Nov 12, 2024

Drivers in Cebu, Philippines, are staying strong as Foodpanda challenges a ruling by a government agency that determined they are employees of the corporation and must receive around $128,000 in lost wages.

Foodpanda is appealing the decision the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) issued in September that required the company to reinstate a 2018–2020 compensation plan that cut driver’s pay by more than half. The ruling also stated that “with no ability to negotiate or alter their fees, riders are more like employees receiving a standard wage rate than independent contractors.”

Foodpanda is challenging a court ruling determining drivers in Cebu are employees who must receive decent pay, safety and health protections and health care.

Credit: Solidarity Center / Miguel Antivola

As with other app-based rideshare and passenger delivery corporations around the world, Foodpanda seeks to classify workers as independent contractors to avoid labor laws requiring pay, safety and health protections, and health care.

“For the five years I’ve worked for Foodpanda, they haven’t offered any type of leave or financial support for medicine,” said Abraham Monticalbo, Jr. The RIDERS-SENTRO (National Union of Food Delivery Riders) member described his experiences working for a company that is not required to adhere to labor protections: “We only get paid when we get an order. If you don’t get bookings, you don’t get paid.”

Foodpanda’s appeal “is just a small amount for the company, yet they’re being stingy with the riders. It’s clear that they don’t really care about our well-being,” Monticalbo said at a union press conference.

Seeking Fairness on the Job

The NLRC ruling on Foodpanda and Delivery Hero Logistics Philippines, Inc., would mean “we can finally receive our earnings that should have long benefited our families and ourselves,” Monticalbo said. “Because of our win, we receive justice.”

The Cebu Foodpanda union chapter of RIDERS-SENTRO has sought fair wages and transparency in the Foodpanda app on scheduling, compensation and suspension. In April, more than 200 Filipino app-based delivery riders took part in a unity ride around Cebu province to protest wage theft.

The Foodpanda app–via the company–sets the rules and is unaccountable to drivers, unilaterally updating acceptance rates, special hours and more. “If you are suddenly tagged for suspension and you follow due process in the app as we were instructed, you will get suspended before they take any action,” said Monticalbo. “Even if you do it right, the suspension is still ongoing. We can’t do anything about it since the tag is still in the system.”

Like Foodpanda, many app-based companies often deploy a “bait-and-switch” tactic, offering benefits to riders only to change the terms later.

“Management treated us well before. If I can compare it to what’s happening now, it’s so far off,” said Monticalbo. Drivers still do their job “because they already left their previous jobs. If they don’t deliver, they don’t earn.”

After the ruling supporting drivers, RIDERS-SENTRO invited the company to enter into discussions for a collective bargaining agreement. With a union, said Monticalbo, the riders are confident of their ability to win their rights on the job even with Foodpanda’s appeal

“Because of the union, we have the fighting spirit for this. We realize our power, our rights.”

Oct 1, 2024

Organizing a union of more than 200 factory workers in an economic processing zone is a feat in itself, but doing so in just nine months amid management intimidation proves the power of solidarity.

On September 3, more than 60 percent of rank-and-file workers from Hyde Sails Cebu, Inc., a sail manufacturing company, voted union yes in their certification election, with high hopes of negotiating for better benefits and wage increases.

Lucil T. Loquinario, president of the Progressive Labor Union of Hyde Sails (PLUHS-PIGLAS), said earlier this year, “In a union, you will know the true stand and strength of a person,” adding that, “We want to dispel the myth that unions are bad or illegal.”

Fast forward to today, Loquinario noted constant education and pooling strength from each member as the main drivers of their victory. “It is better that all workers know their right to organize and know what we rightfully deserve as written in law. Since management does not let us know, it is only through this endeavor that I know the due process and defense we have as workers.”

The idea of forming a union came to Loquinario in December last year, when she was inspired by a friend who informed her of her rights as a worker. She started getting curious about the benefits her co-workers could be entitled to, along with the automatic 30-day suspension they are bound to when damages are found on manufactured sails.

