Jul 25, 2017

“Why does being low-wage and a migrant mean being sentenced to a lifetime of being separated from your family? It shouldn’t and doesn’t have to,” says Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau. Speaking at a United Nations meeting on migration today in New York, Bader-Blau contrasted the unchallenged right of capital to move freely across borders with the lack of rights and labor protections for migrant workers.

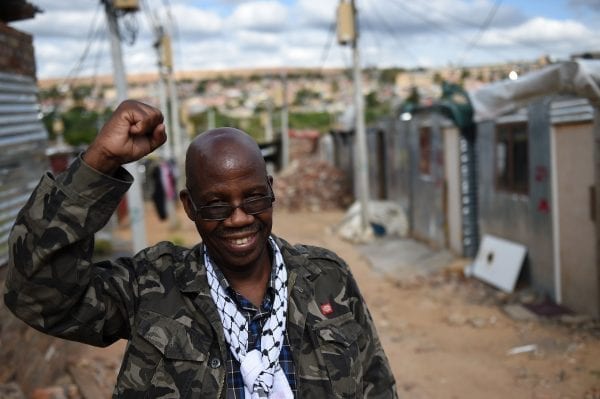

Being low-wage and a migrant should not mean being sentenced to a lifetime of being separated from your family–Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau Credit: Solidarity Center/Neha Misra

“We have not seen a commensurate expansion of the rights of people to go along with the incredible expansion of the rights of business, especially not for the migrant workforce. If we want to talk about the human rights of migrants, we really need to directly challenge those assumptions.”

Bader-Blau addressed the Fourth Thematic Event, “Contributions of Migrants and Diaspora to all Dimensions of Sustainable Development, including Remittances and Portability of Earned Benefits.” The July 23–25 meeting is among six thematic sessions held between April 2017 and November 2017 to gather substantive input and concrete recommendations to inform the development of the UN Global Compact on Migration.

Migrant Workers Should Be Free to Bargain with Employers

Neha Misa, Solidarity Center migration and human trafficking senior specialist, also spoke at the consultation, where she asked participants to “imagine if migrant workers could fully participate in the right to organize and collectively bargain.”

“We have seen time and time again how collective bargaining agreements provide migrant workers with the ability to earn a decent wage, and they may even be used to lower the costs of recruitment and provide migrant workers with more safe and secure ways to remit their earnings back home. Collective bargaining agreements also help to protect women migrant workers from gender-based violence and other forms of discrimination in the workplace.”

Misra, who also presented on behalf of the Women in Global Migration Network (WIMN), says “women in migration are not ‘vulnerable,’ in need of ‘rescue’—they are advocates for their rights and agents of change.” Current migration policies must be changed from being about ‘protecting women’ to ‘protecting women’s rights,’ she says.

The Solidarity Center is a member of WIMN and the Global Coalition on Migration, both of which took a strong role at the session.

Misra detailed a list of recommendations for inclusion in the UN Global Compact, including embedding core labor and human rights standards. (Read her full statement and recommendations here.)

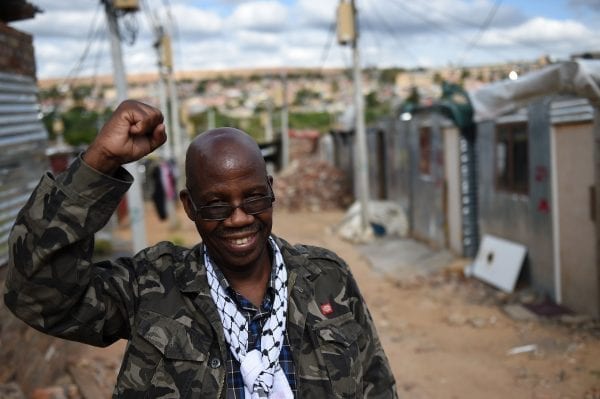

Many workers migrate for jobs because none exist in their home countries—Jonatan Monge Loría, chief coordinator of CI-Regional. Credit: Solidarity Center/Neha Misra

Addressing labor migration also means attending to the conditions that foster this phenomenon from origin countries, says Jonatan Monge Loría, chief coordinator of the Central American Regional Inter-Union Committee for the Defense of the Migrant Workers Rights (CI-Regional).

