Oct 5, 2017

When Mwahamisi Josiah Makori, a Kenyan mother of three who worked as a domestic worker in Saudi Arabia, first arrived at her new employer’s house, she was given only 20 minutes before she began work. After that, she began a three-month period which involved hard labor, brutal sleeping conditions, and no pay. For three months, Makori cleaned two houses, took care of children, and was regularly beaten by her employers. Makori, who told her story to the Solidarity Center, now lives in Kenya after returning home after never receiving pay for her work.

Mwahamisi Josiah Makori, a Kenyan mother of three, was abused by her Saudi employer, who never paid her for her work. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

The conditions Makori faced, and which millions of workers around the world endure, fall outside the realm of what is called “decent work.” While all jobs come with inherent value, decent work entails jobs that are safe, pay living wages, take care of workers, provide breaks, and empower women.

This Saturday marks the 10th anniversary of World Day for Decent Work, which this year is focused on living wages, and the importance of minimum wages in ensuring that all workers can afford a quality standard of living. Some 80 percent of people surveyed around the world say the minimum wage in their country is too low, according to the International Trade Union Congress (ITUC), which spearheads World Day for Decent Work.

Makori and millions of others are forced to migrate for work because the only jobs available are in the informal economy, where low and unsteady pay, unsafe working conditions and lack of sick leave or other benefits often mean they cannot support themselves or their families.

More than half of all workers in the world are part of the informal economy, the majority of whom are women. By enabling informal economy workers, migrant workers, women workers and others traditionally excluded from union membership to join together to bargain collectively and demand their rights under the law, the Solidarity Center works to empower workers to raise their voice for dignity on the job, justice in their communities and greater equality in the global economy. Together in unions and worker associations, workers have the power to create decent work for themselves and ensure the work they do comes with dignity and economic justice.

Solidarity Center Standing up for Decent Work around the World

KUDHEIHA connects with community members in Mombasa during an education campaign on migrant worker rights. Credit: Solidarity Center/Deddeh Tulay

Recently in Kenya, the Kenya Union of Domestic, Hotel, Educational Institutions, Hospitals, and Allied Workers (KUDHEIHA), a Solidarity Center partner, made key progress in its struggle to strengthen the rights of workers who migrate from the country for work. Labor brokers often give workers false information about the wages and working conditions in other countries. A new proposal, crafted by Kenya’s Labor Ministry and KUDHEIHA, would require employers to provide workers with their contracts up front, so that there is no question of what workers should expect before they leave.

Elsewhere, Solidarity Center programs further advance rule of law and gender equality in unions and communities. In Iraq, for instance, union leader Sultan Mutlag Ahmed participated in a Solidarity Center labor law training and so was equipped to bring justice to construction workers by winning back their unpaid wages through a successful court case.

The Solidarity Center also is part of a global campaign to combat gender-based violence at work, one of the most tolerated abuses of workers’ rights. Together with the ITUC and global allies, the campaign seeks to build critical support for the adoption of an International Labor Organization convention on gender-based violence.

As unions around the world stand up for decent work October 7, you can support and follow the actions on Twitter with the hashtag #WDDW and #OurPayRise. Also check out the ITUC’s World Day for Decent Work to download logos and infographics.

Nov 15, 2016

In Binga, a small community 400 miles west of Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital, residents support themselves and their families fishing the vast Lake Kariba. With no industry in the area, they depend on the lake for their livelihoods. Yet they say they face constant challenges in making a living—the biggest of which is harassment from officials.

“We are oppressed by the … authorities. Our fish are confiscated”—Alice Mudenda, a fisher in Binga Credit: ZCIEA

“We are oppressed by the … authorities,” says Alice Mudenda, a fisher in Binga. “Our fish are confiscated by either the police, rural district council or National Parks officials under unclear circumstances.”

Binga fishers must have a license to fish—yet it only can be obtained in Harare, an eight-hour journey, and the cost, up to $2,000 every three months, is well beyond their means.