Loquinario said their organizing started in January—with education seminars and friendly fireside chats with co-workers through May, when the majority of workers was already pro-union. However, word of a budding union reached management.

Loquinario detailed how management started calling them rebels, even installing a security camera in the workplace canteen a few days before the election date to allegedly intimidate workers who planned to vote union yes. She added that management appealed to the Labor department and accused the newly formed union of vote buying for passing out slices of bread to hungry voters after the election.

“It’s worse now,” she said. “Even with a five-minute lapse in break time, they sent a memo to my co-workers.”

Loquinario detailed how, after the election, management started increasing surveillance and demanding written explanations from workers who returned from break a few minutes late. “It is an unreasonable and unfair labor practice,” she said.

While these actions have caused delays in securing their collective bargaining agreement, Loquinario and the union remain hopeful, stressing the importance of having “lakas ng loob,” a Filipino adage for courage.

“We hope this has a good result where we can achieve our goals as workers in proper communication with management,” she said. “Because my co-workers are there, I have more courage to fight for what is right.”

Sep 4, 2024

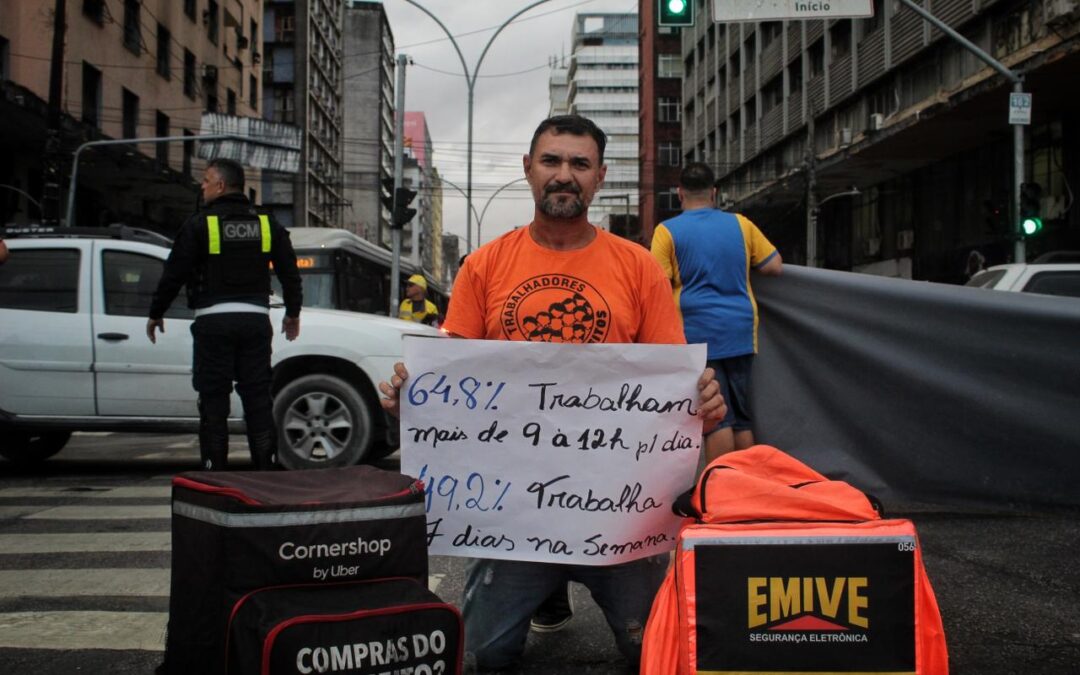

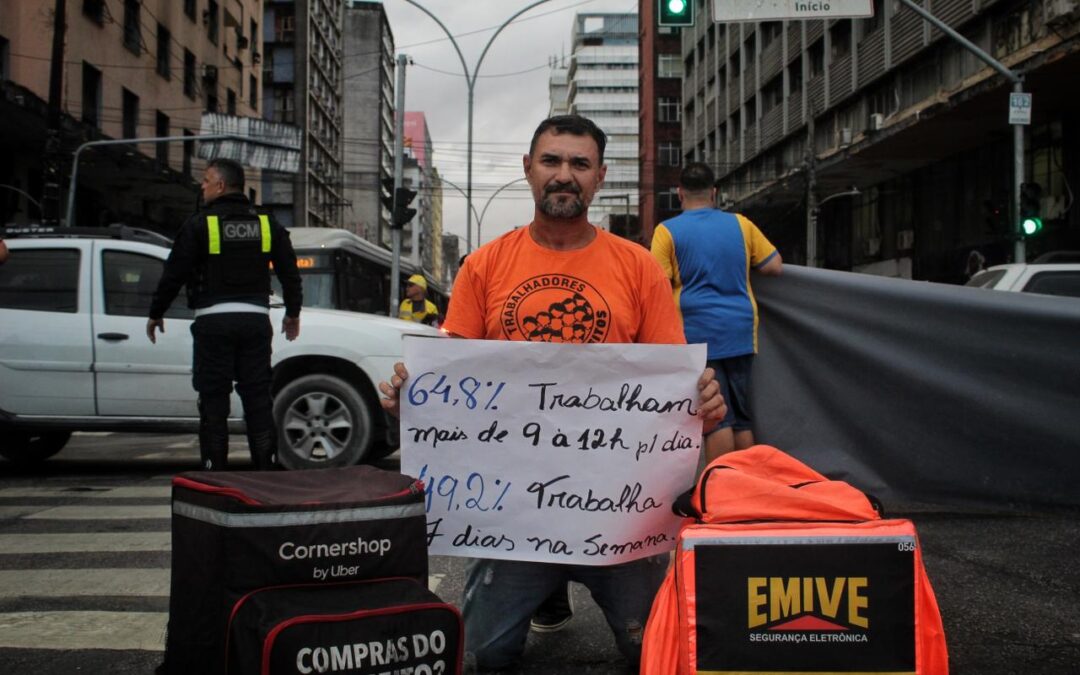

