When Enoch Gyaesayor logs into a digital app each day to begin picking up passengers and drive around Accra, Ghana, he hopes to get a few hour-long trips where he can be paid the daily top amount from Mondays to Fridays. After paying the company’s commission and job-related expenses, he says he makes 150 cedis ($14.64).

Enoch Gyaesayor, an app-based driver in Ghana, connected platform workers together in a union to build strength to improve working conditions.

But most of the time, Gyaesayor and thousands of other digital app drivers and riders are paid even less, and often work up to 16 hours a day, even sleeping in their vehicles to save petrol money going home and to be ready to start working again as quickly as possible. Higher pay on weekends does not reduce the amount of time they must work.

“There is no ‘off’ day for the driver,” Gyaesayor says, noting that he works seven days a week to support himself and his family.

In Ghana and in countries around the world, the Solidarity Center is building strength with platform workers to create a broad-based, global movement in which app-based workers join together to assert their rights, protect their lives and improve working conditions. Unions and worker organizations are making democracy real in workplaces, legislatures and global forums.

Digital Platform Work: A Growing Industry that Undercuts Labor Rights

A rapidly exploding industry, digital platform work now employs between 154 million and 435 million workers in online jobs. While often seen as a flexible job arrangement, digital app-based work is a growing business model that systematically undercuts labor rights and protections and shifts the responsibility of costs to workers.

With support by the Solidarity Center and the CGTP, digital platform drivers formed a union to collectively push for decent work and are now at the ILO in Geneva urging passage of a treaty improving work for platform workers worldwide.

Around the world, consumers depend on digital platform workers—requesting rides from Uber or Bolt, ordering meals from Zomato, receiving groceries delivered from Glovo, or viewing content on a social media platform. The online platform acts as an intermediary between the worker and the employer. For most workers, these jobs are not a “side gig”–they are full-time work.

Yet app-based workers in Ghana and in most countries worldwide are defined as “independent contractors,” and so not covered by national labor laws, such as a country’s minimum wage.

Some 3 billion consumers used online food delivery service—groceries and meals—in 2024. Although global food delivery alone was an estimated $380.43 billion in 2024, the workers transporting the food, driving passengers and moderating online content receive little pay and no safe and healthy working conditions.

Joining Together to Improve Job Conditions

Gyaesayor and other platform workers in Ghana say their top concern is to decrease the percentage of the commission app-based companies require drivers to pay. Uber takes 35 percent from workers’ pay; Bolt, 27.5 percent and Yango up to 25 percent.

The commission fee is only a portion of what workers must pay. With available cars scarce in Ghana, some companies “rent” cars to drivers, adding to a worker’s expense, which also includes mobile phone data, petrol and repairs.

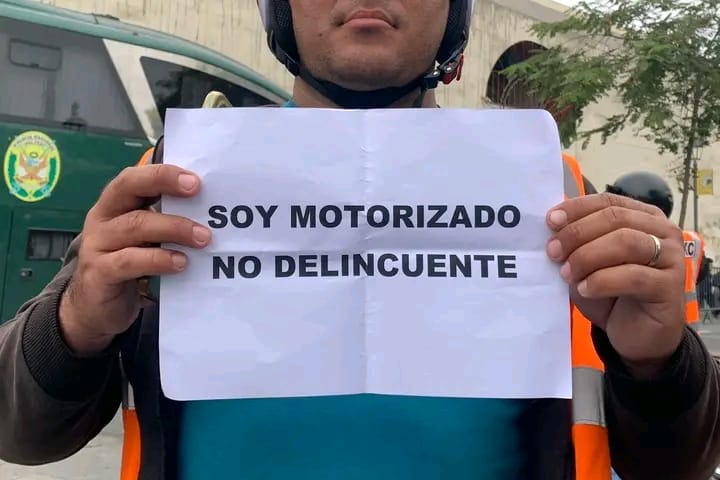

Delivery drivers say they suffer from exhausting workdays, low pay and poor health conditions. Credit: Paloma Luna

Algorithms, which often incorrectly determine distance, time and types of trips offered, further decrease pay. Workers operate at the will of the algorithm and have little recourse to find out why they are locked out of jobs or why kilometers are incorrectly calculated.

“There is a lot of uncertainty and lack of consistency when it comes to rides, how much you will get paid, and so on,” he says.

Gyaesayor, now general secretary of the Digital Transport Workers Union (DTWU), began joining together digital app workers by talking with platform drivers at car parks and shopping malls, urging them to come together to improve their conditions. Several associations representing couriers and other digital workers formed a small association in the Accra and Ashanti regions, By 2023, they created DTWU with a broader reach, joining the Ghana Trades Union Congress (GTUC).

Improve Working Conditions by Joining Together

The digital app union in Ghana, which includes car and bicycle drivers and couriers, is among dozens of platform worker unions around the world, with workers joining together to achieve key goals, including:

- Minimum wage standards.

- Safe working environments.

- Basic social protections such as annual leave, sick leave and retirement benefits.

- Labor law coverage in their countries grants them the same rights as all workers.

To gain these basic rights, workers are engaging in legal action to win unpaid wages, receive compensation for job-related injuries and establish safe working conditions. And, they are mobilizing to improve national and local laws.

Food delivery riders improved pay at FoodPanda in Cebu, Philippines, part of platform workers’ efforts to assert their rights, protect their lives and improve working conditions.

across the globe.

Earlier this year in Mexico, app-based workers campaigned for — and won! — legislative reform that recognizes them as workers and provides access to accident insurance, pensions, maternity leave and company profits. In the Philippines, food delivery riders are improving benefits around the islands. In Cebu, Foodpanda drivers will receive a base fare of 55 pesos (94 cents) and the company will recognize them as employees.

Now, the workers are joining together to take their demands internationally.

Platform Workers Take Global Action

This week, platform work will be formally addressed for the first time on a global stage. At an International Labor Organization (ILO) conference in Geneva, digital app workers and representatives from business and governments are shaping a new international treaty, Realizing Decent Worker in the Platform Economy.

At an ILO conference in Geneva, digital app workers and representatives from business and governments are shaping a new international treaty to ensure decent work for platform workers around the globe.

Digital app workers have been crafting content that delegates will consider, and joining meetings with the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and taking part in a six-day regional workshop in Togo by the ITUC-Africa. Platform workers also are involved in legislative strategies, meeting with their government representatives in advance of the conference.

Charith Attanapola, an app driver in Sri Lanka, met with the country’s minister of labor to convey platform workers’ challenges and discuss ways the government can improve working conditions.

“One of the key takeaways from our discussion was the government’s openness to ensuring decent work across all labor sectors, including app-based transport workers and delivery personnel,” says Attanapola.

Attanapola is part of the Solidarity Center delegation, which includes workers from Brazil, Chile, Ghana, India, Kenya and Mexico. As these workers testify, negotiate and help shape international labor standards that reflect the reality of their work and their demands, they understand the urgency in ensuring how jobs are shaped will determine the future.

In Ghana, where youth unemployment improved from 16.3 percent in 2000 to 5.4 percent in 2024, Gyaesayor knows that gain can be sustained only if decent work is available.

“Platform work has given employment to the majority of the youth; yet those of us who are working are being used like slaves, we get paid barely any salary,” says Gyaesayor. “The government must listen to the union, or things will get much worse; a lot of youth are going to be unemployed.”