani Metro Depot in Tbilisi, Georgia, employees work with dangerous chemicals and face constant danger from high voltage electrical wires. Their union, the Metro Workers’ Trade Union of Georgia (MWTUG), is addressing these safety and health risks with assistance from the Solidarity Center.

At the Gldani Metro Depot in Tbilisi, Georgia, employees like repairman Tamaz Simonishvili work with dangerous chemicals and face constant danger from high voltage electrical wires—safety and health risks his union, Metro Workers’ Trade Union of Georgia, is addressing with the assistance of the Solidarity Center. Credit: Solidarity Center/Lela Mepharishvili

The Solidarity Center also partners with numerous unions and worker associations in Bangladesh to train garment workers in fire safety and other measures to improve their working conditions.

The Solidarity Center partners with numerous unions and worker associations in Bangladesh to train garment workers in fire safety and other measures to improve their working conditions. Credit: Solidarity Center

GOOD JOBS PAY LIVING WAGES

At the Palmas del César palm oil extraction plant in Minas, Colombia, workers are represented by Solidarity Center union ally Sintrapalmas-Monterrey. The union organized subcontracted workers into its bargaining unit, significantly improving their wages, benefits and job conditions.

At the Palmas del César palm oil extraction plant in Minas, Colombia, workers are represented by Solidarity Center union ally Sintrapalmas-Monterrey. The union organized subcontracted workers into its bargaining unit, significantly improving their wages, benefits and job conditions. Credit: Solidarity Center/Carlos Villalon

In Sri Lanka, where jobs are shifting from the industrial to service sector, workers like members of Food, Beverage and Tobacco Industry Employees’ Union (FBTIEU) are forming unions in the hotel and tourism sectors to ensure that the new jobs pay living wages and offer social benefits.

In Sri Lanka, where jobs are shifting from the industrial to service sector, workers like members of Food Beverage and Tobacco Industry Employees’ Union are forming unions in the hotel and tourism sectors to ensure the new jobs pay living wages and offer social benefits. Credit: Solidarity Center/Pushpa Kumara

GOOD JOBS TAKE CARE OF WORKERS

The National Union of Mine, Metal, Steel and Allied Workers of the Mexican Republic (SNTMMSSRM, known as “Los Mineros”) has won many bargaining pacts that include significant economic benefits and essential safety and health protections for workers.

A miner in Mexico’s Baja California Sur, Ruth Rivera also is a shop steward for her union, SNTMMSSRM (Los Mineros), which has won bargaining pacts that include significant economic benefits and essential safety and health protections. Credit: Solidarity Center/Roberto Armocida

Agricultural workers in Rustenburg, South Africa, are members of the Food and Allied Workers Union (FAWU), a Solidarity Center partner, which represents migrant farm workers in Mpumalanga Province and assists them in gaining access to health care and other services.

A FAWU member plants cabbage seedlings on a farm in Rustenburg, South Africa. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jemal Countess

