Oct 10, 2014

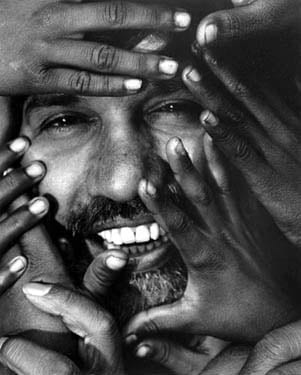

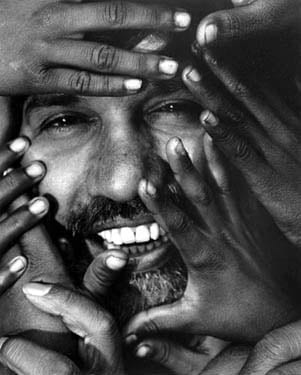

Labor and human rights activist and long-time Solidarity Center ally Kailash Satyarthi won the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize, the Nobel committee announced this morning. He shares the prestigious award with Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani girl who survived a brutal 2012 Taliban attack for her stance on girls’ education.

As a grassroots activist, Satyarthi has led the rescue of more than 78,500 child laborers and survived numerous attacks on his life as a result. As a PBS profile describes Satyarthi’s work: “His original idea was daring and dangerous. He decided to mount raids on factories—factories frequently manned by armed guards—where children and often entire families were held captive as bonded workers.”

Solidarity Center Asia Regional Director Tim Ryan said, “Kailash’s lifetime commitment to the cause of eradicating child labor is an inspiration to every human rights defender around the world to promote the rights of the most vulnerable, the most economically exploited young workers and the paramount importance of finding ways to secure basic education for all children around the world.”

Satyarthi’s decades of work to end exploitive child labor have encompassed advocacy for decent work and working conditions for adults, including domestic workers, because impoverished families must often make the difficult choice of sending their children to work for the sake of family survival.

“Child labor is a largely neglected, ignored, denied aspect of human rights,” Satyarthi told the Solidarity Center in a recent interview. “This is crime against humanity and is unacceptable in any civilized society.”

In 1998, Satyarthi created the Global March Against Child Labour, a coalition of unions and child rights organizations from around the world, to work toward elimination of child labor. Global March members and partners are now in more than 140 countries. Many of these civil society groups, including the Solidarity Center, came together to launch End Child Slavery Week November 20–26, with the focus this year on pushing the United Nations to make ending child labor a key priority of its 15-year action now under development.

Winning the Nobel “will help in giving bigger visibility to the cause of children who are most neglected and most deprived,” Satyarthi said upon learning he won the prestigious prize. “Everyone must acknowledge and see that child slavery still exists in the world in its ugliest face and form. And this is crime against humanity, this is intolerable, this is unacceptable. And this must go.” (Listen to his interview with the Nobel Prize team.)

At age 26, Satyarthi gave up a promising career as an electrical engineer and dedicated his life to helping the millions of children in India who are forced into slavery by powerful and corrupt business and land owners.

In 1994, Satyarthi spearheaded Rugmark (now known as GoodWeave), the official process certifying that carpets were not woven by children, and aimed at dissuading consumers from buying carpets made by child laborers through consumer awareness campaigns in Europe and the United States.

His life’s achievements encompass a range of human rights work. Satyarthi created a series of “model villages” free from child exploitation, and some 356 villages have emerged in 11 states of India since the model’s inception in 2001. The children of these villages attend school and participate in a wide range of governance meetings to discuss the running of their villages, through child governance bodies and youth groups.

“Showing great personal courage, Kailash Satyarthi, maintaining Gandhi’s tradition, has headed various forms of protests and demonstrations, all peaceful, focusing on the grave exploitation of children for financial gain,” said Nobel Committee Chairman Thorbjorn Jagland said.

Satyarthi’s award of the Nobel Prize is the latest high-profile recognition of worker rights activists in the last month. Earlier this week, Alejandra Ancheita, founder and executive director of the Mexico City-based ProDESC (Project for Economic, Cultural, and Social Rights), won the prestigious international Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders. And in September, Ai-jen Poo, founder and director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, became a MacArthur ‘Genius’ Grant recipient.

Sep 19, 2014

Three times each month, dozens of women gather in dusty courtyards in rural towns in Manikganj, Dinazpur or other districts across Bangladesh to learn all they can about the only means by which they can support their families: migrating to another country for work.

In leading these information sessions, the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA) seeks to assist women in understanding their rights—from what they should demand of those who facilitate their migration, to the wage and working conditions at the homes in Gulf and Asian countries where they will be employed as domestic workers.

