Nov 27, 2024

Some 500 factory workers are on strike in Yangon, Myanmar, demanding a return to the job for colleagues who joined them in seeking decent wages and working hours and a workplace free from violence and abuse. Since the strike began in November, more than 50 workers have been fired. On November 22, the company brought in a group of 20 agents from the repressive military junta to threaten workers with physical violence to break the strike.

The members of the Federation of General Workers of Myanmar (FGWM) at the Charis Sculpture factory went on strike in November after the employer did not comply with the terms of a new contract negotiated in July.

The Hong Kong-owned Wise Unicorn Industrial Ltd., owner of Charis Sculpture, has an estimated annual revenue between $10 million and $50 million. Yet in October, when workers protested the employer’s refusal to pay overtime as promised, workers described being followed out of the factory, with two physically attacked.

After the workers went on strike inside the factory November 6 and boosted their list of demands to include dismissal of the director who they say assaulted two workers, the company fired 13 workers, including strike leaders.

“He dragged me and then pushed me with force. I fell down,” one worker told the union. (Names are not used to protect workers’ privacy.)

According to workers, the company says the workers were dismissed for violating the employment contract and “will be dealt with by existing law,” which workers say is an unlawful dismissal.

By November 11, workers were denied entry to the factory and nearly 350 workers remain outside on strike.

Standing Strong Despite Danger

Since the February 2021 military coup, thousands of people have been killed and many more imprisoned, with union leaders especially targeted. Workers—women in particular—took an early lead in the protests against the regime, with the country’s 450,000 garment workers especially active in organizing civil disobedience actions and shutting down factories.

Protests against low wages and poor working conditions remain risky. Yet workers at Charis, a manufacturer of cold-cast bronze, fine porcelain and alloy statues for export to Europe and the United States, are standing strong for their demands. They seek to receive family-supporting pay, including a daily wage of 9,000 Myanmar kyats ($4.28), up from 7,800 kyats ($3.71).

With overtime pay essential for basic support, they call for a 2,000 Myanmar kyats (.98 cents) per hour overtime wage, from the current 1,700 (.81 cents). The workers say many need overtime but the employer does not select them—and overtime pay is “important for workers because the basic wage is not enough,” said one worker.

Women workers especially face physical and verbal harassment, according to the union, which is seeking safe workplace conditions, an end to verbal and physical abuse and an environment with suitable temperature. They also are seeking employer-paid medical care and an end to wage cuts when workers take leave.

Nov 15, 2024

Nearly 2,000 workers at textile factories in Casablanca, Morocco, now can receive decent pay, health care protection and a voice on the job after joining the Moroccan Workers’ Union (UMT) and the federation of textile workers.

“We joined the union primarily to preserve our dignity, which some managers have trampled on,” said one worker, who voted for the union. (Names are not used to protect workers’ privacy.)

All 605 workers in three factories in Casablanca and the majority of the more than 1,000 workers in four additional factories in the area’s large textile industry joined the union.

With a union, workers at textile factories are able to address workplace safety and GBVH. Credit: Hicham Ahmaddouh

Without a union, said one worker, “we couldn’t find solutions to our issues or secure our legal rights, which the company has neglected for more than five years.”

Workers at the leather, textiles, and ready-made garment factories are involved in leather production, sewing, dyeing, supplies and garment manufacturing. They say they often were not paid wages, and received insufficient compensation when often required to work overtime—or engage in fewer hours than specified by the government.

“Wage payments are often delayed, and we only receive them after striking and protesting,” one worker stated when describing conditions before the union representation.

Another worker described being “required to work up to 240 hours a month instead of the legal 191, which should qualify as overtime, yet we receive no compensation.”

Developing Outreach

Achieving success in mobilizing and assisting textile workers to form unions was part of a two-year campaign involving Solidarity Center support in providing data and analysis of key employers, supply chains and other information.

Together with the UMT, the Solidarity Center trained a team led by two women and one man to head up the organizing drive. Over the past year, the team conducted one-on-one outreach at the factories, located in a difficult to access industrial zone. They met with company officials, organized offsite outreach meetings and collected worker stories about their needs and challenges in accessing their fundamental rights.