Some 94 percent of Zimbabwe workers make their living outside the formal economy, and yet like Mudenda, they say they are harassed and bullied by authorities, according to a survey by the Zimbabwe Chamber of Informal Economy Associations (ZCIEA), a Solidarity Center ally.

81% of Zimbabwe Informal Economy Workers Bullied or Threatened

Eighty-one percent of the 514 respondents say they have been bullied, with 22 percent specifying that the harassment involved both confiscation of goods and threats of violence.

Some 36 percent noted the source of harassment stemmed both from the local authorities and the Zimbabwe Republic Police, the national police force of Zimbabwe, with 32 percent citing local authorities as the biggest source of harassment.

The ZCIEA survey also found widespread fear and distrust of law enforcement officers, with 82 percent of respondents saying they had not reported their harassment to police because police are the harassers (46 percent) or they fear police (17 percent).

Market Vendor Law Targets Livelihoods

In June, the Zimbabwe government introduced a statutory law that bans imports of basic commodities—a law that directly affects hundreds of thousands of informal economy workers who survive on cross-border trading. Merchants in towns like Beitbridge, which borders South Africa, reported plummeting sales after the law’s passage.

Tens of thousands of market vendors protested the new law, joined by civil servants outraged over the government’s refusal to pay their salaries, holding a successful one-day shut-down of businesses, government and services July 6.

The survey covered 25 areas across the country, with 53 percent of respondents women and 40 percent men (7 percent did not answer). The majority are between ages 35 and 44 (35 percent), followed by 25–34 years (27 percent) and 45–54 years (16 percent).

ZCIEA was formed in 2004, when the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU)/Commonwealth Trade Union Council (CTUC) project began working with 22 trader associations to launch an umbrella organization to better coordinate efforts.

ZCIEA, with 198,466 registered members, offers training and legal support, along with legislative advocacy. In the report, the association points to the need to address the widespread harassment of informal economy workers by developing programs that further empower members, including workshops on legal rights and representation and preventing sexual harassment.

Jul 15, 2016

An astounding 80,000 Zimbabwe workers in formal employment—out of some 350,000 workers—did not receive wages and benefits on time in 2014, according to a new Solidarity Center report, “Working Without Pay: Wage Theft in Zimbabwe,” released today in Harare.

As a result of this widespread wage theft, many workers say they are forced to eat only one or two meals a day; move repeatedly to access affordable housing; and rent two rooms or fewer for their entire family to make ends meet.

As a result of this widespread wage theft, many workers say they are forced to eat only one or two meals a day; move repeatedly to access affordable housing; and rent two rooms or fewer for their entire family to make ends meet.

Through first-person interviews and other research by affiliates of the country’s main trade union confederation, the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU), the report provides hard data behind last week’s successful one-day shut-down of businesses, government and services by workers across Zimbabwe outraged over wage theft and a new law targeting market vendors who make up the vast proportion of the workforce.

Paid Only Enough to Get to Work

One woman interviewed in the report, whose experience is not uncommon, says she has received $26 a month in wages for the past eight months, although her monthly salary is $342. Yet basic living costs, which on average include $60 for renting a single room, $30 for electricity, $15 for water and $22 for transportation to work, mean she only has sufficient funds to get to and from her job.

“This failure to pay what workers are legally entitled to is wage theft in that it involves employers taking money that belongs to their employees and keeping it for themselves,” the report states. “This is a clear violation of international labor standards, as well as national legislation on the employment of workers.”

The report traces the ongoing wage theft to 2012, as employers in the public- and private-sector increasingly began delaying wage payments.

Up to 95% of Zimbabweans Work in Informal Economy

Simultaneously, the number of jobs in the informal economy has skyrocketed, the report points out. Some 6.3 million people made up Zimbabwe’s workforce in 2014, of which 5.9 million workers (94.5 percent) were informally employed, compared with 84.2 percent in 2011, according to “Working without Pay.” An additional 800,000 women and men were in the workforce, but unemployed.

Last month, the government introduced a statutory law that bans imports of basic commodities—a law that directly affects hundreds of thousands of informal economy workers who survive on cross-border trading. Up to 95 percent of jobs in Zimbabwe are in the informal economy, and workers say the new law takes away their livelihoods.

