Annual Report, 2018–2019

Download here.

Download here.

[ Read Article ]

Imagine the population of New York City. Then triple that number. That’s how many people around the world are being robbed of their freedom through human trafficking—24.9 million.

While “trafficking” seems to imply movement across borders, some 77 percent of those targeted by human traffickers do not leave their country of residence, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). Most are trafficked for forced labor, one-third are children.

Solidarity Center’s Neha Misra testified on Capital Hill on the need for worker rights in forming unions and bargaining as key to ending human trafficking. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“Human trafficking thrives in a context of private actors and economic coercion,” says Neha Misra, testifying recently on Capitol Hill before the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission in a House Foreign Relations Committee hearing.

“We must address what one leading global expert on the international law of human trafficking calls the ‘underlying structures that perpetuate and reward exploitation, including a global economy that relies heavily on exploitation of poor people’s labor to maintain growth and a global migration system that entrenches vulnerability and contributes directly to trafficking,’ ” says Misra, Solidarity Center senior specialist for migration and human trafficking. Trafficking and severe labor exploitation are part of a continuum of labor exploitation and abusive working conditions workers face around the world in workplaces as diverse as factories, farms and offices.

The Lantos hearing was part of a series of congressional events in January around U.S. Human Trafficking Awareness Month, which marks the date Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) in 2000. That same year, the United Nations passed the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (the Palermo Protocol). As part of the TVPA, the U.S. State Department each year issues a detailed report on trafficking in persons, ranking countries on the extent to which they are addressing and eliminating it.

Since then, global nations have a clearer understanding of human trafficking—including its direct connection to forced labor and exploitation—and 168 governments have implemented domestic legislation criminalizing all forms of human trafficking, transnationally and nationally.

Yet as indicated by the staggering number of those trafficked, much more needs to be done.

“Over the past 20 years, the extent of forced labor in global supply chains has become increasingly clear. And yet, governments continue to fail to hold corporations to account,” says Misra.

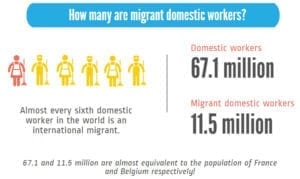

Isolated in private homes, domestic workers, whether nationals or migrants, are particularly at risk of exploitation, harassment and abuse, including sexual violence—and have difficulty accessing justice. Domestic workers, who comprise 11.5 million migrant workers—are also among the largest group of trafficked migrant workers and are vulnerable to human trafficking and forced labor—within their home countries, as internal migrants, and as cross-border migrants.

Isolated in private homes, domestic workers, whether nationals or migrants, are particularly at risk of exploitation, harassment and abuse, including sexual violence—and have difficulty accessing justice. Domestic workers, who comprise 11.5 million migrant workers—are also among the largest group of trafficked migrant workers and are vulnerable to human trafficking and forced labor—within their home countries, as internal migrants, and as cross-border migrants.

“Recognizing domestic workers as workers is key to combatting the vulnerability they face to human trafficking,” says Alexis De Simone, Solidarity Center senior program officer for the Americas. De Simone spoke at a Capitol Hill briefing Friday sponsored by U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal.

A domestic worker who requested anonymity described at the briefing the abusive conditions she experienced after a diplomat brought her from Chile to the United States in 2009. She was promised fair wages and benefits, but after she started working, the family refused to pay her. Her employers withheld food, stole her passport, and threatened her with deportation if she talked with anyone outside the household—an all-too common experience for domestic workers worldwide.

Combating human trafficking, forced labor and other forms of severe labor exploitation means putting worker rights at the forefront of solutions.

The 2011 ILO convention (global treaty) covering domestic workers “has raised the bar globally for states and employers to recognize and enforce the labor rights of domestic workers,” says De Simone.

Domestic workers around the world educated and mobilized for passage of the ILO Convention on Domestic Workers, along the way helping workers understand that violence, abuse, coercion and intimidation are not part of the job. “And that recognition, that righteous indignation, is often the spark for organizing that helps us end the imbalance of power,” says De Simone.

“Recognizing domestic workers as workers is key to combatting the vulnerability they face to human trafficking”—Alexis De Simone, Solidarity Center. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

Yet not only international law, but on-the-ground grassroots union organizing and building power among domestic workers is key to combating vulnerability to trafficking, she says. “Union contracts are helping domestic workers worldwide ensure their rights to safe jobs without forced labor and human trafficking.”

De Simone cited examples of how union collective bargaining agreements have improved conditions for domestic workers in Argentina, Uruguay and Sao Paulo, Brazil, and shared the success of domestic workers in Mexico who ensured the country’s new labor law includes domestic workers—often among an excluded group of workers in many country’s labor laws.

Unions also are reaching across borders, building union-to-union relationships between countries of origin and destination like Paraguay and Argentina, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, Nepal and Lebanon.

But “freedom of association must be assured in practice, not just law,” says Misra. “This means strict penalties for employers who fire, retaliate against or collude with government officials to deport migrant workers seeking to form unions.”

Says Misra: “From rubber plantations in Liberia, garment factories in Jordan and to domestic workers’ households in Kenya, Solidarity Center has seen time and again how democratic worker organizing and collective bargaining can eliminate forced labor in a workplace.”

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and the Network Against Anti-Union Violence in Honduras are urging the government to drop all charges against Moisés Sánchez, safeguard his protection as a human rights defender under threat, and ensure he can freely exercise his union activities without violence or reprisal.

