Nov 19, 2015

“You have forgotten the Tazreen fire incident but our actual suffering has just started,” says Anju, who experienced severe head, eye and other bodily injuries during the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. fire in Bangladesh that killed 112 garment workers.

Survivors of the November 24, 2012, Tazreen fire who recently talked with Solidarity Center staff in Bangladesh say they endure daily physical and emotional pain and in many cases, have little or no means of financial support because they cannot work. Some, like Anju, who is unable to work, have never received compensation for their injuries.

Bangladesh’s $25 billion garment industry fuels the country’s economy, with ready-made garments accounting for nearly four-fifths of exports. Yet many of the country’s 4 million garment workers, most of whom are women, still work in dangerous, often deadly conditions. Since the Tazreen fire, some 34 garment workers have died and 985 have been injured in 91 fire incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital.

Some 80 percent of export-oriented ready made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh need improvement in fire and electrical safety standards, despite a government finding most were safe, according to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

The Solidarity Center has had an on-the-ground presence in Bangladesh for more than a decade. Through Solidarity Center fire safety trainings for union leaders and workers, garment workers learn to identify and correct problems at their worksites. But fewer than 3 percent of the 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh have a union. ” Despite workers’ efforts to form unions, in 2015 alone the Bangladeshi government has rejected more than 50 registration applications—many for unfair or arbitrary reasons—while only 61 have been successful. The rejections have jumped significantly from 2014, when 273 unions applied and 66 were rejected.

So that the world does not forget, here is the story of Anju and others who survived the Tazreen fire.

Photos: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

[portfolio_slideshow id=6745]

Apr 21, 2015

In the initial months after the Rana Plaza collapse on April 24, 2013, a preventable catastrophe that killed more than 1,130 Bangladesh garment workers and injured thousands more, global outrage spurred much-needed changes.

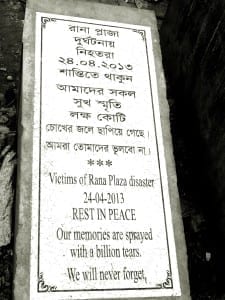

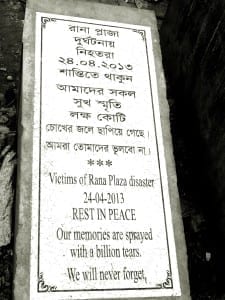

The site of the Rana Plaza building two years after it collapsed. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Dozens of garment factories were closed for safety violations through the Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord process, a legally binding agreement in which nearly 200 corporate clothing brands pay for garment factory inspections. Other inspected factories where problems were identified have addressed pressing safety issues. Workers organized and formed unions to address safety problems and low wages—and the government accepted union registrations with increasing frequency—after the United States suspended its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreement with Bangladesh based upon chronic and severe labor rights violations.

But in recent months, those freedoms are increasingly rare, say garment workers and union leaders.

“After the Rana Plaza and Tazreen disasters, it had become easier to form unions,” says Aleya Akter, president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF). But since November 2014, the government is more frequently rejecting registrations, she said, speaking through a translator while at the Solidarity Center in Washington, D.C., this week. The Tazreen Fashions factory fire five months before the Rana Plaza collapse killed 112 garment workers. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Overall government rejections of unions that applied for registration increased from 19 percent in 2013 to 56 percent so far in 2015, according to data compiled by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital. Despite garment workers’ desire to join a union, they increasingly face barriers to do so, including employer intimidation, threatened or actual physical violence, loss of jobs and government-imposed barriers to registration. Regulators also seem unwilling to penalize employers for unfair labor practices.

“In our view, a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry,” according to a March International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) report. “The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.”

Meanwhile, thousands of workers still toil in unsafe factories. In the two years since the Tazreen fire, at least 31 workers have died in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh, and more than 900 people have been injured (excluding Rana Plaza), according to Solidarity Center data. The Accord and the non-legally binding Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety have nearly completed their inspections, which will total fewer than half of the country’s 5,000 garment factories, including 600 factories that have refused entry to inspectors, according to the International Labor Organization.

In recent months, the Solidarity Center has conducted a series of fire safety trainings for garment workers near Dhaka and Chittagong, where most garment factories are located. The 10-day trainings provide workers with hands-on fire and building safety experience.

Following one recent training, Lima, a factory-level union leader, says she “learned a lot.

“We organized our union in mid–2014. The staircase that workers use in my factory used to be blocked and was a fire hazard. But through our union we took the initiative to talk to management about the problem and now the staircase is clear.”

When garment workers like Lima are allowed to form unions, they have the opportunity to create positive changes at their workplaces, making unions fundamental to substantive improvements in Bangladesh garment factories—an opportunity fewer and fewer garment workers can grasp in the current environment.

Dec 10, 2014

Each year on December 10, the global community marks International Human Rights Day, anchored in the founding document of the United Nations which asserts that each one of us, everywhere, at all times is entitled to the full range of human rights.