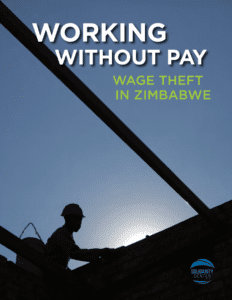

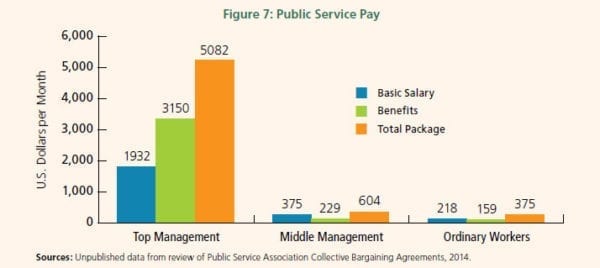

Based on surveys at 442 companies, and the result of extensive research by the Labor and Economic Development Research Institute of Zimbabwe, the report also documents extravagant salaries and benefits to middle and top management even as workers go unpaid and presents recommendations for action to address the problem.

Companies Involved in Wage Theft Must Be Held Accountable

Some of the recommendations include:

- The Ministry of Labor, together with representatives of employers and unions, should review the status of companies that are not paying their workers and assist in developing plans to rectify the injustice.

- Unions representing workers in companies not paying salaries—in full and on time—should demand that the government bring criminal proceedings under the relevant provisions of the Labor Act against employers.

- Trade unions should advocate for payment of interest on late payment.

- The government should set an example by reviewing the wage structure in government agencies and quasi-government agencies to limit benefits to top managers, institute a more just pay scale and prioritize payments to workers through collective bargaining or social dialogue.

Aug 12, 2015

“Organizing campaigns that are led by migrant workers themselves are making the impossible possible,” says Tefere Gebre, AFL-CIO executive vice president, succinctly summing up the discussion that opened the second day of the conference Labor Migration: Who Benefits?

“When workers come together, it doesn’t matter if you are a native or a migrant. If we don’t protect work for migrant workers, all workers are threatened.”

“If we don’t protect work for migrant workers, all workers are threatened.”–AFL-CIO Executive Vice President Tefere Gebre Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

Gebre joined panelists at the session on Migrant Worker Voice, Activism and Organizing, part of the August 10–12 Solidarity Center conference on labor migration in Indonesia.

He discussed how U.S. unions are partnering with migrant worker rights groups to win collective bargaining agreements and further empower workers, a strategy that Alejandra Ancheita, executive director of ProDESC (Project for Economic, Cultural, and Social Rights), a Solidarity Center ally, says is key to success in Mexico where she works.

Ancheita, winner of the prestigious international Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders, discussed how U.S. and Mexican labor rights organizations are working in a cross-border justice alliance to support seasonal workers in the northern state of Sinaloa.

“That has given birth to an organization of seasonal workers that includes a profound analysis of the legal framework in both the United States and Mexico that they can use in defense of their legal rights.”

Alejandra Ancheita is director of the Mexico-based ProDesc, which organizes workers before they migrate so they know their rights. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

Key to migrant worker empowerment, Ancheita says, is organizing workers and educating them about their rights before they leave the country.

“When migrant are organized in their countries of origin, they are empowered to stand up for their rights in the destination countries,” she says. “This organizing among workers in their origin countries also helps workers have a more global perspective and more of a strategy for defending their rights.”

Myrtle Witbooi, president of the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) and a former domestic worker, made the connection between organizing domestic workers and migrant workers, with both groups “undervalued, underpaid and exploited.”

“In the international domestic workers network, we have a policy to educate our domestic workers to understand they have legal rights in whatever country they are going to. As we grow, we can ensure that migrant workers are recognized. Our role is to spread this message to the world.”

“We can ensure that migrant workers are recognized. Our role is to spread this message to the world.”–IDWF President Myrtle Witbooi. Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

Witbooi, who last week was named a winner of the Global Fairness Initiative’s Annual Fairness Award, in 2013 accepted the AFL-CIO’s George Meany-Lane Kirkland Human Rights Award on behalf of the IDWF.

