May 16, 2018

Some 40 domestic workers from 17 countries across North and South America and the Caribbean shared organizing tactics, hammered out resolutions and participated in Solidarity Center training on gender-based violence at work at a recent conference in São Paulo, Brazil.

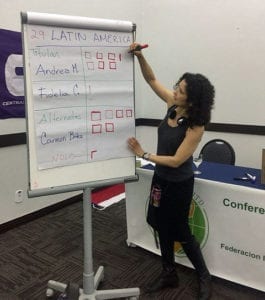

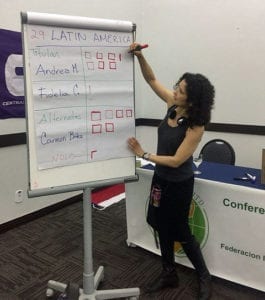

A Solidarity Center gender equality training was part of the domestic workers’ conference. Credit: IDWF

The conference is one of a series of regional planning meetings domestic workers around the world are holding in advance of the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) congress November 16–18 in South Africa. Domestic workers from all regions will bring recommendations to the IDWF Congress. Latin American domestic workers voted to recommend the IDWF adopt resolutions involving safety and health, strengthening leadership of Afro-descendent domestic workers where they are a majority and supporting LGBT domestic workers who face double discrimination on the job.

Delegates also nominated new leadership for the region, Andrea Morales from Nicaragua and Carmen Britez of Argentina, both former domestic workers.

In one of the most powerful moments of the conference, migrant domestic workers and Afro-descendent domestic workers shared their strategies during a panel on racial equality and, in the process, “restored dignity back to themselves and to the work they do,” says Adriana Paz, IDWF Latin America regional coordinator.

“Most domestic workers labor in modern slavery conditions without being paid but instead just provided with board and room—just like in slavery times,” says Paz, who participated in the conference. “Added to this lack of rights and freedoms, Afro-descendant domestic workers face the structural violence inflicted on them because of the intersection of their race, class and gender.”

In Brazil, 70 percent of domestic workers are Afro-descendent as are a majority of domestic workers in Colombia, who also are often internal migrants, moving from rural areas to large cities for employment.

Steps to Ensure Brazil Enforces Domestic Worker Standard

Credit: IDWF

Brazil’s ratification of International Labor Organization Convention (ILO) 189 on domestic workers’ rights earlier this year led to discussions about how Brazilian domestic workers could ensure the government is in compliance with the convention. Domestic workers from countries that have ratified Convention 189 say the first step is to push for creation of employer organizations so domestic workers have a collective employer with whom to negotiate contracts.

Enforcement of domestic workers’ rights is difficult in Brazil because the constitution does not allow authorities to “inspect” private homes, a challenge Argentine domestic workers say they have addressed by sending out mobile vans in neighborhoods where they find employers with domestic workers. From the vans, union staff and labor ministry representatives discuss with employers how to formalize workers and have paperwork ready for employers and specific materials for domestic workers as well.

Conference participants also took part in a Solidarity Center workshop on the upcoming International Labor Conference (ILC), where representatives from labor, employers and governments will negotiate a draft convention addressing gender-based violence at work. Five domestic workers from Latin America will attend the May 28–June 8 ILC, all of whom were active in the international campaign for passage of Convention 189 in 2011.

Domestic workers in the Africa, Asia and European regions held regional conferences earlier this year.

May 15, 2018

Uzbek union activist Fakhriddin Tillayev, in prison on a 10-year sentence and subjected to torture for attempting to organize an independent union for day laborers, was released over the weekend.

Tillayev’s release was among the results sought by a Cotton Campaign delegation, now in Tashkent, Uzbekistan’s capital, for unprecedented meetings with government officials, civil society advocates and human rights monitors to discuss the eradication of forced labor. During last fall’s harvest, the Uzbek government forced 336,000 people—including teachers, doctors and students—to work in the country’s cotton fields, picking a crop that generates nearly a quarter of the nation’s GDP, according to an International Labor Organization (ILO) survey. The Cotton Campaign believes the number of those forced to labor is higher.

Tillayev’s release “is a very positive step by the government,” says Solidarity Center Europe and Central Asia Regional Program Director Rudy Porter, who met with Tillayev after his release. Human Rights Watch, the Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights, Cotton Campaign staff and the Solidarity Center all followed Tillayev’s case closely since his sentencing in 2014 and raised demands for his release in each meeting with the government.

Tillayev and his fellow activist, Nuriddin Jumaniyazov, were falsely accused of human trafficking, tortured and convicted in proceedings that violated fair trial standards. Jumaniyazov, who was sentenced to six years on the same charges as Tillayev, died in prison of complications related to diabetes in December 2016, information that was not made public until June 2017.