“Many dependent economies lack productive development policies that generate the quantity and quality of jobs that are required for decent work and livelihoods that sustain families,” says Loría. “It is no secret that poor development conditions and lack of job opportunities in origin countries are the trigger for this type of migration.”

Loría spoke on behalf of CI-Regional, a Solidarity Center partner, and the Trade Union Confederation of the Americas (TUCA/CSA) and the Trade Union Council for Technical Assistance. (See Loría’s full remarks in English and Spanish.)

‘Borders Are Not Exempt from Human Rights’

At the Third Thematic Event last month in Geneva, Asia Region Director Tim Ryan addressed the issue of governance of migration, saying “it is dangerous to think borders can be hermetically controlled, and borders are not exempt from human rights.

“Governments must move beyond an emphasis on temporary migration programs that restrict workers’ ability to exercise their rights—from freedom of association and voting rights to family unification—to regular migration programs that allow for visa portability, the ability to change employers, exercising political and social rights, freedom of movement, family unity and pathways to residency and citizenship in destination countries.” (Read Ryan’s full statement here.)

Jul 20, 2017

When Mwahamisi Josiah Makori arrived in Saudi Arabia in 2014 at the home of her employer, she was given 20 minutes to rest before beginning her duties as a domestic worker. Her employers held their noses when they greeted her and made her shower outside before allowing her in the house.

Her responsibilities involved cleaning two homes, including that of the employer’s mother-in-law. She was required to take care of the children, and when they spit on her, her employer told her not to complain. She was up all night caring for the baby and by 6 a.m., preparing the family’s breakfast.

She was given a torn, dirty mat to sleep on, and when she requested a new mat, her employer refused, telling her she was only there for work. In the middle of her tasks, she was required to stop and flush the toilet after a family member used the bathroom.

Makori was required to hold the baby throughout the day as she cooked, cleaned and cared for the other children. One afternoon, when she put the baby down to store groceries, the baby crawled to a cabinet. Alarmed, she called out. Her employer began beating her, saying she was making the baby nervous. They took her to the police authorities and told them she slept all day and refused to work.

She finally was able to convince the police of her plight, and an officer told her employer to pay her way home. The employer refused, but the employer’s mother-in-law paid her way to Kenya.

In Kenya, Makori had struggled to support her three children as a single mother. She was desperate for paid employment when her best friend introduced her to a labor broker who was traveling from village to village. Makori could not afford to pay her children’s school fees, and says she felt she had no choice but to leave the country for work.

After three months of nearly non-stop labor in Saudi Arabia, Makori returned to Kenya. Without pay.

Jan 25, 2017

Some 34 million Africans are migrants, and the majority are workers moving across borders to search for decent work—jobs that pay a living wage, offer safe working conditions and fair treatment.

Yet even as they often leave their families in search of jobs that will support them, many migrant workers find that employers seek to exploit them—refusing to pay their wages, forcing them to work long hours for little or no pay, and even physically abusing them.

Throughout the January 25-27 Solidarity Center Fair Labor Migration conference in Johannesburg, South Africa, migrant domestic workers, farm workers and mine workers share their struggles, but also their courage and hope as many join together to form unions and associations to improve their lives at work. Here are their stories.

Fauzia Muthoni Wanjiru left Kenya after a labor broker told her she would work in Qatar as a receptionist. Instead, she was taken to Saudi Arabia, where she was forced to work 18 hours a day as a domestic worker cleaning two homes a day. Her passport was taken, trapping her in the country. “When you go there, you are a slave to them,” she says.

Praxedes moved from Zimbabwe to South Africa so her children would live a better life than she had. “There is nothing for me there (in Zimbabwe), she says. “A lot of employers take advantage of that.” She has worked for more than five years as a domestic worker, and employers have refused to pay her overtime, and shortchanged her pay—even as her transportation costs take up a third of her wages. “My cellphone has to be off at all times. I have three kids. If anything happens to them, I will not know.”