GOOD JOBS GIVE WORKERS A BREAK

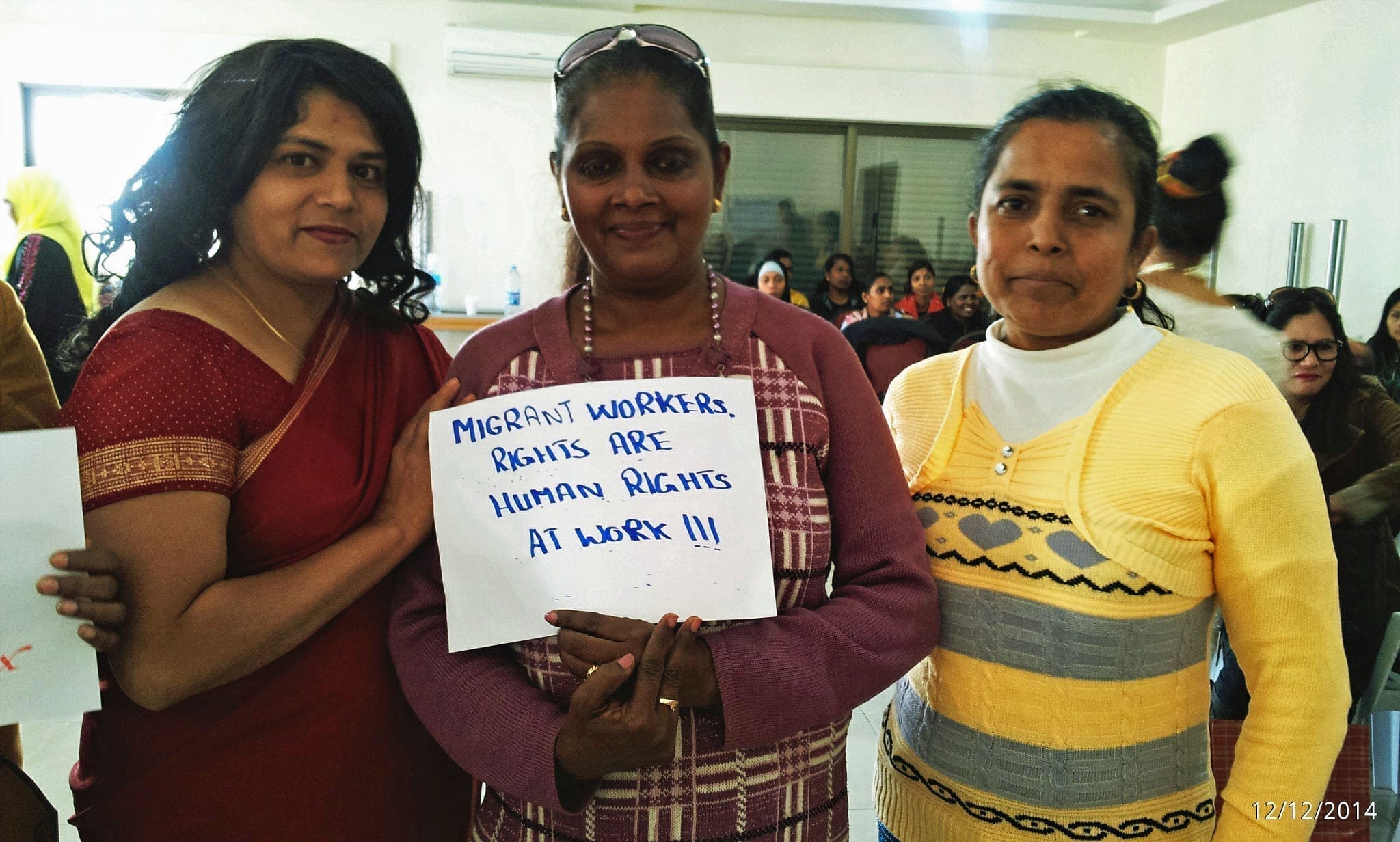

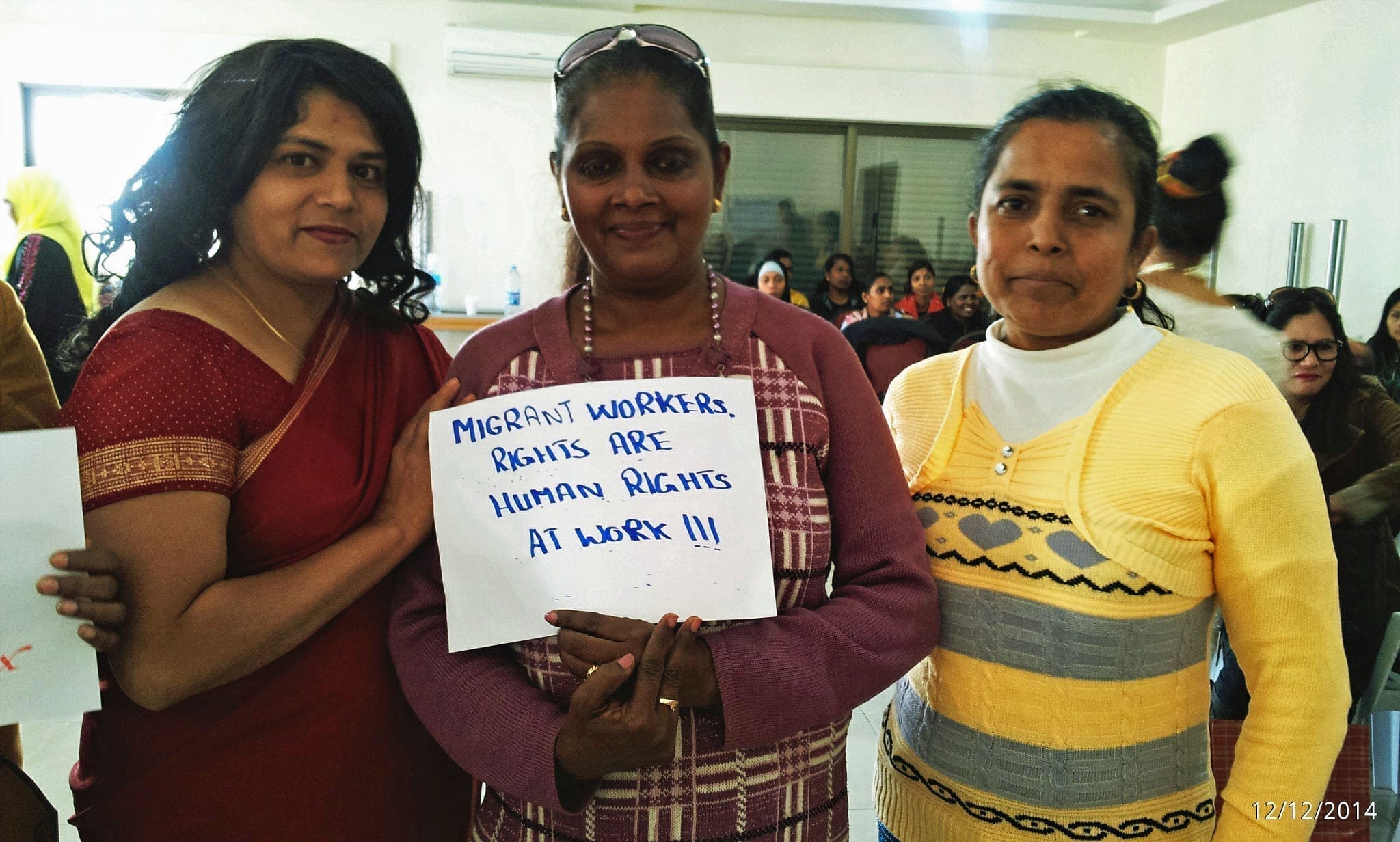

Across the Arab Gulf, more than 2.4 million migrant domestic workers often toil 12–20 hour days, six or seven days a week. Domestic workers in Jordan recently formed a worker rights network that advocates for better working conditions and includes migrant workers from Bangladesh, Indonesia, the Philippines and Sri Lanka.

Sri Lankan domestic workers in Jordan defend their rights. Credit: Solidarity Center/Francesca Ricciardone

The Kenya Union of Domestic, Hotel, Educational Institutions, Hospitals and Allied Workers (KUDHEIHA), a Solidarity Center partner, has been at the forefront of championing the rights of domestic workers at the national level and working locally to organize workers into the union and educate them about their rights.

The Kenya Union of Domestic, Hotel, Educational Institutions, Hospitals and Allied Workers union, a Solidarity Center partner, has been at the forefront of championing the rights of domestic workers at the national level and working locally to organize workers into the union and educate them about their rights. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Holt

GOOD JOBS EMPOWER WOMEN

Dozens of journalists and media professionals have taken part in the Solidarity Center’s ongoing Gender Equity and Physical Safety training in Pakistan, identifying priority gender equality issues at their workplaces and in their unions, and outlining strategies for addressing those issues.

