Jan 15, 2015

Some 45 labor groups and other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) sent a letter to the Thai prime minister yesterday protesting a proposed plan to use prison labor on fishing boats.

Saying the plan threatens the human rights of prisoners and likely goes against the International Labor Organization’s convention on forced labor, the letter states:

“The Thai government should recognize the only way to address the labor shortage on Thai fishing vessels is to make enforcement of labor laws on fishing boats a priority and improve conditions so that the sector can attract workers to voluntarily work on the boats.”

Thailand’s move comes despite worldwide attention on abuses in the Thai fishing industry. In June, the U.S. State Department downgraded Thailand in its annual Trafficking in Persons Report, which could subject Thailand to sanctions, among them the withholding or withdrawal of U.S. non-humanitarian and non-trade-related assistance.

In the letter, the organizations, which include the International Trade Union Confederation and the AFL-CIO, state that if the program goes forward, they will raise concerns with the U.S. State Department as it prepares its 2015 assessment of Thailand’s performance on trafficking in persons.

Last year, a Guardian series documented the horrors endured by migrant workers who often are tricked by labor recruiters and sold into bondage. Estimates of migrant workers in Thailand range from 200,000 to 500,000. In 2013, an ILO survey of nearly 600 workers in the Thai fishing industry found that almost none had a signed contract, and about 40 percent had wages cut without explanation. Children were also present aboard fishing boats.

Forced prison labor is not the solution to Thailand’s worker rights abuses, the organizations say in the letter to Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha.

“Simply replacing vulnerable migrant workers with released prisoners will not solve the abusive working conditions and many other problems present in the Thai fishing industry.”

Thailand is the world’s third-largest seafood exporter, and its fishery production accounts for $8 billion annually.