That founding document, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, also lists “the right to form and to join trade unions” as a basic tenet of human freedom. For many workers around the world, the right to form unions is essential for ensuring the safe working conditions and living wages that are fundamental to human rights.

Two years ago, on November 24, the devastating fire at the Tazreen Fashion Ltd. garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killed 118 workers, the majority of them young women. Commentators at the time compared the disaster to the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York, noting that moment in American labor history when young women garment workers began organizing their first unions.

The same phenomenon is taking root in Bangladesh, and for the same reasons. The momentum for union formation was accelerated by the April 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh, which killed more than 1,100 workers. Following these twin tragedies, workers, primarily women, formed more than 200 new garment unions. Their rapid formation has been driven by the determination of women workers who have experienced how the past 30 years of job creation has not led to their economic or social advancement. They seized the moment to collectively join together to demand that jobs offer more than a meager paycheck.

It has been a nostrum of development economics for the past 20-plus years that merely creating garment-sector jobs was the key to women’s liberation and empowerment. True, approximately 80 percent of workers employed in the Bangladesh’s garment sector are women. True, millions of women now have an independent means of earning an income, which is important to raising women’s status within their family and community.

However, few adherents to this economic analysis have examined whether creating low-wage jobs has truly led to women’s empowerment in a way that is personal, cultural, sustaining or lasting. Rather, many economists and political scientists view Bangladesh and the global garment supply chain through a purely free-market perspective. Through this lens, any wages at all enable women to improve their status. Yet it is much more difficult to acknowledge that the real issue is the global supply chain within which women need to exert their power and genuinely take control of their own destinies inside and outside the home.

Statistical evidence suggests that women toiling at the bottom of the global garment supply chain in Bangladesh do, in fact, experience some social changes in contrast to women working in a subsistence agrarian economy. Research shows that a 10-hour-a-day, six-days-a-week job in the Bangladesh garment industry may improve women workers’ chances to send their children to school and keep them in there longer. However, these arguments are oversold. Women garment workers may or may not control their wages, depending upon gender-based power relations inside their homes. Often, they do not favor women.

Over the past 17 years that I have been involved with the Bangladesh labor movement, I have repeatedly seen how an income does not guarantee independence for a woman garment worker. This anecdotal evidence is backed up by fact. Research suggests that girls age 17 and 18 years old who live near garment factories actually drop out of school at a higher rate than their rural counterparts who go to work in the industry. Further, a 2009 study by the Bangladesh government’s National Bureau of Economic Research documents that non-garment workers’ mothers had a higher level of education than those of garment workers. And farm labor actually pays more than a job at a garment factory in the high-cost, high-inflation environments of Dhaka or Chittagong, according to a recent article in Dhaka’s Financial Express.

So if the one-dimensional argument that earning a wage results in women’s empowerment is fiction, what is the manifestation of real progress for women?

For the answer, I would point to prominent labor activists who have risen from the factory floors and now are organizing among their peers.

Kalpona Akter, Nazma Akter (no relation) and Nomita Nath, for example, all worked as child laborers in garment factories. They have emerged as real leaders, not because they made poverty wages as teens but because they dedicated their lives to uplifting the status of women workers in their society. They have found their power in fighting for jobs that do not starve, maim or kill women. And they know that vulnerable workers find empowerment when they have a union to represent them.

Workers struggle every day on Bangladesh’s factory floors. Women report that physical and verbal abuse are a matter of course. They are threatened when they do not make a quota or when they get pregnant. Or worse. Mira Boashak, president of a local union in Dhaka, was severely beaten in August by several men who had staked out her garment factory.

Despite these challenges, a young organizer told me earlier this year in Dhaka that prior to recent tragedies, her efforts to organize women into unions made her community think she was a troublemaker. Now, she said, she is seen as a champion of women’s rights and looked up to as a leader.

Real women’s empowerment—realized through asserting fundamental human rights.

Nov 21, 2014

November 24 marks the two-year anniversary of the deadly fire at Tazreen Fashions Ltd. in Bangladesh that killed 112 garment workers. Since then, at least 30 garment workers have died in factory fires and 844 have been injured in 68 incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital. Many of the survivors and their families say they have received little or no compensation, and many survivors are unable to work again.

“Things are getting much, much worse for me,” said Shahanaz, who sustained critical injuries, including loss of vision in her right eye, while fleeing the burning building. “With all of the pain I am in, I can no longer pray while standing.”

Shahanaz is one of nearly a dozen garment workers and family members the Solidarity Center profiled last year. Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka recently visited the workers again, and found that, like Shahanaz, their health and financial situations have deteriorated.

Five months after the Tazreen fire, another 1,100 garment workers in five factories were killed and another 2,500 people were injured when the Rana Plaza building collapsed.

Millions of garment workers, up to 90 percent of whom are women, have made Bangladesh the second largest producer of apparel globally, and 80 percent of the country’s foreign exchange depends upon the industry. Garment workers have toiled for decades in hazardous working conditions with few worker rights. After the Tazreen and Rana Plaza disasters shocked the world, these worker rights violations could no longer be ignored.

