Jun 24, 2015

Tens of thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent and Haitian migrant workers face imminent deportation from the Dominican Republic in a “crisis that has been building for many years,” says Cathy Feingold, AFL-CIO International Department director. “There is a long legacy of discrimination against workers and families of Haitian descent,” according to Feingold, who moderated a panel on the issue Tuesday in Washington, D.C.

“The Loss of Citizenship and Mass Deportation of Families of Haitian Descent from the Dominican Republic” brought together experts who discussed the nearly impossible hurdles Dominicans of Haitian descent were required to meet to qualify for a status that would allow them to apply for naturalization. June 17 was the deadline for registering with the government, which has not yet begun mass deportations.

Although the government advertised the registration process as free, saying only a handful of documents would be required, the reality has been far different, said Maritza Vargas, secretary general of SITRALPRO, the union for workers at the Alta Gracia Project in the Dominican Republic.

Speaking on the panel, she said when workers tried to register at government offices, they were first told they needed a couple documents—but later informed they needed up to 12 documents, the gathering of which comes at costs the equivalent of two or more months’ wages, sums that poor workers cannot afford. The hurdles are compounded by the Haitian government’s inability to rapidly provide documents and the Dominican government’s failure to open offices sufficiently staffed to handle registrations.

The Dominican government is justifying its move to deport Dominicans of Haitian descent by saying everyone had a chance to register, said Wade McMullen, staff attorney for Partners for Human Rights at the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Human Rights. Yet “the government created a system in which they can’t win. Under the guise of the rule of law, tens of thousands of Dominican citizens are being converted into undocumented migrants.”

Because of a 2013 Constitutional Court ruling, people born in the Dominican Republic—many of whom speak only Spanish and have never been to Haiti—must renounce their Dominican citizenship and apply for Haitian papers, said Lauren Stewart, Solidarity Center senior program officer for Dominican Republic and Haiti.

A 2014 report by the Solidarity Center and AFL-CIO called the ruling an “egregious abuse of fundamental human rights and a clear violation of international law.”

While a later presidential decree recognized the citizenship of roughly 68,000 people, an additional 130,000 Dominican natives who never had documents were forced to prove birth in the Dominican Republic to apply for Haitian citizenship and apply for regularization in the country of their birth with Haitian documents. Only about 10,000 of these people applied under the plan. Dominicans of Haitian descent and Haitian migrant workers constitute at least 6 percent of the Dominican population, Stewart said.

The Network of Support to Migrant Workers of the National Confederation of United Trade Unions (CNUS) and the Migrant Justice Movement are calling for the regularization plan to be extended at least until the end of year. The coalition, which includes unions and migrant organizations, formed at a 2014 advocacy training organized by the Solidarity Center. The Solidarity Center and its union partners have held trainings with workers on the regularization process and assist those seeking to register with the government.

