Apr 2, 2025

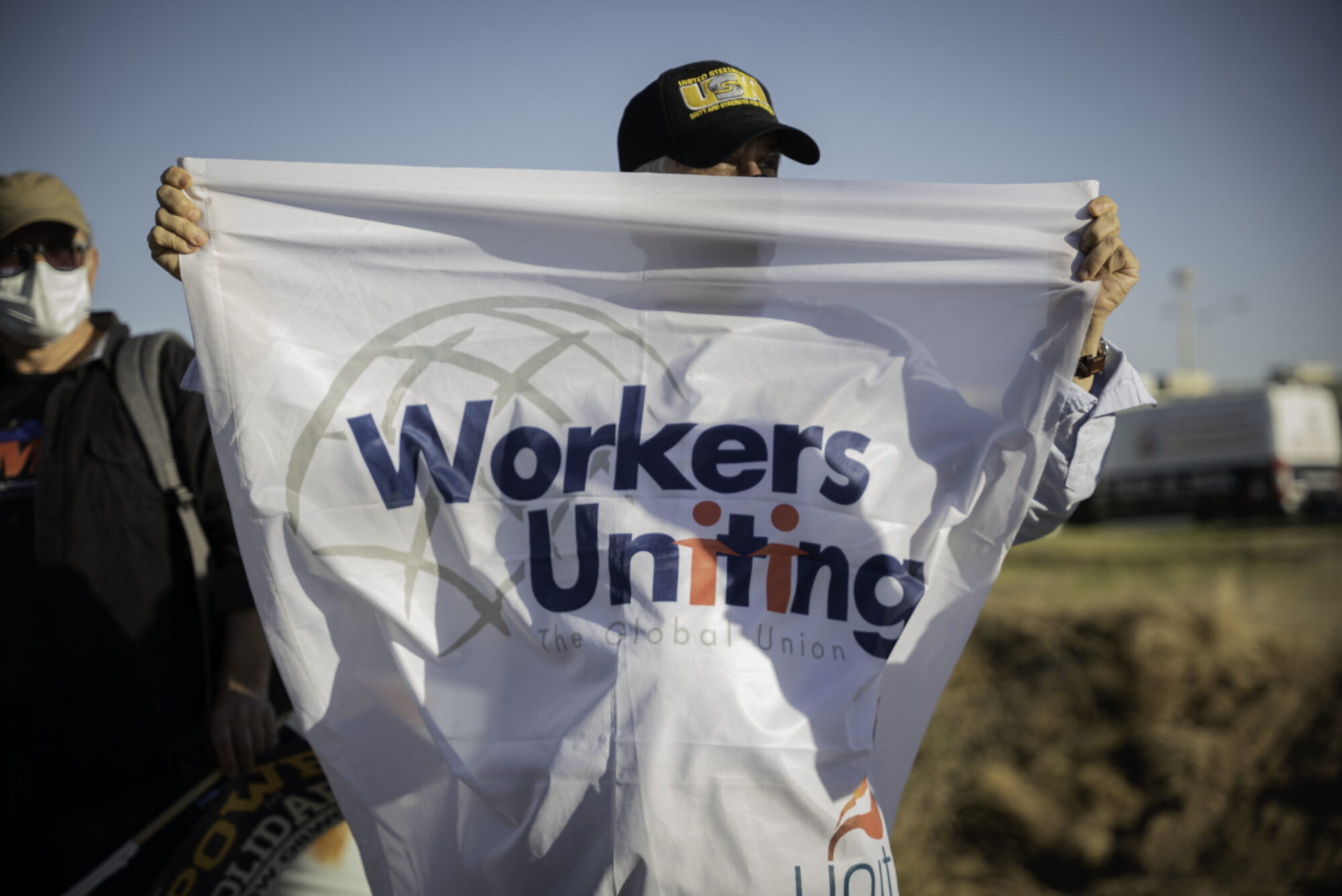

In Tela, Honduras, where the only major employment is palm production, Iván is one of thousands of Hondurans who depend on his job to subsist. But until Solidarity Center training strengthened the workers’ ability to form a union and gain the strength to negotiate with their employer for decent work, they endured long hours and little pay to care for themselves and their families.

“If we have better conditions here, we won’t need to leave the country,” Iván says, noting his goal is for all workers to have decent living conditions and contribute to the country’s economic development. “That’s why we organize, to have better benefits than those offered by the law.”