Journalists in Pakistan participate in Solidarity Center-sponsored gender equality workshops. Credit: Solidarity Center/Immad Ashraf

Through her union, the Palestinian General Federation of Trade Unions Workers Union (PGFTU) and the Solidarity Center, kindergarten teacher Khadeja Othman says she has gained new skills in workshops, training courses and hands-on experience.

Khadeja Othman, a Palestinian kindergarten teacher in Ramallah’s Bet Our Al Tahta village. Credit: Solidarity Center/Alaa T. Badarneh

ORGANIZED WORKERS HELP CREATE GOOD JOBS

Workers and their families on the Firestone rubber plantation used their union, the Firestone Agricultural Workers Union of Liberia (FAWUL), to negotiate work quotas that could be met without the need for children to assist their parents. Children also now receive free education as a result of union negotiations.

Opa Johnson, a rubber tapper on the Firestone plantation, is a member of the Firestone Agricultural Workers Union of Liberia, which negotiated work quotas that could be met without the need for children to assist their parents. Children also now receive free education as a result of union negotiations. Credit: Solidarity Center/B.E. Diggs

Even self-employed workers have organized to defend their right to decent work. The Zimbabwe Chamber of Informal Economy Associations (ZCIEA), a Solidarity Center partner, trains negotiators in collective bargaining with municipalities to provide adequate space for vendors and other informal workers throughout their cities.

Nyaradzo Tavariwisa makes and sells peanut butter to support her family. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jemal Countess

UNIONS HELP MAKE JOBS BETTER

Working people time and again have proven that when they are free to form and join unions and bargain for better working conditions, they can achieve decent work, improve their lives and benefit their families and communities.

In Peru, two unions, both Solidarity Center allies, represent palm workers on plantations and in processing factories. These unions have helped improve dangerous working conditions, access to healthcare and job stability through collective bargaining and labor inspections.

Peruvian palm oil workers travel across the plantation where they live and work. Credit: Solidarity Center/Oscar Durand

THE SOLIDARITY CENTER HELPS WORKING PEOPLE ATTAIN DECENT WORK

Decent work means employment that provides living wages in workplaces that are safe and healthy. Decent work is about fairness on the job and social protections for workers when they are sick, when they get injured or when they retire.

