Jun 17, 2015

Hundreds of thousands of workers in the Dominican Republic without official identification papers have until today to register with the government or face deportation. The move—condemned widely as a violation of human rights—could leave as many as 120,000 Dominican-born and -raised women and men stateless, their future and their ability to earn a living jeopardized. If they cannot regularize their status, their next stop, as soon as tomorrow, may be the Haitian border.

Dominicans of Haitian descent have long faced exploitation and discrimination and experienced trouble obtaining official documentation, despite spending their entire lives in the country. Many speak only Spanish and have few, if any, ties to neighboring Haiti. However, a controversial 2013 Constitutional Court decision ruled that that individuals who were unable to prove their parents’ regular migration status could be retroactively stripped of their Dominican citizenship. While a later presidential decree recognized the citizenship of roughly 68,000 people, an additional 130,000 Dominican natives who never had documents were forced to prove birth in the Dominican Republic country to apply for Haitian citizenship and, with Haitian documents, apply for regularization in the country of their birth. Only about 10,000 of these people applied under the plan.

A 2014 report by the Solidarity Center and AFL-CIO, “Discrimination and Denationalization in the Dominican Republic,” called the ruling an “egregious abuse of fundamental human rights and a clear violation of international law.” Indeed, said the report, the actions by Dominican officials leading up to and following the ruling “demonstrate the depths of entrenched discrimination.”

In September 2014, Dominican unions and human rights groups raised concerns that the registration process was fraught with irregularities, unnecessary hurdles and bureaucracy. They said some local agencies were charging exorbitant fees for documents that were supposed to be provided for free and which applicants needed to demonstrate long-term residence. They said some workers had waited months for notification of the results of their applications, even though the law stipulates a response within 45 days.

Said Alexis Rosalie, spokeswoman for the National Coordinator for Immigration Justice and Human Rights and an organizer for the National Federation of Workers in Construction and Building Materials (FENTICOMMC), at the time: “We have proof there are people who meet all the basic requirements of the National Plan for Regularization of Foreigners (PNRE), and each time they go back to the offices, they are always told they are lacking one document or another.”

According to a report today by The Guardian newspaper, only 300 people applying for official identification received it.

Shawna Bader-Blau, executive director of the Solidarity Center, said: “We are astounded by this deliberate creation of a stateless underclass. Tens of thousands of people who live on the margins today and could be separated from their loved ones, their social networks, their jobs—all that is keeping them barely afloat—tomorrow.”

In past weeks, representatives of the Network of Support to Migrant Workers of the National Confederation of United Trade Unions (CNUS) and the Migrant Justice Movement, a grouping of unions and migrant organizations formed at a 2014 advocacy training organized by the Solidarity Center, held a series of press interviews calling for an extension to the regularization plan. Other groups, including Amnesty International, are calling on the government to respect international law and standards, and to “establish adequate mechanisms to avoid the expulsion of Dominican-born people who were deprived of their Dominican nationality in September 2013, including a specific screening process targeting Dominicans of Haitian descent.”

Jun 16, 2015

On a trip to Kuwait two years ago, Nisha Varia from Human Rights Watch visited a hospital where two rooms were filled with injured domestic workers who had tried to escape from their employers’ homes. Trapped in abusive situations, the women jumped from windows or were beaten by employers as they sought to leave.

The experience for domestic workers in Middle Eastern Gulf states, and in many countries around the world, has not significantly improved since then, said Varia and others at a recent panel in Washington, D.C., “Migrant Workers in the Gulf States: Transnational Policy Responses to Protect Labor Rights.”

In the Gulf, “employers feel they have bought domestic workers because they paid the recruitment fee,” Varia said. The situation is exacerbated in Gulf countries by the kefala system, which ties employment of foreign workers to their employers, and makes it illegal for workers to get another job in the country. Employers also typically take the passports of domestic workers, who toil unseen from the public and are especially vulnerable to abuse.