The outreach effort is essential for expanding the union’s efforts to broaden worker rights.

“Organizing textile workers is crucial to strengthening the union’s capacity to advocate for workers’ rights, secure demands and build solidarity within the Moroccan Labor Union and the National Union of Textile, Leather, and Ready-Made Garment Workers,” said Al-Arabi Hamouk, general secretary of the National Federation of Textile, Leather and Ready-Made Garment Workers.

Textile workers sought improved occupational health and safety in the factories and wanted to ensure the companies’ adherence to labor laws and payment to the country’s social protection fund

“Since 2023, we have been deprived of health coverage because the company hasn’t paid the required contributions, even though they are deducted from our wages,” one worker said.

By forming a union, abuses such as violence and harassment could be addressed, according to a factory worker.

She said in the past, workers suffered “from verbal and sexual harassment by some managers, as well as arbitrary individual and collective dismissals when demand decreases or when we ask for our legal rights.”

“The Solidarity Center played a critical role in the success of the campaign within the textile sector,” said Hamouk. “The organizing team demonstrated the ability to strategize, and address challenges.”

Assisting textile workers in forming unions moves forward their ability to achieve decent wages, safe workplaces and essential health care coverage—and advances their democratic rights to freely form unions.

Said one union member: “We achieved dignity and the freedom to associate, which was previously denied.”

Nov 12, 2024

Drivers in Cebu, Philippines, are staying strong as Foodpanda challenges a ruling by a government agency that determined they are employees of the corporation and must receive around $128,000 in lost wages.

Foodpanda is appealing the decision the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) issued in September that required the company to reinstate a 2018–2020 compensation plan that cut driver’s pay by more than half. The ruling also stated that “with no ability to negotiate or alter their fees, riders are more like employees receiving a standard wage rate than independent contractors.”

Foodpanda is challenging a court ruling determining drivers in Cebu are employees who must receive decent pay, safety and health protections and health care.

Credit: Solidarity Center / Miguel Antivola

As with other app-based rideshare and passenger delivery corporations around the world, Foodpanda seeks to classify workers as independent contractors to avoid labor laws requiring pay, safety and health protections, and health care.

“For the five years I’ve worked for Foodpanda, they haven’t offered any type of leave or financial support for medicine,” said Abraham Monticalbo, Jr. The RIDERS-SENTRO (National Union of Food Delivery Riders) member described his experiences working for a company that is not required to adhere to labor protections: “We only get paid when we get an order. If you don’t get bookings, you don’t get paid.”

Foodpanda’s appeal “is just a small amount for the company, yet they’re being stingy with the riders. It’s clear that they don’t really care about our well-being,” Monticalbo said at a union press conference.

Seeking Fairness on the Job

The NLRC ruling on Foodpanda and Delivery Hero Logistics Philippines, Inc., would mean “we can finally receive our earnings that should have long benefited our families and ourselves,” Monticalbo said. “Because of our win, we receive justice.”

The Cebu Foodpanda union chapter of RIDERS-SENTRO has sought fair wages and transparency in the Foodpanda app on scheduling, compensation and suspension. In April, more than 200 Filipino app-based delivery riders took part in a unity ride around Cebu province to protest wage theft.

The Foodpanda app–via the company–sets the rules and is unaccountable to drivers, unilaterally updating acceptance rates, special hours and more. “If you are suddenly tagged for suspension and you follow due process in the app as we were instructed, you will get suspended before they take any action,” said Monticalbo. “Even if you do it right, the suspension is still ongoing. We can’t do anything about it since the tag is still in the system.”

Like Foodpanda, many app-based companies often deploy a “bait-and-switch” tactic, offering benefits to riders only to change the terms later.

“Management treated us well before. If I can compare it to what’s happening now, it’s so far off,” said Monticalbo. Drivers still do their job “because they already left their previous jobs. If they don’t deliver, they don’t earn.”

After the ruling supporting drivers, RIDERS-SENTRO invited the company to enter into discussions for a collective bargaining agreement. With a union, said Monticalbo, the riders are confident of their ability to win their rights on the job even with Foodpanda’s appeal

“Because of the union, we have the fighting spirit for this. We realize our power, our rights.”