Delivery drivers at iFood in Brazil say they face exhausting workdays, low pay, lack of adequate company support and poor health conditions. In fact, wages that do not cover the cost of living -–or even do not meet the local minimum wage law—force drivers to work longer hours, leading to unsafe or hazardous working conditions and accidents, say experts and app-based drivers.

“There are dangerous conditions on the road with intense traffic that increases the risk of accidents,” says Beethoven Gomes de Oliveira, an app driver in João Pessoa. “This is also true for mototaxi workers. And the app companies don’t care about us workers, they treat us as if we are disposable.”

Delivery drivers say they suffer from exhausting workdays, low pay and poor health conditions. Credit: Paloma Luna

Injuries for the low-wage delivery drivers are on the rise. São Paulo Hospital reports that the percentage of trauma patients rose from 20 percent of motorcycle drivers in 2016 to 80 percent in 2022. Nearly seven people die riding a motorbike on average every day in São Paulo, which health and safety experts attribute to the rapid expansion of food delivery apps.

Workers Fear Poor Treatment Could Expand

Motorcycle and bike drivers are among Brazil’s 1.6 million app drivers and delivery people, a figure that grew rapidly after COVID as workers seek jobs in the informal economy to sustain themselves and their families. And iFood drivers delivered more than 100 million orders in August.

iFood is owned by the Dutch investment company Prosus, a subsidiary of South African tech giant Naspers, and dominates the Brazilian food delivery market with an approximately 80 percent share. iFood anticipates total revenue from its financial arm to rise 52 percent next year-–an amount workers say could easily cover living wages and safer working conditions.