Without continued Department of Labor (DOL) funding, palm workers in Honduras will lose access to essential training for achieving decent working conditions, making it easier for them to stay in the country.

This week’s termination of program funding for the DOL’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) eliminates how the United States enforces labor standards in trade agreements, protects American workers from unfair competition and combats child labor, forced labor and exploitation around the world.

Over the years, the Solidarity Center has implemented more than a dozen ILAB-funded projects across Latin America, Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe, including in key U.S. trade partner countries like Mexico, Bangladesh, the Philippines and Honduras. Cutting these programs harms U.S. workers, weakens trade enforcement and abandons the global fight for decent work and human dignity.

The Solidarity Center received $78.3 million in DOL funding for projects over the years. They have helped hundreds of thousands of workers build a better life for themselves and their families. Here are some of the workers’ stories in those programs.

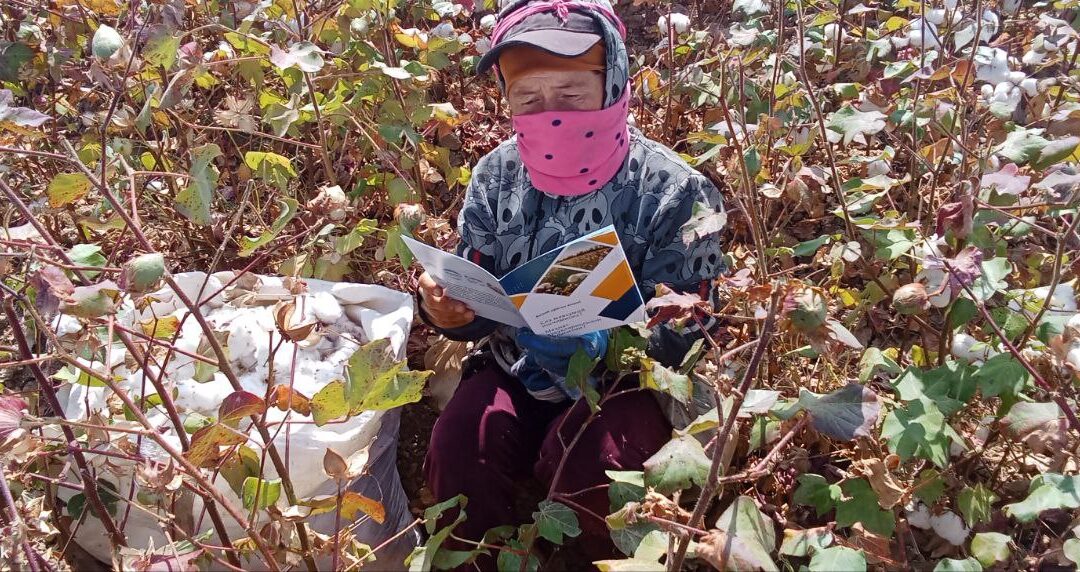

Ending Forced Labor in Uzbek Cotton Fields

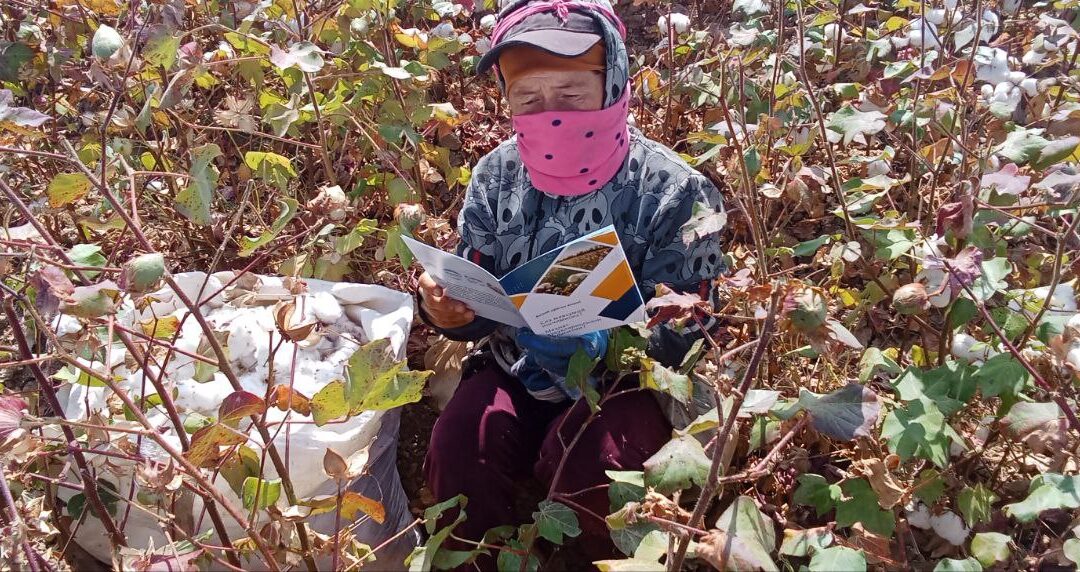

Cotton—in t-shirts, jeans and many household items—is so common, most of us do not give it a second thought. But for decades, millions of people, sometimes including children, were forcibly mobilized by the Uzbekistan government to harvest cotton for state-owned enterprises. Uzbekistan is the world’s sixth largest producer of cotton, producing over 1 million tons annually and employing around 2 million workers.

Cotton—in t-shirts, jeans and many household items—is so common, most of us do not give it a second thought. But for decades, millions of people, sometimes including children, were forcibly mobilized by the Uzbekistan government to harvest cotton for state-owned enterprises. Uzbekistan is the world’s sixth largest producer of cotton, producing over 1 million tons annually and employing around 2 million workers.

The project, now cut with the termination of DOL funding, sought to build on a 15-year effort that successfully eradicated systemic, government-imposed forced labor in Uzbekistan’s cotton supply chain. Through a multi-year global advocacy campaign led by the Cotton Campaign, of which Solidarity Center was a founding member, the government implemented reforms that, in 2021, brought an end to state-mandated forced labor.

To ensure workers who pick cotton continue working in safe conditions, the Solidarity Center signed a groundbreaking cooperative agreement last year with the government of Uzbekistan and other implementing partners to improve working conditions and prevent forced labor.

Ensuring fair labor standards protects U.S. consumers from unknowingly purchasing cotton picked as the result of forced labor, U.S. workers from competing with cotton made cheaper by exploitation and benefits workers in Uzbekistan.

