Jul 20, 2017

When Mwahamisi Josiah Makori arrived in Saudi Arabia in 2014 at the home of her employer, she was given 20 minutes to rest before beginning her duties as a domestic worker. Her employers held their noses when they greeted her and made her shower outside before allowing her in the house.

Her responsibilities involved cleaning two homes, including that of the employer’s mother-in-law. She was required to take care of the children, and when they spit on her, her employer told her not to complain. She was up all night caring for the baby and by 6 a.m., preparing the family’s breakfast.

She was given a torn, dirty mat to sleep on, and when she requested a new mat, her employer refused, telling her she was only there for work. In the middle of her tasks, she was required to stop and flush the toilet after a family member used the bathroom.

Makori was required to hold the baby throughout the day as she cooked, cleaned and cared for the other children. One afternoon, when she put the baby down to store groceries, the baby crawled to a cabinet. Alarmed, she called out. Her employer began beating her, saying she was making the baby nervous. They took her to the police authorities and told them she slept all day and refused to work.

She finally was able to convince the police of her plight, and an officer told her employer to pay her way home. The employer refused, but the employer’s mother-in-law paid her way to Kenya.

In Kenya, Makori had struggled to support her three children as a single mother. She was desperate for paid employment when her best friend introduced her to a labor broker who was traveling from village to village. Makori could not afford to pay her children’s school fees, and says she felt she had no choice but to leave the country for work.

After three months of nearly non-stop labor in Saudi Arabia, Makori returned to Kenya. Without pay.

Mar 24, 2017

Uzbek human rights defender Elena Urlaeva was released from a psychiatric hospital in Tashkent yesterday where she was imprisoned for 23 days with neither her consent nor a court order to forcibly treat her, according to the Cotton Campaign. Urlaeva’s release follows an international campaign spearheaded by the Cotton Campaign, a global coalition of labor, human rights, investor and business organizations that includes the Solidarity Center.

Urlaeva was detained and beaten by Uzbekistan police the day before she was due to meet with representatives from the International Labor Organization (ILO), International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and the World Bank to discuss state-led forced labor in Uzbekistan.

Urlaeva Repeatedly Detained for Documenting Forced Labor

Urlaeva has documented forced labor in Uzbekistan’s cotton fields for the past 16 years, and has repeatedly been arrested, beaten and imprisoned by Uzbek officials. Last year, she was imprisoned in a psychiatric hospital for more than a month and arrested five times as she spoke with people forced by the government to labor in the country’s cotton fields. She was physically assaulted during the subsequent interrogation. In 2015, Urlaeva was arrested, beaten and forced to injest sedatives, and police confiscated her camera, notebook and information sheet on ILO labor rights conventions.

“A number of times I was put into a psychiatry ward,” says Urlaeva in a video released last November. “They did their best to show to the international community that human rights activists are crazy and they should not be listened to.”

Child Labor Growing in Uzbekistan Cotton Fields

Each fall harvest, some 1 million teachers, medical professionals and others are forced to toil in Uzbekistan’s cotton fields. If they do not participate, they must pay for a replacement worker or lose their jobs. Children also are forced to pick cotton, according to a preliminarily report by the Uzbek-German Forum, reversing a move away from use of child labor in 2013 and 2014.

Uzbekistan, which gets an estimated $1 billion per year in revenue from cotton sales, faced high penalties from the World Bank and other financial institutions for not ending the practice. Rather than change, the government seeks to cover it up.

Urlaeva has been credited with helping significantly reduce child labor in cotton fields, and this year was among human rights defenders in Uzbekistan to receive the International Labor Rights Forum 2016 Labor Rights Defenders Award.

Jan 25, 2017

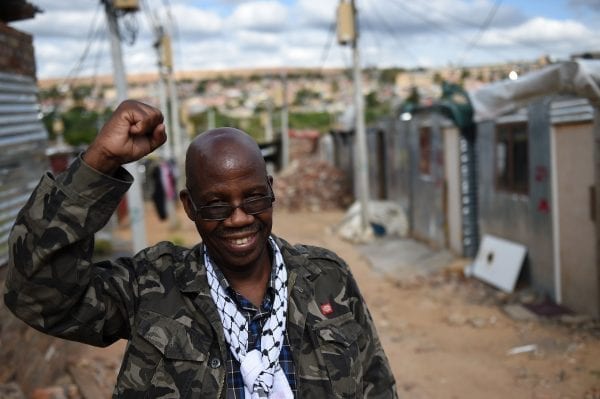

Some 34 million Africans are migrants, and the majority are workers moving across borders to search for decent work—jobs that pay a living wage, offer safe working conditions and fair treatment.