Tillayev said he and Jumaniyazov were arrested after they collected membership applications for an independent union from many people looking for day labor at eight markets in Tashkent.

“They had no other work, they needed protection, they needed their own union. The Administrative Court fined each of us 7 million Soum [$875] because we organized an independent union. They banned the independent union. And then they came up with a criminal offense to put us away for good.”

Seeking a Formal Plan to Dismantle State-Sponsored Forced Labor

Cotton Campaign coalition representatives are in Uzbekistan seeking legal and policy reforms to end the mobilization of education and healthcare workers to harvest cotton. They also are calling for an to end the practice of forcing those who refuse to go to the fields to pay for replacement workers.

The delegation seeks a formal plan to dismantle the forced labor system, and an accountability mechanism that allows for secure complaints and legal actions against officials who mobilize citizens. The Cotton Campaign delegation does not include forced labor monitors and will not assess Uzbekistan’s progress toward eliminating forced and child labor in cotton production.

Steve Swerdlow from Human Rights Watch says “one of the biggest developments in Uzbekistan has been the release of political prisoners.” Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

The Cotton Campaign sees these meetings as among “recent encouraging signs that the Uzbek government is willing to talk about the subject of forced labor.” Last week, the government released journalists imprisoned on political grounds.

Noting that Uzbekistan has released 28 political prisoners in the past 20 months, Steve Swerdlow, Human Rights Watch Central Asia researcher, says “one of the biggest developments in Uzbekistan has been the release of political prisoners.” Swerdlow spoke May 14 as part of an Uzbekistan-sponsored press conference in Washington, D.C., to discuss its progress on human rights and prospects for improvement.

Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev acknowledged forced labor in cotton production in a speech at the United Nations in September, the first time a high-ranking Uzbek government official had done so in a public forum. Mirziyoyev again repudiated forced labor in April when he referenced teachers being mobilized for street cleaning and other “public works.” With its partners in the Cotton Campaign, the Solidarity Center advocates for the complete eradication of forced labor and forced child labor in Uzbekistan.

Mar 28, 2018

After years of hardship for workers due to illegal corporate employment practices and a lack of recognition of their rights, a Colombian union of subcontracted palm workers won direct employment contracts for 730 of its members. Successful negotiations followed a 20-day strike earlier this year that brought management of the largest palm oil producer in the country, Indupalma, to the table.

Jorge Castillo, UGTTA president, conducts the ratification vote for the accord. Credit: Digna Palma

Last year, the palm oil workers formed the General Union of Third-Party Agribusiness Workers (UGTTA). Despite the region’s history of threats and violence against workers who form unions, the UGTTA has grown from 248 to some 1,010 members. The union reports four members received death threats in 2018.

The Ministry of Labor determined in 2016 that Indupalma illegally subcontracted the majority of its 1,200-person workforce. The company imposed a model of phony cooperatives, essentially classifying workers as owners without labor rights or decent working conditions. As subcontracted workers, the palm oil workers had no rights under Colombia’s labor laws, including the minimum wage, freedom of association and the right to negotiate working conditions. They walked off the job outside San Alberto January 25 to demand formal work status.

Beginning in 2017, a broad coalition of palm workers’ unions known as the Worker Pact (Pacto Obrero) provided critical organizing and advocacy support, which, in addition to a sound legal strategy and international pressure, prompted the Ministry of Labor to intervene and facilitate a negotiation that led to a formalization accord between UGTTA and Indupalma.

The accord finalized on March 15 calls for the creation of two new affiliate companies (with sufficient capital and investment to meet legal obligations to the workforce) that will directly employ workers from two Indupalma work sites in the Magdalena Medio region. The accord also explicitly abolishes the use of the cooperative model. This process is to be completed by August 2018.

The union unanimously ratified the accord and has expressed deep gratitude for the solidarity it has received. The 730 members who will become direct employees will enjoy the full protection of the labor law and will be entitled to the minimum wage, social security benefits, health and safety standards, and organizing and collective bargaining rights. This win has lifted the entire San Alberto community, as families anticipate that improved wages and job security will provide additional resources that benefit their households and help educate their children.

The Solidarity Center will continue to work alongside the UGTTA and Pacto Obrero to monitor enforcement of the accord.

Mar 23, 2018

Two union activists were murdered in Guatemala and one in Honduras, while dozens of others were targets of violence—including threats of murder, kidnapping and stalking—over the past year, according to two reports released this week.

In Guatemala, “where the unionization rate is less than 1 percent, intolerance and violence against workers highlights, precisely, the mechanisms of terror to limit and, in many cases, to ignore those rights on the part of employers,” according to the Annual Report on Anti-Union Violence. The report, by the Network of Labor Rights Defenders of Guatemala (REDLG), found two more instances of violence in this reporting year (February 2017–February 2018) than in the previous period.