Nov 10, 2024

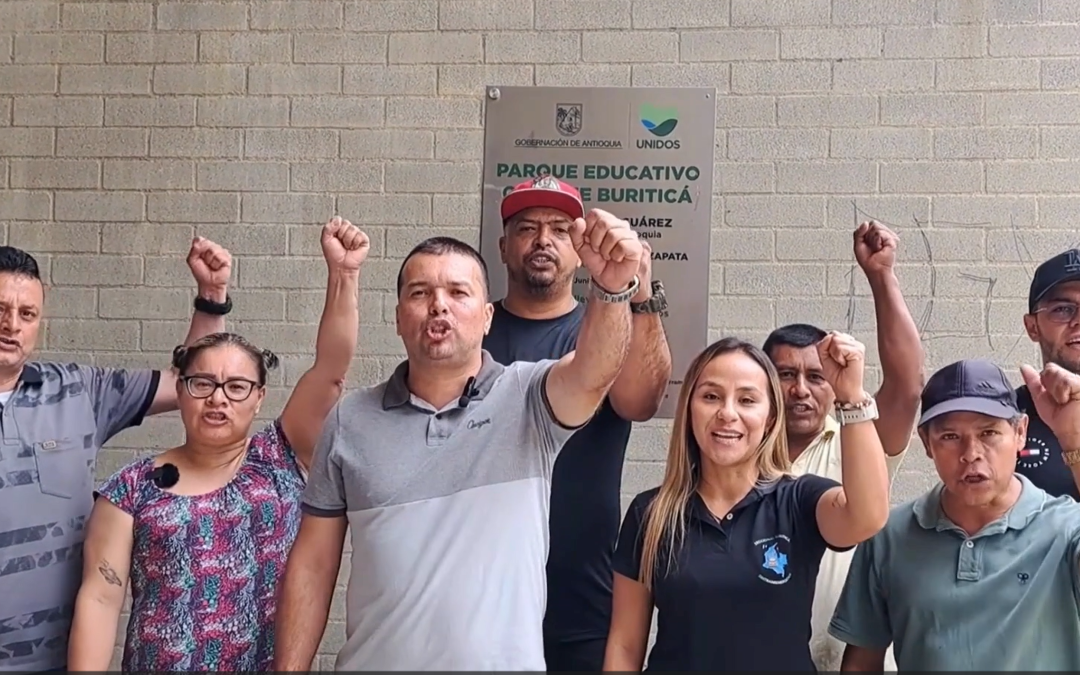

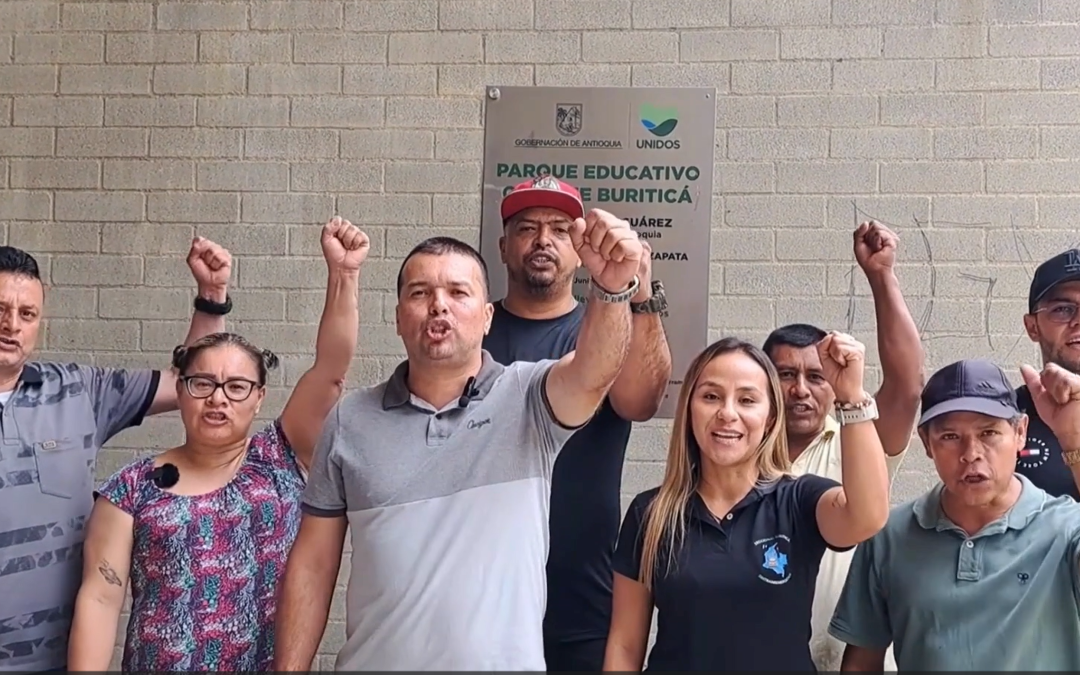

Gold miners in Colombia won their first-ever contract, one that included an annual 3.5 percent wage increase and coverage of all sick leave up to 180 days. The collective bargaining agreement, signed with international corporation Zijin Continental Gold, critically incorporates respect and protection of workers’ rights on the job.

