Report: With Unions, Workers Experience Less Heat Stress

Workers suffering from heat and other environmental stresses are best able to address the effects of climate change when they do so collectively, such as through their unions—especially when they can bargain collectively, according to Laurie Parsons of Royal Holloway, University of London.

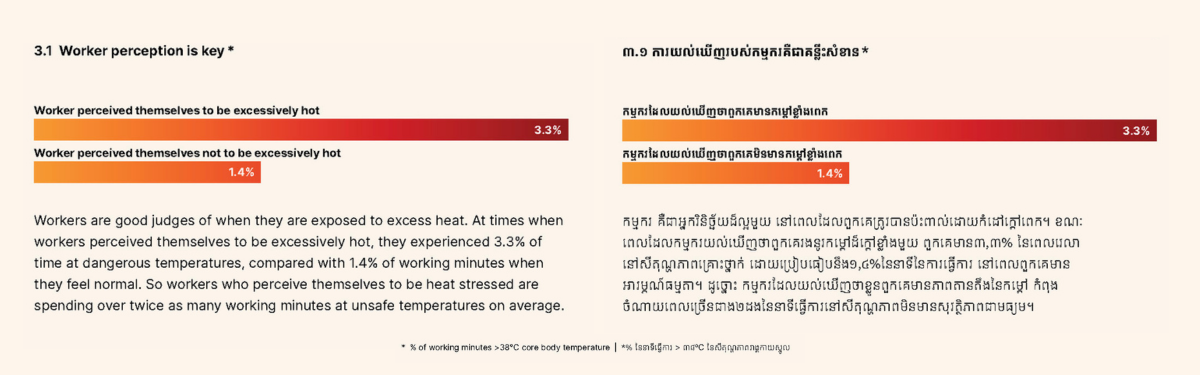

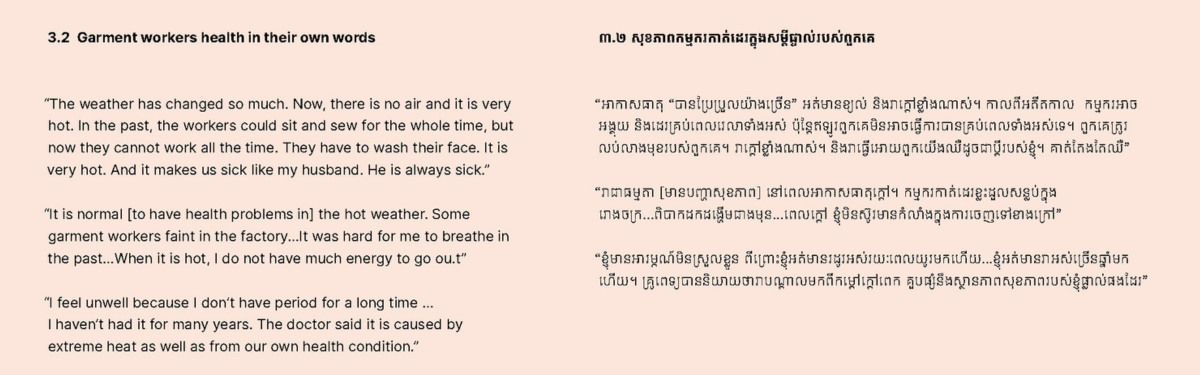

“People are experts on their experience with heat,” said Parsons. “A key neglected area is to adapt to the challenge by acknowledging workers are their own experts.”

Parsons, a Solidarity Center webinar panelist at a United Nations Climate Week event, discussed his new report, “Heat Stress in the Cambodian Workiplace,” which offered innovative research in determining the extent of heat on Cambodian workers.

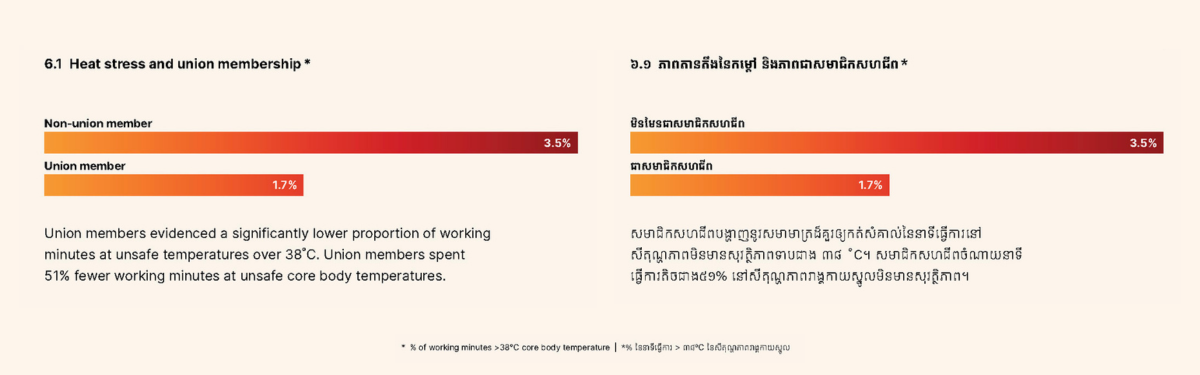

Studying garment workers, street vendors and informal economy workers, the report concluded that unionized workers are better able to mitigate heat stress at work than workers without a union.

