Saving Children, Improving Lives Abroad and in U.S.

In Tela, Honduras, where the only major employment is palm production, Iván is one of thousands of Hondurans who depend on his job to subsist. But until Solidarity Center training strengthened the workers’ ability to form a union and gain the strength to negotiate with their employer for decent work, they endured long hours and little pay to care for themselves and their families.

“If we have better conditions here, we won’t need to leave the country,” Iván says, noting his goal is for all workers to have decent living conditions and contribute to the country’s economic development. “That’s why we organize, to have better benefits than those offered by the law.”

Without continued Department of Labor (DOL) funding, palm workers in Honduras will lose access to essential training for achieving decent working conditions, making it easier for them to stay in the country.

This week’s termination of program funding for the DOL’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) eliminates how the United States enforces labor standards in trade agreements, protects American workers from unfair competition and combats child labor, forced labor and exploitation around the world.

Over the years, the Solidarity Center has implemented more than a dozen ILAB-funded projects across Latin America, Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe, including in key U.S. trade partner countries like Mexico, Bangladesh, the Philippines and Honduras. Cutting these programs harms U.S. workers, weakens trade enforcement and abandons the global fight for decent work and human dignity.

The Solidarity Center received $78.3 million in DOL funding for projects over the years. They have helped hundreds of thousands of workers build a better life for themselves and their families. Here are some of the workers’ stories in those programs.

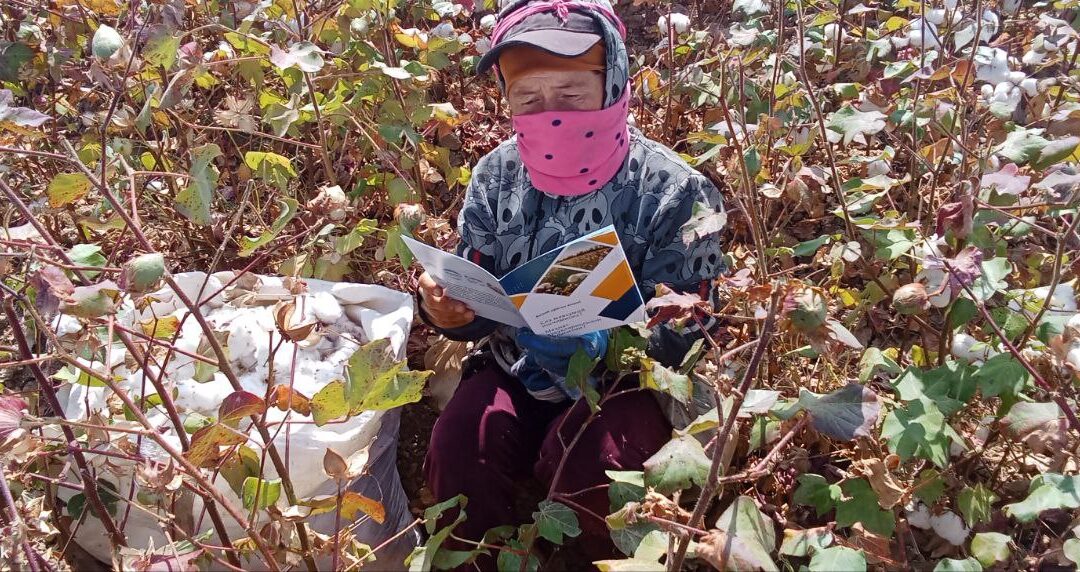

Ending Forced Labor in Uzbek Cotton Fields

Cotton—in t-shirts, jeans and many household items—is so common, most of us do not give it a second thought. But for decades, millions of people, sometimes including children, were forcibly mobilized by the Uzbekistan government to harvest cotton for state-owned enterprises. Uzbekistan is the world’s sixth largest producer of cotton, producing over 1 million tons annually and employing around 2 million workers.

Cotton—in t-shirts, jeans and many household items—is so common, most of us do not give it a second thought. But for decades, millions of people, sometimes including children, were forcibly mobilized by the Uzbekistan government to harvest cotton for state-owned enterprises. Uzbekistan is the world’s sixth largest producer of cotton, producing over 1 million tons annually and employing around 2 million workers.

The project, now cut with the termination of DOL funding, sought to build on a 15-year effort that successfully eradicated systemic, government-imposed forced labor in Uzbekistan’s cotton supply chain. Through a multi-year global advocacy campaign led by the Cotton Campaign, of which Solidarity Center was a founding member, the government implemented reforms that, in 2021, brought an end to state-mandated forced labor.

To ensure workers who pick cotton continue working in safe conditions, the Solidarity Center signed a groundbreaking cooperative agreement last year with the government of Uzbekistan and other implementing partners to improve working conditions and prevent forced labor.

Ensuring fair labor standards protects U.S. consumers from unknowingly purchasing cotton picked as the result of forced labor, U.S. workers from competing with cotton made cheaper by exploitation and benefits workers in Uzbekistan.

A core priority of the new program would have been ensuring that all cotton sector workers have a written employment contract with enforceable work conditions. Employment contracts ensuring workers receive decent wages in safe conditions are vital, yet absent in many agricultural supply chains. This project aimed to both ensure the reforms to end forced labor in Uzbekistan are durable and help establish Uzbekistan as an alternative sourcing option to forced-labor-produced cotton from other countries.