Yet even as they often leave their families in search of jobs that will support them, many migrant workers find that employers seek to exploit them—refusing to pay their wages, forcing them to work long hours for little or no pay, and even physically abusing them.

Throughout the January 25-27 Solidarity Center Fair Labor Migration conference in Johannesburg, South Africa, migrant domestic workers, farm workers and mine workers share their struggles, but also their courage and hope as many join together to form unions and associations to improve their lives at work. Here are their stories.

Fauzia Muthoni Wanjiru left Kenya after a labor broker told her she would work in Qatar as a receptionist. Instead, she was taken to Saudi Arabia, where she was forced to work 18 hours a day as a domestic worker cleaning two homes a day. Her passport was taken, trapping her in the country. “When you go there, you are a slave to them,” she says.

Praxedes moved from Zimbabwe to South Africa so her children would live a better life than she had. “There is nothing for me there (in Zimbabwe), she says. “A lot of employers take advantage of that.” She has worked for more than five years as a domestic worker, and employers have refused to pay her overtime, and shortchanged her pay—even as her transportation costs take up a third of her wages. “My cellphone has to be off at all times. I have three kids. If anything happens to them, I will not know.”

Angela Mpofu migrated from Zimbabwe to support herself and her family as a domestic worker in South Africa. But like many migrant workers, she finds that she is treated poorly, as employers take advantage of her migrant status. Worse, says Mpofu, “the way (employers) treat us, it’s like we are not human beings. You’re nothing to them.”

As a migrant mine worker from Swaziland, Mduduzi Thabethe says he has fewer workplace rights than his South African co-workers. Although all mine workers pay the same amount into the health fund, migrant workers get inferior care and pensions are rare. “If you are a citizen of South Africa, you see you are building your country and you have something, but we have nothing.” His union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, is working to improve conditions for migrant workers.

When Joe Montisetse came to South Africa from Botswana to work in gold mines in the early 1980s, he saw a black pool of water deep in a mine that signified deadly methane. Yet after he brought up the issue to supervisors, they insisted he continue working, but Montisetse refused. Two co-workers were killed a few hours later when the methane exploded. Today, with the National Union of Mineworkers, Montisete, deputy president of the union, says workers are safer now. “We formed union as mine workers to defend against oppression and exploitiation,” says Montisetse.

In 2000, Chris Muwani migrated from Zimbabwe to South Africa, where he works on a tomato farm. If he does not fulfill his daily quota, he is not paid for the day. Migrant farm workers like Muwani are exposed to dangerous workplace conditions and without a union, cannot exercise their rights. “We use a chemical to spray grass but you don’t have rubber boots or a respirator but you are working with poison,” says Muwani. “If you protest about safety conditions, many people are fired.”

As a migrant farm worker from Mozambique, France Mnyike receives no health care coverage, even for workplace injuries. When Mnyike broke his leg at work, his employer did not provide medical aid and his leg remains fractured. Even if his workplace offered emergency care, says Mnyike, the employer would “deduct the cost from your salary.”

Nov 9, 2016

When the employer of a migrant domestic worker takes her passport and refuses to return it if she seeks to leave, that is forced labor.

When a family works at a brick kiln to pay off a debt, their children prevented from attending school, that is forced labor.

When Uzbek teachers and doctors are mandated by the government to spend two months each fall picking cotton, that is forced labor.

Around the world, nearly 21 million people are forced laborers—11.4 million women and girls and 9.5 million men and boys. Ninety percent of forced labor takes place in the private economy, where it generates $150 billion in illegal profits per year.

Today, an International Labor Organization (ILO) Protocol on Forced Labor enters into force, requiring countries that ratify it to ensure the release, recovery and rehabilitation of people living in modern slavery. Adopted by the ILO in 2014, the protocol also protects workers from prosecution for any laws they were made to break while they were in forced labor.

