Dec 2, 2015

The following is crossposted from Equal Times.

On November 18, 2015, Norway ratified the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Forced Labor Protocol, which strengthens and updates the 1930 Forced Labor Convention (Convention 29) by adding new measures to prevent, protect and compensate those affected.

According to ILO data, some 21 million people globally are victims of forced labor, generating approximately $150 billion each year. However, the hidden nature of this and other forms of extreme labor exploitation mean the true figures could be much higher.

By becoming the second country in the world after Niger to sign the UN treaty, Norway has ensured that the Protocol will be brought into force next November.

“Norway’s ratification will help millions of children, women and men reclaim their freedom and dignity,” said ILO Director-General Guy Ryder in a statement. “It represents a strong call to other member states to renew their commitment to protect forced laborers, where ever they may be.”

Renée Rasmussen, Confederal Secretary of the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions, said: “The world has changed dramatically since 1930, but in many societies the issues that Convention 29 was created to deal with are still unpleasantly current.”

Although 56 per cent (11.7 million), 18 per cent (3.7 million) and 9 per cent (1.8 million) of all forced labourers are found in Asia, Africa and Latin America respectively, the reach of modern-day slavery crosses countries, continents and sectors.

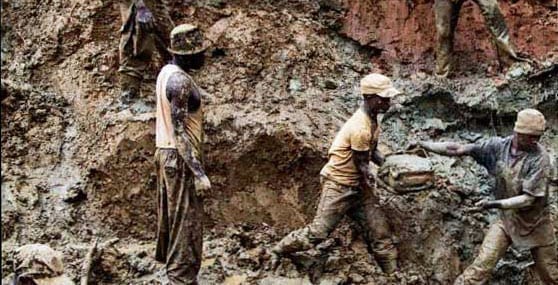

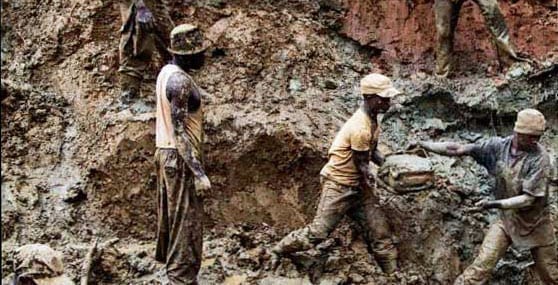

Workers in agriculture, fishing, manufacturing, domestic work and mining in the Global South are particularly vulnerable, while in advanced economies huge profits are generated from forced labor in supply chains.

“Our experience [in Norway] is that forced labor seems to appear together with social dumping and violations of the Working Environment Act (labor laws) and criminal activities,” Rasmussen explained.

Further ratifications

The ILO recently joined forces with the International Trade Union Confederation and the International Organization of Employers to the promote the ratification of the Protocol, primarily through the 50 for Freedom campaign.

By mobilizing public support, it is hoped that 50 countries will ratify the Forced Labor Protocol by 2018. It the ultimate aim is universal ratification of Convention 29—as eight countries, including the United States and China are yet to do so—and the Protocol by 2030.

While various countries have expressed support for the campaign, a number of African countries appear to be taking the lead. Mauritania has started the legislative process to ratify the Protocol and last month the Zambian president Edgar Lungu signalled his country’s commitment to eliminate modern slavery.

“My country will lead by example in taking the necessary steps required towards ratification of the Protocol,” he told delegates at a regional ILO conference on trafficking and forced labour in the Zambian capital of Lusaka.

Speaking at the same conference, Cosmas Mukuka, Secretary General of the Zambian Confederation of Trade Unions explain why the ratification is so important.

“Zambia continues to be the transit point for human trafficking in Africa meaning that enforcement of Convention 29 on forced labour remains a challenge and therefore calls for a regional strategy to effectively combat forced labour and human trafficking.”

Ahead of the International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, Urmila Bhoola, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, called on states, business and civil society to intensify the fight against modern slavery in supply chains.