A core priority of the new program would have been ensuring that all cotton sector workers have a written employment contract with enforceable work conditions. Employment contracts ensuring workers receive decent wages in safe conditions are vital, yet absent in many agricultural supply chains. This project aimed to both ensure the reforms to end forced labor in Uzbekistan are durable and help establish Uzbekistan as an alternative sourcing option to forced-labor-produced cotton from other countries.

Better Wages Benefit Mexico, U.S.

Credit: Arturo Left

In Silao, Mexico, Maria Alejandra Morales Reynoso painted auto parts for years alongside other auto plant workers forced to work double shifts with few breaks, even for the bathroom. Through Solidarity Center training and support, Morales and thousands of workers in Mexico formed an independent union, voting out a corporate-supported union that did not operate in their interest.

The union victory “gave people hope, hope that it was possible to represent workers freely,” she says. “We proved it’s possible to get organized and to fight for our rights and to leave behind the fear that we’re going to lose our jobs.”

The ability to improve their employment sparked momentum among other workers, and bolstered the ability of women to take a role in their jobs, as did Morales, now general secretary of SINTTIA, the union workers voted to form.

A reduction in the wage gap between Mexico and the United States, through authentic and transparent collective bargaining, benefits workers in both countries—by improving the wages of Mexico’s workers and disincentivizing companies from relocating from the U.S.to Mexico to exploit artificially low wages.

Over its 25 years of work in Mexico, especially since the enactment of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and its mechanisms for labor rights enforcement, the Solidarity Center’s efforts have benefited more than 42,000 Mexican workers through USMCA resolutions upholding their rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining and obtained over $6 million in back pay and benefits.

In one case, workers at an auto plant in San Luis Potosí won a 30 percent wage increase through a USMCA ruling.

An informed, empowered, and effective agreement across North America is crucial to counter efforts to undermine the promise of shared prosperity for workers in North America. The termination of DOL funding will negatively impact workers in Mexico and the United States.

Decent Wages for 3 Million+ Mine Workers

Ruth Adriana Lopez Patiño, Los Mineros, Julia Quiñonez, CFO, and Mariela Sanchez Casas, Los Mineros, all founders of the “Mineras de Acero” (Women Miners of Steel) training program, participate in a tour of a gold mine during a training in February 2015 on gender equality and women’s leadership. Credit: Los Mineros

In Mexico, where Los Mineros represents more than three million mine workers, the Solidarity Center assisted the union in successfully utilizing the USMCA’s labor instrument (Rapid Response Labor Mechanism) in 2022 to achieve union representation and successfully negotiate a strong bargaining agreement with a 15 percent wage increase.