Rounding out the panel, Colin Rajah, coordinator and co-founder, Global Coalition on Migration, focused on the role of labor recruiters in the migration process.

The coalition, an open network of 90 members in 40 countries, brings together unions and human rights groups that agree the recruitment industry “is in dire need of fundamental changes,” says Rajah.

“As migrant workers, we need to take control of the process and do that in unity.”

Rajah says recruitment reform currently is not a high priority for the Global Forum on Migration Development (GFMD) this year, but he anticipates it will be in the next year or two and the coalition is working to ensure it is. The GFMD is a non-binding and government-led process open to United Nations member states and observers “to advance understanding and cooperation on the mutually reinforcing relationship between migration and development and to foster practical and action-oriented outcomes.”

More than 200 participants are taking part in Labor Migration: Who Benefits? A Solidarity Center Conference on Worker Rights & Shared Prosperity.

Follow the conference on the website and on Twitter @SolidarityCntr.

Aug 11, 2015

Participants in Monday’s final session of the Solidarity Center labor migration conference engaged in a lively discussion with panelists in a discussion of migrant workers’ vulnerability to gender-based violence.

Lisa McGowan, senior specialist for gender equality, outlined the broad picture, pointing out that gender-based violence is “one of the most widespread human rights violations in the world,” and migrant workers are especially at risk of gender-based violence because they are often invisible.

“Domestic workers suffer violence for being women, migrants and indigenous people.”–Marcellina Bautista, leader of the Center of Support and Training for Domestic Workers.

Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

Describing her work organizing and supporting domestic workers, many of whom are migrants, Marcellina Bautista, the leader of the Center of Support and Training for Domestic Workers (CACEH), said that “domestic workers suffer violence for being women, migrants and indigenous people.”

Bautista, who worked as a domestic worker for many years, says domestic workers encounter “all kinds of violence in the homes where we work.”

“The majority of the 2.3 million people in Mexico who do domestic work are women and girls” who are highly vulnerable to gender-based violence, says Bautista, who also serves as International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) regional coordinator for Latin America.

The CACEH works with domestic workers who face workplace violence, helping migrant workers understand that they have the same rights as other workers in Mexico.

Farm work is another sector where women workers are especially vulnerable to gender-based violence, and Agatha Schmaedick Tan discussed the Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ (CIW) efforts to end sexual harassment and violence among tomato pickers in Florida. Tan cited a study that found some 80 percent of female farmworkers had experienced sexual harassment at work in 2010.

“Sexual harassment on the job persists worldwide,” Agatha Tan, counsel for the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

Describing Immokalee, Florida, as “not a town, but a labor reserve,” Tan outlined CIW’s path breaking Fair Food Program, which CIW negotiated with growers and which 14 major corporations have signed. Under the code, which covers as many as 100,000 workers in a year, farms must comply with fundamental labor standards, including preventing violence and sexual harassment at work. Corporations agree to buy only from farms that comply, and auditors annually evaluate the farms. Some 90 percent of Florida tomato growers have signed on to the program.

“Sexual harassment and violence on the job is illegal in most countries, yet sexual harassment on the job persists worldwide due in part to the difficulties of enforcement,” she said.

Closing the panel, Chidi King, International Trade Union Confederation Equality Department director, told participants: “We as a labor movement have not done enough to bring (gender-based violence at work) to the fore of our agendas. We still see this as a personal issue,” not one to be dealt with at the organizational level.

Chidi King, ITUC Equality Department director, rallied participants to push for an ILO standard on gender-based violence at work. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

King noted that the ILO has not taken up gender-based violence because of resistance of “very regressive governments,” and urged participants to push the ILO to create a standard covering gender-based violence.

“When you’re talking about your organization’s activities, have this front and center. It cannot be an issue we continue to remain silent about.”

More than 200 participants are taking part in the Aug. 10-12 event, Labor Migration: Who Benefits? A Solidarity Center Conference on Worker Rights & Shared Prosperity.

Follow the conference on the website and on Twitter @SolidarityCntr.