Angela Mpofu migrated from Zimbabwe to support herself and her family as a domestic worker in South Africa. But like many migrant workers, she finds that she is treated poorly, as employers take advantage of her migrant status. Worse, says Mpofu, “the way (employers) treat us, it’s like we are not human beings. You’re nothing to them.”

As a migrant mine worker from Swaziland, Mduduzi Thabethe says he has fewer workplace rights than his South African co-workers. Although all mine workers pay the same amount into the health fund, migrant workers get inferior care and pensions are rare. “If you are a citizen of South Africa, you see you are building your country and you have something, but we have nothing.” His union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, is working to improve conditions for migrant workers.

When Joe Montisetse came to South Africa from Botswana to work in gold mines in the early 1980s, he saw a black pool of water deep in a mine that signified deadly methane. Yet after he brought up the issue to supervisors, they insisted he continue working, but Montisetse refused. Two co-workers were killed a few hours later when the methane exploded. Today, with the National Union of Mineworkers, Montisete, deputy president of the union, says workers are safer now. “We formed union as mine workers to defend against oppression and exploitiation,” says Montisetse.

In 2000, Chris Muwani migrated from Zimbabwe to South Africa, where he works on a tomato farm. If he does not fulfill his daily quota, he is not paid for the day. Migrant farm workers like Muwani are exposed to dangerous workplace conditions and without a union, cannot exercise their rights. “We use a chemical to spray grass but you don’t have rubber boots or a respirator but you are working with poison,” says Muwani. “If you protest about safety conditions, many people are fired.”

As a migrant farm worker from Mozambique, France Mnyike receives no health care coverage, even for workplace injuries. When Mnyike broke his leg at work, his employer did not provide medical aid and his leg remains fractured. Even if his workplace offered emergency care, says Mnyike, the employer would “deduct the cost from your salary.”

Jan 17, 2017

Edias was 12 years old when he traveled from Zimbabwe to South Africa to look for a job in agriculture. Now in his mid-twenties, he and other farm workers had been working 12 hour days, 7 days a week, and paid less than half the legal minimum wage when they asked the corporate farm owner for a raise last year.

Instead, they were assaulted and clubbed by a group of men led by the farm owner. Their homes—they lived on the farm—were burned. Edias described to Solidarity Center staff how he and four other workers were kidnapped, tortured and interrogated for hours before police arrived. (Find out how the Solidarity Center achieved justice for some of the migrant workers.)

Edias and his co-workers are among 34 million African migrants, the majority of whom are in search of decent work across borders. While an estimated 25 percent of African migrants are in Europe, the majority of migrants remain within the continent, often working in the most dangerous, unregulated jobs where they are paid little and have few rights.

Migration Conference to Address Trade Union Responses to Worker Exploitation

From January 25–27, the Solidarity Center will co-host a conference in Johannesburg, South Africa, that will bring together union leaders, migrant worker rights advocates and top international human rights officials from 22 countries and 57 organizations from around the globe to share strategies for empowering migrant workers throughout Africa.

“Achieving Fair Migration: Roles of African Trade Unions and Their Partners,” will explore best practices for asserting a worker rights agenda into national, regional and global migrant worker policies and examine tactics for strengthening cross-border and cross-regional cooperation among unions and other migrant rights organizations.

Maina Kiai, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of assembly and of association, will keynote the conference and discuss findings from the landmark report his office presented to the UN last fall. “Migrants have become a massive, disposable, low-wage workforce excluded from remedies or realistic opportunities to bargain collectively for improved wages and working conditions,” according to the report.

Vame Jele, who heads up the Swaziland Migrant Mineworkers Association (SWAMMIWA), will be among some 100 conference participants. SWAMMIWA advocates for migrant workers, especially for migrant miners, truck drivers, forestry workers, domestic workers and farm workers

“Beside networking and establishing partnership with unions, organizations and associations, we aim to learn and share knowledge especially on how we can advocate,” says Jele. He also seeks to raise awareness “and call for solidarity” around the issues of former miners and their families.

