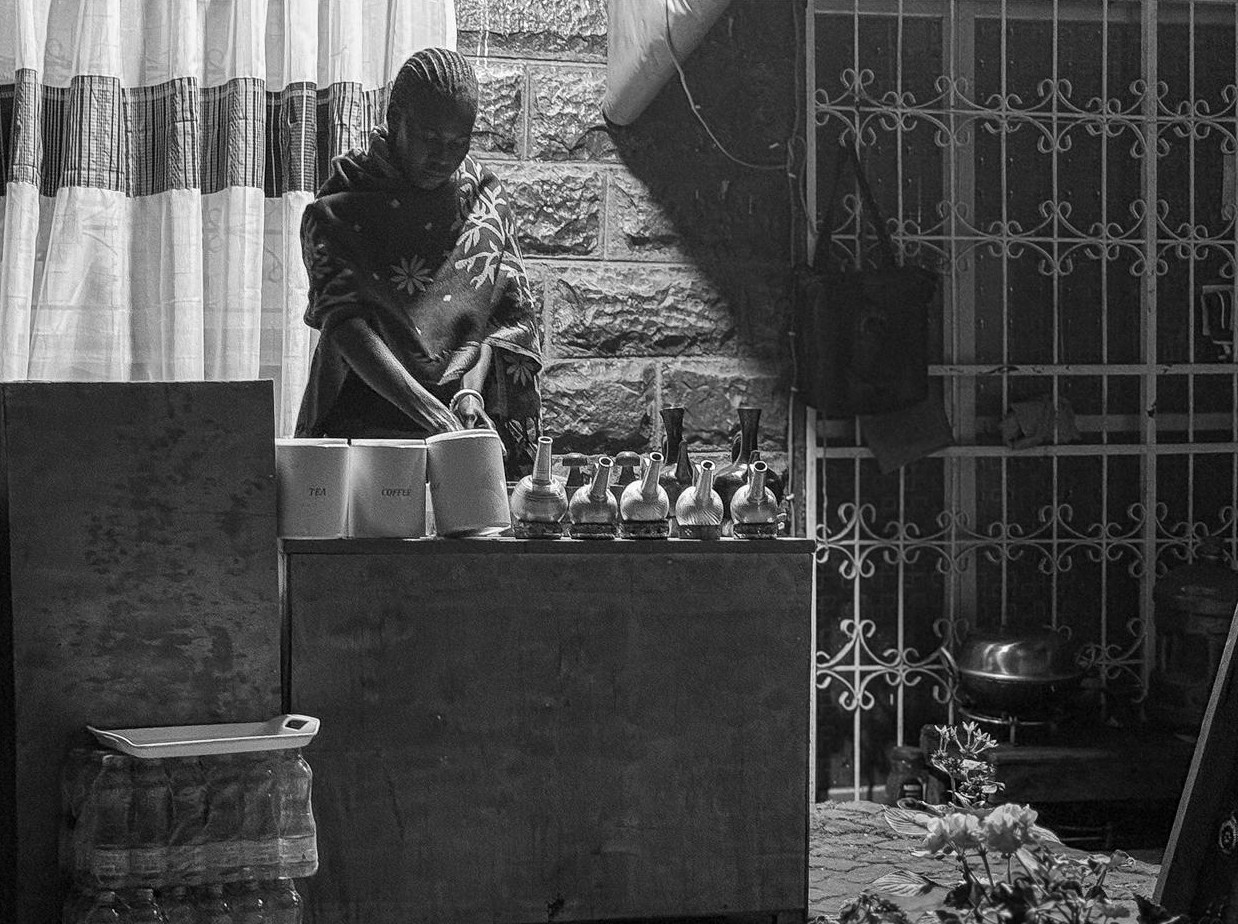

Each day as Yusriya starts work in her tarabiza in northern Sudan, she sets up the roadside stand with a few pots, a stove, plastic or wooden chairs, and hot beverages such as tea, coffee, ginger, hibiscus and other herbal drinks.

“It was hard at first, but when I see my kids eating because of my work, I feel proud,” said Yousriya, who supports a family of 11.

Yet after a 12-hour day, her income ranges between 15,000 and 20,000 SDG ($25-$30), which barely covers monthly rent (250,000 SDG / $416).

“We need an extra 300,000–500,000 SDG monthly ($500-$832) to live with dignity and manage emergencies or sickness,” she said.

Awadeya Mahmoud, a tea seller in Kenya, is among many workers who needed to move from Sudan during the war to support themselves and their families. Credit: Solidarity Center / Hana Abubaker

Roadside stands where people sit to drink tea are common. Yet tea sellers, who are primarily women, often work long hours for little pay in part because of harassment from government agents forcing them to pay “fines,” damage equipment they must pay to replace or because they have to relocate their stands—often to another city.

As the war continues in Sudan, more and more workers must support themselves in the “informal economy”—jobs not in traditional places such as offices and transportation.

Food vendors, like Yusriya, and domestic workers form a cornerstone of the popular economy yet remain excluded from legal protection and are routinely subjected to forced evictions, arbitrary fines, confiscations, harassment and restrictions on forming unions.

Crafting Tools Workers Can Use to Build Better Lives

To address the steep municipal licensing fees that threaten tea sellers’ livelihoods and exclude them from local decision-making, the Solidarity Center is formalizing an agreement between tea sellers and local governments that improves safety and health and provides the freedom tea sellers need for better wages.

The agreement outlines tea sellers’ commitment. Local governments that sign on will designate specific areas where tea sellers can sell tea and provide work permits or licenses to protect them from harassment by authorities.

