Aug 7, 2019

At least five union activists were murdered in Guatemala in 2018, and union leaders and members in Guatemala and Honduras suffered dozens of incidents over the past year for standing up for worker rights, including restriction of union rights, intimidation, harassment, illegal detention, death threats and attempted murder, according to two new reports.

In Guatemala, union leaders and members reported 882 crimes to the Office of Crimes Against Trade Unionists, including coercion, kidnapping and murder. Yet there were only two convictions, according to the Annual Report on Anti-Union Violence in Guatemala. Incidents against union activists in Honduras were concentrated in the department of Cortés in northern Honduras, which includes the major industrial city of San Pedro Sula, as well as a key agricultural area where banana and palm plantation workers are struggling to win decent wages and working conditions.

Both reports recommend that unions prioritize registering incidents of violence against union activists, incorporate gender analyses to prevent and demand protection from gender-based violence and harassment at work, and urge the governments to work across agencies and departments to prevent union violence, protect victims and end impunity.

Honduran Agricultural Workers Targeted in 2018

Union leaders in the area from the agro-industrial union STAS, the banana union SITRATERCO and other unions represented 26 of the 38 total victims of anti-union violence between February 2018 and February 2019, according to the report, Resisting Anti-Union Violence in Honduras. Women who were targeted often received threats against their mothers and children, the report finds.

Union leaders in the area from the agro-industrial union STAS, the banana union SITRATERCO and other unions represented 26 of the 38 total victims of anti-union violence between February 2018 and February 2019, according to the report, Resisting Anti-Union Violence in Honduras. Women who were targeted often received threats against their mothers and children, the report finds.

The number of incidents of anti-union violence has steadily increased since the network’s first report, from 14 in 2015 to 39 in 2017, with one less incident in 2018. Union anti-violence networks in Honduras and Guatemala, supported by the Solidarity Center, annually issue reports documenting violence and intimidation against worker rights activists.

Agricultural worker activists represented 86 percent of the victims of anti-union violence in Honduras, a startling shift from past years, when state and public-sector violence against union leaders and activists represented a majority of incidents, according to data in previous reports. The remaining incidents in 2018 were directed at public employees.

“Stopping the systematic aggressions like those faced by STAS, SITRASEMCA, SITRATERCO and SITRAINFOP is an urgent responsibility for the state of Honduras,” according to the report.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) held back-to-back hearings at the International Labor Conferences (ILC) in 2018 and 2019 on Honduras’s failure to abide by its international commitments. The ILC report in 2018, which expressed “deep concern at the large number of anti-union crimes, including many murders and death threats, committed since 2010,” urged the Honduran government to protect vulnerable unionists, investigate more than a decade of unsolved murders of union leaders and prosecute those responsible for the crimes.

Among union activists murdered in Guatemala, Domingo Nach Hernández, a member of the Workers’ Union of the Municipality of Villa Canales, was found dead in June 2018, days after being kidnapped. Soon before he disappeared, the union had won back the jobs of several workers who were illegally fired. Hernández had previously received death threats and reported them to authorities, according to the Guatemala report.

Freedom to Form Unions Under Attack

In 2014, Guatemala overtook Colombia as the deadliest country in the world for trade unionists. Since then, the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) has consistently named Guatemala one of the 10 worst countries in the world to be a worker, in its annual Global Rights Index, with a rating of 5—“No guarantee of rights”—on its 5-point scale. Honduras is similarly ranked. Countries with a 5 rating are the worst countries in the world in which to be a worker. While they may have legislation that spells out certain worker rights, workers effectively have no access to these rights and are exposed to autocratic regimes and unfair labor practices, according to the ITUC.

Violence is widespread in both countries, but attacks on worker rights activists specifically seek to weaken or eradicate the unions and their work to build citizenship, both reports note. Few perpetrators are brought to justice in either country, with only two convictions in 2018 for crimes against unionists in Guatemala, for example.

When workers seek to join unions and bargain collectively, violence is among the many obstacles they face, as employers harass and intimidate workers generally without repercussion, despite both countries’ stated support for worker rights.

“Freedom of association in Guatemala continues to be very limited, despite current legislation on human and trade union rights and the ratification of international agreements,” the Guatemala report states, noting that many worker rights activists who receive threats fear reporting it to the network for fear of reprisals.