June 16, International Domestic Workers Day, marks the fourth anniversary of the adoption of the United Nations Convention 189 on Domestic Workers, a landmark standard championed by unions, civil society groups and human rights organizations worldwide. Its passage signaled the global community’s recognition that the 53 million workers who labor in households, often in isolation and at risk of exploitation and abuse, deserve full protection of labor laws.

The historic action indicated the recognition that domestic workers, 83 percent of whom are women, perform work—and that entails rights equal to all other wage earners. Eighteen countries have ratified the Convention since its passage. (ILO resources for and information on domestic workers here.)

The panel, which encompassed broader issues of labor migration, highlighted the overlap between domestic workers and migrant workers. The Solidarity Center works with domestic workers in countries such as Dominican Republic, where most domestic workers are from Haiti and in Jordan, where domestic workers have migrated for work from the Philippines, Malaysia and other countries.

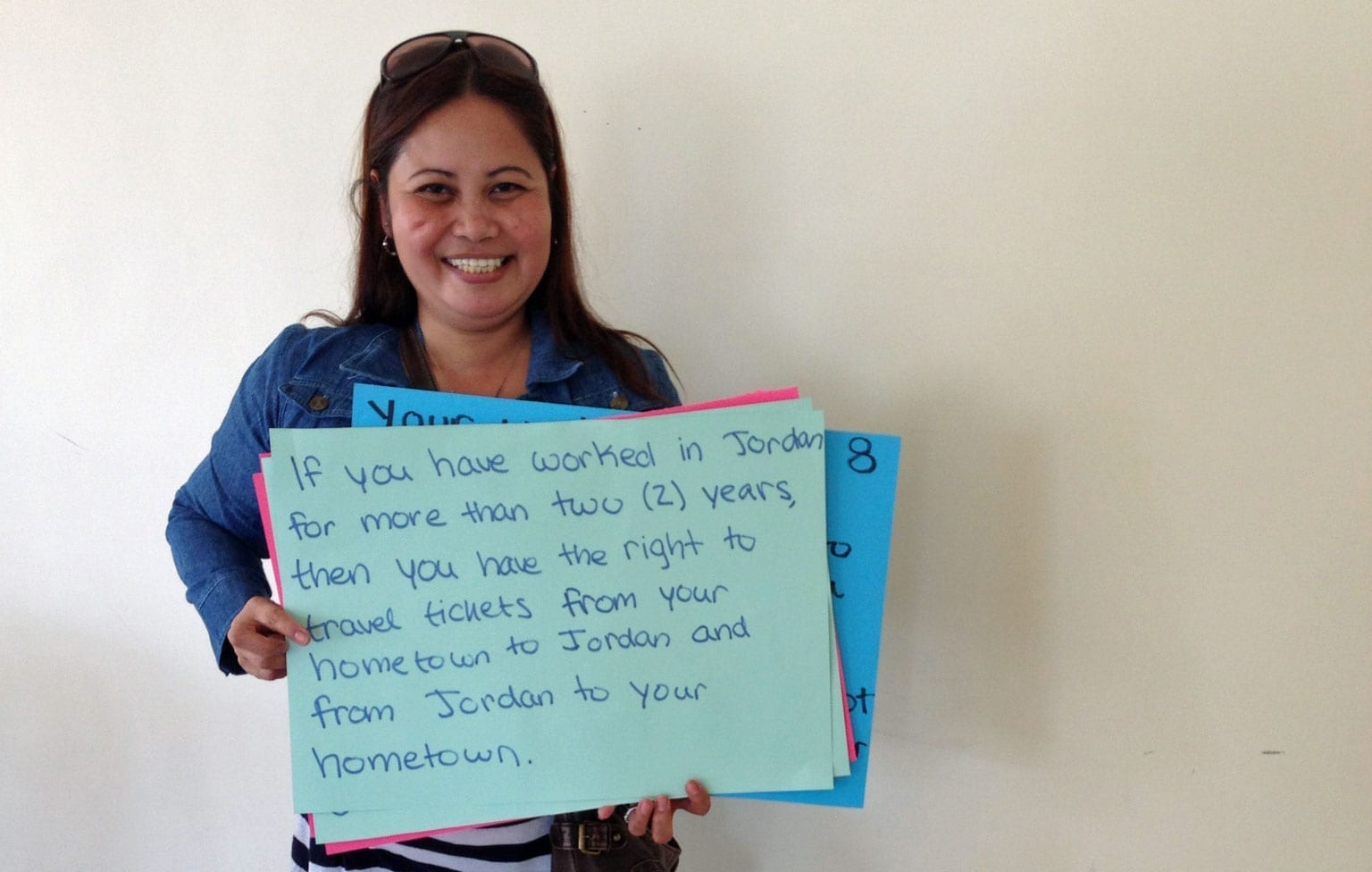

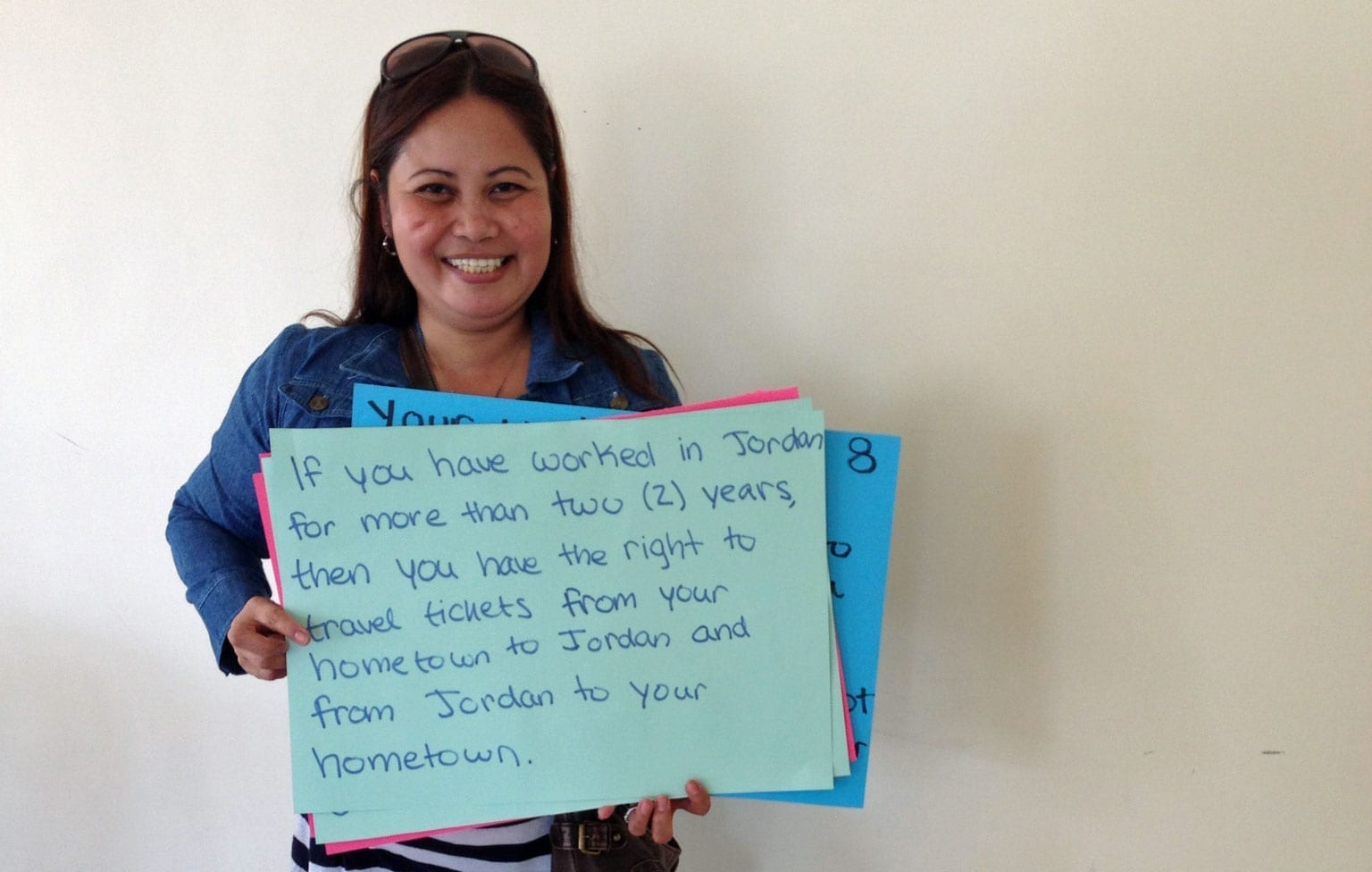

In Jordan, the Solidarity Center is assisting domestic workers build support for their rights on the job. In a first-of-its-kind network, some 250 domestic workers meet regularly, with translation conducted simultaneously in three, or sometimes four, languages. The Domestic Workers Network in Jordan is cooperating with the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF), which formed to help push the ILO Domestic Workers convention and which now represents workers around the world.