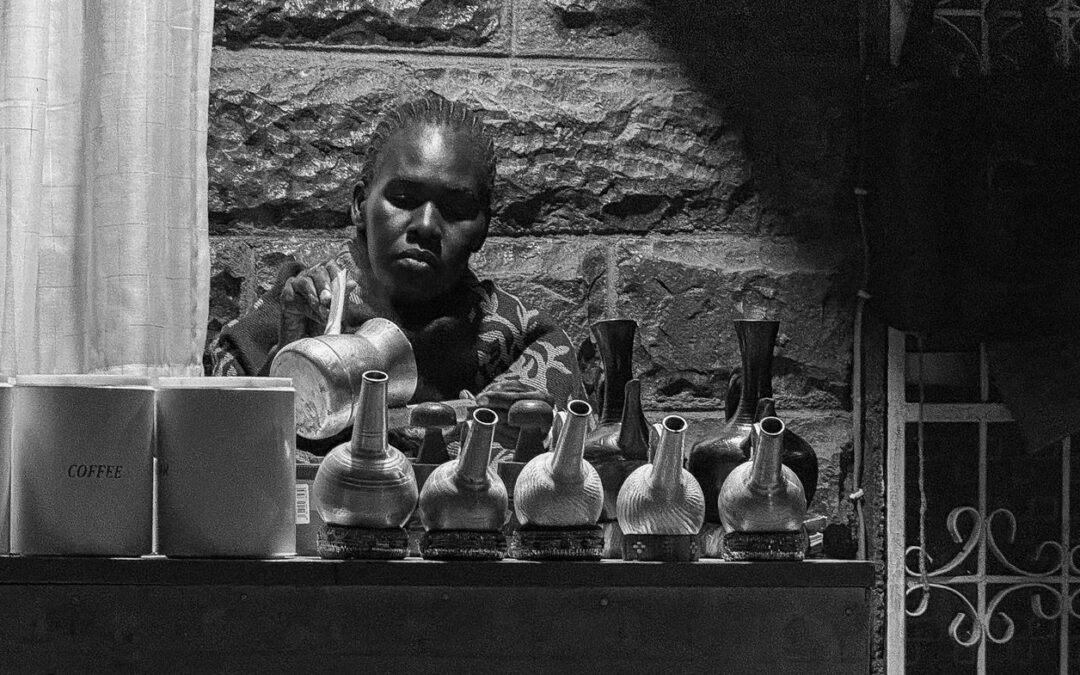

Khadmallah begins selling tea and coffee at 6 a.m. Credit: Solidarity Center / Hana Abubaker

The agreement “will end illegal fines and raids, and give me a fixed place to work,” said Saadiya Mohamed Ahmed Fadl, a tea seller who works daily from 4 a.m. to 7 p.m.

It also ensures tea sellers have access to health care. “Health insurance is vital,” says Yousriya. Workers will be enrolled in the government subsidized medical insurance program and receive access to microfinance funds, enabling them to improve their work and income.

The Trade Union of Tea Sellers and Street Food Vendors, established before the outbreak of the current war, represented an important attempt at organizing. But war disrupted union activity and the Solidarity Center’s efforts to establish agreements with municipalities are key to gaining recognition and reducing harassment at the local level.

In ongoing negotiations, the Solidarity Center is making steps to establish work agreements that provide legal recognition and improve security and fair treatment for tea and food vendors, an essential step toward safeguarding their livelihoods in Sudan’s fragile economic context.

Achieving Legal Protection

With assistance from the country’s legal aid organization in drafting the agreement, the Solidarity Center has crafted a model that can be used across the country. The Solidarity Center is creating agreements in 16 localities in three states, and has now connected with the prime minister and minister of social development to pursue similar accords with the other 15 states.

In securing legalized status and comprehensive legal protections for tea vending as a recognized economic activity, the agreement advances the Solidarity Center’s goals to help workers secure fundamental freedoms-– fair wages, safe workplaces and the right to form associations and unions.

The Solidarity Center also is seeking to register the tea sellers’ association.

Through unions, workers gain the tools, confidence and networks to lead the change they need on their own terms—a goal Yousriya says will provide collective strength to advance. “Forming a union allows me to get a bank loan to expand my business and offers protection,” she said.

In the legal agreement’s first formal violation report that highlighted recent abuse and restrictions tea sellers face in River Nile and Khartoum states, the government committed to take concrete action to protect their human right to work and uphold their dignity.

The Solidarity Center is also advocating for their legal recognition and inclusion in Sudanese labor law and is providing legal aid, rights training and social protection awareness to ensure workers have the tools to stand up for their rights, build stable communities and strengthen democracy.

The agreements and legal success mark a critical milestone in building institutional accountability and opening channels of dialogue between informal workers and state authorities. They also represent an important precedent for ensuring that women working in the informal economy are treated with fairness and respect under Sudanese law.

Establishing a First-Ever Contract for Domestic Work

Domestic workers—who care for children and clean houses—typically also must live in their employers’ homes six days each week, and have no contract with their employer covering wages, hours or working conditions. In Sudan, where some 100,000 make their living as domestic workers, the vast majority are women and girls from low-income or displaced backgrounds.

Together with a legal consultant, the Solidarity Center developed a detailed contract template covering wage payment, work conditions, health access, annual leave, rest periods, accommodation for live-in workers and breastfeeding and prayer breaks.

The Solidarity Center also is seeking to register their association so they can better organize, collectively bargain their work conditions and wages and ensure the agreement and the contract are implemented.

Emtithal Abdo, who supports nine people with her job as a domestic worker, says the contract “raised awareness about our rights-–how to get fair wages that match the nature and effort of the job, and knowledge of basic rights (such as health care and education). It helps balance worker rights and responsibilities, and promotes the right to organize and have a safe and healthy work environment.”