“What I want for these women is that they are safe, they get their wages,” said Sheikh Rumana, BOMSA general secretary. Rumana founded the organization in 1998 with other women who worked with her for years in Malaysian garment factories. Before she migrated for work in Malaysia, Rumana was promised a good salary at an electronics plant. But when she arrived, she was put to work at a plant making jackets and paid pennies for each piece she sewed.

The gap between the promise and reality of migrating for work overseas is the focus of migrant worker activists across Asia. This month, Rumana and seven other migrant worker activists from Bangladesh, India and the Maldives are traveling across the United States as part of a Solidarity Center exchange program supported by the U.S. State Department. The group is meeting with U.S. activists working on labor rights, migrant rights and anti-human trafficking issues in Washington, D.C., New York and Los Angeles to discuss best practices to promote safe migration and share ideas for raising awareness about the risks of migrating for work.

Like BOMSA, the Welfare Association for the Rights of Bangladeshi Emigrants Development Foundation (WARBE-DF) assists those seeking to migrate, provides support for workers overseas and assists them upon their return. The organization also has successfully pushed the Bangladeshi government to ratify the United Nations (UN) convention on the protection of migrant workers, and is campaigning for passage of the International Labor Organization (ILO) convention covering decent work for domestic workers, said Jasiya Khatoon, WARBE-DF program coordinator and Solidarity Center exchange participant.

“Lack of job opportunities” is what drives millions of Bangladeshis out of their country in search of work, Khatoon said. Some 8.5 million Bangladeshis are working in more than 150 countries, according to 2013 government statistics.

Many workers migrating from Bangladesh and elsewhere are first trafficked through another country—where a lack of proper documentation may result in their arrest. In Mumbai, India, a transit point for many migrants, human rights lawyer Gayatri Jitendra Singh works both to assist imprisoned migrant workers and to change the country’s laws so that, rather than penalizing migrant workers, the laws recognize the culpability of traffickers and corrupt labor brokers.

Singh, a former union organizer, and other migrant advocates, point to the actions of labor brokers as the biggest underlying problem in the migration process. Many labor brokers charge such exorbitant fees for securing work that migrant workers cannot repay them even after years on the job, essentially rendering them indentured workers. They remain trapped, often forced to remain in dangerous working conditions because their debt is too great. Unscrupulous brokers also lie about the wages and working conditions workers should expect in a destination country, the migrant advocates say.

Singh and the other migrant advocates came to the United States filled with fresh stories about the suffering of migrant workers and their families: a Bangladeshi domestic worker in Jordan and another in Lebanon who had just returned to Bangladesh, still suffering the effects of nightly sexual abuse by their employers; the family of an Indian construction worker who died in Qatar and is unable to pay for the return of his body; the 12-year-old Bangladeshi girl whose passport cites her age as 25 so she can migrate overseas to support her family because her father is ill.

Bangladeshis “wouldn’t go if there were jobs in their country,” said Rumana. But faced with grinding poverty and no chance for decent work in Bangladesh, they uproot their lives to make a living. But as long as they do, Rumana said, they “shouldn’t have to be tortured to have work.

Mar 6, 2014

Self-employed bidi rollers in India have access to social services because of SEWA’s efforts. Credit: SEWA

Each day this week leading up to International Women’s Day March 8, the Solidarity Center will highlight an example of how women and their unions are taking action to improve women’s lives on the job, in their unions and in their communities.

India passed a landmark Street Vendors Act this month that, for the first time,recognizes the country’s 40 million street vendors as workers deserving of rights and labor law coverage equal to all other wage earners.

Behind the passage of the Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending Act are decades of struggle by a dedicated group of women who in 1972 began organizing women workers in informal economy jobs like home-based cigarette (bidi) rollers. Today, the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) includes 1.7 million women workers across the country, 200,000 of whom are street vendors.

“This is a proud moment for us at SEWA as we have struggled hard to improve the situation of street vendors, many of them women who were earlier denied the right to a respectful livelihood and subjected to severe exploitation,” says SEWA National Secretary Manali Shah.

SEWA members and allies waged a hunger strike in New Delhi and took other action to press lawmakers in India’s upper house of Parliament to pass the bill, which the lower house approved last year. Their actions exemplify the type of public education and outreach members have undertaken to make visible workers who are not accorded the same rights and protections as those employed in formal sector jobs.

SEWA members are among the most marginalized of India’s workers: Self-employed, their income is unpredictable and few receive social welfare benefits, unlike workers in formal-economy jobs. More than 94 percent of women workers in India work in the informal-sector economy.

The union began when five women went door to door to learn the most pressing issues for self- employed women, said Geeta Koshti, a coordinator in SEWA’s legal department. The early SEWAorganizers then identified women who could take leadership roles, and they recruited local organizers who, as trusted members of their communities, could better connect with women workers.