The protocol and the accompanying recommendation supplement the 1930 ILO standard covering forced labor, Convention 29, and gives “new impetus to the global fight against all forms of forced labor, including trafficking in persons and slavery-like practices,” according to the ILO.

The protocol also bolsters the ILO’s 1957 Abolition of Forced Labor Convention 105. (Here’s a summary of the two forced labor conventions and the protocol.)

Protocol Would Compensate Those in Forced Labor

Among its provisions, the protocol:

- Guarantees forced laborers access to justice and compensation—even if they’re not legal residents of the country where they work.

- Protects individuals, especially migrant workers, from possible abusive and fraudulent practices during the labor recruitment and placement process.

- Requires employers to exercise “due diligence” to avoid modern slavery in their business practices or supply chains.

Nigeria was the first country to ratify the protocol and since then, eight more countries have done so. The ILO is urging people to join its 50 for Freedom campaign, which aims for 50 countries to ratify the protocol by 2018 to be truly effective.

Join Campaign Urging Countries to Pass Protocol!

Send a message to your labor minister urging passage of the protocol here. The action is hosted by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), which is a member of the 50 for Freedom coalition, as is the Solidarity Center.

You also can sign up to get more information on the campaign and spread the word to your networks and on social media with the hashtag #50FF.

Additional 50 for Freedom materials include:

Sep 28, 2016

At least one person has died in Uzbekistan cotton fields so far this season, part of the country’s massive mobilization of compulsory labor in which nurses, teachers, students and state employees are forced from clinics and classrooms to toil for weeks picking cotton.

Komiljon Asimov, 20, a biology student at Abduhab State University, died September 11, days after university students were the first group mobilized by the Uzbek government for the fall cotton harvest. In another incident, Dilarom Juraev, 28, suffered a miscarriage in the fields.

Each harvest, Uzbekistan mobilizes more than 1 million residents to pick cotton through systematic coercion. From September through October, many classrooms shut down because teachers are among those forced to pick cotton. Health clinics and hospitals are unable to function fully with so many health care workers also toiling in the fields.

‘You Work Like a Slave from Morning to Night’

“Dinner takes place in the field again. For the dinner we are normally given watery soup,” writes one university economics student from the Andijan Agricultural Institute, who is now picking cotton. “I have no strength left. You work like a slave from morning till night, not enough food, and should sleep and wake up hungry again.”

The student, whose story was collected by the Uzbek-German Forum (UGF), describes being forced from her studies with other classmates to take part in the government-led mobilization. They are housed in a local school building emptied of students, where they sleep on a cold floor, with no showers and limited sanitary facilities.

The student says she spent hundreds of dollars of her family’s money buying food and warm clothing to prepare for working some two months in the cotton fields. Nearly 10,000 students from the four universities in the Andijan region were forcibly sent to work starting September 8.

Uzbeks Coerced into Signing ‘Voluntary Participation’ Letters

Last year, the government went to extreme measures—including jailing and physically abusing researchers independently monitoring the process—to cover up its actions. This year, the tactic appears to be widespread coercion of students, health care workers and others to sign letters indicating they are “voluntarily” participating in the cotton harvest, according to UGF. Employees are told they will lose their jobs and students threatened that they will be expelled from the university if they do not pick cotton or agree to gathering a set weight of cotton each day.

In one video, Alia Madalieva, the head nurse at Clinic No. 8 in Kokand City, dictates to employees the text for their “letter of commitment.” Seated next to a clinic employee in the cotton fields, she dictates: “If I do not collect 50 kg (kilograms) of cotton a day, I will voluntarily hand in my letter of resignation. I wrote this on my own.”

Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, another country where forced labor in cotton harvests is rampant, this year were downgraded to the lowest ranking in the U.S. State Department’s 2016 Trafficking in Persons Report. Uzbekistan, which gets an estimated $1 billion per year in revenue from cotton sales, also forces farmers to plant state-ordered acreage of cotton and wheat or face the loss of their land.

More personal stories from those forced to pick cotton and other documentation are available at UGF’s new microsite. The UGF is a member of the Cotton Campaign, as is the Solidarity Center, The campaign works to end the injustice of forced labor in cotton harvesting in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.