“Thanks to technical assistance provided by the Solidarity Center funded by DOL/ILAB, we were able to use the Rapid Response Mechanism—a tool that helped us achieve justice,” says Imelda Guadalupe Jiménez Méndez, Los Mineros, secretary of political affairs. “Today our contract is 60 percent more beneficial to the workers thanks to authentic collective bargaining.”

Although the Mexican Supreme Court ruled in favor of the mine workers in 2019, it was only through the assistance of the Solidarity Center engaging in the USMCA that Los Mineros successfully negotiated a groundbreaking salary increase and significantly improved working conditions.

Mine workers in Mexico benefited from key Solidarity Center support. Shutting down Solidarity Center funding for the programs jeopardizes life-changing gains in workers’ wages, benefits and conditions and increases pressure on U.S. workers who must compete with low wages in Mexico.

Safeguarding Job Safety and Health

“Pure drinking water, a first-aid box is mandatory at our workplace, as well as women should be paid like as male co-workers,” says one woman who works at a construction site in Bangladesh.

Basic needs—fresh water, medical supplies—and wages to support her family are now accessible through Solidarity Center training that enabled her union leaders to develop a list that included crucial workplace safety and health protections and successfully negotiate to achieve those goals. In a highly competitive sector, where employers can treat workers as dispensable, such lists are essential tools that workers at a grassroots level can use to raise key concerns.

However, DOL’s termination of grant funding means thousands of construction workers in Bangladesh will not have the impact of basic workplace safety and health protections and will have little ability to receive decent wages.

These are only a few examples of Solidarity Center has benefited workers and their communities through DOL funding. Its termination will silence these efforts and undermine U.S. commitments to American workers and workers worldwide.

Halting Workplace Danger

In the electronics industry in Malaysia, the seventh largest exporter of electrical and electronics products in the world, workers producing the semiconductors used to power a range of consumer products endure hazardous conditions and lack job safety and health protections. They often face hazardous conditions, such as exposure to toxic chemicals, which can cause detrimental health effects, including cancers, respiratory issues, and even reproductive harm, including fertility problems and hazards for pregnant women. Often, they are targets of forced labor.

A new Solidarity Center project, which began in 2024, sought to improve occupational safety and health standards and address workers’ access to social benefits such as social security, compensation for injuries, health care and other labor protections. Many of the workers travel from other countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal, Indonesia, Myanmar and the Philippines and face additional challenges in the workplace.

Solidarity Center training, funded by the DOL, sought to strengthen workers’ ability to take part in their workplace and their union and hold leadership positions to promote safe and healthy work environments by building strong and inclusive unions to effectively address OSH in the workplace. Solidarity Center sought to increase engagement by workers and worker organizations with government officials and employers to negotiate, address, resolve and prevent OSH abuses in the workplace through collective bargaining.

The programs also aim to level the playing field for workers in the United States by ensuring workers around the world are not exploited and abused in the frequent attempts by employers and governments to skirt the law in countries such as those in Asia. But the funding for the Solidarity Center program to address dangerous conditions for workers producing electronics in Malaysia, as with all DOL-funded programs in countries throughout the world, have been terminated.

Oct 7, 2024

World Cotton Day – October 9, 2024: As ubiquitous as cotton is in our everyday lives, the workers who produce and harvest this foundational crop are often invisible. This was long the case in Uzbekistan, where for decades the government forcibly mobilized millions of people, sometimes including children, to harvest cotton for state-owned enterprises. A long-running global advocacy campaign led by the Cotton Campaign, of which Solidarity Center was a founding member, helped push the government to implement reforms that brought that system to an end in 2021.

Ending state-organized forced labor was a major accomplishment, but establishing just and equitable working conditions in the cotton sector is a longer journey. With support from the U.S. Department of Labor, the Solidarity Center is working to put in place building blocks that will allow workers to ensure their rights are protected. The Solidarity Center signed an agreement with the Ministry of Employment and Poverty Reduction of the Republic of Uzbekistan and the project’s co-implementing partner, the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), in December 2022 to begin project work. As the 2023 harvest season gets underway, Solidarity Center and CIPE are working closely with stakeholders in government, civil society and business to work from the field up and from oversight authorities down to build knowledge within the cotton sector about fundamental rights and strengthen mechanisms to ensure those rights are secured.

