Low Pay, No Support: Sri Lanka Delivery Drivers Seek Worker Rights

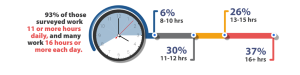

Imagine frequently working more than 11 hours a day—or even up to 16 hours a day—to earn a living. Those hours are what nearly all (93 percent) app-based passenger and delivery drivers say they must work to support themselves and their families in Sri Lanka, according to a new Solidarity Center report.

With 100 Sinhalese and Tamil platform workers surveyed in Colombo, the Sri Lanka capital, and several interviewed, Low Pay, No Support: Delivery Drivers Fight for Worker Rights, examines the struggles of app-based workers who are not covered by hard-won labor laws that mandate a minimum wage, social protections and the right to join or form a union and bargain collectively.

“The money I earn each day is just enough to cover that day’s expenses; most of it goes toward petrol and other vehicle expenses,” says Abdul Illias, who drives passengers for PickMe and Uber. “It’s not sufficient to save for tomorrow, so we must continue working daily to manage for the next day,” says Illias, a 50-year-old father of three who drives passengers (names were changed to protect workers’ privacy).

“The money I earn each day is just enough to cover that day’s expenses; most of it goes toward petrol and other vehicle expenses,” says Abdul Illias, who drives passengers for PickMe and Uber. “It’s not sufficient to save for tomorrow, so we must continue working daily to manage for the next day,” says Illias, a 50-year-old father of three who drives passengers (names were changed to protect workers’ privacy).

While the rapid increase in app-based jobs around the world offers millions of workers additional avenues to earn money, it also creates new opportunities for employer exploitation through low wages, lack of health care and an absence of job safety. The new report identifies these challenges and seeks to ensure platform workers receive decent work.

When the Boss Is an App

With increasing growth in the informal economy, unions, employers and the government should engage in dialogue to ensure worker rights are protected and the countries benefit from the platform economy, Credit: Solidarity Center

None of the drivers or deliverers surveyed or interviewed receive vacation or sick pay. They work long hours and rush between deliveries, risking their safety, because if they do not, the app—via the company—punishes them by lowering pay. When drivers or deliverers are injured, they receive no compensation from their employers and often do not even receive a phone call.

Ayomi, a 38-year-old bicycle delivery driver for Uber Eats, describes the hardships.

“We are on the roads for 10–12 hours a day, and we have no support if we get into accidents,” she says. “In December last year, I had an accident where both my hands were broken. I was bedridden for nearly six months. The company did nothing. The company expects us to be admitted to a private hospital for treatment to receive a larger [insurance] payout, but we can’t do that; we don’t have that kind of money.”

The report also shows how workers are “managed” by algorithmic platforms that determine how they get paid and reported that they sometimes get cheated out of hard-earned wages, as app-based companies reel in workers and then change the rules.

“There is a difference between the actual distance and what the app indicates,” says Jayasinghe Lanka, 52, a seven-year Uber driver.

“I’ve observed that Uber reduces 100 meters for every kilometer. So, when we travel 10 kilometers, it automatically reduces it by one kilometer and shows it as nine kilometers. I joined Uber when it first started in Sri Lanka. They painted a picture of paradise for us. Now, they are exploiting Uber drivers.”

Women passenger and delivery drivers experience even more difficulty, says Chiththara, 41, who supports her mother with her pay as an Uber Eats delivery driver.

“We face health and safety issues, and when we wait for orders, we don’t have a proper facility nearby for sanitary needs. We work during the night, and even though they know a woman will pick up the order, [the app] still sends us to faraway areas. The app selecting main roads instead of smaller ones would improve our safety. They should be more mindful of the roads they choose.”

Delivery and passenger drivers in Sri Lanka are now joining together to form a union—and demand change.

Building Union Strength for Decent Work

Charith Attanapola, who is organizing app-based platform workers in Sri Lanka, says drivers are “working to build strong collective bargaining power to negotiate better terms and conditions.” A key part of drivers’ campaign for fairness is addressing arbitrary and unfair algorithms. Delivery workers suffer from bans from the app, without the right to defend themselves. Among many goals, Attanapola says the union, now with 350 members, plans to advocate and negotiate transparent and fair pricing mechanisms and fair revenue-sharing models.

Attanapola and others members seek to register their union under the name Sri Lanka App Workers Unions and to negotiate contracts that establish reasonable work hours and breaks that protect workers’ health and safety, guard against exploitation and enable app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers to earn decent wages without unreasonably long hours.

“We also will advocate for safe and healthy working conditions, including measures to prevent workplace injuries and harassment,” he said. The union looks to provide solutions “for minimal to zero resting places and sanitation facilities in major cities around Sri Lanka.”

As in countries elsewhere, Sri Lanka’s app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers are classified as freelancers or self-employed workers, an independent worker status outside labor regulation.

App-based workers are seeking coverage by the same labor regulations as protect those in the formal sector, including wage rates, workplace safety and health standards and health coverage.

“I think the government should intervene in this sector and establish regulations. Otherwise, companies like Uber and PickMe will always benefit while we get nothing,” says P. Karunaratna, a driver with Uber and Pick Me.

With increasing growth in the informal economy, unions, employers and the government should engage in dialogue to ensure worker rights are protected and the countries benefit from the platform economy,

Championing worker rights in Colombo and beyond requires workers joining together, Attanapola says.

“We encourage app workers “to join the trade union and participate actively in its activities, like advocating for safe and healthy working conditions.”