Jun 22, 2015

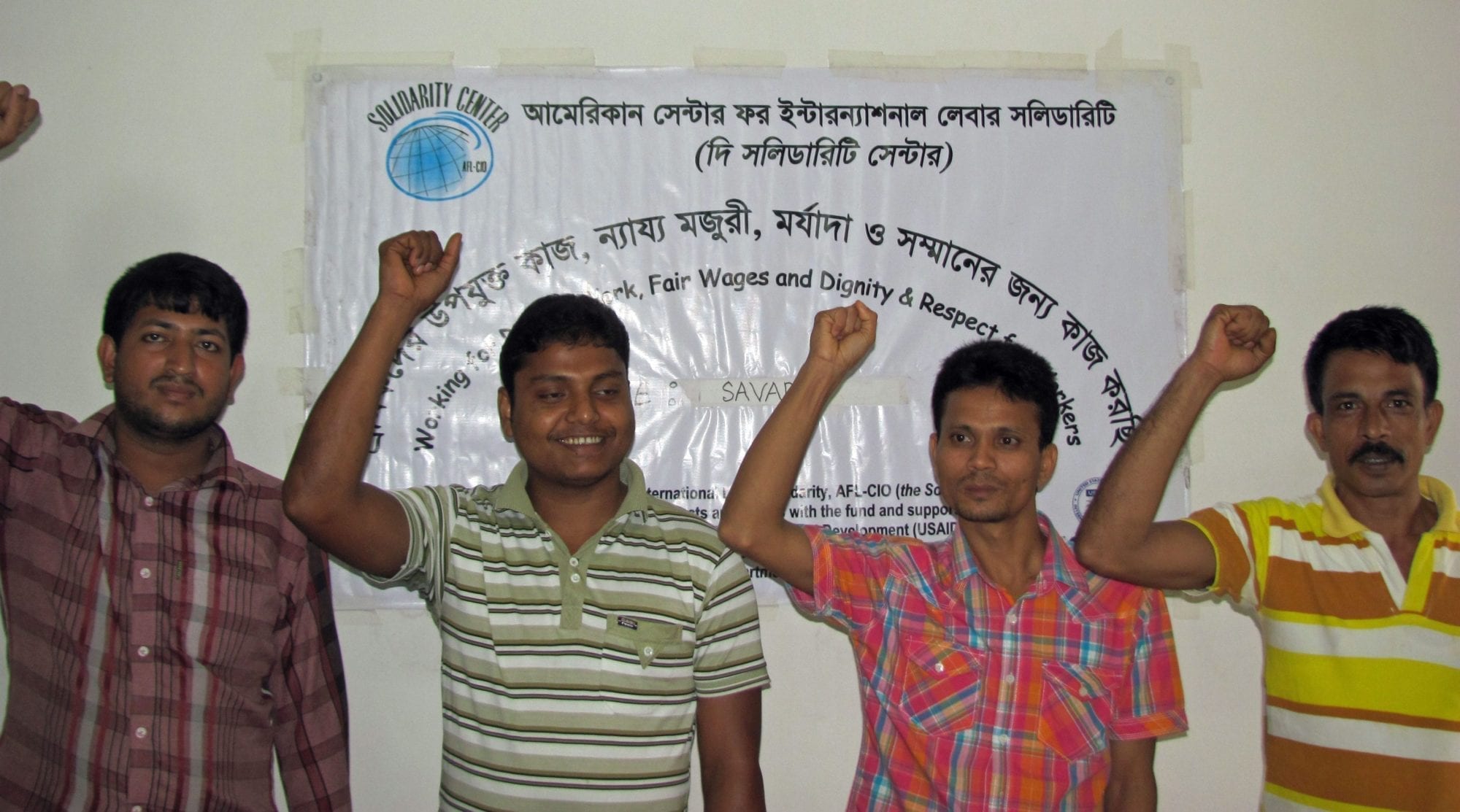

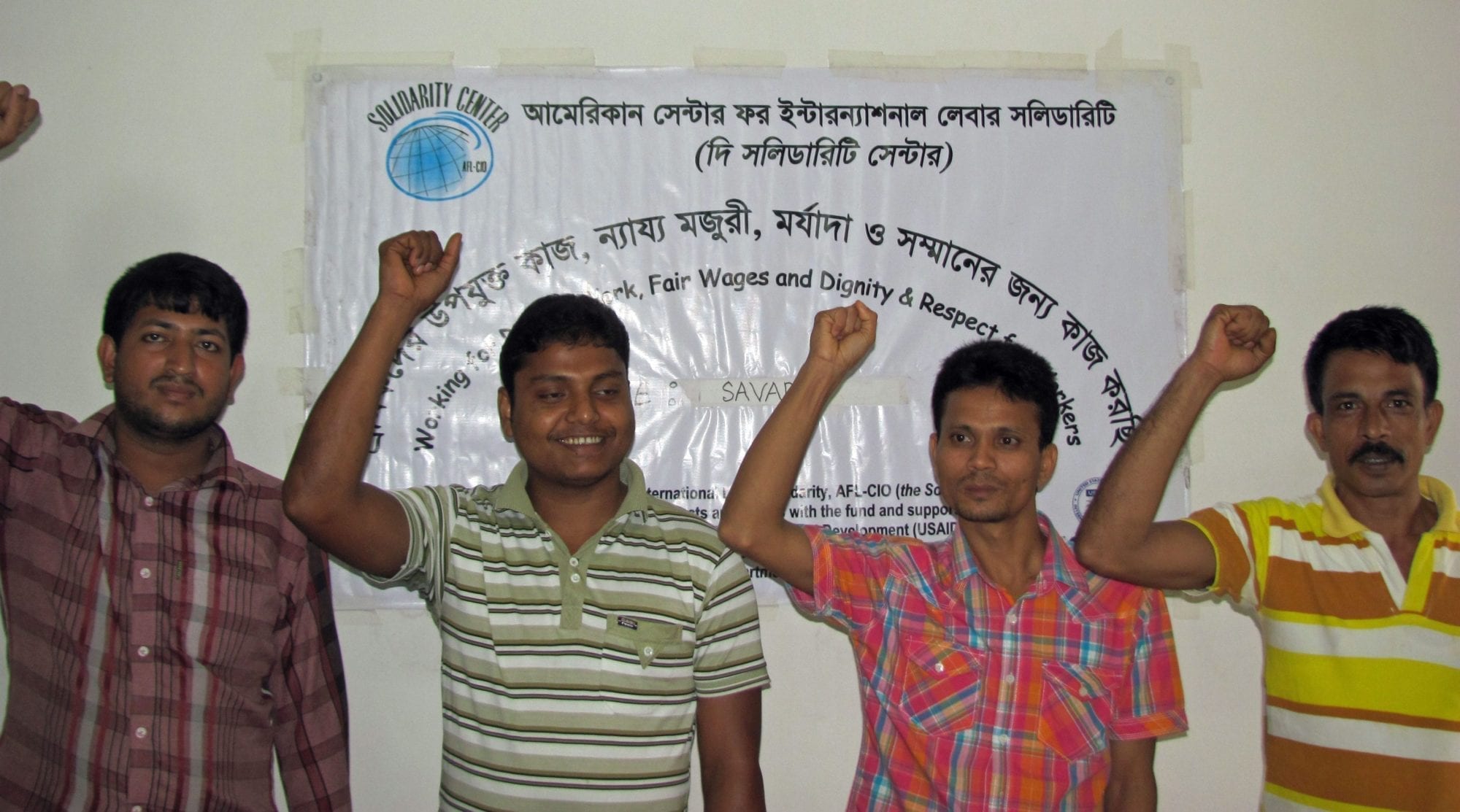

When Rafikul Islam, 25, president of a workers’ welfare association at a factory in the Dhaka export processing zone (EPZ) heard that one of the top factory officials harassed the female staff member responsible for the factory’s day care center, he took action.

“We called a meeting of our association and decided that we would protest this incident and write to the authorities to take action against the official,” Rafikul says. After they lodged a complaint, the official was terminated.

“This was possible because we were united. We never imagined such immediate action when there was no union in the EPZ.” Rafikul said there were similar incidents in other factories in the past but the victims did not get justice.

Despite obstacles, workers’ welfare associations are gaining ground in factories throughout Bangladesh’s export processing zones. Bangladesh derives 20 percent of its income from exports created in the EPZs, which are industrial areas that offer special incentives to foreign investors like low taxes, lax environmental regulations and low labor costs. Some 377,600 workers, the vast majority women, work in 497 factories in Bangladesh’s eight EPZs.

EPZ workers had long been denied the freedom to form unions, but in 2010, a law passed enabling workers to form unions under a different name—workers’ welfare associations. Associations are permitted to represent workers on disputes and grievances, negotiate collective bargaining contracts and collect membership dues. Now in the Dhaka EPZ alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers welfare associations.

But unlike traditional unions, the associations cannot interact nor affiliate with any labor union, nongovernmental organization or political organization outside the EPZ. Associations can only form a federation within one zone.

Kholilur Rahman, 20, general secretary of an association of another factory in the Dhaka EPZ says that after forming an association, workers became aware of their legal rights.

“Most of the workers in our factories were contractual workers,” he says. “Authorities did that purposefully to deprive us from receiving benefits. But after forming the association, the factory management made us permanent,” Kholilur said.

