As a hairdresser in Kaduna State in northwest Nigeria, Tina Danbaba is among workers in the country’s “informal economy”—street vendors, small-scale manufacturers and salon workers—who comprise 92 percent of the workforce. With few or no job protections, women like Danbana not only experience economic instability and low wages, but sexual and physical harassment and violence.

Danbaba wanted workers to be able to support their families without fear—so she helped create the Federation of Informal Workers’ Organizations of Nigeria (FIWON). Through FIWON, the first network of its kind in the region, she connected with others to increase their awareness of workplace violence and harassment in shops and at food stands, and advocated for a safe working environment. Danbaba also often identified cases of abuse.

With support from the Solidarity Center through a project funded by the Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB), Danbaba and others were providing the tools and support for women to know their rights and stand up for themselves. Real change. But their efforts were halted after ILAB, part of the Department of Labor (DOL), terminated funding in March as part of the administration’s slashing of foreign aid and international spending. Six months later, Danbaba is no longer able to document workplace violence and harassment or provide services to survivors and vulnerable workers.

“For women here, it was not about luxury, it was about dignity, survival and courage to start speaking without fear,” Danbaba said. “To take this project away is to push us back into the shadows of exploitation.”

‘For Us, a Loss that Cannot Be Recovered’

The abrupt and unprecedented termination of ILAB funding for Solidarity Center, which Solidarity Center has challenged in a lawsuit, programs in Nigeria and Liberia severed a lifeline for women to gain skills to achieve a safe work environment. And because ILAB programs also operated globally, the impact was far wider.