Jul 31, 2018

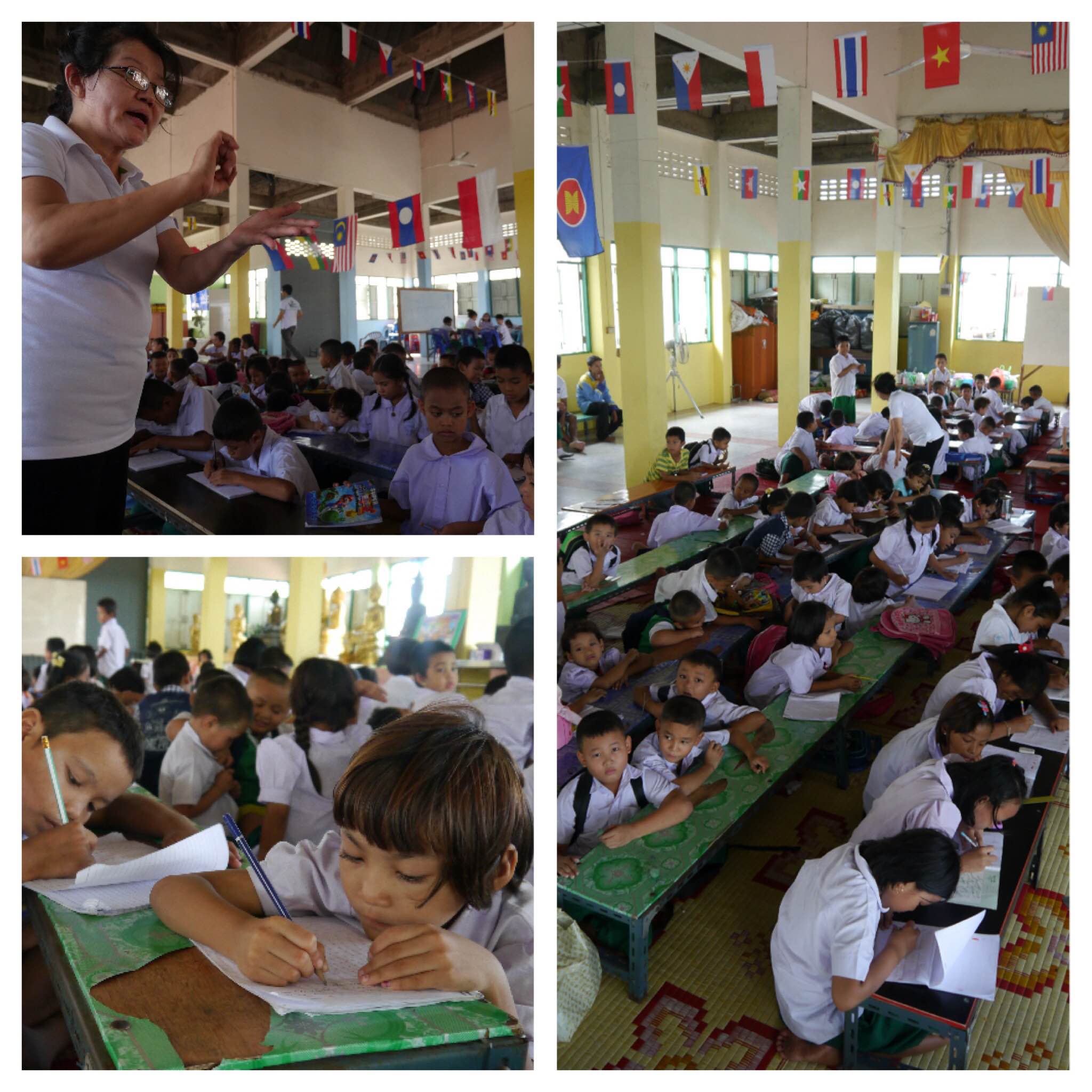

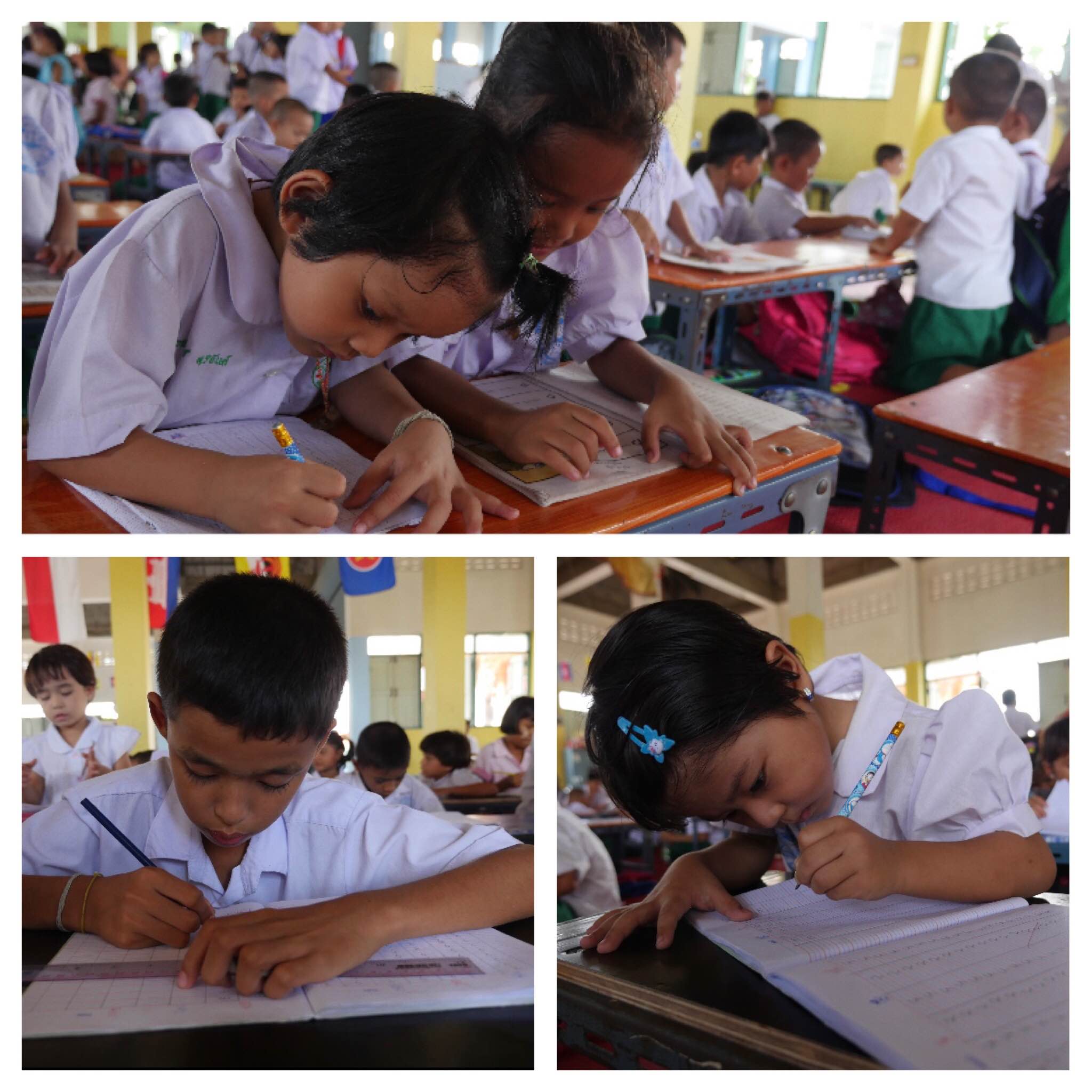

The migrant children diploma center opened in 2013 as the first school for children of Burmese migrant workers in the community known as “little Burma” located an hour outside Bangkok in Mahachai, Thailand.

Thousands of children accompany their parents who are among the estimated 200,000 Burmese migrant workers in Mahachai.

The school is supported through donations from private companies, religious organizations, and migrant workers who contribute 60 Thai baht (USD 1.68) a month to pay the salaries of the seven teachers.

More than 200 students attend this elementary school based in a Buddhist temple. For many of them, it is their first experience with formal education.

NOW IS NOT THE TIME FOR KIDS TO WORK

When parents are protected at work, kids can go to school.

Jul 27, 2018

Aldaberdi Karimov, 42, who lives in a remote Kyrgyzstan village in the Batken region, did not want to migrate from his country to find work to support his family, including his daughter, Ak Maral, now 5 years old.

But like many in Kyrgyzstan, where remittances from workers abroad make up more than 25 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, Karimov faced the heart-wrenching decision to leave his family to find employment. In fact, so few good jobs are available in the country, especially for workers in rural areas, only 24 percent of Kyrgyz workers are employed in the formal economy.

Aldaberdi Karimov escaped from forced labor and is back in his Kyrgyz village with his family, including his daughter, Ak Maral. Credit: Solidarity Center

And when he left his village, Karimov had no idea he would be a target of force labor and human trafficking. Globally, more than 21 million people are in forced labor, according to the International Labor Organization, which on July 30 marks World Day against Trafficking in Persons.

Forced to Live with Cows in the Barn

Karimov first sought jobs in Russia and then migrated to Kazakhstan, where he worked as a market vendor in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city. Karimov thought he would fare better in Kazakhstan because, like Kyrgyzstan, it is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union.

Between 100,000 to 150,000 Kyrgyz were registered in Kazakhstan at the end of 2017, figures that do not reflect many who are not registered, according to a new report by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). Most work without written contracts or on contracts that do not adequately protect their rights. Their passports typically are confiscated by employers, making it difficult for them to leave abusive jobs, and they have no access to labor protections like safe working conditions and paid leave.

Karimov could not afford the permit needed to sell goods legally in Kazakhstan—costing between $1,500 and $2,000, a permit is the equivalent of a year’s wage. Through an intermediary, he and his brother, Giyazidin, were led to a job on a Kazakh farm in June 2016 tending 100 cows and 2,000 sheep. The farmer said he would pay them 40,000 tenge ($117) each per month.

“The employer promised to pay us not every month, but once every three or four months,” Karimov says. “After three months, we asked for an advance and our employer became very angry and said that the cows and sheep are very thin, so he is not going to pay yet.”

By October, they each had been paid only $100 for six months’ work. Frost and cold rains began and when the brothers asked to be housed in a warmer environment than their small thatched hut in the field, the employer told them to live with the cows and rams in the barn.

Tens of Thousands of Workers in Forced Labor in Kazakhstan

Essentially trapped in forced labor, the brothers made their escape after Giyazidin became so ill that the farmer took him to the hospital. Tens of thousands of workers are estimated to be victims of forced labor in Kazakhstan, with migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan forced to labor in agriculture, construction and the extraction industry.

Like many migrant workers, neither Karimov nor his brother reported their abuse to the police because they did not trust them. In fact, officers of law enforcement agencies often are the link between migrant workers and “buyers” of labor, according to the FIDH report.

Karimov says lack of a labor contract and no police protection left him and his brother vulnerable to human traffickers and inhumane working conditions. Around the world, most migrant workers are denied the right to form unions and bargain with their employer—a fundamental freedom that enables abuse and exploitation. “The lack of labor agreements entails forced labor and even slavery,” says Aina Shormanbayeva, president of the Legal Initiative, a Kazakhstan-based public foundation.

Now back in his village, Karimov says migrating for jobs is now out of the question, even as he searches for work, still seeking wages that will enable him to support his family

Jul 19, 2018

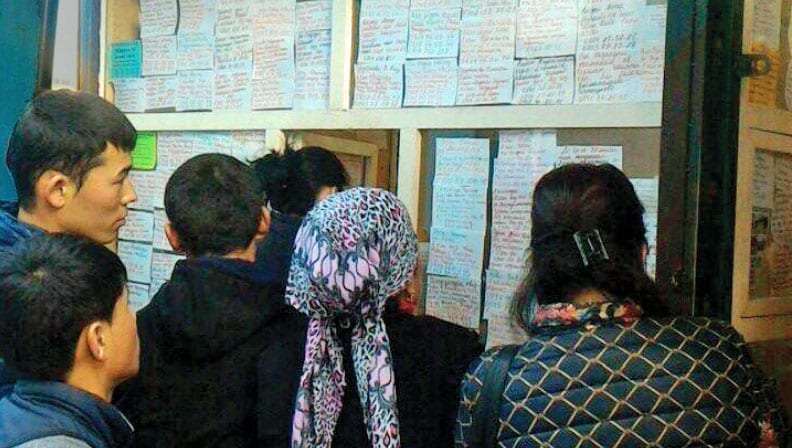

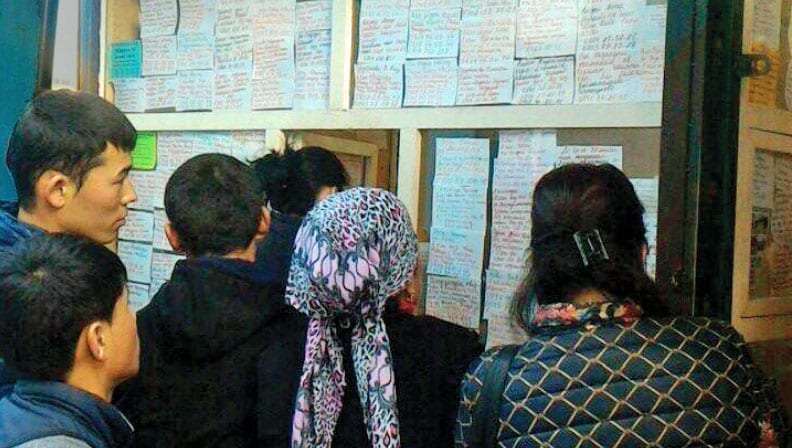

Workers who migrate from Kyrgyzstan to Kazakhstan for jobs often do not receive their wages, are forced to work in unsafe and abusive conditions and even are kidnapped and held against their will in forced labor, according to a new report.