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL REPORT

Rising temperatures are significantly affecting workers. More than 70 percent of workers worldwide are at risk from severe heat. While outdoor workers—such as those growing food or building communities—are among those most affected, workers suffer from heat exposure in factories, warehouses and during daily commutes.

The study finds that 55.5 percent of those surveyed report experienced at least one environmental impact in their workplaces in the past 12 months, with air pollution the most common (30.5 percent), followed by extreme heat (25.5 percent) and flooding (9 percent).

The report shows that unionized workers experience half as much heat stress as nonunionized workers, and found that collective bargaining is the most effective form of collectively protecting workers from heat stress.

Workers whose unions bargained over heat experience 74 percent fewer minutes at dangerously high core body temperatures.

As a result, Parsons demonstrates that detailed attention to workers’ bodies to monitor heat “doesn’t cost a lot of money.”

But up to now, heat stress has not been addressed primarily because workers in Cambodia and elsewhere often find it difficult to form a union.

Overcoming Challenges to Joining a Union

“Workers face real obstruction,” said Somalay So, Solidarity Center senior program officer for equality, inclusion and diversity in Cambodia. So shared with panelists the ways in which employers deter workers from forming unions, the difficulties in obtaining union status to negotiate and, when workers win a union, the challenges they face when attempting to negotiate their first contract.

Yet, “despite all these challenges, workers try to achieve smaller agreements,” So said.

She described five innovative heat stress agreements that unions achieved in which a factory agreed to turn on its cooling systems and fans if the factory temperature rose above more than 35 degrees celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit), and assigned mechanics to investigate, suggest and implement other measures if this is ineffective. To ensure companies do not argue that it is not too hot for employees to work, unions have negotiated a clause in which the factory installs a thermometer.

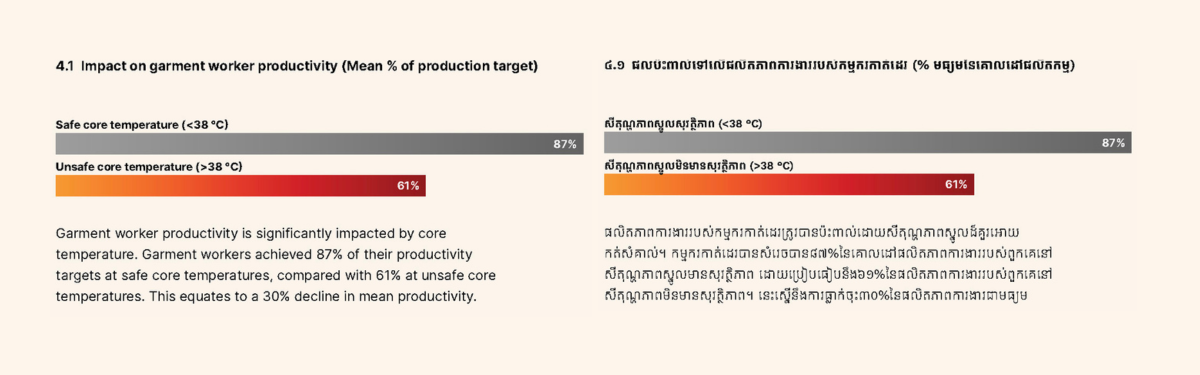

Union leaders also convince employers to protect workers by pointing out that it benefits the bottom line: “It is good for their reputation,” So said, adding that heat not only causes heart and lung problems and lower incomes for workers, it slows workers and their productivity.

Climate Change and Work

Workers experiencing forced migration or who work at informal economy jobs such as food vendors and waste pickers are significantly affected by heat stress because they have little or no formal protection under the law, said Nash Tysmans, organizer for Asia at StreetNet International.

“Some 61 percent of the global workforce are informal workers, yet over half of workers are the most underrepresented” by collective bargaining agreements, she said on the panel. The report found that informal economy workers are in unions experience less exposure to extreme heat.

Women workers are especially vulnerable. In Cambodia, where 85 percent of garment workers are women, heat stress can lead to violence, So said. Heat stress leads to workplace violence and harassment, with employers often responding to falling productivity leading to violence and harassment rather than addressing heat stress issues.

“When their income drops because of climate change, it translates into domestic violence and trafficking,” she said. Workers experiencing violence may leave their area or country to make a living, and can become targets of unscrupulous labor brokers. “Violence and harassment happens more with heat stress. When there is heat stress, women and children are vulnerable even at home.”

Parsons, a professor at Royal Holloway, University of London, and expert on the social, political and economic aspects of climate change, previously researched a 2022 report for the Solidarity Center in Cambodia.

“When people can exercise their rights as workers without repression, not only can they improve their own working conditions, but they can raise standards across workplaces, industries, and across society more broadly,” said moderator Sonia Mistry, Solidarity Center climate and labor justice director.

Said So: “A strong union is when you are able to organize,” so “unions can be at the negotiating table to resolve issues of workers.