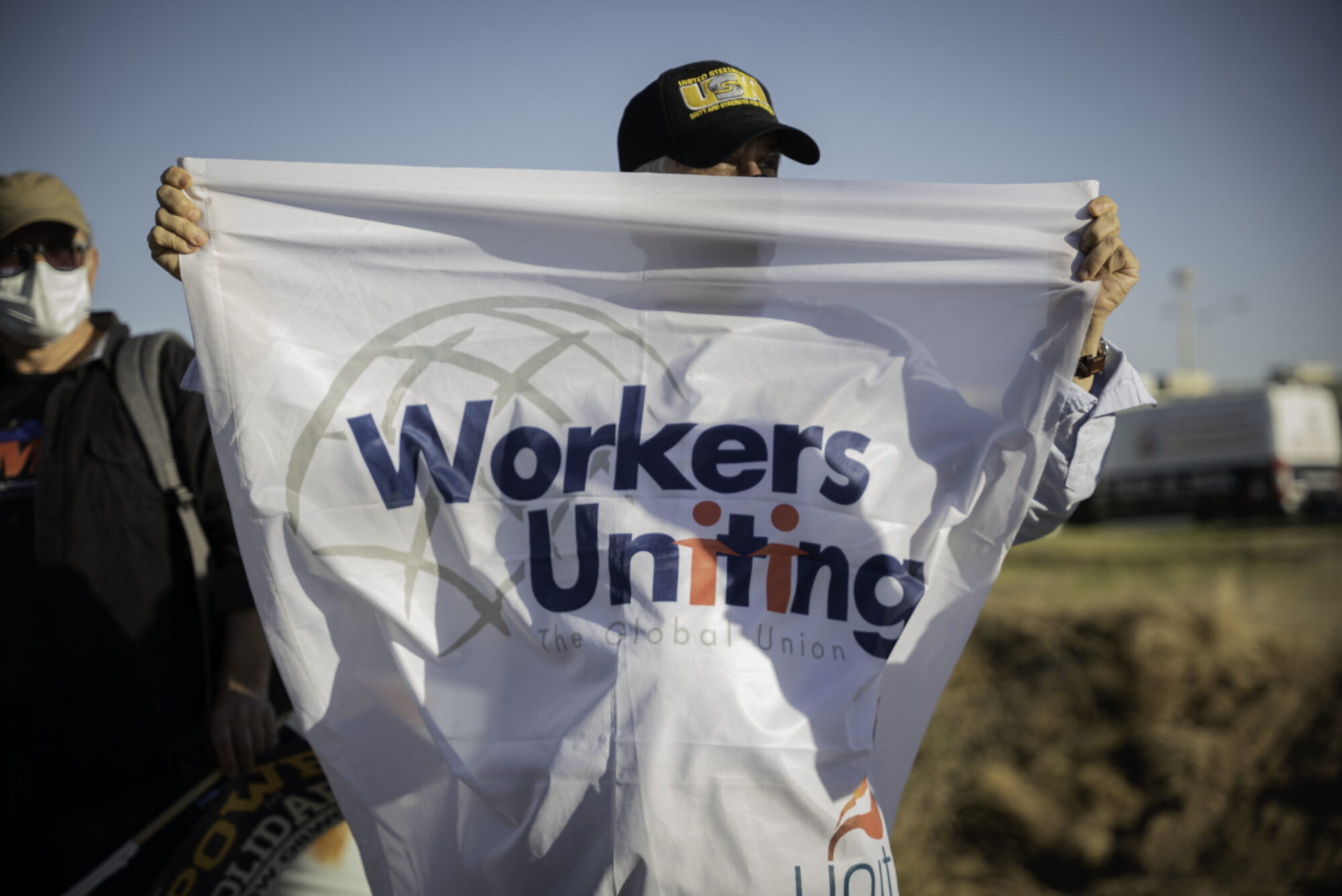

The Solidarity Center received ILAB funding for work in 16 countries and implemented labor rights programs with key U.S. trade partners such as Mexico, Bangladesh, the Philippines and Honduras. Credit: Arturo Left

But in abolishing funding for programs in countries around the world, the move also did even more: It eliminated one of the ways that the United States enforces labor standards in trade agreements, protects American workers from unfair competition and combats child labor and forced labor and exploitation of vulnerable workers around the world.

The Solidarity Center, which received ILAB funding for work in 16 countries, implemented labor rights programs with key U.S. trade partners such as Mexico, Bangladesh, the Philippines and Honduras. These programs helped workers gain collective strength to negotiate decent wages with their employer, improve safety, combat labor abuses and uphold trade commitments.

“The Solidarity Center’s efforts for tea workers improved our lives in many ways,” said Sumon Kumar Tanti, a union organizer among tea workers in Bangladesh.

“Without organized communication, strong knowledge and consistent guidance from the Solidarity Center, our bargaining power is growing weaker every day. This is a loss that we, as tea workers, have no way to recover from on our own.”

Six months after the end of ILAB funding, workers describe how they benefited from trainings and legal assistance to address safety at the workplace, access unpaid wages and build awareness of basic legal rights on the job—and what it means when they no longer can attain these fundamental democratic rights.

Holding Employers Accountable, Not Suffering in Silence

For many of us, drinking a cup of tea is a regular part of the day. Picking the leaves that will make tea is how hundreds of thousands of Bangladeshi workers, mostly women, support their families.

Families often spend their lives living in and working on tea estates, including Bashonti Devi, 40, who, with her husband, picks tea leaves to support their three daughters and son. Credit: Solidarity Center / Gayatee Arun

In Sreemangal, in the northeastern part of Bangladesh, workers leave their tiny, company-provided tin homes and walk long distances across rolling green fields to pick tea leaves for export to the United States and other countries. To meet their daily quota, typically 55 pounds, they will receive $1.55 per day.

Several years ago, after the Solidarity Center began connecting with tea pickers in Sreemangal, they received basic workplace rights for the first time, including a daily hour-long lunch break and access to a medical facility.

“Our community has been historically marginalized and denied basic rights for generations,” said Sreemati Bauri. Vice president of the Juri Valley and Tea Worker in Patharia Tea Garden, Bauri is a tea estate field supervisor and union leader.

“Participating in Solidarity Center’s training gave us the confidence to raise our voice—especially we, the women,” said Bauri. “That knowledge gave us the courage to speak up about our working conditions.”

Tea pickers had access to legal assistance and training provided by the Solidarity Center, which fostered a sense of empowerment and hope among the more than 100,600 workers.

“The Solidarity Center brought legal consultation right to our courtyards, which gave us a safe space to overcome fear, lack of resources and finally seek help,” said Tanti, a field supervisor and organizing secretary for the Rajghat Tea Garden. “Because of this, we could hold employers accountable instead of suffering in silence.”