Following the Rana Plaza collapse, the United States suspended its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreement with Bangladesh based upon chronic and severe labor rights violations. In the weeks after the suspension, the Bangladeshi government dropped charges against two prominent garment union leaders. It has since registered more than 200 unions representing more than 50,000 workers. By contrast, only two garment unions were registered between 2010 and 2012.

Yet some 25 percent of new unions are in factories that have closed or are inactive due to anti-union activities, according to Solidarity Center data. Further, in at least 46 factories with unions, workers have faced severe anti-union violence, mass terminations and/or threats.

International retailers have joined together in two separate groups to improve safety at factories where they contract work. More than 175 international retailers signed on to the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, a legally binding agreement negotiated with the global unions, IndustriALL and UNI. Another 26 primarily U.S. and Canadian companies signed the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, which is not legally binding. After inspecting some 1,700 of Bangladesh’s 5,000 garment factories, the Accord and the Alliance identified 33 factories in which safety issues are so serious that they recommended production be suspended because of the risk to workers.

However, questions remain about who will pay for the cost of repairs and who inspects the remaining factories that neither the Accord nor Alliance says are their responsibility. The Accord and Alliance claim 1,800 factories are under their purview, but a recent study estimated the total number is between 5,000 and 6,000 factories and facilities.

The Solidarity Center has had an on-the-ground presence in Bangladesh for more than a decade. This year, following Solidarity Center fire safety trainings, garment workers have used their new skills to identify and correct problems at their worksites. Joni and Rabeya, president and general secretary of B. Brothers Garments Co. Ltd. Workers Union, found 15 expired fire extinguishers and located electrical hazards in their factory, such as faulty electrical wiring. They raised these fire safety issues with management, which has since corrected some of the issues.

Recognizing that workers who freely form unions can better advocate for job safety and decent wages, the Solidarity Center believes there is need for:

• A clear and transparent trade union registration process.

• Quick resolution of unfair labor practices by the Bangladesh Labor Department, with penalties for employers who engage in them.

• Development of an independent alternative dispute resolution mechanism in the face of inefficient labor courts

Feb 18, 2014

Garment workers and workers in other industries in Bangladesh’s export-processing zones are subject to a different, much weaker set of labor laws than workers in the rest of the country, and the government must take steps to reform laws so they meet international standards for freedom of association and collective bargaining rights, said A. K. M. Nasim, senior legal counselor at the Solidarity Center’s office in Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital. Further, “if we have any half-hearted reform in the legislation, it will mean that the workers will have to continue their struggle for a period of at least a generation to achieve these fundamental rights.”

Speaking at a recent forum in Washington, D.C., Nasim gave an overview of the current labor rights environment for Bangladeshis and provided key recommendations for improving their wages and working conditions.

Some 377,600 workers, the vast majority women, work in eight export-processing zones (EPZs) throughout the country.

Bangladesh derives 20 percent of its income from exports created in the EPZs, which are industrial areas that offer special incentives to foreign investors like low taxes, lax environmental regulations and low labor costs.

Yet while workers outside the EPZs are permitted to form trade unions, EPZ workers must form weaker workers’ welfare associations. Even though the associations have the right to bargain and negotiate agreements with employers, in practice, employers do not let the workers form their associations easily. Leaders of workers’ associations who actively promote the interests of the employees “have been fired from their jobs,” Nasim said. “As a result, most of the workers’ associations in the EPZs remain in existence only on paper.”

Nasim discussed the decision last June by the U.S. government to suspend Bangladesh’s trade benefits based on the country’s chronic and severe labor rights violations. The United States suspended its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreement with Bangladesh after 112 workers were killed in a 2012 fire at the Tazreen garment factory, and more than 1,100 died last April when the Rana Plaza building collapsed. Since the GSP suspension, the Bangladesh government has allowed some 100 unions to register, in contrast with the few unions recognized prior to last year.

The Rana Plaza disaster also led to the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, a five-year binding agreement between international labor organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and retailers in the textile industry to maintain minimum safety standards. The tragedies also have generated an increase in NGO involvement, and Nasim urged the NGOs working to improve workplace safety and health to support workers in forming and running unions, and making sure they are sustainable in the long run.

Also speaking at the forum, Solidarity Center Asia Regional Director Tim Ryan showed how the economic and political intersect in the Bangladesh context as described by Nasim.

“Bangladesh is a crucible for the intersection of globalization, the government’s economic policies, how these impact on the development of a democratic culture in civil society, and equitable and just economic growth that benefits workers and their families,” Ryan said. “A voice for workers in this process is absolutely crucial for growing democracy and democratic organizations in Bangladesh.”

The forum, “Strengthening Democratic Practices in Bangladesh: Empowering Workers in Export Processing Zones,” was sponsored by the National Endowment for Democracy and included Zerxes Spencer from the International Forum for Democratic Studies as moderator.