Aug 9, 2018

Marie Constant has worked as a domestic worker in Lebanon since 1997. Originally from Madagascar, Constant has been fortunate to have a good employer. But most migrant domestic workers are not so lucky.

“In general, domestic workers [must] work from morning until evening with no specific break time and no holidays,” she says, speaking in French through a translator. “When we receive guests, we don’t have choice but to stay up late working until the guests leave, which is usually around midnight or sometimes around 1 a.m. Most domestic workers don’t have the right for the weekly leave.”

“And because of these rights abuse, we decided to form a union to defend our rights.”

(Constant discusses domestic workers and the struggle for rights on the job in this Workers Equality Forum video.)

‘We Are Advancing”

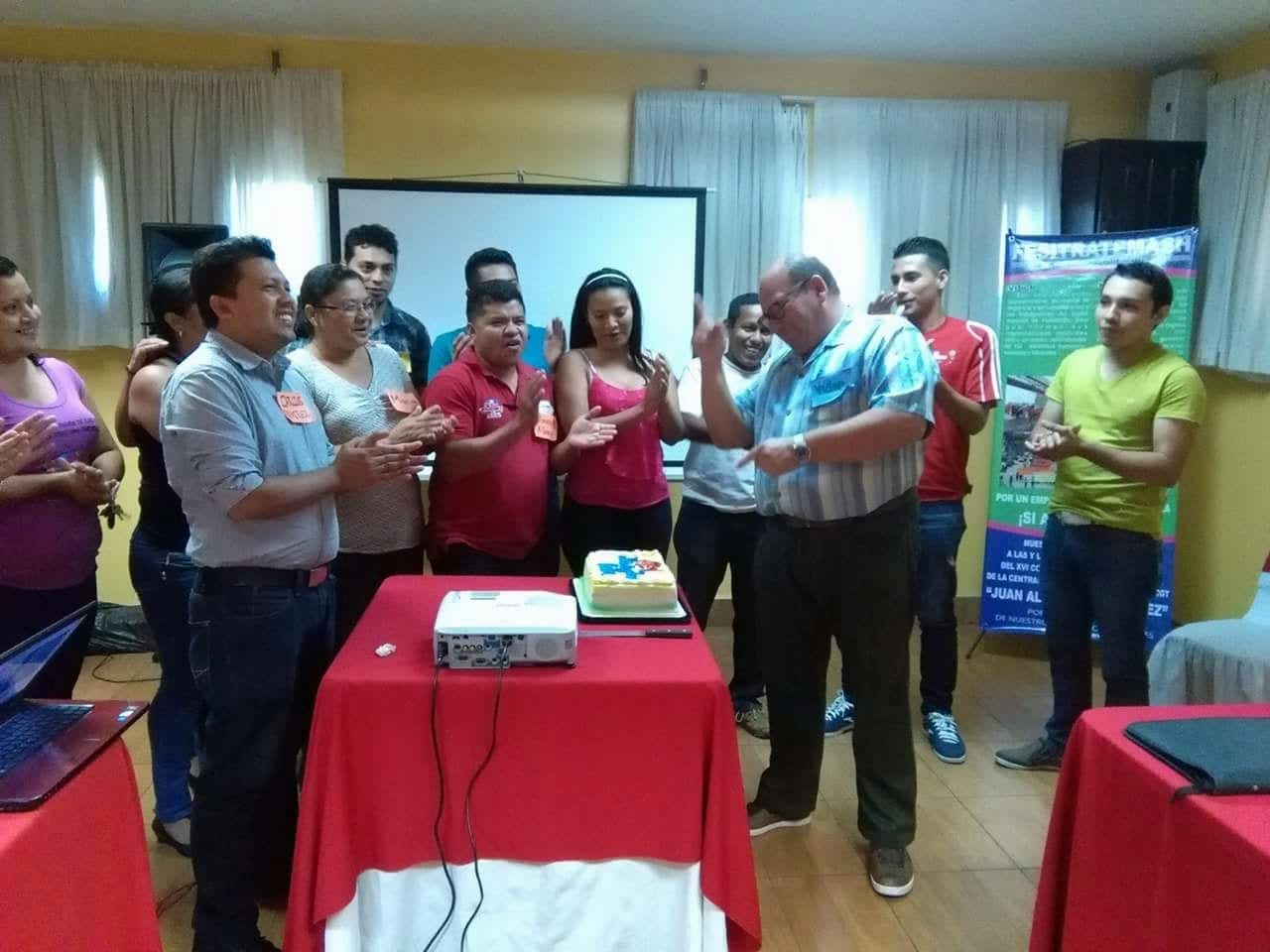

Marie Constant (center), joined other domestic worker rights advocates in Morocco last year for a Solidarity Center forum on decent work. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

In 2015, she joined 300 domestic workers at the founding congress of the Domestic Workers Union in Lebanon, the first union of migrant domestic workers in the Arab region.

The union “is a source of great pride for us,” Constant says. Affiliated to the National Federation of Workers’ and Employees’ Unions in Lebanon (FENASOL), the union is yet to be officially recognized by Lebanon.

Much of Constant’s outreach involves informing domestic workers about the options for improving their wages and working conditions.

“We try to reach out to all the domestic workers women in most the regions in order to educate them about their rights.”

Despite the challenges, Constant recognizes domestic workers in Lebanon have taken big steps toward achieving dignity and decency on the job to which they and all workers are entitled, and she is optimistic about the future.

“We have a lot of hope. Even if we know we have a long way to go and that there are a lot of hurdles along the way, we are advancing, not regressing.”

Jul 19, 2018

The Solidarity Center is mourning the loss of Victor Hugo Quesada Arce, Solidarity Center project coordinator in Costa Rica, who died July 16 after a battle with cancer.

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”

In his 30 years of strengthening unions and educating workers about their rights, Victor worked side by side with some of the most vulnerable and marginalized workers in the region. He helped revitalize plantation worker unions which primarily represent migrant workers in Costa Rica and which had been decimated by decades of anti-union assaults.

Victor came to the Solidarity Center five years ago as a worker rights advocate well-known across the region, and agriculture unions from throughout Central America have been sending tributes and an outpouring of appreciation for his many years of solidarity and support.

“We stand in solidarity and send hugs to friends, relatives of our brother Victor,” writes FESTAGRO, the agriculture union in Honduras. “People like you are one of a kind, and are always remembered.”

Jul 18, 2018

Worker rights advocates are hailing a recent court decision in Thailand that dismissed criminal defamation charges against 14 migrant workers from Myanmar who faced jail time after reporting abusive working conditions on a poultry farm.

Fourteen workers who left the farm in 2016 described forced overtime, unlawful salary deductions, confiscation of passports and restrictions on freedom of movement in a complaint to the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand.

In retaliation against the workers for submitting the complaint, the Thammakaset Co. Ltd. filed a criminal defamation complaint against the 14 workers, alleging they falsified claims to damage its business interests.

The case put a spotlight on abuse in the supply chain, says Solidarity Center Asia Regional Director Tim Ryan. The ruling “strikes a blow against the criminalization of promoting labor rights,” and is a landmark for migrant worker rights and freedom of expression.

“Companies filing criminal defamation complaints against workers who seek justice on the job is an all-too common practice, one often used as justification for dismissal. This decision is in line with international legal standards supporting free speech, freedom of assembly and other activities key to an open civil society.”

Workers Increasingly Migrate for Jobs

One of the migrant workers says he worked 22-hour shifts for more than four years at the Thammakaset 2 Poultry farm, which supplies one of Thailand’s largest chicken export companies. Myint told the Guardian that each day, he would kill up to 500 birds for food processing. At night, he and his co-workers say they slept on the floor in a room with up to 28,000 chickens, swatting away insects. If a bird got sick, they were to blame.

Of the 232 million migrants around the world, 150 million are migrant workers. Millions of migrant workers like Myint and his co-workers are unable to find family-supporting jobs in their origin countries. With labor migration increasing as men and women seek to support their families, the case highlights the rights of migrant workers seeking justice for workplace abuse.

A team of United Nations human rights experts this year called on Thailand to “end recurring attacks, harassment and intimidation of human rights defenders, union leaders and community representatives who speak out against business-related human rights abuse.”

Referring to the Thammakaset case, they said “business enterprises have a responsibility to avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts; therefore it is a worrying trend to see businesses file cases against human rights defenders for engaging in legitimate activities.”

Thammakaset also filed a criminal complaint against two of the 14 workers and a Migrant Worker Rights Network coordinator for the alleged “theft” of time cards, taken by the workers to show labor officials evidence of their claims about a 20-hour working day. MWRN, a Solidarity Center partner, is a membership-based organization for migrant workers from Myanmar working in Thailand.

Feb 16, 2018

Migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong, Special Administrative Region of China, must live with their employers, according to a court ruling this week that rejected a case by a Philippine migrant worker who argued the rule violates Hong Kong SAR’s Bill of Rights and other basic laws.

Credit: Sally Choi

Expressing disappointment in the court’s decision, the Federation of Asian Domestic Workers Unions (FADWU) vowed to continue to demand that “the government revise regulations that prohibit living (outside the employer’s home) and develop concrete policies to ensure that migrant domestic workers who live with their employers enjoy reasonable living conditions.”

Among the 400,000 domestic workers in Hong Kong, SAR 335,500 are migrant domestic workers. Isolated in homes, they often are subject to physical and verbal abuse and subjected to overwork and poor living conditions. Some 52 million domestic workers are employed in countries where they are completely excluded from national labor laws.

Although Hong Kong, SAR laws cover the working conditions of domestic workers, FADWU urged the government to enforce the laws.

“The government should also take the responsibility to ensure enforcement and to conduct inspections to ensure that migrant domestic workers’ rights to privacy, self-improvement, rest time and private life are protected, and also to ensure that migrant domestic workers have safe working environments, equality and dignity,” the union says in a statement.

On Sunday, hundreds of migrant domestic workers rallied at Hong Kong SAR’s City Hall to demand an end to violence against women, and called on the government to reform regulations covering migrant workers to ensure they work regular hours, receive decent food and sleeping quarters.

Jan 31, 2018

After spending seven years in Jordan as a domestic worker, Suryanti sought to return home to Indonesia to see her family. But her original employer, whom she left under duress, had confiscated her passport and would not give it back, leaving Suryanti in legal limbo as she tried to leave the country.

Securing a new passport required months of court filings and, ultimately, four-and-a-half-months in a detention center in Amman before Suryanti was allowed to leave the country. While confined, officials took her mobile phone, and she had no means to initiate communication with anyone.

In fact, some migrant workers who are jailed for not paying visa overstay fines in Jordan end up in detention for years. A survey found some 55 percent of migrant workers in detention were held between three weeks and four months, 18 percent for five to 11 months, and 5 percent for between one and two years.

“I didn’t know how long I would be there,” Suryanti says, describing her months in detention. “I was frightened.”

Jordan Domestic Workers Network

Now back in Indonesia, Suryanti plans to assist migrant domestic workers know their rights. Credit: Suryanti

With few legal rights in Jordan, domestic workers like Suryanti, 32, have been trying to improve the lives of migrant domestic workers with education, awareness training and legal aid through the Jordan Domestic Workers Network. Some 400 domestic workers have benefited from the network’s services, including 180 members from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Philippines and Sri Lanka. Suryanti, one of the founding members, says she has helped some 200 Indonesian migrant domestic workers take part in network activities, a task she undertook “because we have the same problems.”

Formed in 2014, the network is the first organization to bring together migrant domestic workers in the region, where countries typically prohibit migrant workers from forming or joining formal trade unions and negotiating with employers to improve wages and working conditions. Through the network’s partnership with the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF), migrant workers also are connected with IDWF affiliates in some countries of origin. A key draw for domestic workers is the legal clinic with the Adalah Center for Human Rights Studies.

Jordan and other Middle Eastern countries operate under a kafala system, in which worker visas are tied to a particular employer, essentially inhibiting workers from reporting abuse and denying them the ability to change jobs. Employment contracts can only be terminated if both parties agree, if the duration of the contract has expired, or if the worker dies or is no longer capable of working due to a disease or disability certified by a medical authority. In practice, this means workers seeking to leave abusive employers often cannot get their permission and so are forced to seek employment elsewhere, without their passports.

Further, employers are responsible for annually renewing the work and residency permits of their employees, yet migrant workers are required to pay fines—$64 per month, nearly half the monthly salary of many workers—when employers do not renew the permits and they expire.

“Almost always, the original employer keeps our passport,” Suryanti says, speaking from Jakarta, where she now lives. “I don’t know why the original employer didn’t give us our passport because a passport is our right.”

Migrant Domestic Workers Vulnerable to Abuse on the Job

Migrant domestic workers from Indonesia and elsewhere not only are at risk of having their passports confiscated by employers, but often endure overwork and physical abuse, isolated in their employers’ homes.

A first-ever nationwide survey of Indonesian migrant workers by the World Bank gives a glimpse into the working conditions of all migrant domestic workers in the Middle East. The 2017 survey found some 26 percent of Indonesian migrant domestic workers in the region endure long working hours, 52 percent do not receive any days off, and 88 percent are not paid for overtime work. Suryanti says she left her first employer’s house after three months because in addition to cleaning the house, she was forced to clean the houses of the employer’s mother and sister, and was never allowed to rest.

“They always make me work, work, work, but you know, I am a human,” she says.

Between 440,000 and 540,000 migrants work in Jordan, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). More than 9 million Indonesians work abroad—nearly 7 percent of Indonesia’s total labor force (only China and the Philippines send more workers abroad). Roughly 40 percent are domestic workers and caregivers, and each year this predominantly female migrant workforce contributes 51 percent of total remittances sent to Indonesia.

Migrant workers also are at risk when they connect with unscrupulous labor brokers who make false promises about wages and working conditions. Suryanti says a labor broker in Indonesia told she would get a job abroad working in an office for $250 a month. Instead, she was forced to toil as a domestic worker for $150 a month. “I didn’t know I would be domestic worker,” she says.

Suryanti ultimately worked for several employers, most of whom abused and overworked her, and often would not pay her.

Despite her struggles, Suryanti remained active in the network, assisting domestic workers whenever possible. She attended English classes to improve her mastery of the language to better assist other domestic workers, and joined a training on care giving with migrant domestic workers from the Philippines to improve her work skills.

Now working as a cook and translator for an employee of a Middle Eastern embassy in the Indonesian capital, Suryanti is connecting with migrant workers and the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union (SMBI), where she plans to continue her efforts ensuring those working in isolation have the power of solidarity.

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”