“Modern slavery is particularly difficult to detect beyond the first tier of complicated supply chains of transnational businesses,” she said.

“However, these forms of slavery can be rooted out through a multi-stakeholder and multi-faceted approach ensuring that all business operations and relationships are based on human rights, that those responsible for supply chain-related human rights violations are held accountable and that the victims are guaranteed the right to effective judicial and non-judicial remedy and appropriate and timely assistance aimed at empowering them.”

Aug 26, 2015

Nurul Islam and three other men from his village in Burma’s Rakhine state believed the Rohingya brokers who promised to take them to Malaysia for jobs. Instead, the men were herded at gunpoint deep into a forest with 350 other migrant women, men and children, and told if they did not pay up to $2,300 each, they would be beaten and killed.

Beaten by his captors over four days, Nurul, 30, eventually called his uncle in Malaysia who agreed to pay the traffickers. But after he was released and contacted the police, he was taken to a government shelter where he again was deceived—a government official demanded $560 dollars for his release.

In a rare case of justice for survivors of human trafficking, the official, Anat Hayeemasae, a member of the Satun Provincial Administration Organization, was sentenced yesterday to more than 22 years in prison for human trafficking and ordered to pay Nurul $3,560.

Lawyers Working with HRDF Key to Prosecution

The success resulted from a more than year-long effort by lawyers working with the Human Rights and Development Foundation (HRDF), a Solidarity Center ally. They joined with the Rohingya Association of Thailand to investigate and file charges.

The result, says HRDF Secretary General Somchai Homlaor, “serves the objectives of HRDF’s Anti Human Trafficking in Labor Project to provide legal aid to a victim of human trafficking and to ensure the right of the victim of human trafficking to have access to justice process.”

Anat was found guilty of violating Thailand’s 2008 Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act and its 1979 Immigration Act, among other charges. He was among government officials from the Immigration Office who rescued Nural in March 2014 at Songkhla’s Hat Yai bus terminal.

Massive Human Trafficking in Thailand

Anat’s prosecution is especially noteworthy in an area where massive human trafficking occurs with impunity. In May, hundreds of bodies were found in 139 mass graves at suspected human trafficking camps on the border of Malaysia and Thailand. According to local news, Malaysian border patrol knew about the camps for 10 years, says Karuppiah Somasundram, education director for the Malaysian Trades Union Congress (MTUC). No arrests have been made.

Last month, the U.S. State Department retained Thailand on the bottom ranking of its annual Trafficking in Persons Report. The “Tier 3” ranking means Thailand is failing to comply with minimum standards to address human trafficking.

Migrant workers, primarily from Burma and Cambodia, work in slave-like conditions on Thai fishing boats, fueling the country’s $7 billion seafood export industry and making it the world’s third-largest exporter. Many migrant workers toil in forced labor and are held against their will on the boats where they are beaten and even killed. A Guardian series last year reported on the horrors endured by migrant workers who often are tricked by labor recruiters and sold into bondage. Estimates of migrant workers in Thailand range from 200,000 to 500,000.

A 2013 survey by the International Labor Organization (ILO) of nearly 600 workers in the Thai fishing industry found that almost none had a signed contract, and about 40 percent had wages cut without explanation. Children were also found on board. A 2009 U.N. report found that about six out of 10 migrant workers on Thai fishing boats reported seeing a co-worker killed. In another report, migrant workers say they were trafficked and forced to work for up to 20 hours per day with little or no pay. Many migrant workers in Thailand are in debt bondage.

Aug 5, 2015

Ishor, 24, migrated from Nepal to Malaysia last November to work for a company at Johor Bahru’s busy commercial shipping port. What he did not know before he arrived is that the job involved working 16-hour days and being physically abused and harassed by his employer. Like most migrant workers, Ishor likely paid a labor broker a large amount of money to secure the job.

“Agents usually give (migrant workers) a very beautiful picture about the conditions in which they are going to work,” says Karuppiah Somasundram, assistant secretary of education of the Malaysia Trades Union Congress (MTUC). “Usually (migrant workers) don’t get a clear picture about how the work is going to be in Malaysia.”