Better Wages Benefit Mexico, U.S.

Credit: Arturo Left

In Silao, Mexico, Maria Alejandra Morales Reynoso painted auto parts for years alongside other auto plant workers forced to work double shifts with few breaks, even for the bathroom. Through Solidarity Center training and support, Morales and thousands of workers in Mexico formed an independent union, voting out a corporate-supported union that did not operate in their interest.

The union victory “gave people hope, hope that it was possible to represent workers freely,” she says. “We proved it’s possible to get organized and to fight for our rights and to leave behind the fear that we’re going to lose our jobs.”

The ability to improve their employment sparked momentum among other workers, and bolstered the ability of women to take a role in their jobs, as did Morales, now general secretary of SINTTIA, the union workers voted to form.

A reduction in the wage gap between Mexico and the United States, through authentic and transparent collective bargaining, benefits workers in both countries—by improving the wages of Mexico’s workers and disincentivizing companies from relocating from the U.S.to Mexico to exploit artificially low wages.

Over its 25 years of work in Mexico, especially since the enactment of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and its mechanisms for labor rights enforcement, the Solidarity Center’s efforts have benefited more than 42,000 Mexican workers through USMCA resolutions upholding their rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining and obtained over $6 million in back pay and benefits.

In one case, workers at an auto plant in San Luis Potosí won a 30 percent wage increase through a USMCA ruling.

An informed, empowered, and effective agreement across North America is crucial to counter efforts to undermine the promise of shared prosperity for workers in North America. The termination of DOL funding will negatively impact workers in Mexico and the United States.

Decent Wages for 3 Million+ Mine Workers

Ruth Adriana Lopez Patiño, Los Mineros, Julia Quiñonez, CFO, and Mariela Sanchez Casas, Los Mineros, all founders of the “Mineras de Acero” (Women Miners of Steel) training program, participate in a tour of a gold mine during a training in February 2015 on gender equality and women’s leadership. Credit: Los Mineros

In Mexico, where Los Mineros represents more than three million mine workers, the Solidarity Center assisted the union in successfully utilizing the USMCA’s labor instrument (Rapid Response Labor Mechanism) in 2022 to achieve union representation and successfully negotiate a strong bargaining agreement with a 15 percent wage increase.

“Thanks to technical assistance provided by the Solidarity Center funded by DOL/ILAB, we were able to use the Rapid Response Mechanism—a tool that helped us achieve justice,” says Imelda Guadalupe Jiménez Méndez, Los Mineros, secretary of political affairs. “Today our contract is 60 percent more beneficial to the workers thanks to authentic collective bargaining.”

Although the Mexican Supreme Court ruled in favor of the mine workers in 2019, it was only through the assistance of the Solidarity Center engaging in the USMCA that Los Mineros successfully negotiated a groundbreaking salary increase and significantly improved working conditions.

Mine workers in Mexico benefited from key Solidarity Center support. Shutting down Solidarity Center funding for the programs jeopardizes life-changing gains in workers’ wages, benefits and conditions and increases pressure on U.S. workers who must compete with low wages in Mexico.

Safeguarding Job Safety and Health

“Pure drinking water, a first-aid box is mandatory at our workplace, as well as women should be paid like as male co-workers,” says one woman who works at a construction site in Bangladesh.

Basic needs—fresh water, medical supplies—and wages to support her family are now accessible through Solidarity Center training that enabled her union leaders to develop a list that included crucial workplace safety and health protections and successfully negotiate to achieve those goals. In a highly competitive sector, where employers can treat workers as dispensable, such lists are essential tools that workers at a grassroots level can use to raise key concerns.

However, DOL’s termination of grant funding means thousands of construction workers in Bangladesh will not have the impact of basic workplace safety and health protections and will have little ability to receive decent wages.

These are only a few examples of Solidarity Center has benefited workers and their communities through DOL funding. Its termination will silence these efforts and undermine U.S. commitments to American workers and workers worldwide.

Halting Workplace Danger

In the electronics industry in Malaysia, the seventh largest exporter of electrical and electronics products in the world, workers producing the semiconductors used to power a range of consumer products endure hazardous conditions and lack job safety and health protections. They often face hazardous conditions, such as exposure to toxic chemicals, which can cause detrimental health effects, including cancers, respiratory issues, and even reproductive harm, including fertility problems and hazards for pregnant women. Often, they are targets of forced labor.

A new Solidarity Center project, which began in 2024, sought to improve occupational safety and health standards and address workers’ access to social benefits such as social security, compensation for injuries, health care and other labor protections. Many of the workers travel from other countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal, Indonesia, Myanmar and the Philippines and face additional challenges in the workplace.

Solidarity Center training, funded by the DOL, sought to strengthen workers’ ability to take part in their workplace and their union and hold leadership positions to promote safe and healthy work environments by building strong and inclusive unions to effectively address OSH in the workplace. Solidarity Center sought to increase engagement by workers and worker organizations with government officials and employers to negotiate, address, resolve and prevent OSH abuses in the workplace through collective bargaining.

The programs also aim to level the playing field for workers in the United States by ensuring workers around the world are not exploited and abused in the frequent attempts by employers and governments to skirt the law in countries such as those in Asia. But the funding for the Solidarity Center program to address dangerous conditions for workers producing electronics in Malaysia, as with all DOL-funded programs in countries throughout the world, have been terminated.