Jun 3, 2025

When Enoch Gyaesayor logs into a digital app each day to begin picking up passengers and drive around Accra, Ghana, he hopes to get a few hour-long trips where he can be paid the daily top amount from Mondays to Fridays. After paying the company’s commission and job-related expenses, he says he makes 150 cedis ($14.64).

Enoch Gyaesayor, an app-based driver in Ghana, connected platform workers together in a union to build strength to improve working conditions.

But most of the time, Gyaesayor and thousands of other digital app drivers and riders are paid even less, and often work up to 16 hours a day, even sleeping in their vehicles to save petrol money going home and to be ready to start working again as quickly as possible. Higher pay on weekends does not reduce the amount of time they must work.

“There is no ‘off’ day for the driver,” Gyaesayor says, noting that he works seven days a week to support himself and his family.

In Ghana and in countries around the world, the Solidarity Center is building strength with platform workers to create a broad-based, global movement in which app-based workers join together to assert their rights, protect their lives and improve working conditions. Unions and worker organizations are making democracy real in workplaces, legislatures and global forums.

Digital Platform Work: A Growing Industry that Undercuts Labor Rights

A rapidly exploding industry, digital platform work now employs between 154 million and 435 million workers in online jobs. While often seen as a flexible job arrangement, digital app-based work is a growing business model that systematically undercuts labor rights and protections and shifts the responsibility of costs to workers.

With support by the Solidarity Center and the CGTP, digital platform drivers formed a union to collectively push for decent work and are now at the ILO in Geneva urging passage of a treaty improving work for platform workers worldwide.

Around the world, consumers depend on digital platform workers—requesting rides from Uber or Bolt, ordering meals from Zomato, receiving groceries delivered from Glovo, or viewing content on a social media platform. The online platform acts as an intermediary between the worker and the employer. For most workers, these jobs are not a “side gig”–they are full-time work.

Yet app-based workers in Ghana and in most countries worldwide are defined as “independent contractors,” and so not covered by national labor laws, such as a country’s minimum wage.

Some 3 billion consumers used online food delivery service—groceries and meals—in 2024. Although global food delivery alone was an estimated $380.43 billion in 2024, the workers transporting the food, driving passengers and moderating online content receive little pay and no safe and healthy working conditions.

Joining Together to Improve Job Conditions

Gyaesayor and other platform workers in Ghana say their top concern is to decrease the percentage of the commission app-based companies require drivers to pay. Uber takes 35 percent from workers’ pay; Bolt, 27.5 percent and Yango up to 25 percent.

The commission fee is only a portion of what workers must pay. With available cars scarce in Ghana, some companies “rent” cars to drivers, adding to a worker’s expense, which also includes mobile phone data, petrol and repairs.