Unscrupulous private recruitment agencies, prevalent in the labor migration process, offer workers non-existent jobs; misrepresent working conditions and compensation; confiscate crucial documents, like workers’ passports and visas; and impose excessive and illegal fees, according to labor and migrant rights groups around the world.

Solidarity Center Conference Explores Labor Recruitment

Strategies for reforming the labor recruitment process is one of the key topics at the upcoming Solidarity Center conference on labor migration in Bogor, Indonesia. From August 10–12, more than 200 migrant worker rights experts will also discuss migrant worker access to justice, xenophobia and organizing migrant workers.

While Malaysia is a destination country for many migrants seeking work, Bangladesh sees more than 600,000 workers a year who leave for jobs, making it one of the largest countries of origin for migrant workers.

Bangladeshi workers who migrate “are suffering, they are crying, they are not getting food,” says Sumaiya Islam, director of the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA). “After two years, after three years, they are not getting their salary. After spending $1,000 (to labor recruiters), they are not getting paid.”

BOMSA holds “courtyard meetings” in villages around the country, helping women understand their rights before they migrate—including what they should demand of labor brokers and the wage and working conditions at the homes in Gulf and Asian countries where they will be employed as domestic workers. Simultaneously, BOMSA has been working to change national level policies to ensure that employers, not workers, pay recruitment fees.

The next step, Sumaiya says, is to educate employers in destination countries, “especially women, about the rights of domestic workers.”

Migrant Workers Need Jobs, Countries Need Workers

“Most Malaysians cannot take breakfast without migrants,” says Karuppiah. “You go to hotel, it’s a migrant; a car wash, it’s a migrant. At minimum, they work 12 hours or 14 hours a day. In Malaysia, (employers) give them one day rest day a month.”

On the other side of the migration spectrum, Sumaiya describes the factors pushing Bangladeshis far from their homes.

“I was in training center and I was talking with workers about why are you going,” she says. “Some say we need more money, more than 60 percent say we like to change our life because our husband is getting married again, some (husbands) are beating us, some (husbands) are drug addicts, some (husbands) are not giving us money for our family life. Most of them are saying they are supporting their family, Most of them cannot sign even their name, so they say ‘I have to go overseas so I can earn money.’”

Those working on behalf of migrant workers like Karuppiah and Sumaiya, believe that the majority of the world’s 247 million migrants who migrate for jobs will continue to do so. Their job is to make the process fair for workers, from their first contact with a labor broker to the day they return their families at home.

Karuppiah and Sumaiya will discuss their strategies next week at Labor Migration: Who Benefits? A Solidarity Center Global Conference on Worker Rights and Shared Prosperity.

Follow at Labor Migration: Who Benefits? at the Solidarity Center website and on Twitter @SolidarityCntr.

Jul 30, 2015

In Malaysia, up to 40 percent of workers are migrants from other countries. Over in Bangladesh, more than 600,000 workers migrate each year for jobs, and at least 5 million Bangladeshis currently work in other countries. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries on the Arabian Peninsula rely on migrant labor to fill more than 90 percent of private-sector jobs, with nearly 1.8 million migrants working in Qatar alone, 90 percent of the country’s population.

Most of the 247 million migrants in the world migrate for work. Although they may have starkly different backgrounds, when they migrate, they often share common experiences:

- They may be exploited by labor recruiters who charge them huge fees to get jobs, often requiring them to go into debt bondage, working with no salary so they can pay off their recruiter.

- They may be trafficked to engage in work they never signed up to do and then held captive by employers.

- They may be forced to live in unsanitary, unsafe conditions that may lack electricity and running water; they receive few or no days off and many are not paid.

- In the most extreme situations, they lose their lives on the job.

200+ Migrant Worker Experts Gather in Indonesia

How workers migrate and under what terms are critical questions for global economic, social and democratic development and, as we are reminded today, on World Day against Trafficking in Persons, millions of people also are trafficked each year, most often for labor exploitation.