“Pay is very low, not enough to meet our basic needs. For example, maintenance costs are very high, alongside vehicle insurance and food,” says Gomes de Oliveira, leader of the João Pessoa Municipal Delivery Workers’ Commission. We are out on the street all day–12 to 15 hours–to make 100 reales (approximately $18), and even that is a struggle.”

Fabricio Bloisi, iFood CEO, was appointed Naspers joint CEO in July, a move that app-based workers say may spread a business model that destroys their lives.

During a recent shareholders’ meeting, the Shareholder Association for Research and Education (SHARE) raised concerns about the treatment of delivery workers under Bloisi during his iFood tenure. The wider Naspers group owns the food delivery services Mr D Food, Superbalist, Takealot and Delivery Hero (25 percent).

iFood Stalls Negotiations, Basic Democratic Rights

App-based workers, the government and iFood worked together in 2023 on legislation to regulate the digital platform sector—but iFood did not negotiate in good faith with workers during the four-month process, stalling negotiations until recently when the company reached out to the Ministry of Labor.

Even as workers struggled for decent wages and safer working conditions, they say iFood has opposed their democratic right to form a union and stand together in their struggle. A FairWork report finds no evidence the platform ensures freedom of association and the expression of workers’ voice, and no evidence that it supports democratic governance.

Union supporters say they also are targeted by the company’s algorithm, with iFood blocking the accounts of leaders who question their organizing. Delivery drivers have regularly face inaccurate algorithims that cut their pay—or even deny them jobs.

“There are many algorithmic issues: accounts being blocked or deactivated, payments charged incorrectly or to the wrong person, deviations from the route without pay,” says Gomes de Oliveira.

A key part of drivers’ campaign for fairness is addressing arbitrary and unfair algorithms. Delivery workers suffer from bans from the app, without the right to defend themselves.

Company Should ‘Go Beyond Pursuit of Profits’

A 2022 report shows how far iFood was willing to control workers, including monitoring WhatsApp groups, creating fake profiles on social media and infiltrating with an agent. “The Hidden Propaganda Machine of iFood,” found the company hired an auditor specializing in human rights and spent over $1.1 million on research to determine strategies that would not increase the app’s fees during strikes.

As a result of the report and investigations conducted by the Federal Public Ministry and the Labor Public Ministry, iFood and its advertising agencies signed a Conduct Adjustment Term in July 2023. The company agreed it would not increase the fare for trips during a strike—an action delivery workers say often happened, resulting in “strikebreakers.” iFood also is obliged not to intervene directly or indirectly in workers’ organizations, and cannot influence the creation, operation and agendas of associations and unions.

Yet drivers say that iFood continues to violate international treaties, including the right for everyone, without discrimination, to equal pay for equal work and to form and join unions for the protection of their interests.

As the National App Delivery Workers’ Alliance said: “We believe that business leadership should go beyond the pursuit of profits. It should include a commitment to the well-being of workers, ensuring dignified working conditions and promoting practices that respect human rights.

