Jun 26, 2019

“Defunding the programs that protect vulnerable people’s human rights and meet their basic needs is a nonsensical approach to combating trafficking,” said Shawna Bader-Blau, the executive director of the Solidarity Center, a global workers rights organization that operates in 60 countries and has been affected by the Trump administration’s decisions.

Mar 28, 2019

In Gulf Cooperation Council countries—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates—amnesties for workers in irregular status are frequently declared, indicating that irregularity is a common and recurring phenomenon within the governing kefala, or work-sponsorship, system. However, even if implemented perfectly, amnesty is a temporary fix, and effective solutions to reduce the population of undocumented migrant workers requires adherence to labor rights principles, according to a new report by the Solidarity Center and Migrant-Rights.org.

The GCC countries are characterized by a majority migrant workforce, tied to their employer-sponsors through kefala. However, for workers whose sponsors fail to renew work visas or for workers who are duped by fake jobs in the recruitment process or who land in untenable and abusive situations, workers “face a series of narrow, unenviable choices and are systematically denied freedoms enshrined in international human rights law,” says the report, Faulty Fixes: A Review of Recent Amnesties in the Gulf and Recommendations for Improvement.

In fact, the report adds: “Migrant workers who are unable to legally leave their job, or leave the country in some cases, are vulnerable to a range of abuses including occupational safety and health violations and gender-based violence as well as non-payment of wages and other forms of forced labor.”

The report has a variety of recommendations for countries of origin and Gulf nations to improve working conditions for migrant workers and to minimize factors that push them into irregular status. Among them: planning and communicating about an amnesty with migrant worker embassies and communities; investigate absent or abusive sponsors; and informing workers about their rights.

See the full report in English and Arabic.

Jul 27, 2018

Aldaberdi Karimov, 42, who lives in a remote Kyrgyzstan village in the Batken region, did not want to migrate from his country to find work to support his family, including his daughter, Ak Maral, now 5 years old.

But like many in Kyrgyzstan, where remittances from workers abroad make up more than 25 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, Karimov faced the heart-wrenching decision to leave his family to find employment. In fact, so few good jobs are available in the country, especially for workers in rural areas, only 24 percent of Kyrgyz workers are employed in the formal economy.

Aldaberdi Karimov escaped from forced labor and is back in his Kyrgyz village with his family, including his daughter, Ak Maral. Credit: Solidarity Center

And when he left his village, Karimov had no idea he would be a target of force labor and human trafficking. Globally, more than 21 million people are in forced labor, according to the International Labor Organization, which on July 30 marks World Day against Trafficking in Persons.

Forced to Live with Cows in the Barn

Karimov first sought jobs in Russia and then migrated to Kazakhstan, where he worked as a market vendor in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city. Karimov thought he would fare better in Kazakhstan because, like Kyrgyzstan, it is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union.

Between 100,000 to 150,000 Kyrgyz were registered in Kazakhstan at the end of 2017, figures that do not reflect many who are not registered, according to a new report by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). Most work without written contracts or on contracts that do not adequately protect their rights. Their passports typically are confiscated by employers, making it difficult for them to leave abusive jobs, and they have no access to labor protections like safe working conditions and paid leave.

Karimov could not afford the permit needed to sell goods legally in Kazakhstan—costing between $1,500 and $2,000, a permit is the equivalent of a year’s wage. Through an intermediary, he and his brother, Giyazidin, were led to a job on a Kazakh farm in June 2016 tending 100 cows and 2,000 sheep. The farmer said he would pay them 40,000 tenge ($117) each per month.

“The employer promised to pay us not every month, but once every three or four months,” Karimov says. “After three months, we asked for an advance and our employer became very angry and said that the cows and sheep are very thin, so he is not going to pay yet.”

By October, they each had been paid only $100 for six months’ work. Frost and cold rains began and when the brothers asked to be housed in a warmer environment than their small thatched hut in the field, the employer told them to live with the cows and rams in the barn.

Tens of Thousands of Workers in Forced Labor in Kazakhstan

Essentially trapped in forced labor, the brothers made their escape after Giyazidin became so ill that the farmer took him to the hospital. Tens of thousands of workers are estimated to be victims of forced labor in Kazakhstan, with migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan forced to labor in agriculture, construction and the extraction industry.

Like many migrant workers, neither Karimov nor his brother reported their abuse to the police because they did not trust them. In fact, officers of law enforcement agencies often are the link between migrant workers and “buyers” of labor, according to the FIDH report.

Karimov says lack of a labor contract and no police protection left him and his brother vulnerable to human traffickers and inhumane working conditions. Around the world, most migrant workers are denied the right to form unions and bargain with their employer—a fundamental freedom that enables abuse and exploitation. “The lack of labor agreements entails forced labor and even slavery,” says Aina Shormanbayeva, president of the Legal Initiative, a Kazakhstan-based public foundation.

Now back in his village, Karimov says migrating for jobs is now out of the question, even as he searches for work, still seeking wages that will enable him to support his family

Jul 19, 2018

Workers who migrate from Kyrgyzstan to Kazakhstan for jobs often do not receive their wages, are forced to work in unsafe and abusive conditions and even are kidnapped and held against their will in forced labor, according to a new report.

“Invisible and Exploited in Kazakhstan” also found that children are forced to labor, with young girls between ages 12 and 17 working as nannies, and boys working in markets and on farms. The report is based on the findings of a series of missions by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and its partners from September to November 2017 in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. The Solidarity Center contributed extensively to the report.