Since 2004, 87 union leaders and activists have been killed in Guatemala, one of the most dangerous nations in the world for union rights activists.

In Honduras, many of those targeted in the 39 documented instances of violence were organizing unions or seeking collective bargaining agreements in the agro-industrial palm oil sector in Colón, according to the report, “Freedom of Association and Democracy” by the Anti-Union Violence Network. Both networks are Solidarity Center partners. (The report is available in English, including an Executive Summary, and Spanish.)

Honduran Union Activist Targeted after Report Released

Isela Juárez is among Honduran union activists targeted with death threats. Credit: Anti-Union Violence Network of Honduras

Two days after the report on Honduras was released this week, union leader Isela Juárez, who has received death threats for her worker rights activism, was followed in a high-speed chase by two men on motorcycles before she took refuge inside the San Pedro Sula City Hall. Juárez, president of the Union of Workers of Municipal, Common and Related Services, (SITRASEMCA), also had been honored for her defense of human rights over the weekend.

The report on Honduras finds that 51 percent of the alleged perpetrators are public officials, including the military police, along with municipal authorities who harassed, coerced and fired nine workers to prevent them from forming unions.

Some 100 unionists and other members of civil society took part in the report’s launch, and several people violently targeted for their activism described their experiences. Since the network in Honduras began documenting cases of anti-union violence in 2015, 69 union activists have been targeted with violence, including seven who were murdered.

The report on Honduras also highlights a correlation between increased violence and the growing role of women in union leadership, and documents cases of unionists attacked during the post-election violence as they sought democracy.

In both countries, poverty and extreme poverty is high, with the World Bank estimating that in 2016, 65 of every 100 Hondurans lived in poverty, and 43 of every 100 in extreme poverty. In Guatemala, despite a growing economy, poverty rose to 59.3 percent in 2014.

The U.S. government has declined to consider anti-union violence in Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) complaints filed by the AFL-CIO and Guatemala and Honduran trade unions.

Feb 2, 2018

Truckloads of children were sent to pick cotton during the Turkmenistan fall harvest, according to a new report by the Alternative Turkmenistan News (ATN), an independent media and human rights organization. The children, along with tens of thousands of civil servants, including pregnant teachers, were forced to pick cotton for weeks in a government-led mass mobilization of forced labor that began August 15 and lasted through December.

In a secret order, “the local education department even sent a memo to the schools in [Ruhabat and Baharly] districts to organize the mobilization of children for the harvest during the fall break,” according to the report. ATN sources also reported a massive use of forced and child labor in several districts of Dashoguz, Lebap and Mary provinces.

“The cotton harvest feels like serfdom because you go to work in a rich man’s land”—public utility worker. Credit: ATN

A teacher told ATN that pregnant teachers showed their principal a doctor’s certificate to be excused from field work, but the principal forced them to go—and ramped up their cotton collection quota from 110 pounds a day to 132 pounds. Another source reports officials at institutions, like local schools, financially benefit from the use of forced labor.

A public utility service worker in Dashoguz province told ATN that if workers refused to pick cotton, they will lose their job. “The boss will happily hire someone else for your job and even get a bribe for it. Unemployment is so high in Dashoguz that bosses won’t have hard time finding your replacement.”

Although most of the cotton harvest takes place on government-run land, scores of cotton pickers also say they were forced to work in either private fields or lands leased long-term by wealthy landlords or high government officials. “The cotton harvest feels like serfdom because you go to work in a rich man’s land,” says the public utility worker.

Human Rights Abuses Rampant

The Turkmen government “tightly controls all aspects of public life and systematically denies freedoms of association, expression and religion,” according to Human Rights Watch. Gaspar Matalaev, an activist who provided photographs documenting child labor during Turkmenistan’s cotton harvest, was arrested in 2016 and is serving a three-year prison sentence on trumped-up fraud charges. He has reportedly been subjected to torture by electric current to force him to confess to false charges of minor fraud.

Turkmenistan remained in the lowest ranking in the U.S. State Department’s 2017 Trafficking in Persons Report, meaning the government does not comply with minimum U.S. Trafficking Victims and Protection Act (TVPA) standards and is not making significant efforts to become compliant.

The Turkmenistan government “continued to use the forced labor of reportedly tens of thousands of its adult citizens in the harvest during the reporting period,” according to the report. “It actively dissuaded monitoring of the harvest by independent observers through harassment, detention, penalization, and, in some cases, physical abuse.”

In neighboring Uzbekistan, where 1 million public employees are forced to pick cotton each fall harvest, children also were forced into the fields this past fall. The government had stopped the practice in recent years following campaigns by international human rights organizations, low rankings in the US Trafficking in Persons Report and threats by the World Bank to curtail funding.