The termination of funding to enable tea pickers to build a better life “has greatly affected us,” said Bauri. “It has become much harder to maintain the confidence and unity we were starting to build.”

The same story is unfolding elsewhere.

Workers, Business Benefit in the Republic of Georgia

In 2013, the election of a new government in the Republic of Georgia also brought the return of the country’s Labor Inspectorate. The office had been abolished in 2006, a move that contributed to an estimated 74 percent increase in worker deaths, many in mining and construction.

With Solidarity Center support, young workers have been engaged in the democratic process, such as improving their workplaces. Credit: GTUC

While the Labor Inspectorate oversees labor safety, workers in Georgia were unaware of their right to safety on the job and many other workplace basics.

To ensure they knew their rights and how to engage with the Labor Inspectorate’s office, the Solidarity Center, collaborating with the Georgia Trade Unions Confederation (GTUC), reached hundreds of workers in areas with a long history of workplace accidents and fatalities. Workers in mining, construction and heavy industry also took part in trainings to become workplace-level job safety and health experts and assist workers in contacting the Labor Inspectorate when an accident or injury occurred on the job.

“For the GTUC, its collaboration with the Solidarity Center, along with its ongoing support over the years, has been crucial in safeguarding the rights of Georgian workers and strengthening their organizations,” said Raisa Liparteliani. A GTUC general counsel and vice president, Liparteliani is also an executive member of the Georgian Bar Association.

Tamar Ansiani, an organizer with a labor union in Georgia, points to the engagement of young workers. She notes that with Solidarity Center support, she and others “have been fighting successfully for labor rights in different workplaces, including awareness-raising activities that stimulated thousands of young workers to fight for their rights.”

Lawyers for the Solidarity Center provided hundreds of in-person consultations, engaged with thousands of cases via hotline and launched hundreds of legal cases.

“During a seven-year period, with the help of Solidarity Center-funded attorneys, we won more than $12 million for workers via court decisions and collective bargaining,” said Giorgi Diamsamidze, leader of the Agrarian Trade Union/GTUC.

Both unions and businesses viewed empowering the country’s Labor Inspectorate as a path to overall economic growth and modernization. The funding termination ended the work between Georgia’s trade unions and business associations, one that corresponded to positive changes in the country’s labor laws and renewed efforts to better integrate Georgia into bilateral trade networks pointing toward Europe and North America.

As Liparteliani summed up: “The termination has had a significant negative impact on thousands of workers, particularly vulnerable groups, and has considerably weakened the means to protect their rights.”

Brazil Platform Workers: A Voice to Improve Jobs

In Brazil, where traditional employment offering job security and decent wages is decreasing, millions of workers in the country have turned to the “gig economy,” often becoming passenger and delivery drivers to earn a living.