Oliur Rahman, a member of an association in the Dhaka EPZ, says that in the past, managers terminated them for trivial reasons.

“But this is not the case after we formed an association and voted for our association and elected the officers for our workers’ welfare association,” he said.

Jun 19, 2015

Solange Ambroise sells vegetables in the San Cristobal Municipal Market. Credit: Solidarity Center/Ricardo Rojas

Rarely do governments admit failing their citizens. However, on Friday the 193-member states of the United Nations did just that when they voted to rectify their failure to uphold the rights of workers and to ensure decent working conditions for more than half of the world’s working women and men.

By voting for an International Labor Organization (ILO) recommendation, The Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy, the large majority of the world’s governments has done more than just pledge to provide the basics for the world most vulnerable workers—those struggling to make ends meet in the informal economy—they have begun the essential process of strengthening society by promoting worker rights.

Street vendors, home-based workers, domestic workers and day-laborers usually work “off the grid” and outside a country’s regulations and labor laws. They join subcontracted, temporary and part-time workers who subsist on the fringes of the formal economy. These jobs typically pay low wages, perpetuate worker and human rights violations, provide limited or no social benefits, and offer little access to union representation. For most of these workers, survival trumps active engagement in society’s daily undertakings.

An estimated 1.5 billion, or approximately 60 percent of the world’s workers, toil in the informal economy, according to the ILO. In some developing countries, informal jobs comprise up to 90 percent of available work, and most workers take these unstable jobs out of necessity, not by choice.

Women, migrant workers and the young are disproportionately represented in the informal economy, and often the most exploited. Their situation is exacerbated because they may be barred from joining unions, which could offer support through collective bargaining on wages and working conditions, or because unions have not been able to reach them due to the isolated and changeable nature of their job.

Informalization of work fuels global income inequality, poverty and abuse. For example, at age 22, N. Naga Durga Bhavani left her small village in India for Bahrain, where she hoped a job as a domestic worker would help pay for her young daughter’s heart surgery. But when she arrived, after paying labor recruiters the equivalent of nearly two months’ wages, she says her passport and papers were confiscated, and she was forced to work long hours, trapped in an abusive environment where she was beaten, her fingers broken. After she escaped, the Indian Embassy could not help her leave the country because she had no identification.

And the drag on society does not end with the desperate plight of workers like Bhavani. Businesses employing workers in standard employer-employee relationships find themselves at a distinct disadvantage when they compete against those chasing short-term profits by not hiring full-time workers, paying taxes and benefits, or complying with regulations and labor law. Companies that provide financial and business services miss huge swaths of potential clients whose income leaves them too poor to enter the shop door and unable to access credit.

The effects on government are even more profound. The loss of tax revenue on huge percentages of GDP in many countries is only one edge of the sword. Because workers in the informal economy usually hang from the bottom rung of the economic ladder, they are more likely to need social safety nets—the very nets their jobs do not support through tax revenue.

Friday’s vote is significant because governments, worker representatives and employer representatives, who usually operate with very different agendas, publicly acknowledged the imperative of providing all workers with rights at work, social benefits and the ability to join a union. Their acknowledgement that the current system does not work—not for working people, not for governments and not for the businesses that serve them—is an important step toward bringing millions of workers into decent jobs that comply with labor codes and allow workers to be stronger members of their society. All of us should applaud the 193 nations for not choosing failure.

Jun 17, 2015

Hundreds of thousands of workers in the Dominican Republic without official identification papers have until today to register with the government or face deportation. The move—condemned widely as a violation of human rights—could leave as many as 120,000 Dominican-born and -raised women and men stateless, their future and their ability to earn a living jeopardized. If they cannot regularize their status, their next stop, as soon as tomorrow, may be the Haitian border.

Dominicans of Haitian descent have long faced exploitation and discrimination and experienced trouble obtaining official documentation, despite spending their entire lives in the country. Many speak only Spanish and have few, if any, ties to neighboring Haiti. However, a controversial 2013 Constitutional Court decision ruled that that individuals who were unable to prove their parents’ regular migration status could be retroactively stripped of their Dominican citizenship. While a later presidential decree recognized the citizenship of roughly 68,000 people, an additional 130,000 Dominican natives who never had documents were forced to prove birth in the Dominican Republic country to apply for Haitian citizenship and, with Haitian documents, apply for regularization in the country of their birth. Only about 10,000 of these people applied under the plan.