Next month, more than 200 migrant worker and labor trafficking activists will meet in Bogor, Indonesia, to discuss strategies and solutions for the world’s growing migration and labor trafficking crises.

“Labor Migration: Who Benefits? A Solidarity Center Global Conference on Worker Rights & Shared Prosperity,” will bring together activists and leaders like Leo Tang, organizing secretary for the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU).

“Connecting people who are working for migrant workers is very important,” says Tang, who coordinates programs for migrant domestic workers across Hong Kong, Special Administrative Region of China. “These are particularly important years for the domestic worker movement and the migrant worker movement.”

Many who migrate abroad for jobs are domestic workers, the vast majority of whom are women. In fact, women make up some 50 percent of international migrants.

Labor Recruitment, Organizing and Migrant Access to Justice

Pablo de los Santos, president of the National Federation of Seller and Market Workers in the Dominican Republic, said through a translator that he wants to be able to “come out with examples from the conference to share with his community here to dispel myths about migrant workers,” and “would love to learn techniques on how to strengthen informal sector workers and how to better organize them.”

Co-hosted with one of our allies in Indonesia, Migrant Care, the conference is focused on labor recruitment reform, organizing workers, and access to justice for migrant workers. Among the many strategy-focused workshops are those on gender-based violence in the workplace; alternatives to private recruitment; and supply chains and migrant workers.

Follow Labor Migration: Who Benefits? at the Solidarity Center website and on Twitter @SolidarityCntr.

Jul 30, 2015

Global demand for the services of domestic workers, including household workers, caregivers and cooks, has been steadily rising in recent years. Yet as the International Labor Organization (ILO) shows in a new report on migrants from South Asia, domestic workers, especially women migrant workers, remain an “unrecognized and invisible” part of the labor force.

Further, the report states that “inadequate regulation and loopholes in existing emigration procedures have allowed unregistered agents to exploit potential migrants for monetary gain.” As a result, “emigrant workers are prone to different kinds of abuse and even to situations of forced labor.”

“Indispensable Yet Unprotected: Working Conditions of Indian Domestic Workers at Home and Abroad,” highlights forced labor and trafficking in South Asia and the Persian Gulf with the aim to “provide policy-makers and service providers with deeper insight into the nature of forced labor and trafficking” of domestic workers in and from India.

Among the workers the ILO surveyed, Jameela, 50, was enticed by a labor recruiter to migrate abroad from her home in Kerala in southwest India, for domestic work in one of the Persian Gulf states. The recruiter did not inform her about the working conditions she would face, and Jameela describes how her household employer not only forced her to work long hours without breaks but also withheld her wages, physically abused her and isolated her from other members of the household.

Jameela’s experiences are unfortunately all too common. The ILO reported that domestic workers throughout Arabian Gulf Coast countries suffered similar forms of abuse and many more. Women workers and migrant workers are particularly vulnerable to exploitation due to a lack of worker rights protections. Many are deceived about the nature of the work they will be required to do. Many also have their passports confiscated and their wages deducted or withheld by their employers. Workers are even threatened that they will be punished, sometimes with legal force, if they attempt to leave their abusive employers.

The ILO’s Domestic Workers Convention 189 serves as a framework for respecting migrant domestic worker rights at home and abroad. So far, 21 countries have ratified the convention.

The report demands that domestic workers in all countries who ratified ILO Declaration of Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work in 1998 must have their rights protected. This document outlines core labor standards which all signatories are expected to respect and promote, including the eradication of forced labor in all forms.

Last year, the ILO introduced the 2014 Protocol to the ILO’s Forced Labor Convention 29 and a Recommendation on Supplementary Measures for the Effective Suppression of Forced Labor. The organization is hoping to get at least 50 countries to sign the Forced Labor Protocol by 2018. Part of the ILO campaign includes spreading awareness of the abuses that migrant domestic workers face.

“Armed with this knowledge,” the ILO says, “action to combat trafficking in the region will become more effective, finally bringing an end to this unacceptable form of human exploitation.”