Few Jobs, Low Wages Result in Endemic Poverty

With few jobs available in Guatemala and Honduras, workers in both countries are struggling to survive in the face of endemic poverty. According to the Honduran union anti-violence network, more than 2 million Hondurans live in conditions of “relative poverty,” while nearly 4 million live in “extreme poverty”—in a country with 9 million people. Some 80 percent of those who work are paid less than the minimum wage, the report says.

More than 70 percent of Guatemalans with jobs labor in the informal economy, with low wages, lack of job security and often dangerous working conditions. Nearly half of children younger than 5 suffer from chronic malnutrition, and almost 20 percent of the population cannot read nor write, according to the Guatemalan union anti-violence network, limiting opportunities for better-paying jobs.

The United States brought trade complaints against the governments of Guatemala and Honduras for failing to enforce their own labor laws under the CAFTA-DR trade agreement. The Guatemala case lasted eight years and, despite overwhelming evidence of systemic labor rights violations, an arbitration panel cited a lack of evidence that worker rights violations impacted trade. The Honduras complaint is still active, and the U.S. government is working with the Honduran government, employers and the labor movement on a worker rights monitoring and action plan.

Aug 6, 2019

Workers in Morocco are protesting unilateral moves by the government to restrict strikes and limit other worker freedoms and are collecting signatures against a draft bill, now in parliament.

“The path the government wishes to follow by introducing this legislation on strikes is in total contradiction with the Constitution of Morocco, which guarantees public freedoms, as well as the right of trade unions and other civic associations to defend the rights of their constituents,” says Touriya Lahrech, a worker rights activist and member of National Council of the Democratic Labor Confederation (CDT). Lahrech also is an elected official in the House of Councillors, Morocco’s upper Parliament.

Stating that the right to strike is a “fundamental human right without any restrictions,” one guaranteed in Morocco’s constitution, the Moroccan Labor Union (UMT) says the government’s proposed law “binds it, criminalizes it and makes it impossible to practice.”

The unions are calling on the government to return to discussions with unions and employers, a longstanding practice that union leaders say the government has abandoned and which workers nationwide have protested for months. In February, workers held a general strike, followed by several days of marches to protest unilateral government actions affecting workers.

The unions also are urging the government to withdraw the draft strike law, which they say is counter to International Labor Organization (ILO) regulations covering freedom to form unions (Convention 87) and the right to bargain collectively (Convention 98).

The CDT says the government’s move to unilaterally revise the labor code stems from corporations seeking “flexibility” among civil servants and educators, a term employers often use as a euphemism to describe workplace policies that benefit management at the expense of working people.

Morocco unions are receiving international support for their struggle, including from the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), the AFL-CIO, the Arab Trade Union Confederation (ATUC) and the global union IndustriALL.

“IndustriALL global union urges the government of Morocco to withdraw the draft law on the right to strike, which was written and submitted unilaterally to Parliament for adoption, and has not been the subject of tripartite discussions with partners,” says IndustriALL General Secretary Valter Sanches.

Says Lahrech: “We demand that the government freeze all discussions on this draft legislation and engage in dialogue regarding collective bargaining, and social dialogue that guarantee the rights of the working class to defend its interests.”

Jul 31, 2019

After more than 10 years of partnership with agricultural workers on the Firestone Liberia rubber plantation in Harbel, the company is increasingly backtracking, including the unilateral firing of 13 percent of its workforce, says the Agriculture Agro-Processing and Industrial Workers Union of Liberia (AAIWUL). As the country’s largest employer—and therefore its employment-standards trendsetter—the union says the company’s reversal is having devastating consequences on the livelihood, rights and dignity of Liberia’s workers.

“Although we want jobs, we want good jobs,” said AAIWUL General Secretary Edwin Cisco. “Firestone Liberia is key.”

Workers’ gains on the Firestone Liberia plantation have increased in successive negotiated agreements with the company since 2008, including an end to child labor, improved pay, lower daily production quotas for rubber tappers, mechanized transportation of latex, improved housing, free education for workers’ children and access to medical clinics for workers and their families. The company’s partnership with its workers and subsequent improvements in conditions and pay have set country-wide standards for acceptable conditions of work.

“Generation after generation of workers suffered. We cannot go back,” said Cisco.