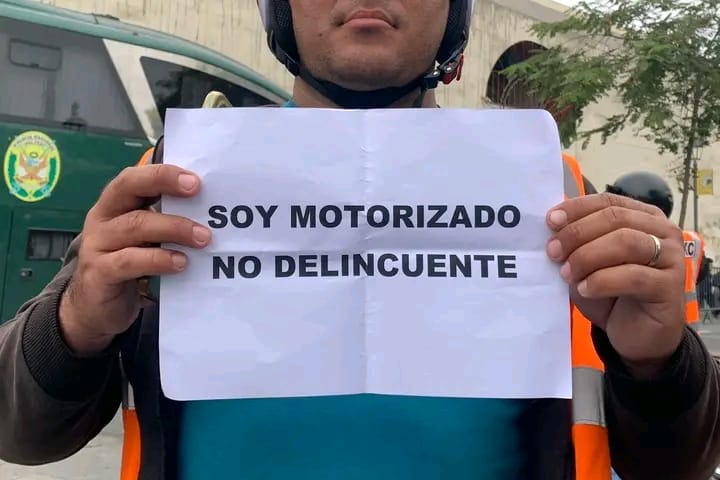

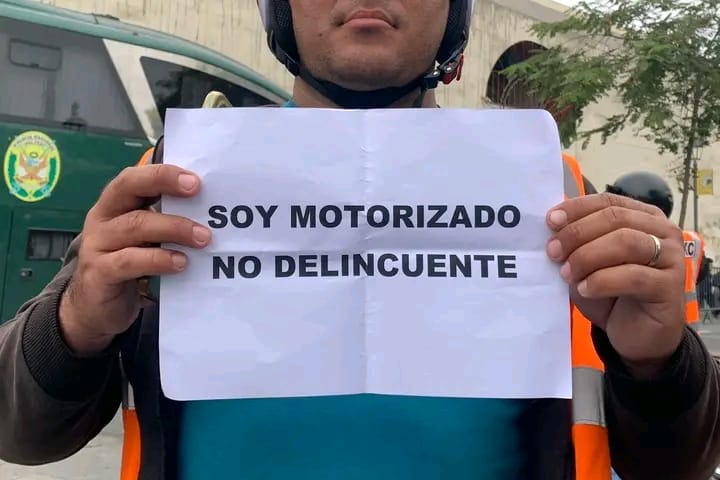

Delivery drivers say they suffer from exhausting workdays, low pay and poor health conditions. Credit: Paloma Luna

Algorithms, which often incorrectly determine distance, time and types of trips offered, further decrease pay. Workers operate at the will of the algorithm and have little recourse to find out why they are locked out of jobs or why kilometers are incorrectly calculated.

“There is a lot of uncertainty and lack of consistency when it comes to rides, how much you will get paid, and so on,” he says.

Gyaesayor, now general secretary of the Digital Transport Workers Union (DTWU), began joining together digital app workers by talking with platform drivers at car parks and shopping malls, urging them to come together to improve their conditions. Several associations representing couriers and other digital workers formed a small association in the Accra and Ashanti regions, By 2023, they created DTWU with a broader reach, joining the Ghana Trades Union Congress (GTUC).

Improve Working Conditions by Joining Together

The digital app union in Ghana, which includes car and bicycle drivers and couriers, is among dozens of platform worker unions around the world, with workers joining together to achieve key goals, including:

- Minimum wage standards.

- Safe working environments.

- Basic social protections such as annual leave, sick leave and retirement benefits.

- Labor law coverage in their countries grants them the same rights as all workers.

To gain these basic rights, workers are engaging in legal action to win unpaid wages, receive compensation for job-related injuries and establish safe working conditions. And, they are mobilizing to improve national and local laws.

Food delivery riders improved pay at FoodPanda in Cebu, Philippines, part of platform workers’ efforts to assert their rights, protect their lives and improve working conditions.

across the globe.

Earlier this year in Mexico, app-based workers campaigned for — and won! — legislative reform that recognizes them as workers and provides access to accident insurance, pensions, maternity leave and company profits. In the Philippines, food delivery riders are improving benefits around the islands. In Cebu, Foodpanda drivers will receive a base fare of 55 pesos (94 cents) and the company will recognize them as employees.

Now, the workers are joining together to take their demands internationally.

Platform Workers Take Global Action

This week, platform work will be formally addressed for the first time on a global stage. At an International Labor Organization (ILO) conference in Geneva, digital app workers and representatives from business and governments are shaping a new international treaty, Realizing Decent Worker in the Platform Economy.

At an ILO conference in Geneva, digital app workers and representatives from business and governments are shaping a new international treaty to ensure decent work for platform workers around the globe.

Digital app workers have been crafting content that delegates will consider, and joining meetings with the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and taking part in a six-day regional workshop in Togo by the ITUC-Africa. Platform workers also are involved in legislative strategies, meeting with their government representatives in advance of the conference.

Charith Attanapola, an app driver in Sri Lanka, met with the country’s minister of labor to convey platform workers’ challenges and discuss ways the government can improve working conditions.

“One of the key takeaways from our discussion was the government’s openness to ensuring decent work across all labor sectors, including app-based transport workers and delivery personnel,” says Attanapola.

Attanapola is part of the Solidarity Center delegation, which includes workers from Brazil, Chile, Ghana, India, Kenya and Mexico. As these workers testify, negotiate and help shape international labor standards that reflect the reality of their work and their demands, they understand the urgency in ensuring how jobs are shaped will determine the future.