Aug 30, 2024

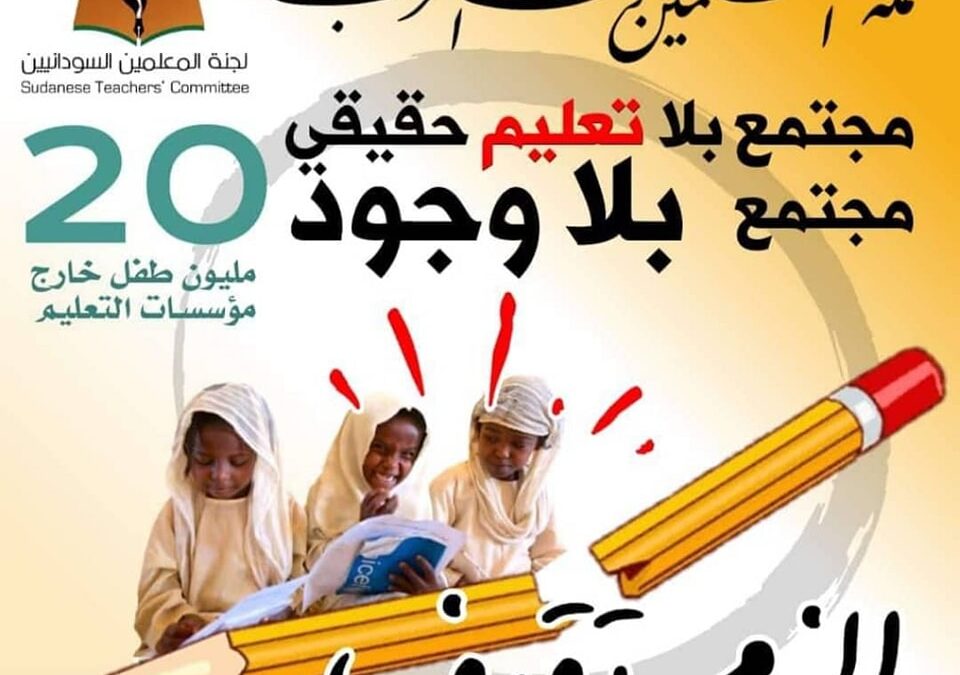

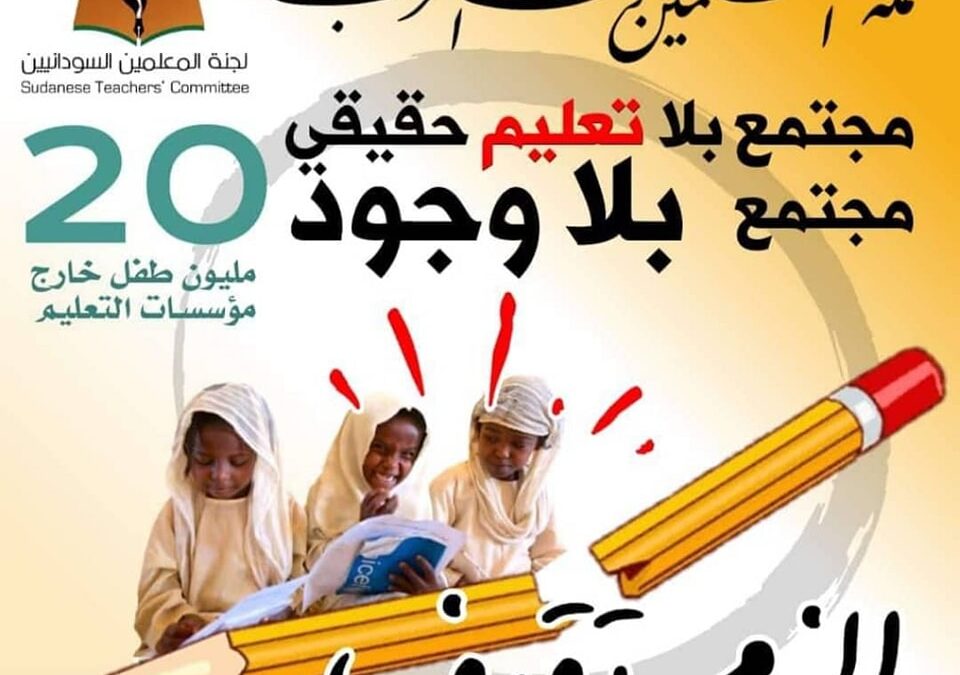

The future of children—their education, development and eventual livelihoods—is an essential reason for ending the war in Sudan, according to the Teachers’ Campaign to End the War.

The Sudanese Teachers Committee, which organized the peace initiative, is part of the Sudanese Civil and Labor Coalition that includes labor and civil society organizations, and is a member of al Taqadum-Sudanese Civil Front movement.