Unfortunately, since former president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s leadership ended in 2018, Firestone Liberia is increasingly reversing direction. The company, AAIWUL says, is reneging on its promises and undermining the union with unlawful dismissals of its leaders and large-scale layoffs of full-time union members, who are being hired back as contract workers.

“They are paid off with pain in their hearts,” said AAIWUL President Abraham Nimene.

Firestone Liberia is setting a bad example for other employers investing in the country, including multinational palm oil companies such as Golden Veroleum, which AAIWUL is organizing. Workers harvesting palm oil sought the union’s help to remedy appalling conditions—including workers’ use of dangerous chemicals without personal protection or other safety measures.

In the union’s most serious challenge, Firestone Liberia is increasingly funneling full-time union members into informal contract positions. 320 workers laid off earlier this year were rehired as contractors, joining 2,505 other contractors already working without the benefits accruing to full-time workers. Contract employees are doing the same work as full-time workers, says AAIWUL, for less pay, under worse conditions and without the wages, benefits and social protections enjoyed by full-time workers who are represented by the union. The company says that more layoffs are coming next month.

“They are going to turn the entire workforce into precarious work, and we can’t allow this to happen,” said Nimene.

By AAIWUL’s calculations, 830 jobs have been lost so far this year, after Firestone imposed transfers to contract positions, lay-offs and forced retirements. Although the company says job losses are caused by concessions it made to the country under the Sirleaf government as well as low natural rubber production and decreasing global natural rubber prices, AAIWUL criticizes the company’s lack of transparency in its financial hardship claim. Wages remain low, says AAIWUL. Although president and managing director of Firestone-Liberia, Edmundo Garcia, told the Liberia House of Representatives in 2018 that the lowest wage paid to locally hired workers is $8.36 per day, AAIWUL says that the company’s minimum daily wage for local hires is only $5.60 per day. Production on the plantation continues, said Cisco, but with increasingly exploited, precarious workers.

“We want … the basic labor rights of workers maintained,” he said.

Firestone Liberia, an indirect subsidiary of Bridgestone Americas Inc., is the largest contiguous natural-rubber producing operation in the world. The company supplies Bridgestone with raw and block latex with which to manufacture tires in the United States.

A series of agreements between workers and Firestone Liberia between 2008 through 2019 addressed conditions described in a 2006 human rights lawsuit against the company as “the modern equivalent of slavery.” After a more than one-year struggle, Firestone Liberia plantation workers signed their first agreement with the company in 2008, marking the first time the company’s workers were represented by an independent union in Firestone Liberia’s 82-year history.

Jul 18, 2019

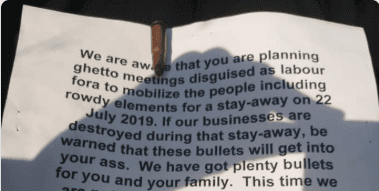

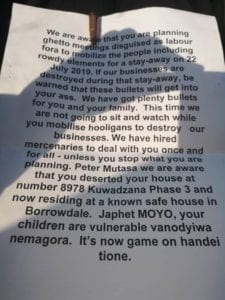

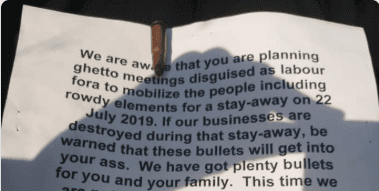

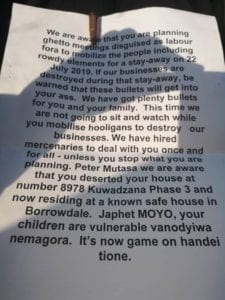

Bullets and an anonymous death threat were delivered to Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) President Peter Mutasa and Secretary General Japhet Moyo yesterday in an apparent attempt to discourage a planned labor action later this month.

“This is the first time, for all we know in our history, that bullets are delivered at the homes of trade union leaders, said ZCTU in response.

Union leaders in Zimbabwe say this is the first time leaders have been threatened with death for seeking to exercise freedom of association. Credit: ZCTU

The identical threatening letters warn Mutasa and Moyo not to participate in an upcoming July 22 work stoppage by ZCTU members who, with other civil society groups, have been protesting rising prices in the country—including a 150 percent fuel price hike.

If Mutasa and Moyo “mobilize the people” the letter warns, the letter’s authors have hired mercenaries “to take care of you once and for all,” “have got plenty of bullets for you and your families” and know where Mutasa–currently in hiding for his own safety—is living.

