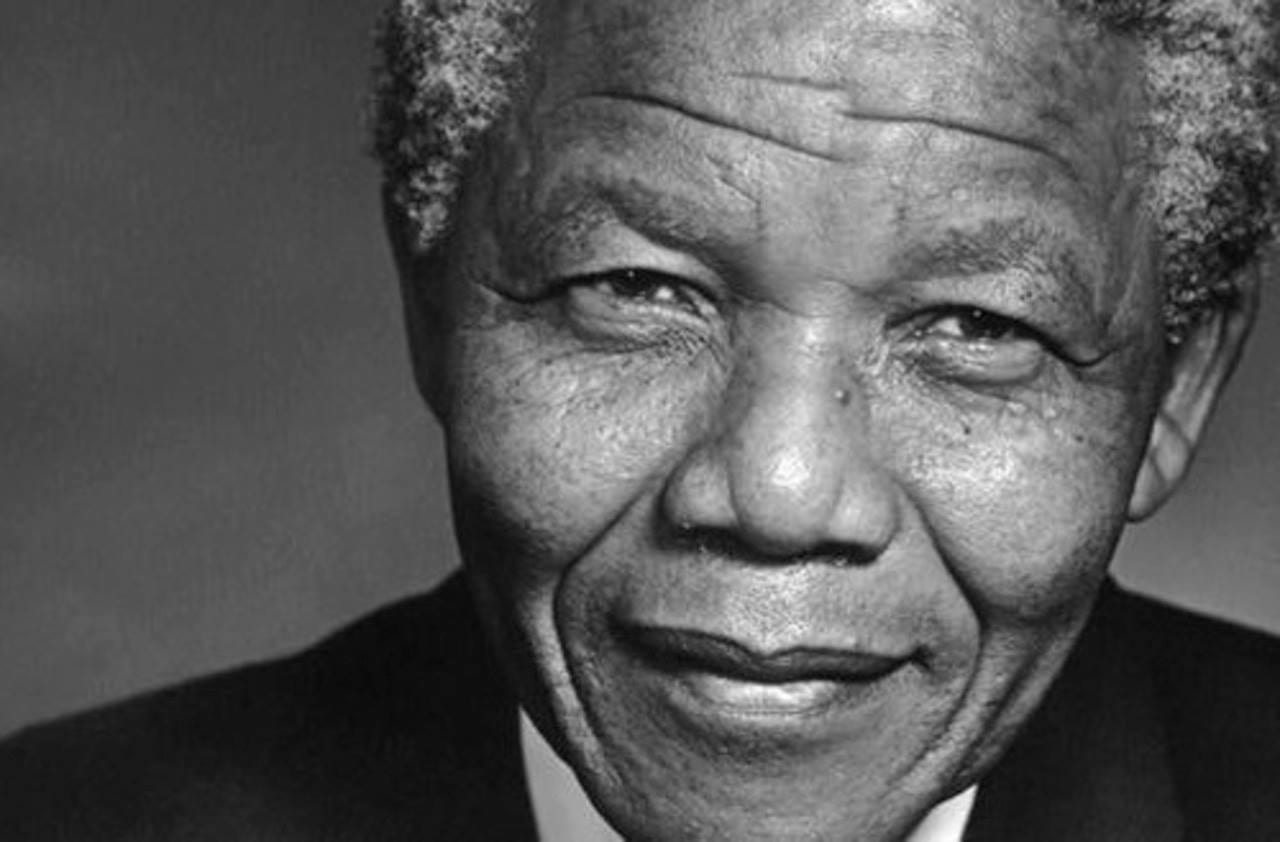

Stanislaw Cieniuch, former Ambassador of the Republic of Poland to South Africa (1991-1997), recalls his firsthand experiences with anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela under South Africa’s apartheid regime. Cieniuch is Solidarity Center Kyrgystan Country Director.

I have been the fortunate witness and participant in two of last century’s historic democratic transitions, first in Poland and then in South Africa. And today, as we mourn the loss of Nelson Mandela, I am reminded of his extraordinary character and his impact on history—and marvel that I had the opportunity to get to know this dedicated and compassionate man.

In June 1981, I was a member of the Polish delegation at the International Labor Organization (ILO) conference in Geneva. Our worker’s group was headed by Lech Walesa, and we were still enjoying a carnival of freedom and solidarnosc at home. It was then that I was nominated as a member of the ILO’s Anti-Apartheid Committee and my involvement with South Africa began.

Ten years later (after the democratic changes in Poland), I was named Ambassador to South Africa, representing our new Poland in a country going through its own rebirth.

Given the pace of change that took place in the six years spanning my diplomatic mission, I essentially served in two nations. I arrived in a country with apartheid laws. But groundbreaking decisions were beginning to change the landscape. Nelson Mandela was free, and African National Congress (ANC) activists were returning from exile or from underground.

My position—as ambassador for a country that had recently gone through its own liberation struggle—allowed me the opportunity to be present at many critical and dramatic moments that led to the end of apartheid, first free elections and then the inauguration of the world’s most famous political prisoner as president of the country.

In every meeting with Nelson Mandela, in offices and private residences, I was always impressed not only by him and his legend, but also by the warmth of his personality, fine sense of humor and serious dedication to his cause. And it was clear to me that perhaps his greatest contribution to South African history was his commitment to inclusiveness. He said:

“I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

During those decisive years, on a sunny Saturday morning before Easter in 1993, Chris Hani, Communist Party leader and chief of staff of Umkhonto we Sizwe the ANC’s armed wing, was assassinated. The murder of one of the ANC’s most charismatic leaders and hero to radical youth brought the country to the brink of civil war. Poland, and me as its representative in the country, were swept up in the aftermath when it was discovered that Hani’s assassin was a Polish immigrant, Janusz Walus, who had conspired with Clive Derby-Lewis, a senior Conservative Party Member of Parliament (MP).

South Africa held its breath, terrified of the angry explosion that might follow. Nelson Mandela immediately addressed the nation and appealed for calm: “Tonight I am reaching out to every single South African, black and white, from the very depths of my being. A white man, full of prejudice and hate, came to our country and committed a deed so foul that our whole nation now teeters on the brink of disaster. A white women, of Afrikaner origin, risked her life so that we may know, and bring to justice, this assassin. The cold-blooded murder of Chris Hani has sent shock waves throughout the country and the world. … Now is the time for all South Africans to stand together against those who, from any quarter, wish to destroy what Chris Hani gave his life for—the freedom of all of us.”

The shame of having my countryman so violently intervene in the course of South Africa’s history weighed heavily on me. My respect for Mandela only grew with his effort to calm the nation and his reassurance to me that my country and people were not to blame.

Later, after the elections in 1994 the new South African leaders invited me to participate in their efforts to reconstruct the country. For example, I took an active part in discussions to design and launch in 1995 the National Economic Development and Labor Council (NEDLAC). This institution proved to be successful in bringing together government, business, labor and community interests to reach consensus through negotiations on all labor legislation and all significant social and economic legislation. I had many conversations with Nelson Mandela about the council’s formation, and he took great personal interest and involvement in the establishment of the NEDLAC.

I was a privileged witness of the events of one of the greatest sagas of contemporary history. That mission did not end on the day apartheid ceased. Mandela dedicated his life to completing the unfinished work of liberation— psychological, economic and social emancipation. Through his leadership, wisdom and generosity, he launched a real movement for reconciliation in a deeply divided society.

Nelson Mandela will always remain a great historical figure for his decisive contribution to the victorious anti-apartheid struggle and peaceful, miraculous transition in South Africa. I grieve his death and am humbled for having worked with him.