Under the banner, “Teachers are builders of civilizations and advocates of peace,” the Sudanese Teachers Committee points out that no family is “untouched by the destruction caused by the war,” and notes that teachers are the most capable in leading the movement by rejecting the war, with education as the key to achieving peace.

The war in Sudan, which began April 15, 2023, has resulted in the killing, displacement and starvation of millions of people, as well as the destruction of vital public institutions. Nearly 26 million people, half of Sudan’s population, are facing acute hunger. More than 12 million people have been displaced by fighting between a military government and a paramilitary group.

Some 19 million children are out of school, while teachers have not received wages since the start of the war. The committee is serving the public by providing school—at least 6,000 facilities—in shelters.

Reaching Out for Children’s Education

On a Facebook page, which now includes 118,000 followers, the Solidarity Center-backed committee has added dozens of first-person videos by those calling for an end to war, and is campaigning for students’ ability to learn to read and return to school.

On a Facebook page, which now includes 118,000 followers, the Solidarity Center-backed committee has added dozens of first-person videos by those calling for an end to war, and is campaigning for students’ ability to learn to read and return to school.

Committee leaders note that receiving an education is a basic right as stipulated in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, a United Nations treaty signed by Sudan.

The committee also has created a series of posters illustrating the destructive actions of war and how children thrive with education and peace.

“Peace is a means to achieve comprehensive economic and social development, and through it societies advance,” the committee says. “There is no renaissance and development in a country suffering from wars, division and conflicts.”

Aug 20, 2024

With the unexpected shift in Bangladesh political leadership, garment workers say they are hopeful but cautious about the effect on their wages, working conditions and fundamental civil rights, such as the freedom to form unions.

“We hope something positive will happen. However, after the fall of the government, some factories … were prevented from opening in some places,” one factory-level union representative* told the Solidarity Center. “It should not happen.”

After weeks of peaceful student protest were met with deadly government suppression, long-term Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was forced to flee the country on August 4. Students were rallying against a government jobs quota system granting coveted decent work opportunities to family veterans of the 1971 Bangladesh war for independence. More than 600 protestors have been killed.

The economy of Bangladesh, the world’s second-largest garment exporter, depends on garment factories, but producers say customers are concerned about violence and disruption. In 2023, 4 million garment workers contributed 85 percent of Bangladesh’s $55 billion in annual exports.

The recent disruptions, including a government internet shutdown, closed factories, but some garment workers were back to work August 7.

“We only wish our garment sector to thrive,” another worker said. “Our hope is all the factories remain open.”

Lack of Union Freedom Represses Decent Wages, Work

Government repression against workers seeking to form and join unions has prevented garment workers from achieving the living wages and safe working conditions they have sought to achieve, workers say.

With a new government, garment workers seek a crucial change: The ability to freely exert their internationally recognized freedom to form independent unions and bargain collectively for wages and working conditions.

“We want to be able to exercise our trade union rights to the fullest with no pressure from anybody,” says one union leader, who has received threats for efforts to stand up for worker rights.

Although most factories have resumed production, garment workers say their monthly wage still must be increased.

“Many families live on the income of garment workers,” said the union representative.

While many garment workers received wages in July, union leaders tell Solidarity Center that in many other factories, especially those without unions, workers were not paid. In Gazipur, ready-made garments and textile factories demanded their due payment.

Last fall, garment workers who held protests for higher wages were also brutally repressed. The government raised wages to $113 a month, an amount union leaders say does not cover the cost of living, and about half of what workers sought. Multiple labor organizations, including the Industrial Bangladesh Council and Garments Sramik Parishad, said garment workers’ monthly minimum wage must be at least Tk 23,000 a month ($195.81).

Workers said last year’s wage revision did not cover basic needs as “the prices of daily commodities have skyrocketed.” One garment worker who has been on the job for 15 years said, “Usually, our wage is revised every five years. We expect the new government to do that in three years. It will be really beneficial for garment workers.”

* All workers interviewed for this story asked to remain anonymous.

On a

On a