Jan 13, 2015

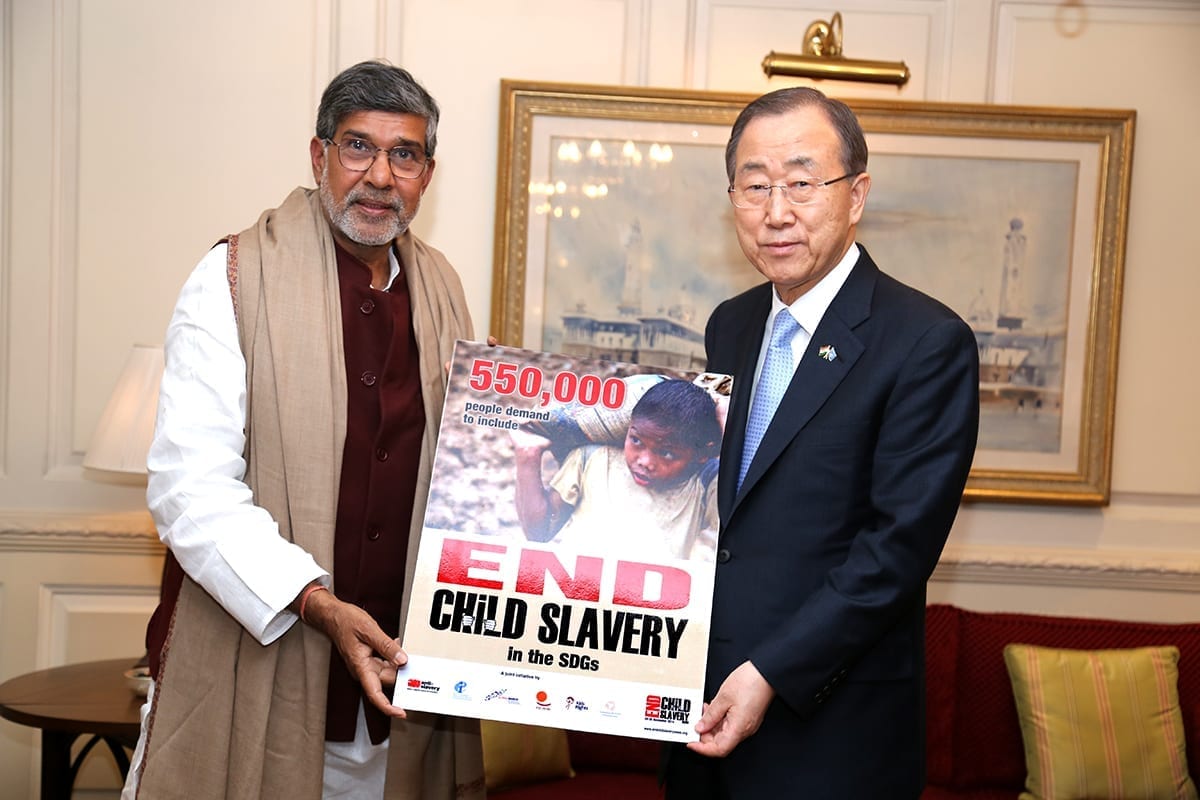

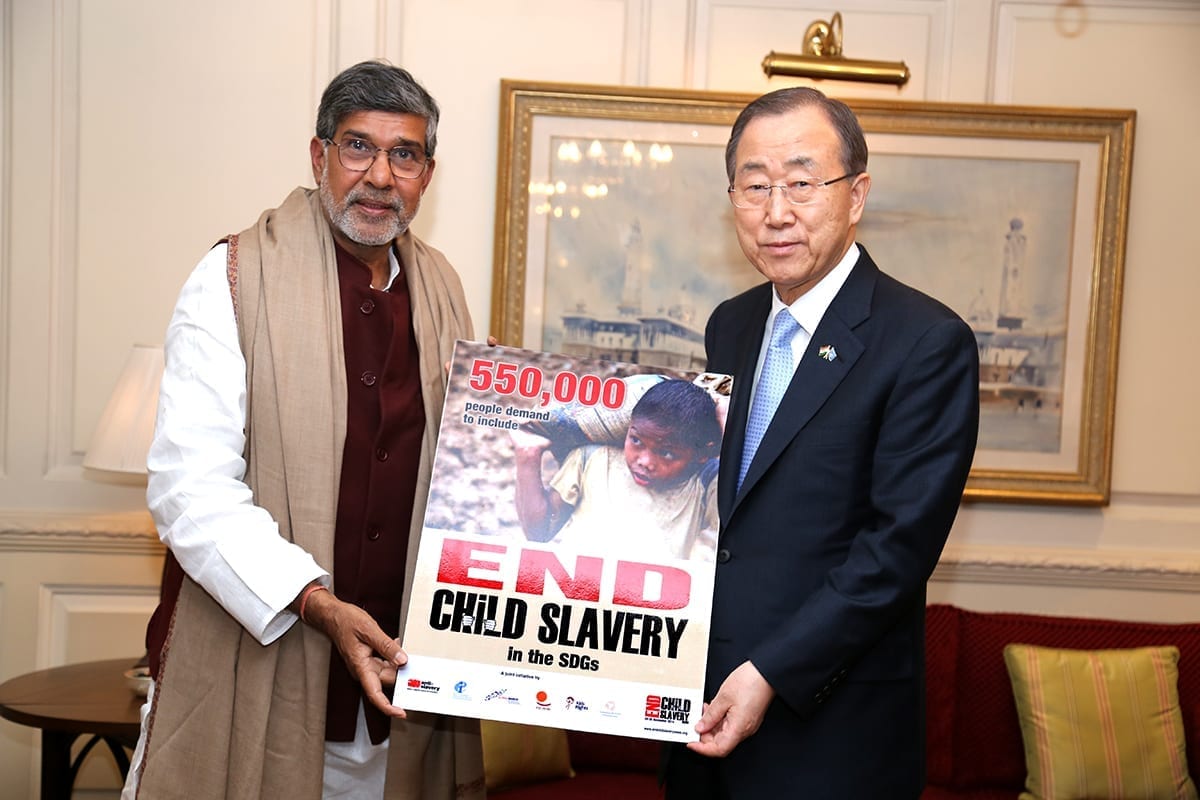

In an historic meeting, Nobel Peace Laureate Kailash Satyarthi delivered a global petition on child labor to United Nations (UN) General Secretary Ban Ki-Moon in New Delhi, India, yesterday. More than 550,000 people around the world signed the petition urging the UN to make abolition of child labor a key part of the world body’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), now under discussion.

“The most shameful commentary of today’s society is that slavery still exists, and our children are the worst sufferers,” Satyarthi said in an address at the event. “There cannot be any excuse for this heinous crime against humanity. There must not be any delay in ensuring their freedom. We have to act now and create a future where all children are free to be children.”

Last November, the Global March Against Child Labor, a coalition of unions and child rights organizations in more than 140 countries, which includes the Solidarity Center, launched End Child Slavery Week, to focus on improving the Sustainable Development Goals. The centerpiece of the campaign involved collecting signatures for delivery to the UN secretary general.