Panel participants pointed to the common experiences of those who migrate for jobs, especially domestic workers. After they arrive in the destination country, their cell phones often are confiscated and contact with their families is limited. They are completely excluded from the country’s labor laws, typically do not get any days off and generally do not receive the wage they were promised.

Varia likened the experience of migrant domestic workers to abusive domestic violence situations in which employers exert power by withholding food from domestic workers and force them to sleep on the floor or in closet-like spaces.

In their studies, panelists found that when migrant workers understand their rights before they migrate, they are more likely to leave abusive situations quickly, indicating the value of programs that educate domestic workers and other potential migrants in their home countries.

A better solution, they agreed, is the availability of employment at home.

“If people could find good jobs, they wouldn’t migrate,” Varia said.

Other panelists included: Mahendra Pandey, a former migrant worker; Sarah Paoletti, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Transnational Legal Clinic; and Eleanor Taylor-Nicholson, an independent consultant on migrant worker rights. Shannon Lederer AFL-CIO director of immigration policy, moderated the panel, sponsored by the AFL-CIO and Solidarity Center.

Feb 13, 2015

One of the five Haitian workers shot at a Dominican Republic construction site shows his wounds.

Five Haitian construction workers in the Dominican Republic were shot allegedly for asking for unpaid wages, according to press reports. In addition, an eyewitness told Solidarity Center staff in Santo Domingo, the capital, that on February 2, a sergeant of the National Army fired upon and wounded the five workers, who were not taken to a hospital until a delegation from the Haitian Embassy arrived.