For the 2023 harvest, this includes:

- In collaboration with the ministry’s labor inspection and legal team, the Solidarity Center and CIPE have prepared and printed more than 10,000 leaflets for distribution to cotton pickers during the ongoing harvest season. These leaflets provide cotton pickers with accessible and comprehensive information about their fundamental rights as seasonal workers under Uzbekistan’s Labor Code. The content covers essential worker protections and includes critical contact information, such as the Labor Inspection hotline and a project-run Telegram channel, where workers can anonymously report violations and seek free legal consultation. The leaflets have been also distributed to groups working in different regions across Uzbekistan to maximize outreach. This initiative plays a crucial role in raising awareness among seasonal workers, ensuring they are informed of their rights and the enforcement mechanisms available to them if their rights are violated. Providing clear and accessible information about legal protections and enforcement channels will be essential to empowering cotton workers to assert their rights, and increased awareness is critical to improving compliance with international labor standards, which is the route to creating a more sustainable and transparent cotton sector.

- The Solidarity Center, in partnership with the Tashkent Mediation Center and the State Labor Inspectorate, successfully conducted a two-day training session October 2–3 in Tashkent aimed at enhancing the capacity of mediators to resolve individual labor disputes. The training, facilitated by a regional expert, introduced participants to mediation as an alternative mechanism for labor dispute resolution. The comprehensive curriculum, a blend of theoretical knowledge and practical exercises, equipped 10 mediators from the Tashkent Mediation Center and Labor Inspection staff with the skills to mediate and effectively resolve individual labor disputes. The head of the Labor Inspectorate emphasized the importance of continued collaboration and capacity building as critical to providing workers in the cotton sector with an effective remedy for labor rights violations.

These harvest-period activities supplement an ongoing rights awareness and education program the Solidarity Center and CIPE are implementing with workers and employers in the cotton sector. A core priority of that program in the coming year will be to ensure that all workers in the cotton sector have a written employment contract with clear, enforceable conditions of work. Employment contracts are vital to healthy labor relations that, unfortunately, are absent in many agricultural supply chains.

Recent reforms in Uzbekistan requiring labor contracts for all workers in cotton production have the potential to help the country distinguish itself as a high-road option for textile sourcing, if those reforms can be implemented and enforced. Developing workplace-level reporting and monitoring systems for workers to verify their rights are being respected, and to seek remedy if they are not, will be an important next step to positioning Uzbekistan as a leader in developing sustainable and just textile supply chains.

Funding is provided by the United States Department of Labor under cooperative agreement number IL-38908-22-75-K, through a sub-award from the Solidarity Center. 100% of the total costs of the project or program is financed with federal funds, for a total of $1,018,814. This material does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Department of Labor, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government.

Jan 8, 2024

A groundbreaking cooperative agreement seeking to improve working conditions and prevent forced labor was signed this week for workers, ‘at all stages of cotton and textile production in Uzbekistan.’ Agreement signatories include U.S.-based Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), employers’ Association of Cotton-Textile Clusters of Uzbekistan, the Solidarity Center and the Uzbekistan Ministry of Employment.

The two-year memorandum of cooperation is the cornerstone of a new CIPE-Solidarity Center project that was launched at a public event in Tashkent in November. By meeting the sector’s need for an effective reporting and grievance remedy system, and providing an education and incentive system supportive to compliance, the project seeks to build on a 15-year effort that successfully eradicated forced labor in Uzbekistan’s cotton supply chain.

The “Enhancing Transparency and Accountability in the Cotton Industry of Uzbekistan” project—which will be implemented by CIPE and the Solidarity Center through activities laid out in the agreement’s accompanying action plan—is funded by the U.S. Department of Labor.

“The Solidarity Center looks forward to working with CIPE and the Cluster Association to support development of a cotton industry in Uzbekistan that is recognized and rewarded in the global marketplace for upholding labor standards at the highest levels,” said Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau at the program launch.

Project goals include to expand stakeholder dialogue to promote transparent market and management standards and employee-oriented accountability systems; establish trust and dialogue among cotton purchasers, producers, workers and the government of Uzbekistan; strengthen Uzbekistan’s cotton supply chain workers’ capacity to identify and effectively resolve labor rights violations through tripartite mechanisms and improved dialogue with employers; improve compliance with international labor standards, including freedom of association and corporate governance provisions; and foster cotton industry sustainability in ways that ensure labor rights are respected and protected.