The petition included the exact text for inclusion in the “Outcome Document” of the Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals:

“Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labor, secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor including recruitment and use of child soldiers and child slavery, and, by 2025, end child labor in all its forms.”

Satyarthi, who in 1998 created the Global March Against Child Labor as part of his tireless efforts to end child labor, also discussed with UN officials at the event further steps for ensuring the rights of children globally. Satyarthi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014 for his decades of often dangerous work in rescuing child laborers and providing them with safe havens.

It’s not too late to sign the petition. In the United States, the social mobilization organization CREDO partnered with the Solidarity Center to create a successful petition campaign.

Sign now!

Jan 9, 2015

Five years after the catastrophic earthquake in Haiti, workers are still struggling to pay for transportation, food and housing, as the cost of living rises exponentially while wages fail to keep pace.

In recent discussions with export apparel workers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital, the Solidarity Center found that workers may pay nearly half their daily wage on two daily meals. Sending a child to school can absorb most of their monthly pay.

Elmerome, who makes T-shirts and is paid 225 Haitian gourdes ($4.81) per eight-hour day, says even though his wages have risen from 125 gourdes per day before the earthquake, food for himself and his child every day costs 500 gourdes, or more than twice his daily income. In 2013, he spent about 400 gourdes a day on food. Meanwhile, his child’s education costs run about 5,000 gourdes a month.

Like all workers whom the Solidarity Center interviewed, Elmerome is a member of a union, a factor he attributes to improving his working conditions. He says the Centrale National des Ouvriers Haïtiens (CNOHA) union has “helped fight against discrimination, suspensions and dismissals, and “gives workers a voice.” He sees freedom of association as the most important element for Haitian workers seeking to improve their working conditions. And echoing other factory workers interviewed, he says many workers fear joining a union because of employer harassment, including the threat of being fired.

The Solidarity Center held these recent informal discussions as a follow-up to a study it conducted in 2014 to reassess the cost of living for export apparel workers in Port-au-Prince. “The High Cost of Low Wages in Haiti” concluded that, based on a standard 48-hour work week, Haitian workers should be paid at least 1,006 gourdes per day to adequately provide for themselves and their families. But like Elmerome, workers are generally paid between 225 gourdes (the minimum wage for export factories) and 300 gourdes a day or more if they are piece-rate workers. Further, the report says,

“Despite growth at the industry level, export apparel workers remain impoverished …. Companies that source from Haiti benefit from inexpensive labor costs, as well as lax enforcement of labor laws in an industry that is rife with worker rights abuses.”

Another factory worker, Widnise, told the Solidarity Center that she makes 225 gourdes a day and spends nearly half of that—110 gourdes each day—on food and transportation. Even with two people working in her household, she says, it is difficult to survive. Her rent is 20,000 gourdes a year.

In 2013, Haitian workers and their unions waged rallies and protests to demand that the daily minimum wage be increased to 500 gourdes for export apparel workers, but the government raised it to only 225 gourdes, effective last June.

Since then, Haitian unions have sought to secure improvements for workers through labor-employer discussions with the government on reforming the current labor code, boosting social protections and reviewing wage levels. The current labor code has not been updated in more than 28 years, and union leaders say stronger labor laws and improved social protections could go a long way to address many of the problems facing Haitian workers and their families.

In the apparel sector, Haitian unions are actively participating with employers in the Social Dialogue Table launched in early 2014. Haitian government representatives from the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor Ministry participate as observers, along with other national and international organizations, including the Solidarity Center, the CTMO-HOPE Commission and the nonprofit, Better Work-Haiti. Union leaders say this process can potentially pave the way for improved workplace conditions, especially respect for worker rights.

“Our discussions with Haitian workers underscore a critical truth about the recovery effort: Subsistence wages have not helped workers surmount this disaster, much less allowed them to prepare for the next environmental or economic shock,” said Shawna Bader-Blau, Solidarity Center executive director. “For hardworking Haitians to live with dignity—and for Haiti to develop an economy that works for its people—fair wages are essential.”

The January 12, 2010, earthquake killed more than 200,000 Haitians and left another 1.5 million homeless. The disaster was followed by a string of tropical storms and a cholera epidemic that killed at least 8,000 people. Within days of the earthquake, the Solidarity Center dispatched regular truckloads of lifesaving emergency aid to Haiti from its field office in the neighboring Dominican Republic and carried out numerous aid and relief projects, together with allies like the American Federation of Teachers and TransAfrica. The report, “Workers Helping Workers Recover and Rebuild,” details the full range of the Solidarity Center’s multiyear relief and rebuilding effort in Haiti.