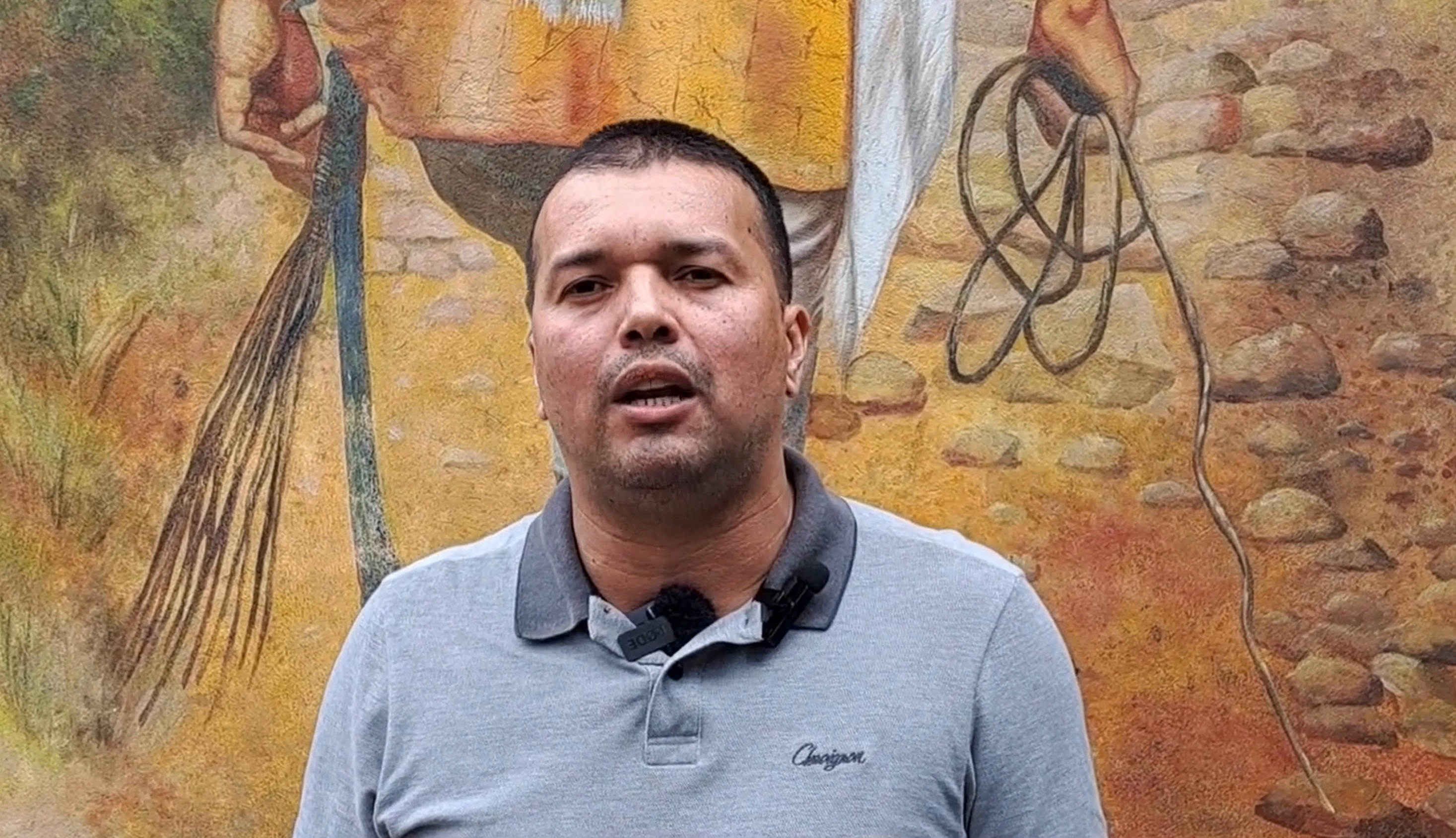

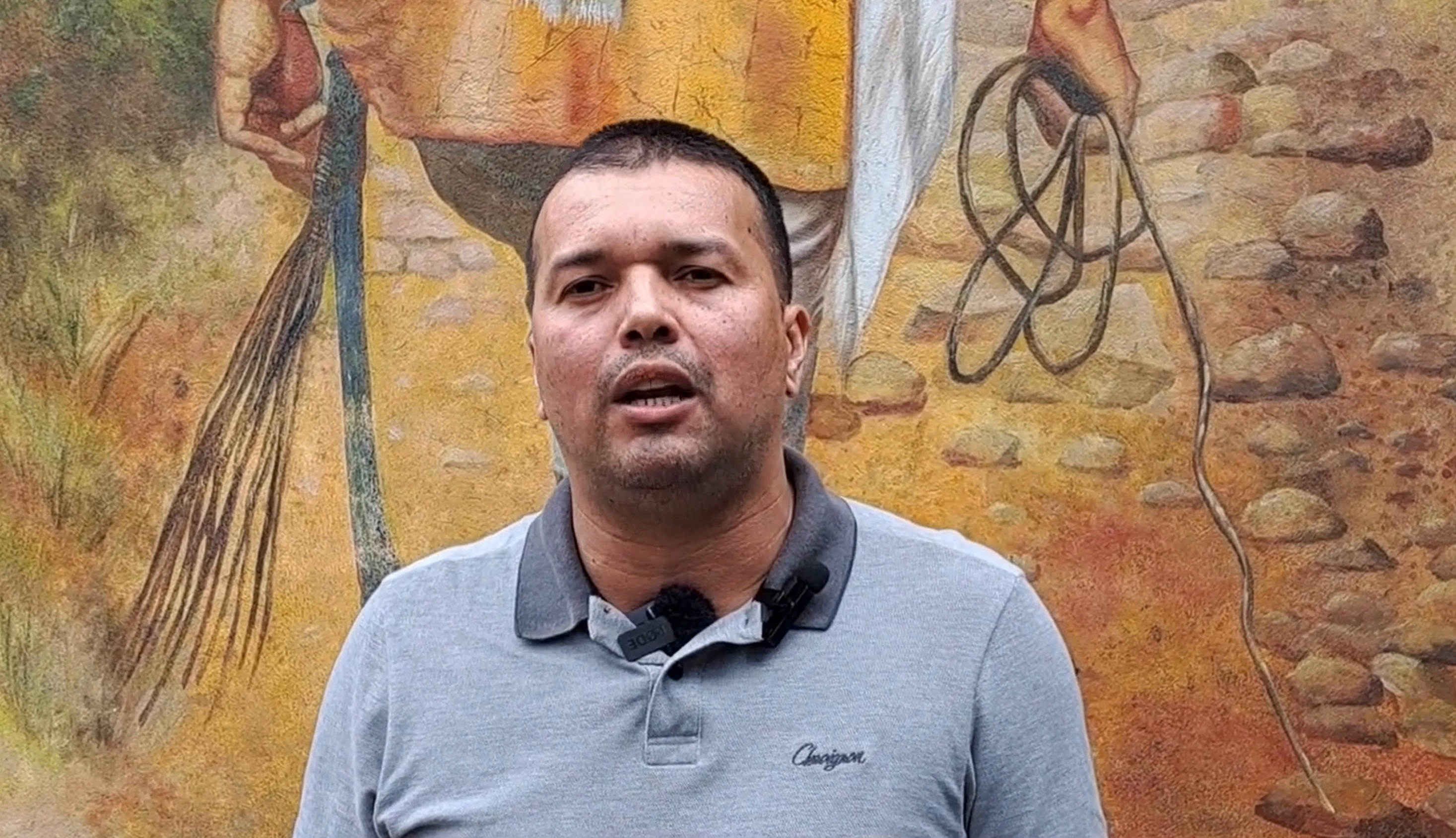

“I’m proud to advocate for workers’ rights and benefits at the Zijin Continental Gold Company. That’s what we seek: to protect workers and ensure they and their families have a better quality of life,” says Sergio Alexander Moreno Moreno, president of Sintramienergética Seccional Buriticá. The union includes more than 450 members at the Buriticá branch and 4,000 members nationwide.

The miners endure difficult conditions with low pay and, over 15 years, had won several arbitration awards. With Solidarity Center support, workers reached the August agreement with the company through negotiation and joint dialogue with the government among representatives of governments, employers and workers on issues of common interest relating to economic and social policies.

The union also negotiated creation of a Labor Dialogue Committee to monitor the contract and ensure its compliance, an essential part of the agreement, says Daniel Esneider Valencia Duque, secretary of collective affairs and labor disputes.

The new contract for gold miners is key to establishing worker rights, says Sergio Moreno, union president.

Achieving Gains with Partnership

To achieve the significant gains for workers, the Solidarity Center engaged with union leadership in a comparative analysis of past arbitration agreements and offered communication support during the bargaining process.

“They helped us draft our fair list of demands, when we reached the collective bargaining stage,” says Cristian Rizo, union general secretary. “The Solidarity Center has greatly supported us in our growth.”