“The right to freedom of association is a core principle of human rights and worker rights, including when workers are migrating for jobs,” says Lola Abdukadyrova, Solidarity Center program coordinator. Abdukadyrova spoke yesterday at a press conference in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, where the report was released.

Bedroom of five migrant workers in the basement of a construction site in Kazakhstan, November 2017. Credit: FIDH

Between 100,000 to 150,000 Kyrgyz were registered in Kazakhstan at the end of 2017, figures that do not reflect many who are not registered. Most work without written contracts or on contracts that do not adequately protect their rights. Their passports typically are confiscated, making it difficult for them to leave abusive employers, and they have no access to labor protections like safe working conditions and paid leave.

“The lack of labor agreements entails forced labor and even slavery,” says Aina Shormanbayeva, speaking at the press conference, which drew nearly two dozen reporters. Shormanbayeva is president of the Legal Initiative, a Kazakhstan-based public foundation.

Some 81,600 workers were victims of forced labor in Kazakhstan in 2016, according to estimates by the nonprofit Walk Free Foundation, with migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan forced to labor in agriculture, construction and the extraction industry.

Women Migrant Workers Targets of Gender-Based Violence

While some one-third of all migrants were women two to three years ago, the report finds women now comprise half of migrant workers. Women are especially vulnerable, facing gender-based violence in agricultural fields and in employers’ homes when working as domestic workers. They may lack medical care while pregnant and often are fired when employers learn of their pregnancy.

Says one woman migrant worker: “I work as a janitor from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., and when there are banquets, until 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. Lunch breaks are 30 minutes maximum. There are no days off. I work every day. Some people can’t prove anything when they don’t get paid because nothing is documented. One woman worked at a car wash, they told her they didn’t have money and so they didn’t pay her. This happens to many people.”

Solidarity Center’s Lola Abdukadyrova, (second from left), discussed the plight of migrant workers in Kazakhstan during a press conference in Bishkek. Credit: Solidarity Center

The report finds migrant workers are not aware of their rights on the job, and they rarely appeal for protection of their rights when their employers perform illegal actions. They also do not believe police are able to protect their rights. In many cases, officers of law enforcement agencies are the link between migrant workers and buyers.

“Kazakhstan has not taken effective measures to prevent, investigate and prosecute persons involved in providing illegal intermediary services, and has not ensured effective legal protection for the victims,” the report states. Kazakh authorities argue that it is not their responsibility to protect migrant workers, and that protection of migrant workers is the responsibility of Akims (heads of regional or local authorities).

Kazakhstan was recently rated one of the 10 worst countries for workers by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). Union leader Larisa Kharkova was sentenced in 2017 to four years of restrictions on her freedom of movement, a ban on holding public office for five years and 100 hours of forced labor on false charges of embezzlement. Kharkova led the Confederation of Independent Trade Unions of Kazakhstan, which was ordered closed by a court ruling. Independent trade unions in Kazakhstan face ongoing attacks on freedom of association and basic trade union rights.

Over the past five years, the Solidarity Center in Kyrgyzstan has worked extensively to advance migrant worker rights, including holding awareness-raising campaigns for potential migrants and their families; supporting a hotline on labor migration issues; and assisting unions in protecting and promoting migrants’ worker rights.

Jun 28, 2018

Myanmar (Burma) and Turkmenistan do not meet minimum standards to address human trafficking and are making no attempts to do so, according to the 2018 U.S. State Department’s 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report released today. The report, which ranks countries based on their government’s efforts to comply with minimum U.S. Trafficking Victims and Protection Act (TVPA) standards, also boosted Uzbekistan from the bottom ranking to the Tier 2 Watch List.

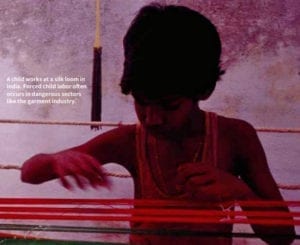

A child works at a silk loom in India. Credit: TIP report

The governments of both Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan annually force public employees and others to labor in the cotton fields. Although Uzbekistan recently has taken steps to end forced labor, the Uzbek government’s upgrade to the Tier 2 Watch List “is premature due to its persistence on a large scale—at least a third of a million people—in the last harvest,” says Bennett Freeman, former deputy assistant secretary of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor and co-founder of the Cotton Campaign, a broad coalition working to end forced labor in the cotton fields.

Myanmar was downgraded this year from the Tier 2 Watch List, which requires, in part, that countries not fully meeting the TVPA’s minimum standards make significant efforts to do so.

The report also downgrades Malaysia from Tier 2 to the Tier 2 Watch List, addressing the country’s controversial upgrading in 2016 from the lowest ranking. Solidarity Center allies have documented extensive forced labor conditions in Malaysia. The Kyrgyz Republic and South Africa also were downgraded from Tier 2 to the Tier 2 Watch List, which includes countries like Bangladesh, Guatemala, Haiti, Iraq, Liberia, Nicaragua and Nigeria.

Thailand was upgraded from the Tier 2 Watch List to Tier 2.

Profits from forced labor account for $150 billion in illegal profits per year, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

The TVPA report organizes countries into tiers based on trafficking records: Tier 1 for nations that meet minimum U.S. standards; Tier 2 for those making significant efforts to meet those standards; Tier 2 “Watch List” for those that deserve special scrutiny; and Tier 3 for countries that are not making significant efforts.

The Trafficking in Persons report, which has been issued annually for 18 years, covers 190 countries and is required by the 2000 TVPA law.