Jan 9, 2015

Agricultural workers in Meknes, Morocco, now have a first-ever collective bargaining agreement. Credit: Hind Cherrouk/Solidarity Center

The Confédération Démocratique du Travail (Democratic Labor Confederation, CDT) and the agro-industry employer, Les Domaines Brahim Zniber, signed a collective bargaining agreement today that covers nearly 1,000 agricultural workers on five large farms in Morocco’s fertile Meknes region. The pact follows a multi-year campaign by the CDT, with support from the Solidarity Center, to help workers in orchards, olive groves and vineyards improve their working conditions.

Under the agreement, agricultural workers receive bonuses if their work exceeds the norm. The agro-industry employer will provide safety equipment and social benefits, enabling workers to access worker compensation and other fundamental protections.

Moroccan Labor Minister Abdeslam Seddiki (standing, center), employer Rita Zniber and Bouchta Boukhalfa, the leader of CDT in Meknes (standing, left), take part in the signing ceremony. Credit: Colette Young/Solidarity Center

Crucially, this agreement– formalized during a ceremony with 400 workers, employers, labor leaders and government officials taking part–will guarantee their right to freedom of association and guarantees the rights of parties and social peace. In addition, this agreement will benefit all agricultural workers, especially women workers, who are active in this sector and represents an important percentage of the workforce. Les Domaines Brahim Zniber and the CDT are building bridges to extend similar agreements to other regions in Morocco.

“This agreement will ensure stability in employment,”says Abdelali Bouhiyadi, a union representative. “Even seasonal workers will keep their jobs and stay on the farms. Seasonal workers will be integrated gradually and the agreement will ensure social peace because a committee on conflict and negotiation will be established.”

Agriculture is a cornerstone of Morocco’s economy, with high-quality agricultural products, such as wine and olive oil, exported to Europe. Some 43 percent of workers in Morocco are employed in the country’s agriculture sector, and 40 percent are women.

“This agreement will allow us to have the opportunity to be trained in our jobs,” says Hayat El Khomssi, an agricultural worker.

The agreement is an important contribution to sustainable development and economic stability in Morocco, and will serve as a model for others to follow in Morocco and throughout the region. By taking this pioneering step and signing this agreement with the CDT, Les Domaines Brahim Zniber says it offers an example to other corporations that achieving world-quality products requires world-quality workers, and investing in workers is the most important investment corporations can make.

CDT leaders say this victory is an important step toward achieving the union’s vision of a sector-wide collective bargaining agreement for agricultural workers, one with the potential of improving the working conditions of all agricultural workers in Morocco.

Jan 7, 2015

Sumbawa, a rural region in eastern Indonesia, offers residents little opportunity to make a living, and many migrate to neighboring Malaysia and Singapore for work.

“If we don’t go, we don’t have a job,” says Pak Syamsul, who worked in Malaysia for more than two decades before returning to Sumbawa. “There really isn’t much employment here. Nothing. That’s why people leave.”

Globally, there are an estimated 232 million migrants in the world, the overwhelming majority who migrate for work. More than 6 million Indonesians work abroad, and in 2013, their remittances to their families brought $7.4 billion into the Indonesian economy.

Each of those migrant workers has a story, and a new film by JustJobs takes a close-up look at those who, like Syamsul, travel far to support their families. “Pulang Pergi” (“Going Home to Leave Again”), based on research supported by the Solidarity Center, illustrates the cost and opportunities for migrant workers and their communities.

Faisa Trisnawati, 27, is among those who migrated for a job. She worked two years in Jordan and six years in Saudi Arabia, financially unable to pursue her dream of higher education.

“I think a lot about the future, about my children, because I myself couldn’t get an education,” says Trisnawati, as her 4-year-old daughter, Nabila, played nearby. “My aspirations were never realized. I want my children to be able to accomplish anything. Not like me, becoming a migrant worker abroad …”

Working as a farmer in Sumbawa is impossible, she says, because the cost of renting land and buying supplies would exceed income. Rich with agricultural potential, Sumbawa highlights the complex and often conflicting pressures underlying global labor migration, a region that received $1.4 million in remittances in 2013 and where its residents are forced to leave.

The Solidarity Center is supporting research on key migrant worker rights issues–examining how workers migrate and under what terms–both of which are critical questions for global economic and social development. As a worker rights organization, we seek to advance labor migration that promotes shared prosperity by lifting up and empowering workers in both origin and destination countries.