Migrant miners who contract silicosis and tuberculosis from working without safety equipment are sent back to their origin countries with no support for medical care. As a result, Jele says, many former miners are dying and their families are in poverty because they have lost their primary breadwinner. SWAMMIWA last month coordinated a policy dialogue around migration issues in Swaziland and advocates to harmonize policies and regulations in the South Africa Development Community (SADC) to abolish inhumane treatment of migrant workers and involve migrant workers in union bargaining.

‘African Unions Can Take a Lead in Shaping Labor Migration Policies’

The prevalence of informal jobs and the lack of recognition of migrant worker’s status “creates opportunities for exploitation and difficulties for unions to organize and represent migrant workers,” says Caroline Mugalla, executive secretary of the East African Trade Union Confederation (EATUC), who also will participate in the conference.

“And as women migrant workers become a larger component of migration, particular challenges arise as they tend to be relegated to the informal economy, face sexual harassment and gender-based violence in the workplace more often than men, and experience nationality and gender-based economic and social discrimination in the workplace.”

The “Fair Labor Migration” conference provides a forum for African trade unionists to coordinate strategies for reaching out to and empowering migrant workers, many of whom are part of the large and growing informal economy. Participants will discuss shaping a trade union agenda against xenophobia and racism, including strategies for tackling discrimination and xenophobia in unionized and non-unionized workplaces; the challenges of organizing and addressing migrant worker exploitation in the informal sector; increasing opportunities for migrant workers to exercise their rights and access justice; and labor protections.

“African trade unions can take a lead in helping shape the global governance of migration and promoting migrant worker rights at all levels of government,” says Solidarity Center Africa Regional Director Imani Countess.

“Government officials, businesses and corporate interests have sought to ‘manage’ the movement of migrants like everyday commodities through temporary migration programs and unregulated migration flows that benefit employers at the expense of workers.” The “Achieving Fair Migration” conference will provide a forum for exploring how to enhance African labor voices in global and regional migration governance policy.

The conference, co-sponsored by the African Regional Organization of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC-Africa), will include regional breakouts and opportunity for discussion around area-specific migration issues and hands-on strategic workshops with concrete action plans on union cross-border cooperation, organizing migrant workers and more.

Nov 9, 2016

When the employer of a migrant domestic worker takes her passport and refuses to return it if she seeks to leave, that is forced labor.

When a family works at a brick kiln to pay off a debt, their children prevented from attending school, that is forced labor.

When Uzbek teachers and doctors are mandated by the government to spend two months each fall picking cotton, that is forced labor.

Around the world, nearly 21 million people are forced laborers—11.4 million women and girls and 9.5 million men and boys. Ninety percent of forced labor takes place in the private economy, where it generates $150 billion in illegal profits per year.

Today, an International Labor Organization (ILO) Protocol on Forced Labor enters into force, requiring countries that ratify it to ensure the release, recovery and rehabilitation of people living in modern slavery. Adopted by the ILO in 2014, the protocol also protects workers from prosecution for any laws they were made to break while they were in forced labor.

The protocol and the accompanying recommendation supplement the 1930 ILO standard covering forced labor, Convention 29, and gives “new impetus to the global fight against all forms of forced labor, including trafficking in persons and slavery-like practices,” according to the ILO.

The protocol also bolsters the ILO’s 1957 Abolition of Forced Labor Convention 105. (Here’s a summary of the two forced labor conventions and the protocol.)

Protocol Would Compensate Those in Forced Labor

Among its provisions, the protocol:

- Guarantees forced laborers access to justice and compensation—even if they’re not legal residents of the country where they work.

- Protects individuals, especially migrant workers, from possible abusive and fraudulent practices during the labor recruitment and placement process.

- Requires employers to exercise “due diligence” to avoid modern slavery in their business practices or supply chains.

Nigeria was the first country to ratify the protocol and since then, eight more countries have done so. The ILO is urging people to join its 50 for Freedom campaign, which aims for 50 countries to ratify the protocol by 2018 to be truly effective.

Join Campaign Urging Countries to Pass Protocol!

Send a message to your labor minister urging passage of the protocol here. The action is hosted by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), which is a member of the 50 for Freedom coalition, as is the Solidarity Center.

You also can sign up to get more information on the campaign and spread the word to your networks and on social media with the hashtag #50FF.

Additional 50 for Freedom materials include: