Jun 17, 2015

Hundreds of thousands of workers in the Dominican Republic without official identification papers have until today to register with the government or face deportation. The move—condemned widely as a violation of human rights—could leave as many as 120,000 Dominican-born and -raised women and men stateless, their future and their ability to earn a living jeopardized. If they cannot regularize their status, their next stop, as soon as tomorrow, may be the Haitian border.

Dominicans of Haitian descent have long faced exploitation and discrimination and experienced trouble obtaining official documentation, despite spending their entire lives in the country. Many speak only Spanish and have few, if any, ties to neighboring Haiti. However, a controversial 2013 Constitutional Court decision ruled that that individuals who were unable to prove their parents’ regular migration status could be retroactively stripped of their Dominican citizenship. While a later presidential decree recognized the citizenship of roughly 68,000 people, an additional 130,000 Dominican natives who never had documents were forced to prove birth in the Dominican Republic country to apply for Haitian citizenship and, with Haitian documents, apply for regularization in the country of their birth. Only about 10,000 of these people applied under the plan.

A 2014 report by the Solidarity Center and AFL-CIO, “Discrimination and Denationalization in the Dominican Republic,” called the ruling an “egregious abuse of fundamental human rights and a clear violation of international law.” Indeed, said the report, the actions by Dominican officials leading up to and following the ruling “demonstrate the depths of entrenched discrimination.”

In September 2014, Dominican unions and human rights groups raised concerns that the registration process was fraught with irregularities, unnecessary hurdles and bureaucracy. They said some local agencies were charging exorbitant fees for documents that were supposed to be provided for free and which applicants needed to demonstrate long-term residence. They said some workers had waited months for notification of the results of their applications, even though the law stipulates a response within 45 days.

Said Alexis Rosalie, spokeswoman for the National Coordinator for Immigration Justice and Human Rights and an organizer for the National Federation of Workers in Construction and Building Materials (FENTICOMMC), at the time: “We have proof there are people who meet all the basic requirements of the National Plan for Regularization of Foreigners (PNRE), and each time they go back to the offices, they are always told they are lacking one document or another.”

According to a report today by The Guardian newspaper, only 300 people applying for official identification received it.

Shawna Bader-Blau, executive director of the Solidarity Center, said: “We are astounded by this deliberate creation of a stateless underclass. Tens of thousands of people who live on the margins today and could be separated from their loved ones, their social networks, their jobs—all that is keeping them barely afloat—tomorrow.”

In past weeks, representatives of the Network of Support to Migrant Workers of the National Confederation of United Trade Unions (CNUS) and the Migrant Justice Movement, a grouping of unions and migrant organizations formed at a 2014 advocacy training organized by the Solidarity Center, held a series of press interviews calling for an extension to the regularization plan. Other groups, including Amnesty International, are calling on the government to respect international law and standards, and to “establish adequate mechanisms to avoid the expulsion of Dominican-born people who were deprived of their Dominican nationality in September 2013, including a specific screening process targeting Dominicans of Haitian descent.”

Jun 17, 2015

Nobel Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi led a rally against child labor at the Lincoln Memorial. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeff C. Wheeler

Saying that “168 million children are producing wealth, producing clothes, producing shoes, the things that you and I use,” child rights advocate Kailash Satyarthi told a crowd gathered yesterday at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.: “We are here to say that we denounce all forms of child slavery, of human slavery.”

On the 157th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech on slavery, Satyarthi, winner of the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize, spoke of the urgency with which child slavery must be eradicated. The Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation organized the meet-up for childhood freedom June 16, days after the global community marked World Day Against Child Labor.

Many of the 168 million child workers around the world are forced into slavery or prostitution or serve as child soldiers. Most, Satyarthi said, work in hazardous and even life-threatening conditions. While this number is down from 246 million in the 1990s, Satyarthi said there is still a long way to go.

“Every child should be free to be a child,” he declared. “Every child should be free to love, free to play, free to go to school, free to have a dream.”

Satyarthi called for organizations to work together to end child labor. “I have worked with civil society, I have worked with trade unions, I have worked with teachers’ organizations,” he said. He explained how such organizations are vital to promoting human rights, especially for children. “Companies like child labor because it is cheap, because children can be easily exploited,” he said. “Children cannot form unions, they cannot go to the polls.”

Satyarthi recalled the visions of freedom activists who came before him, including not only Abraham Lincoln but also Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela. “I feel pain,” Satyarthi said. “I am angry that we have not been able to pay the real tribute to these men by eradicating slavery.”

He also insisted that child labor and poverty could not be vanquished without serious investment in education. He lamented poorly financed school systems in some developing countries, where funds for education amount to less than three percent of gross domestic product. Children’s education also receives less than one percent of humanitarian aid worldwide, Satyarthi reported.

“We cannot have a just, dignified world without education,” he declared. “My children in the world cannot wait. Freedom must happen now.”

Jun 16, 2015

Labor and human rights groups are applauding a statement by United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon who said during a recent visit to Uzbekistan that more must be done now to address “the mobilization of teachers, doctors and others in cotton harvesting, and prevent the maltreatment of prisoners.”

On June 5, dozens of labor and human rights organizations, including the Solidarity Center, sent a letter to Ban Ki-moon urging him to raise the issue of forced labor in which the government requires teachers, doctors and others to pick cotton each fall.

During each fall harvest, Uzbekistan’s government forces teachers, doctors and other health care professionals to pick cotton. At least 17 people died and numerous others were injured during last year’s harvest. Workers were forced to toil long hours picking cotton in unsafe and unhealthy working conditions that often included no access to clean drinking water. Students receive little or no education and medical care is inaccessible for weeks until the harvest is completed.

In the letter, the organizations called the Uzbekistan cotton harvest “one of the largest state-orchestrated systems of forced labor in the world for decades,” and listed six steps the Uzbekistan government should take, including permitting human rights organizations and journalists to investigate and report conditions in the cotton sector without retaliation.

Earlier this month, human rights activists Elena Urlaeva says she was arrested and assaulted by police as she sought to document the Uzebek government’s forced mobilization of teachers and doctors for the spring cotton harvest.

Noting that Uzbekistan has enacted legislation to protect the rule of law, Secretary-General Ban noted, “But laws on the books should be made real in the lives of people,” indicating the government has not properly implemented its own legislative framework.

Jun 16, 2015

On a trip to Kuwait two years ago, Nisha Varia from Human Rights Watch visited a hospital where two rooms were filled with injured domestic workers who had tried to escape from their employers’ homes. Trapped in abusive situations, the women jumped from windows or were beaten by employers as they sought to leave.

The experience for domestic workers in Middle Eastern Gulf states, and in many countries around the world, has not significantly improved since then, said Varia and others at a recent panel in Washington, D.C., “Migrant Workers in the Gulf States: Transnational Policy Responses to Protect Labor Rights.”

In the Gulf, “employers feel they have bought domestic workers because they paid the recruitment fee,” Varia said. The situation is exacerbated in Gulf countries by the kefala system, which ties employment of foreign workers to their employers, and makes it illegal for workers to get another job in the country. Employers also typically take the passports of domestic workers, who toil unseen from the public and are especially vulnerable to abuse.

June 16, International Domestic Workers Day, marks the fourth anniversary of the adoption of the United Nations Convention 189 on Domestic Workers, a landmark standard championed by unions, civil society groups and human rights organizations worldwide. Its passage signaled the global community’s recognition that the 53 million workers who labor in households, often in isolation and at risk of exploitation and abuse, deserve full protection of labor laws.

The historic action indicated the recognition that domestic workers, 83 percent of whom are women, perform work—and that entails rights equal to all other wage earners. Eighteen countries have ratified the Convention since its passage. (ILO resources for and information on domestic workers here.)

The panel, which encompassed broader issues of labor migration, highlighted the overlap between domestic workers and migrant workers. The Solidarity Center works with domestic workers in countries such as Dominican Republic, where most domestic workers are from Haiti and in Jordan, where domestic workers have migrated for work from the Philippines, Malaysia and other countries.

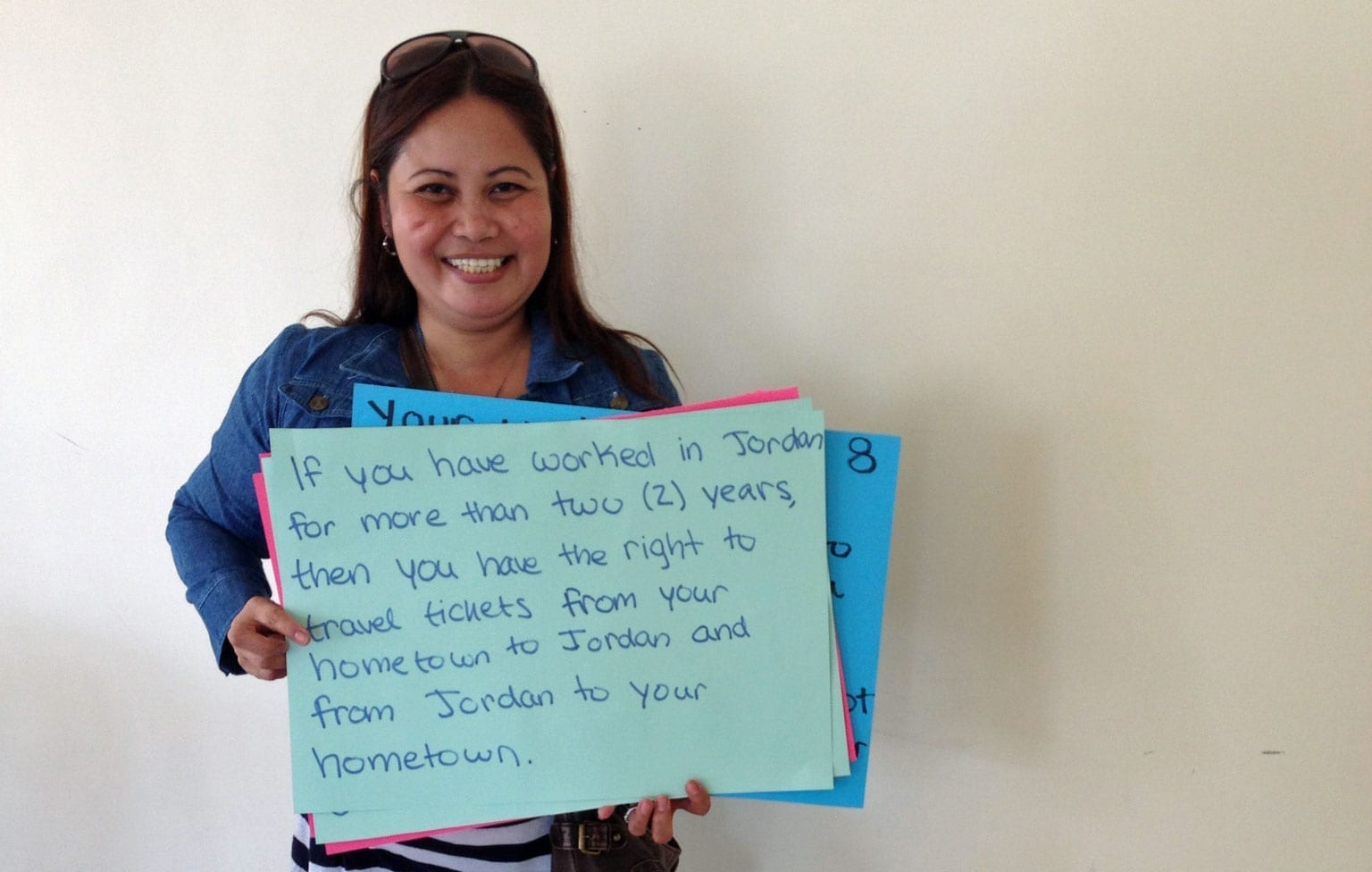

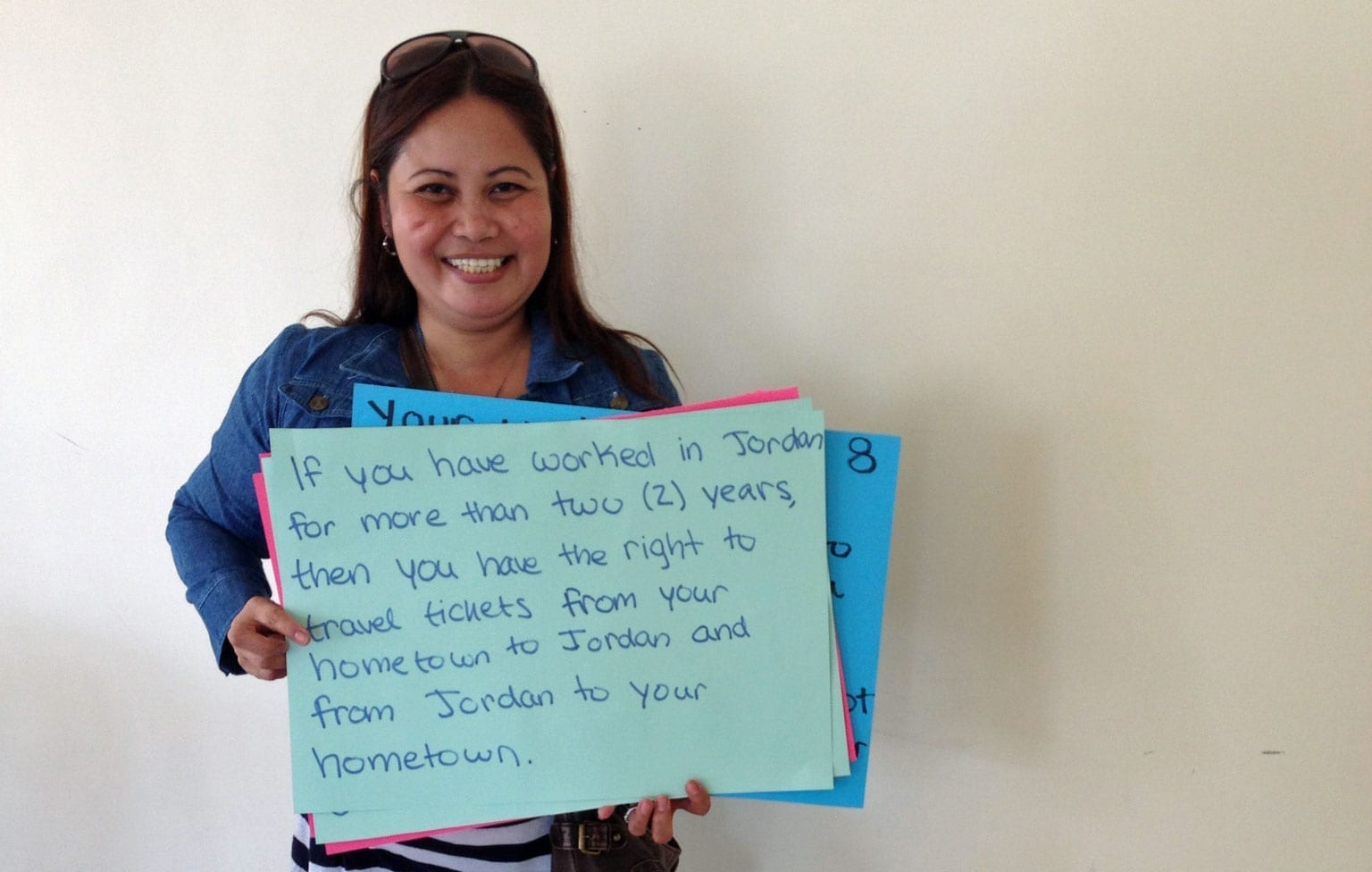

In Jordan, the Solidarity Center is assisting domestic workers build support for their rights on the job. In a first-of-its-kind network, some 250 domestic workers meet regularly, with translation conducted simultaneously in three, or sometimes four, languages. The Domestic Workers Network in Jordan is cooperating with the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF), which formed to help push the ILO Domestic Workers convention and which now represents workers around the world.

Panel participants pointed to the common experiences of those who migrate for jobs, especially domestic workers. After they arrive in the destination country, their cell phones often are confiscated and contact with their families is limited. They are completely excluded from the country’s labor laws, typically do not get any days off and generally do not receive the wage they were promised.

Varia likened the experience of migrant domestic workers to abusive domestic violence situations in which employers exert power by withholding food from domestic workers and force them to sleep on the floor or in closet-like spaces.

In their studies, panelists found that when migrant workers understand their rights before they migrate, they are more likely to leave abusive situations quickly, indicating the value of programs that educate domestic workers and other potential migrants in their home countries.

A better solution, they agreed, is the availability of employment at home.

“If people could find good jobs, they wouldn’t migrate,” Varia said.

Other panelists included: Mahendra Pandey, a former migrant worker; Sarah Paoletti, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Transnational Legal Clinic; and Eleanor Taylor-Nicholson, an independent consultant on migrant worker rights. Shannon Lederer AFL-CIO director of immigration policy, moderated the panel, sponsored by the AFL-CIO and Solidarity Center.

Jun 15, 2015

Apparel workers in Honduras formed unions at three factories in recent days with the Central General de Trabajadores Honduras (CGT) and its apparel federation FESITRATEMASH, in a huge victory for workers seeking to improve their basic livelihoods.

Some 9,000 workers at the Canadian-owned Gildan apparel factories in Choloma, San Pedro Sula and Villanueva make T-shirts, sweatshirts and sweatpants. Gildan recently surpassed Fruit of the Loom as Honduras’s largest private-sector employer.

“With the organization of these unions we the workers now have a voice on the job and a mechanism to negotiate over the conditions of work at Gildan,” says Nahun Rodriguez, President of the SITRAGAVSA union at Gildan Villanueva.

Meanwhile, apparel workers at a Fruit of the Loom factory in Villanueva, Honduras, and their CGT-affiliated union SITRAMAVI last week negotiated a first collective bargaining agreement covering 1,200 workers. The workers cut and sew T-shirts and sweatshirts.

The union organizing at the Gildan factories further expands the membership of CGT and FESITRATEMASH, which represent workers at four Fruit of the Loom factories, and is a significant step forward for apparel workers employed by major multinational apparel brands in the country’s export processing zones.

Honduran labor laws meant to protect workers from the health and safety risks posed by textile factory work are rarely enforced, and there is a severe shortage of factory inspectors who can investigate the working conditions of the hundreds of maquilas—many of them sweatshops.

The majority of clothing and textile workers are women who face particular challenges in the workplace, including sexual harassment, denial of maternity leave and forced pregnancy tests during the job application process. Last fall, a Solidarity Center delegation to Honduras found the level of rights violations, repression of activists and economic hardship experienced by millions of workers “overwhelming.”

The recent victories build on years of Solidarity Center training with CGT, including education on workers’ legal rights, fundamental union principles and union organizing. The Solidarity Center also has trained and mentored organizers who conduct worker outreach to further educate workers on their rights, build organizing committees and seek legal registration of unions.

In 2009, CGT represented one apparel union that was nearly disbanded when Fruit of the Loom shut down the factory to avoid bargaining with workers. As part of an internationally backed campaign, the union reached an historic agreement with Fruit of the Loom to reopen the factory, hire back the workers, provide a welfare fund for the workers for the year they were unemployed, recognition of the union and the negotiation of a collective bargaining agreement.

From that victory, the CGT has now has organized workers at nine more factories, and negotiated collective bargaining agreements at six of them. Nine of the 10 are apparel factories and one is an automobile parts manufacturer.

The Solidarity Center also has provided CGT with legal aid to help workers obtain more than $1.7 million of back wages at three factories that closed without paying workers their wages.

Also as part of the multi-year strategy developed with CGT, the Solidarity Center supported CGT in negotiations with employers and the government, achieving a national-level agreement among labor, business and the government that includes providing housing for apparel workers and daycare centers for apparel workers’ children.