“Invisible and Exploited in Kazakhstan” also found that children are forced to labor, with young girls between ages 12 and 17 working as nannies, and boys working in markets and on farms. The report is based on the findings of a series of missions by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and its partners from September to November 2017 in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. The Solidarity Center contributed extensively to the report.

“The right to freedom of association is a core principle of human rights and worker rights, including when workers are migrating for jobs,” says Lola Abdukadyrova, Solidarity Center program coordinator. Abdukadyrova spoke yesterday at a press conference in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, where the report was released.

Bedroom of five migrant workers in the basement of a construction site in Kazakhstan, November 2017. Credit: FIDH

Between 100,000 to 150,000 Kyrgyz were registered in Kazakhstan at the end of 2017, figures that do not reflect many who are not registered. Most work without written contracts or on contracts that do not adequately protect their rights. Their passports typically are confiscated, making it difficult for them to leave abusive employers, and they have no access to labor protections like safe working conditions and paid leave.

“The lack of labor agreements entails forced labor and even slavery,” says Aina Shormanbayeva, speaking at the press conference, which drew nearly two dozen reporters. Shormanbayeva is president of the Legal Initiative, a Kazakhstan-based public foundation.

Some 81,600 workers were victims of forced labor in Kazakhstan in 2016, according to estimates by the nonprofit Walk Free Foundation, with migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan forced to labor in agriculture, construction and the extraction industry.

Women Migrant Workers Targets of Gender-Based Violence

While some one-third of all migrants were women two to three years ago, the report finds women now comprise half of migrant workers. Women are especially vulnerable, facing gender-based violence in agricultural fields and in employers’ homes when working as domestic workers. They may lack medical care while pregnant and often are fired when employers learn of their pregnancy.

Says one woman migrant worker: “I work as a janitor from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., and when there are banquets, until 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. Lunch breaks are 30 minutes maximum. There are no days off. I work every day. Some people can’t prove anything when they don’t get paid because nothing is documented. One woman worked at a car wash, they told her they didn’t have money and so they didn’t pay her. This happens to many people.”

Solidarity Center’s Lola Abdukadyrova, (second from left), discussed the plight of migrant workers in Kazakhstan during a press conference in Bishkek. Credit: Solidarity Center

The report finds migrant workers are not aware of their rights on the job, and they rarely appeal for protection of their rights when their employers perform illegal actions. They also do not believe police are able to protect their rights. In many cases, officers of law enforcement agencies are the link between migrant workers and buyers.

“Kazakhstan has not taken effective measures to prevent, investigate and prosecute persons involved in providing illegal intermediary services, and has not ensured effective legal protection for the victims,” the report states. Kazakh authorities argue that it is not their responsibility to protect migrant workers, and that protection of migrant workers is the responsibility of Akims (heads of regional or local authorities).

Kazakhstan was recently rated one of the 10 worst countries for workers by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). Union leader Larisa Kharkova was sentenced in 2017 to four years of restrictions on her freedom of movement, a ban on holding public office for five years and 100 hours of forced labor on false charges of embezzlement. Kharkova led the Confederation of Independent Trade Unions of Kazakhstan, which was ordered closed by a court ruling. Independent trade unions in Kazakhstan face ongoing attacks on freedom of association and basic trade union rights.

Over the past five years, the Solidarity Center in Kyrgyzstan has worked extensively to advance migrant worker rights, including holding awareness-raising campaigns for potential migrants and their families; supporting a hotline on labor migration issues; and assisting unions in protecting and promoting migrants’ worker rights.