Bolstering skills training and strengthening miners collaboration is part of Solidarity Center’s regional efforts in Brazil, Colombia and Peru, where multinational corporations force miners to endure long days in difficult and often dangerous conditions.

Sharing the benefits of their union in a video, workers describe how they will benefit with the new contract, and urge others to join unions to defend their rights.

“Unity is strength.”

Nov 4, 2024

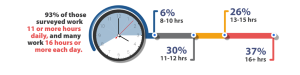

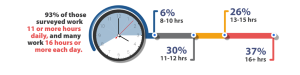

Imagine frequently working more than 11 hours a day—or even up to 16 hours a day—to earn a living. Those hours are what nearly all (93 percent) app-based passenger and delivery drivers say they must work to support themselves and their families in Sri Lanka, according to a new Solidarity Center report.

With 100 Sinhalese and Tamil platform workers surveyed in Colombo, the Sri Lanka capital, and several interviewed, Low Pay, No Support: Delivery Drivers Fight for Worker Rights, examines the struggles of app-based workers who are not covered by hard-won labor laws that mandate a minimum wage, social protections and the right to join or form a union and bargain collectively.

“The money I earn each day is just enough to cover that day’s expenses; most of it goes toward petrol and other vehicle expenses,” says Abdul Illias, who drives passengers for PickMe and Uber. “It’s not sufficient to save for tomorrow, so we must continue working daily to manage for the next day,” says Illias, a 50-year-old father of three who drives passengers (names were changed to protect workers’ privacy).

“The money I earn each day is just enough to cover that day’s expenses; most of it goes toward petrol and other vehicle expenses,” says Abdul Illias, who drives passengers for PickMe and Uber. “It’s not sufficient to save for tomorrow, so we must continue working daily to manage for the next day,” says Illias, a 50-year-old father of three who drives passengers (names were changed to protect workers’ privacy).

While the rapid increase in app-based jobs around the world offers millions of workers additional avenues to earn money, it also creates new opportunities for employer exploitation through low wages, lack of health care and an absence of job safety. The new report identifies these challenges and seeks to ensure platform workers receive decent work.

When the Boss Is an App

With increasing growth in the informal economy, unions, employers and the government should engage in dialogue to ensure worker rights are protected and the countries benefit from the platform economy, Credit: Solidarity Center

None of the drivers or deliverers surveyed or interviewed receive vacation or sick pay. They work long hours and rush between deliveries, risking their safety, because if they do not, the app—via the company—punishes them by lowering pay. When drivers or deliverers are injured, they receive no compensation from their employers and often do not even receive a phone call.