In Ghana, where youth unemployment improved from 16.3 percent in 2000 to 5.4 percent in 2024, Gyaesayor knows that gain can be sustained only if decent work is available.

“Platform work has given employment to the majority of the youth; yet those of us who are working are being used like slaves, we get paid barely any salary,” says Gyaesayor. “The government must listen to the union, or things will get much worse; a lot of youth are going to be unemployed.”

Nov 12, 2024

Drivers in Cebu, Philippines, are staying strong as Foodpanda challenges a ruling by a government agency that determined they are employees of the corporation and must receive around $128,000 in lost wages.

Foodpanda is appealing the decision the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) issued in September that required the company to reinstate a 2018–2020 compensation plan that cut driver’s pay by more than half. The ruling also stated that “with no ability to negotiate or alter their fees, riders are more like employees receiving a standard wage rate than independent contractors.”

Foodpanda is challenging a court ruling determining drivers in Cebu are employees who must receive decent pay, safety and health protections and health care.

Credit: Solidarity Center / Miguel Antivola

As with other app-based rideshare and passenger delivery corporations around the world, Foodpanda seeks to classify workers as independent contractors to avoid labor laws requiring pay, safety and health protections, and health care.

“For the five years I’ve worked for Foodpanda, they haven’t offered any type of leave or financial support for medicine,” said Abraham Monticalbo, Jr. The RIDERS-SENTRO (National Union of Food Delivery Riders) member described his experiences working for a company that is not required to adhere to labor protections: “We only get paid when we get an order. If you don’t get bookings, you don’t get paid.”

Foodpanda’s appeal “is just a small amount for the company, yet they’re being stingy with the riders. It’s clear that they don’t really care about our well-being,” Monticalbo said at a union press conference.

Seeking Fairness on the Job

The NLRC ruling on Foodpanda and Delivery Hero Logistics Philippines, Inc., would mean “we can finally receive our earnings that should have long benefited our families and ourselves,” Monticalbo said. “Because of our win, we receive justice.”

The Cebu Foodpanda union chapter of RIDERS-SENTRO has sought fair wages and transparency in the Foodpanda app on scheduling, compensation and suspension. In April, more than 200 Filipino app-based delivery riders took part in a unity ride around Cebu province to protest wage theft.

The Foodpanda app–via the company–sets the rules and is unaccountable to drivers, unilaterally updating acceptance rates, special hours and more. “If you are suddenly tagged for suspension and you follow due process in the app as we were instructed, you will get suspended before they take any action,” said Monticalbo. “Even if you do it right, the suspension is still ongoing. We can’t do anything about it since the tag is still in the system.”

Like Foodpanda, many app-based companies often deploy a “bait-and-switch” tactic, offering benefits to riders only to change the terms later.

“Management treated us well before. If I can compare it to what’s happening now, it’s so far off,” said Monticalbo. Drivers still do their job “because they already left their previous jobs. If they don’t deliver, they don’t earn.”

After the ruling supporting drivers, RIDERS-SENTRO invited the company to enter into discussions for a collective bargaining agreement. With a union, said Monticalbo, the riders are confident of their ability to win their rights on the job even with Foodpanda’s appeal

“Because of the union, we have the fighting spirit for this. We realize our power, our rights.”

Feb 7, 2023

Drivers in Nigeria won the country’s first union covering platform-based workers, a victory that shows it is possible for “unions to organize workers in the gig economy,” says Ayoade Ibrahim, secretary general of the Amalgamated Union of App-Based Transport Workers of Nigeria (AUATWN).

Platform workers in Nigeria join with Labor Ministry officials to finalize recognition of their union, AUATWN. Credit: AUATWN

The Ministry of Labor’s recognition of AUATWN empowers it to have a say in determining the terms and conditions of drivers working for Uber, Bolt and other app-based transportation companies in the country, and covers drivers who deliver food and passengers or engage in other services. The union worked with the Nigeria Labor Congress throughout the campaign for recognition.

In a statement approving AUATWN as union representative of app-based workers last week, the Labor Ministry pointed out that while the freedom to form unions and collectively bargain are internationally protected rights, workers in the informal sector, such as app-based workers, often are not included.