Sánchez, secretary general of the melon export branch of the Honduran agricultural workers’ union, Sindicato de Trabajadores de la Agroindustria y Similares (STAS), is on trial January 22 for criminal charges without the right to appeal. He is charged with four counts related to “usurpation” for his community’s construction of an access road and faces a possible 30-year prison sentence.

In the southern community of La Permuta, 450 community members voted in 2018 to build a road allowing residents regular access to nearby towns after government officials documented that the land was publicly owned. Previously, La Permuta residents were unable to cross rivers during heavy rains to Choluteca, where many work in the melon fields.

More than a year after the road was built, a land owner claimed the land as her property and pressed criminal charges. Five elected community leaders have been charged. Sánchez is the only grassroots community member not part of the elected leadership who was charged for the road construction. The Network believes Sánchez is being targeted for his role in seeking decent wages and working conditions for agricultural workers, moves often violently opposed by their multinational employers. The Network fears he would face violence and possible death if imprisoned.

In 2017, Sánchez and his brother, union member Misael Sánchez, were attacked by six men wielding machetes as they left the union office in Choluteca. The company later fired him in what union leaders say is retaliation for his efforts to improve working conditions through a union. Sánchez is among those listed by the International Labor Organization (ILO) as requiring protection from the Honduran government, and as a documented victim of anti-union violence, the Network says that the state has an obligation to protect human rights defenders and should not permit these attacks on their lives and liberty.

The Network’s most recent report on union violence, released in August, finds agricultural worker activists represented three quarters of the victims of anti-union violence in Honduras between February 2018 and February 2019. Yet according to the Network, no arrests were made in 60 cases of anti-union violence in the past three years.

Melon workers on plantations across the Choluteca region have long endured worker rights abuses. After they sought to improve their working conditions by forming unions in 2016 with STAS, a FESTAGRO affiliate, employers intimidated and illegally fired many workers, despite Honduran law and international conventions making it illegal to retaliate against workers for organizing unions to protect their rights on the job.

The ILO held back-to-back hearings at the International Labor Conferences (ILC) in 2018 and 2019 on Honduras’s failure to abide by its international commitments. The ILC report in 2018, which expressed “deep concern at the large number of anti-union crimes, including many murders and death threats, committed since 2010,” urged the Honduran government to protect vulnerable unionists, investigate more than a decade of unsolved murders of union leaders and prosecute those responsible for the crimes.

In 2012, the AFL-CIO and 26 Honduran unions and civil society organizations filed a complaint under the labor chapter of Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). The complaint, filed with the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Trade and Labor Affairs, alleges the Honduran government failed to enforce worker rights under its labor laws. In an October 2018 report, the U.S. Trade and Labor Affairs office said Honduras had made no progress on any of the emblematic cases since 2012.

Thousands of casino workers at NagaWorld hotel and casino complex in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, won a wage increase that boosts pay between 18 percent and 30 percent and secured the reinstatement of union president Sithar Chhim, who was suspended from her job in September for defending the right of a union member to wear a shirt with a message that called for higher wages. The agreement also provides a $200 incentive for workers without health insurance and a bonus equal to roughly two months’ salary, says Chhim.

Credit: Solidarity Center

Some 5,000 of the 8,000 workers—including dealers, slot machine workers, housekeepers and technicians—struck the casino January 9, and more than 4,000 rallied outside the complex for two days with signs saying “Demanding living wages is a right, not a crime!” and holding placards with photos of Chhim seeking her reinstatement. Chhim, a game floor supervisor, is branch president for the Khmer Employees’ Labor Rights Support Union of NagaWorld.

NagaCorp, a five-hotel resort and casino, has an exclusive, multidecade license to operate in Phnom Penh and reported an estimated $1.8 billion in revenue last year, up from $1.5 billion in 2018. Yet housekeepers are paid $191 per month.

Police at NagaWorld hotel and casino as workers rallied outside. Credit: Solidarity Center

In May, nearly all 4,000 union members signed a petition demanding a wage increase, and the union began negotiations with the employer in June. When the company did not return to the bargaining table after three months as it indicated it would, more than 1,500 union members met September 19 and agreed to wear T-shirts with a message highlighting the company’s profits and expressing workers’ need for a wage that pays their rent, food, transportation and other basic monthly expenses.

The next day, Chhim was detained for hours at the facility and suspended. Union members immediately walked out in support of her. Sithar told Equal Times she then urged her colleagues to continue to work as usual, while organizing subtle protest actions, which included union members wearing pink face masks, black armbands and other markers of solidarity as they enter and exit the tightly guarded checkpoints of the complex.

After the union provided legal notice of the strike, the company continued hiring new workers, providing them accommodation and food in the company’s building and prohibiting them from leaving the facilities or contacting their families, according to the union.

The casino workers’ victory is all the more notable because of the many recent challenges to worker wrights in Cambodia.

Union leaders say amendments to 10 articles in Cambodia’s Law on Trade Unions restrict fundamental union activities. For instance, one amendment deprives unions of their right to hold legal strikes. “[Holding] a legal strike is always difficult, and I think the barriers in the Trade Union Law have actually made it more difficult,” says William Conklin, Solidarity Center Cambodia country director.

Cambodia’s labor rights are currently under intense scrutiny, as the European Union decides whether to rescind the nation’s preferential trade status that grants Cambodian exports duty-free access into EU markets.