Ayomi, a 38-year-old bicycle delivery driver for Uber Eats, describes the hardships.

“We are on the roads for 10–12 hours a day, and we have no support if we get into accidents,” she says. “In December last year, I had an accident where both my hands were broken. I was bedridden for nearly six months. The company did nothing. The company expects us to be admitted to a private hospital for treatment to receive a larger [insurance] payout, but we can’t do that; we don’t have that kind of money.”

The report also shows how workers are “managed” by algorithmic platforms that determine how they get paid and reported that they sometimes get cheated out of hard-earned wages, as app-based companies reel in workers and then change the rules.

“There is a difference between the actual distance and what the app indicates,” says Jayasinghe Lanka, 52, a seven-year Uber driver.

“I’ve observed that Uber reduces 100 meters for every kilometer. So, when we travel 10 kilometers, it automatically reduces it by one kilometer and shows it as nine kilometers. I joined Uber when it first started in Sri Lanka. They painted a picture of paradise for us. Now, they are exploiting Uber drivers.”

Women passenger and delivery drivers experience even more difficulty, says Chiththara, 41, who supports her mother with her pay as an Uber Eats delivery driver.

“We face health and safety issues, and when we wait for orders, we don’t have a proper facility nearby for sanitary needs. We work during the night, and even though they know a woman will pick up the order, [the app] still sends us to faraway areas. The app selecting main roads instead of smaller ones would improve our safety. They should be more mindful of the roads they choose.”

Delivery and passenger drivers in Sri Lanka are now joining together to form a union—and demand change.

Building Union Strength for Decent Work

Charith Attanapola, who is organizing app-based platform workers in Sri Lanka, says drivers are “working to build strong collective bargaining power to negotiate better terms and conditions.” A key part of drivers’ campaign for fairness is addressing arbitrary and unfair algorithms. Delivery workers suffer from bans from the app, without the right to defend themselves. Among many goals, Attanapola says the union, now with 350 members, plans to advocate and negotiate transparent and fair pricing mechanisms and fair revenue-sharing models.

Attanapola and others members seek to register their union under the name Sri Lanka App Workers Unions and to negotiate contracts that establish reasonable work hours and breaks that protect workers’ health and safety, guard against exploitation and enable app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers to earn decent wages without unreasonably long hours.

“We also will advocate for safe and healthy working conditions, including measures to prevent workplace injuries and harassment,” he said. The union looks to provide solutions “for minimal to zero resting places and sanitation facilities in major cities around Sri Lanka.”

As in countries elsewhere, Sri Lanka’s app-based taxi drivers and delivery workers are classified as freelancers or self-employed workers, an independent worker status outside labor regulation.

App-based workers are seeking coverage by the same labor regulations as protect those in the formal sector, including wage rates, workplace safety and health standards and health coverage.

“I think the government should intervene in this sector and establish regulations. Otherwise, companies like Uber and PickMe will always benefit while we get nothing,” says P. Karunaratna, a driver with Uber and Pick Me.

With increasing growth in the informal economy, unions, employers and the government should engage in dialogue to ensure worker rights are protected and the countries benefit from the platform economy,

Championing worker rights in Colombo and beyond requires workers joining together, Attanapola says.

“We encourage app workers “to join the trade union and participate actively in its activities, like advocating for safe and healthy working conditions.”

“The money I earn each day is just enough to cover that day’s expenses; most of it goes toward petrol and other vehicle expenses,” says Abdul Illias, who drives passengers for PickMe and Uber. “It’s not sufficient to save for tomorrow, so we must continue working daily to manage for the next day,” says Illias, a 50-year-old father of three who drives passengers (names were changed to protect workers’ privacy).

“The money I earn each day is just enough to cover that day’s expenses; most of it goes toward petrol and other vehicle expenses,” says Abdul Illias, who drives passengers for PickMe and Uber. “It’s not sufficient to save for tomorrow, so we must continue working daily to manage for the next day,” says Illias, a 50-year-old father of three who drives passengers (names were changed to protect workers’ privacy).