Under the agreement’s accompanying action plan, program activities will include:

- Developing and piloting worker-led grievance and remedy mechanisms grounded in best international practices for supply chain transparency and management;

- Training workers, managers and employers in the cotton industry on fundamental international standards as defined in core conventions of the International Labor Organization;

- Promoting standards of transparency and commitment to labor rights and good corporate governance by creating a dialogue between stakeholders cotton enterprises, global brands, government agencies and worker representatives.

“We believe that our partnership will support the creation of effective management systems and serves to strengthen social protection, improve labor relations based on international standards and create decent and safe working conditions for workers,” said CIPE Managing Director for Programs Abdulwahab Alkebsi at the program launch.

After years of intense policy advocacy and campaigning, led by Uzbek and international civil society, combined with the Uzbek Government’s political will, state-imposed forced labor is no longer used in the cotton harvest. As a result, in March 2022, the Cotton Campaign ended its call for a global boycott of cotton from Uzbekistan and lifted the Uzbek Cotton Pledge.

May 26, 2023

A milestone convening in Tashkent last week brought together stakeholders from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan government ministries and agencies, non-governmental and civil society sectors, and international organizations as a first step in developing a joint action plan to combat forced labor and advance worker rights in the region. Worldwide, 28 million people were reportedly trapped in forced labor in 2021.

The May 22 conference highlighted labor inspectorates’ role in protecting worker rights and combating forced labor in the region. Solidarity Center supported the event, which was organized in collaboration with “Partnership in Action,” an international NGO network of more than 30 Central Asian organizations, Kyrgyzstan’s Migrant Workers Union’s partner organization “Insan-Leylek” and Uzbekistan’s Istiqbolli Avlod.

“There is a crucial need for regional cooperation in labor inspections, because migration patterns are constantly changing,” says “Insan-Leylek” leader Gulnara Derbisheva.

Recognizing the importance of collective action, the conference hosts provided a forum for representatives of labor inspectorates from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan to share their expertise and experiences within their respective countries. Government representatives from each of those countries reiterated their commitment to labor inspectorates working cooperatively with one another and with the region’s worker rights defenders to fight labor exploitation and promote safer working environments and dignified work for all.

Topics included international standards related to the work of inspectorates, issues surrounding forced labor in Central Asia and the importance of labor inspections given the region’s unique challenges. Participants identified a severe shortage of labor inspectors—Solidarity Center research finds that 250 labor inspectors oversee 280,000 legal entities employing 6.5 million people in Kazakhstan, 30 inspectors oversee thousands of enterprises in Kyrgyzstan and 315 inspectors oversee 578,000 registered entities in Uzbekistan—and discussed restrictions on inspectorates’ effectiveness. Although the International Labor Organization (ILO) standards specify that inspections be conducted without prior notification, all three countries require prior consent and advance notice for inspections and exclude small businesses from inspection mandates. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan are currently considering legislative changes to rectify such loopholes.

“The outcomes of the conference have the potential to transform labor protection, ensuring safer and fairer working conditions for everyone in the region,” says Solidarity Center Europe and Central Asia Regional Program Director Rudy Porter.

According to ILO data, some 2.3 million women and men around the world succumb to work-related accidents or diseases every year, including 340 million victims of occupational accidents and 160 million victims of work-related illnesses. The ILO reports 11,0000 fatal occupational accidents annually in the 12-member states comprising the Commonwealth of Independent States—Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan—but points to “gross underreporting” of occupational accidents and diseases in the region.

Cotton—in t-shirts, jeans and many household items—is so common, most of us do not give it a second thought. But for decades, millions of people, sometimes including children, were forcibly mobilized by the Uzbekistan government to harvest cotton for state-owned enterprises. Uzbekistan is the world’s sixth largest producer of cotton, producing over 1 million tons annually and employing around 2 million workers.

Cotton—in t-shirts, jeans and many household items—is so common, most of us do not give it a second thought. But for decades, millions of people, sometimes including children, were forcibly mobilized by the Uzbekistan government to harvest cotton for state-owned enterprises. Uzbekistan is the world’s sixth largest producer of cotton, producing over 1 million tons annually and employing around 2 million workers.