Women who join with SEWA go on to form their own local trade union councils where they make decisions about the types of campaigns they want to pursue and hold trainings on membership education and leadership development. Some have created worker cooperatives and other organizations to assist their members.

SEWA is very much a member-driven organization, said Koshti, and the union prioritizes its efforts in accordance with its members. For instance, if workers say they want clean water, the union does not run other unrelated campaigns.

From a handful of women in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, SEWA has expanded to represent women in 14 Indian states. One of SEWA’s most successful endeavors involves women in the bidi trade. Koshti, whosemother was a bidi roller and SEWA member, said SEWA’s multiyear efforts culminated in a Bidi Welfare Board, one of the few such institutions for workers in the informal sector. The board is responsible for implementing a benefits program that allows bidi workers to have access to social services, such as healthcare and educational scholarships for children.

SEWA, which its leaders describe as both an organization and a movement, includes programs such as a shareholder organization to assist artisans in marketing their crafts and a microcredit bank.

Koshti adds that SEWA’s integrated, holistic approach addresses all the issues women face, such as child care. In short, the union is driven by a real strong commitment to ensure members are involved.

Oct 7, 2013

At age 22, N. Naga Durga Bhavani left her small village in India for Bahrain, where she hoped a job as a domestic worker would help pay for her young daughter’s heart surgery. But when she arrived, after paying labor recruiters the equivalent of nearly two months’ wages, she says her passport and papers were taken and she was forced to work long hours, trapped in an abusive environment where she was beaten, her fingers broken.

After she escaped, the Indian Embassy could not help her leave the country because she had no identification. Only through the efforts of the Migrant Forum in Asia and the National Domestic Workers Movement in India, both Solidarity Center partners, did Bhavani’s employer relinquish her passport, allowing her to return home. Bhavani’s experience as a migrant domestic worker is not unique—nor can her employment be called “decent work.”

Today, millions of union members and their allies around the world are marking World Day for Decent Work 2013 to highlight the plight of workers like Bhavani and the millions who toil for poverty-level wages in exploitative working conditions that are unsafe, unhealthy and even life-threatening. Among them are Bangladesh garment factory workers who face locked doors when fires break out; female pineapple workers who experience sexual harassment on Honduran plantations; and Liberian rubber workers forced to carry hundreds of pounds of raw latex across plantations.

It took two months before Bhavani’s employer returned her passport, said Lissy Joseph, national coordinator of National Domestic Workers Movement. Joseph and eight other migrant worker activists, all of whose organizations are members of the Migrant Forum in Asia, were in the United States for the Oct. 3-4 United Nations High-level Dialogue on International Migration and Development. They traveled to Washington, D.C., last week and met with Solidarity Center staff, as well as U.S. government representatives.

Migrant workers, many of whom are domestic workers, are among the most exploited in the world. Yet, “we cannot stop people from migrating because that is the means to their livelihood,” says Joseph. So she and other members of the Migrant Forum in Asia, a regional network of trade unions, non-government organizations (NGOs) and associations, promote the rights and welfare of migrant workers by addressing discriminatory laws and policies, violence against women migrants, unjust living conditions, unemployment in the origin countries and other issues. In short, they are moving forward with the World Day for Decent Work imperative: Organize!

“Our concern in working together is the solidarity of workers around the world,” says Joseph.

The exorbitant and exploitative fees labor recruiters often charge migrant workers and the abusive conditions workers can face after arriving in destination countries are two of the biggest problems for those forced to leave their countries to make a living, the migrant activists told the Solidarity Center. In fact, roughly three migrant workers from Nepal die each day—from abuse, exposure to unfamiliar climates and even suicide, said Nilambar Badal, from the Asian Human Rights and Culture Development Forum Migrants Center in Nepal.

Although destination countries and origin countries may have solid laws for protecting labor rights, too-often they are not enforced. “There is still a big gap in terms of the reality on the ground,” said Ellene Sana, a policy advocate for the Center for Migrant Advocacy in the Philippines, a country that officially says 1.8 million of its citizens are migrant workers, mostly in the Middle East.

And while working conditions frequently are bad for migrant workers, when they return home, there are no jobs “so they re- migrate and the cycle of abuse continues,” said Sanjendra Vignaraja, Solidarity Center program officer in Sri Lanka. In India, there is now a “greater disparity between haves and have nots,” said Joseph.

But India is not unique. Across the globe, the increasing wealth gap often leaves workers with few options, many of which cannot be called decent work. Which is why organizations that bring workers together for a stronger voice are so critical.

Sep 24, 2013

This report details a set of case studies on collective bargaining by informal workers in four different countries: Waste pickers in Minas Gerais state in Brazil, beedi workers in India, Georgia minibus taxi workers and street vendors in Monrovia, Liberia. The study also references the efforts of domestic workers in Uruguay.

Download here.