“It’s now game on,” the letter ends.

ZCTU has faced numerous threats from authorities while Zimbabwe’s economy continues to flounder and inflation and price hikes further complicate Zimbabwean workers’ lives.

Mutasa has been forced into hiding by ongoing violence and intimidation by authorities. After ZCTU helped organize a national strike in January this year to protest price hikes, police seeking Mutasa allegedly assaulted his brother at his home. ZCTU staff also reported intimidation by police. Arrested and charged with subversion, Mutasa and Moyo have since remained in legal limbo as the Zimbabwe government repeatedly postpones their trials.

January’s violent clashes resulted in 12 deaths and 320 injuries, blamed by human rights organizations on the army and police.

In the aftermath of a similar protest in October last year, some trade unionists were beaten, Mutasa, Moyo and 33 other trade unionists were arrested, senior ZCTU leadership was forced into hiding and ZCTU Harare offices were cordoned off by some 150 policemen. The Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission found that torture of protesters by government forces before and immediately after the October national protest—consisting mostly of “indiscriminate and severe beatings”—was widespread.

An attempted fact-finding visit by a delegation of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) in February this year resulted in denial of visas for most of the delegation and the arrest of ITUC-Africa Secretary General Kwasi Adu Amankwah by state security.

The majority of Zimbabwean workers eke out a living in the informal economy, struggling to survive on less than $1 a day. Those with formal jobs often do not fare well either. A 2016 study by the Solidarity Center found that 80,000 workers in formal jobs did not receive wages or benefits on time, if at all. In many cases, they made only enough to get to work.

Jul 8, 2019

Some 650 million workers around the world earn less than 1 percent of global income—a figure that has barely changed in 13 years, according to a new International Labor Organization (ILO) report. At the national level, the share of income going to workers is actually falling, decreasing from 53.7 percent in 2004 to 51.4 percent in 2017.

“The average pay of the bottom half of the world’s workers is just $198 per month and the poorest 10 percent would need to work more than three centuries to earn the same as the richest 10 percent do in one year,” says Roger Gomis, an economist in the ILO Department of Statistics.

The report pushes back on the widely held view that overall income inequality is declining in the global south. Rather, increasing prosperity in China and India is skewing the data, which indicate pervasive income inequality in jobs around the world.

The report pushes back on the widely held view that overall income inequality is declining in the global south. Rather, increasing prosperity in China and India is skewing the data, which indicate pervasive income inequality in jobs around the world.

Overall, 10 percent of workers receive 48.9 percent of total global pay, while the lowest-paid 50 percent of workers receive just 6.4 percent, a new ILO dataset reveals, the ILO Labor Income Share and Distribution finds.

And the more top earners make, the less everyone else is paid, according to the report. But when income of middle- and lower-paid workers rises, everyone but the top earners gain.

The pay gap is especially large in struggling economies. In sub-Saharan Africa, the bottom 50 percent of workers earn only 3.3 percent of labor income, compared with the European Union, where the same group receives 22.9 percent of the total income.

“The majority of the global workforce endures strikingly low pay and for many having a job does not mean having enough to live on,” Gomis says.

Get Involved with Sustainable Development Campaign

The ILO data, requested by the ILO Global Commission on the Future of Work, will be used to monitor progress toward the United National Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs.) Representatives from around the world are set to meet this month for the High-Level Political Forum on some of the sustainable development goals, including SDG 8, which focuses on promoting sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full employment and decent work for all.

(The International Trade Union Confederation has launched a #Timefor8 campaign. Find out how you can take part.)

The ILO Labor Income Share and Distribution dataset includes 189 countries and provides the first internationally comparable figures of the share of GDP that goes to workers—rather than capital—through wages and earnings. It also looks at how labor income is distributed.

Union leaders in the area from the agro-industrial union STAS, the banana union SITRATERCO and other unions represented 26 of the 38 total victims of anti-union violence between February 2018 and February 2019, according to the report, Resisting Anti-Union Violence in Honduras. Women who were targeted often received threats against their mothers and children, the report finds.

Union leaders in the area from the agro-industrial union STAS, the banana union SITRATERCO and other unions represented 26 of the 38 total victims of anti-union violence between February 2018 and February 2019, according to the report, Resisting Anti-Union Violence in Honduras. Women who were targeted often received threats against their mothers and children, the report finds.