A 2014 report by the Solidarity Center and AFL-CIO, “Discrimination and Denationalization in the Dominican Republic,” called the ruling an “egregious abuse of fundamental human rights and a clear violation of international law.” Indeed, said the report, the actions by Dominican officials leading up to and following the ruling “demonstrate the depths of entrenched discrimination.”

In September 2014, Dominican unions and human rights groups raised concerns that the registration process was fraught with irregularities, unnecessary hurdles and bureaucracy. They said some local agencies were charging exorbitant fees for documents that were supposed to be provided for free and which applicants needed to demonstrate long-term residence. They said some workers had waited months for notification of the results of their applications, even though the law stipulates a response within 45 days.

Said Alexis Rosalie, spokeswoman for the National Coordinator for Immigration Justice and Human Rights and an organizer for the National Federation of Workers in Construction and Building Materials (FENTICOMMC), at the time: “We have proof there are people who meet all the basic requirements of the National Plan for Regularization of Foreigners (PNRE), and each time they go back to the offices, they are always told they are lacking one document or another.”

According to a report today by The Guardian newspaper, only 300 people applying for official identification received it.

Shawna Bader-Blau, executive director of the Solidarity Center, said: “We are astounded by this deliberate creation of a stateless underclass. Tens of thousands of people who live on the margins today and could be separated from their loved ones, their social networks, their jobs—all that is keeping them barely afloat—tomorrow.”

In past weeks, representatives of the Network of Support to Migrant Workers of the National Confederation of United Trade Unions (CNUS) and the Migrant Justice Movement, a grouping of unions and migrant organizations formed at a 2014 advocacy training organized by the Solidarity Center, held a series of press interviews calling for an extension to the regularization plan. Other groups, including Amnesty International, are calling on the government to respect international law and standards, and to “establish adequate mechanisms to avoid the expulsion of Dominican-born people who were deprived of their Dominican nationality in September 2013, including a specific screening process targeting Dominicans of Haitian descent.”

Jun 17, 2015

Nobel Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi led a rally against child labor at the Lincoln Memorial. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeff C. Wheeler

Saying that “168 million children are producing wealth, producing clothes, producing shoes, the things that you and I use,” child rights advocate Kailash Satyarthi told a crowd gathered yesterday at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.: “We are here to say that we denounce all forms of child slavery, of human slavery.”

On the 157th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech on slavery, Satyarthi, winner of the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize, spoke of the urgency with which child slavery must be eradicated. The Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation organized the meet-up for childhood freedom June 16, days after the global community marked World Day Against Child Labor.

Many of the 168 million child workers around the world are forced into slavery or prostitution or serve as child soldiers. Most, Satyarthi said, work in hazardous and even life-threatening conditions. While this number is down from 246 million in the 1990s, Satyarthi said there is still a long way to go.

“Every child should be free to be a child,” he declared. “Every child should be free to love, free to play, free to go to school, free to have a dream.”

Satyarthi called for organizations to work together to end child labor. “I have worked with civil society, I have worked with trade unions, I have worked with teachers’ organizations,” he said. He explained how such organizations are vital to promoting human rights, especially for children. “Companies like child labor because it is cheap, because children can be easily exploited,” he said. “Children cannot form unions, they cannot go to the polls.”

Satyarthi recalled the visions of freedom activists who came before him, including not only Abraham Lincoln but also Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela. “I feel pain,” Satyarthi said. “I am angry that we have not been able to pay the real tribute to these men by eradicating slavery.”

He also insisted that child labor and poverty could not be vanquished without serious investment in education. He lamented poorly financed school systems in some developing countries, where funds for education amount to less than three percent of gross domestic product. Children’s education also receives less than one percent of humanitarian aid worldwide, Satyarthi reported.

“We cannot have a just, dignified world without education,” he declared. “My children in the world cannot wait. Freedom must happen now.”