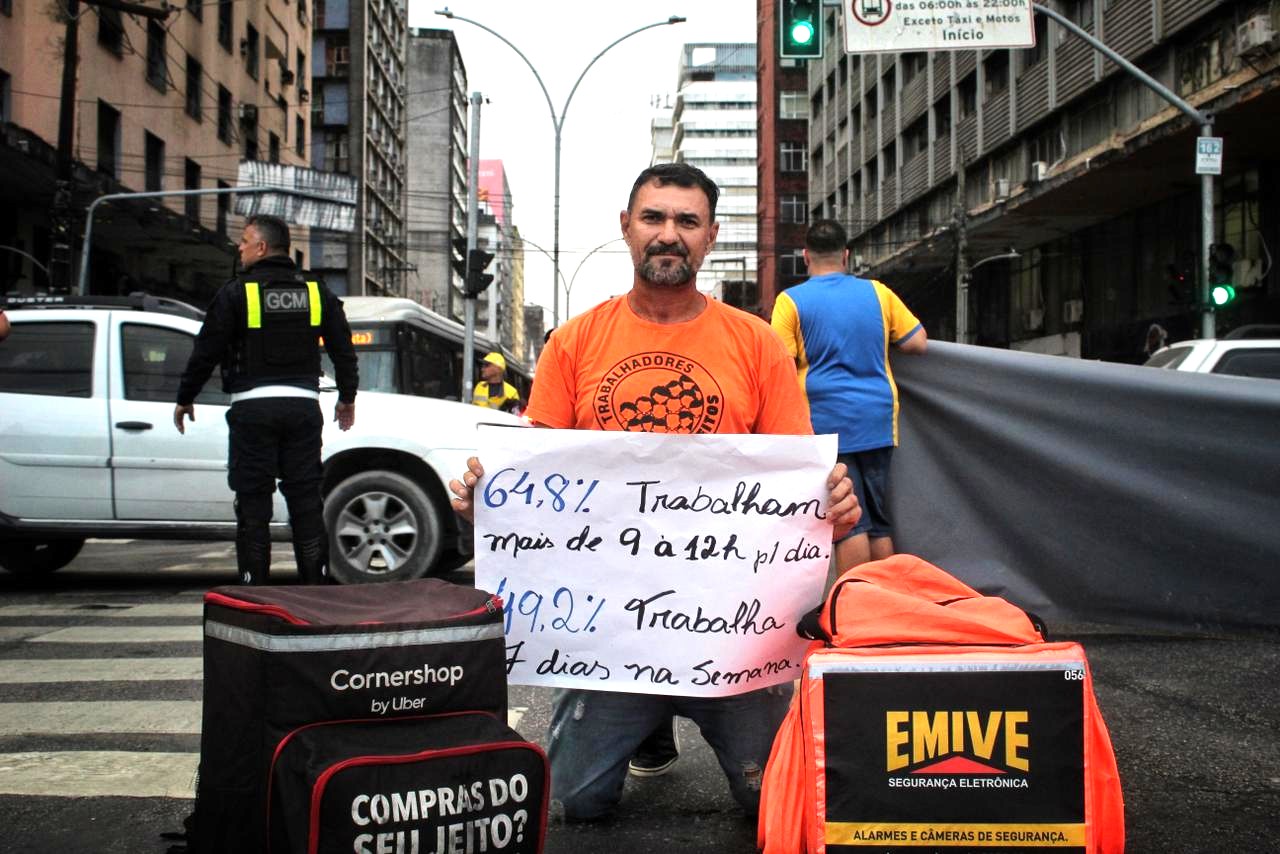

In Brazil, food delivery drivers have held strikes for better working conditions. Credit: Paloma Luna

Yet few such jobs provide wages that support these “platform workers,” who also have no job safety and are subject to unaccountable algorithms that determine kilometers (miles) and randomly lock out workers from their jobs.

“Pay is very low, not enough to meet our basic needs,” said the leader of the João Pessoa Municipal Delivery Workers’ Commission. “We are out on the street all day–12 to 15 hours–to make 100 reales (approximately $18), and even that is a struggle.”

Motorcycle and bike drivers are among Brazil’s 2.1 million app-based workers. In the two years since Solidarity Center’s ILAB-funded program began, digital platform workers have joined together, achieving a voice to advocate for passage of local legislation that combats violence against workers and creates worker support centers.

“The Solidarity Center is crucial to workers’ lives,” the delivery driver said.

Through Solidarity Center efforts at the national level, platform workers consulted with workers in their respective states, and then assisted lawmakers to introduce several amendments that include, for example, adding a right to worker compensation in case of accidents.

With Brazil’s first national negotiations in the digital platform sector ongoing this year, the abrupt funding termination has ended Solidarity Center’s efforts to assist workers to engage in shaping public and legislative debates on regulation.

And as platform workers’ participation in the negotiations has shrunk since funding termination, platform workers lack the means to hold accountable the multinational corporations that oppose regulations to enforce basic rights.

Across Nigeria, Bangladesh, Georgia, Brazil and beyond, workers describe the same story: hard-won progress lost, confidence eroded and exploitation unchecked. ILAB funding once ensured that women could report harassment, tea pickers could win a lunch break, miners could call inspectors, and delivery drivers could push for fair rules.

Now, those lifelines are gone.

Although the organization faces unprecedented threats, the Solidarity Center remains firmly resolved. The Solidarity Center for decades has stood with workers enduring difficult conditions in countries around the world—and will continue to do so. Because all workers deserve the right to form unions, to demand dignity, and to build a better future together.