“Today, we are breaking new ground with those in the informal sector who are employing themselves,” the Labor Ministry said. Some 80 percent of Nigerians work in informal sector, as the lack of good jobs—the official unemployment rate is 33 percent, with youth unemployment at 43 percent—leaves workers with few options beyond selling goods in the market, domestic work or taxi driving.

In Nigeria, as in countries around the world, app-based drivers often must work long hours to support themselves and pay for expenses like vehicle maintenance, insurance and car leasing. Excessive hours lead to accidents, says Ayoade.

“I work 15 to 18 hours a day. Long hours working is actually not safe for drivers,” says Ayobami Lawal, a platform driver in Lagos. “That is why you see in the news that the driver had an accident. It is because of fatigue, because there is no time to rest.” Drivers also risk being assaulted and even killed on the job, as platform companies do not screen riders. By contrast, riders have access to drivers’ name and personal phone numbers.

In April 2021, platform drivers and their associations in Nigeria went on strike, demanding that Uber and Bolt raise trip fares to make up for the increased cost of gas and vehicle parts. They also launched a class action suit in 2021 against Uber and Bolt, seeking unpaid overtime and holiday pay, pensions and union recognition. Following the protests, Uber increased fare costs on UberX rides and UberX Share in Lagos, a move that did little to improve drivers’ pay and nothing to improve conditions.

‘We Must Be United’

App-based drivers in Nigeria began seeking union recognition in 2017, after drivers’ income was slashed by 40 percent, says Ayoade, a father of three who that year was forced to drive 10-hour days to make the same income he had previously earned for fewer hours. When Uber and Bolt first launched, drivers were paid enough to work without putting in long hours. But the companies’ price wars to lure passengers and increased driver fees, including commissions up to 25 percent per rider, slashed driver pay.

As the process to register a union with the government dragged, platform worker associations made key gains in mobilizing workers through Facebook, WhatsApp and, most recently, Telegram. The campaign also includes legal action and lobbying Parliament to extend labor laws and social protections to workers in the informal sector.

Three worker associations engaged in the campaign—the National Union of Professional App-based Transport Workers (NUPA-BTW), the Professional E-hailing Drivers and Private Owners Association of Nigeria (PEDPAN) and the National Coalition of Ride-Sharing Partners (NACORP)—last year joined together to form AUATWN.

“We cannot go to war with a divided mind,” says Ayoade. We must be united before we can achieve. The fact that we are united now, we are fierce. We’re trying to involve everybody.”

App-Based Workers Making Gains Worldwide

Unions face unique challenges organizing app-based workers, but by mobilizing members through online apps, unions also have the ability to involve more workers in meetings, education and other opportunities.

“Everybody is included,” says Ayoade. “It’s a more democratic process. We have delegates for unit leadership. If the delegates can’t join for a physical meeting, they can join anywhere.”

Members’ questions can be quickly answered on social platforms and the union operation is more transparent. For instance, he says, members “will see how the money to the union is moving from the app to the account. Every member knows how the money will be used.”

Platform workers in countries worldwide are joining together to better wages, job safety and other fundamental rights guaranteed by international laws. In Kyrgyzstan, gig workers at Yandex Go formed a union and won better wages, while a new report finds that workers on digital platform companies who are pursuing their rights at work through courts and legislation are making significant gains, especially in Europe and Latin America. The Solidarity Center is part of a broad-based movement in dozens of countries to help app-based drivers and other informal sector workers come together. Members of the International Lawyers Assisting Workers Network (ILAW), a Solidarity Center project, have assisted platform workers in many of these cases.

While celebrating the new union, Ayoade also is mindful of the cost some workers paid for a lack of decent work.

“Some of the people we started together with in this campaign, they lost their life along the line,” he says. The lack of insurance or social benefits mean that if drivers are attacked or robbed or even die on the job, they and their family are left all on their own. “They have children, they have parents, who received nothing,” he says.

Although he is bullied and even threatened for his work, Ayoade says such tactics only make him see his efforts are effective. “God gave me the opportunity to help people in this struggle. I am doing something that is improving people’s lives.”