The witness, who provided photos of the incident and spoke with Solidarity Center staff on February 10, claimed he spoke with one of the soldiers involved, and the soldier said he was paid by the construction engineer to prevent the workers from entering the construction site and to fire on the workers.

The workers had been working on the construction site of the hospital Dario Contreras.

A September 2013 court ruling targeted migrants in the Dominican Republic, revoking the citizenship of individuals born in the country since 1929 who could not prove their parents’ regular migration status.

On February 2, the deadline expired for Dominicans born to undocumented parents to apply for migrant permits, leaving thousands stateless. The process for documentation was rife with irregularities, making it difficult for anyone to receive official status.

Jan 29, 2015

Amparo Lara sells plantains in San Cristobal’s Municipal Market, vying for customers along with dozens of other vendors selling mangoes, guavas and a range of vegetables and herbs along with services, such as shoe repair.

The increasing lack of full-time jobs around the world has forced many working people like Lara to seek a living in the precarious informal economy. These market vendors, domestic workers, pedicab drivers and day laborers work for meager wages in jobs unregulated by safety and health standards and typically have no access to pensions, sick leave or worker compensation.

[portfolio_slideshow id=2803]

The Solidarity Center helps workers in the informal economy come together to gain the knowledge and confidence to assert their rights and raise living standards. In 35 countries, we provide trainings and programs to help precarious workers better understand their rights, organize unions to mitigate job vulnerabilities, and learn to bargain for improved conditions and wages.

In the Dominican Republic, where a thriving informal economy includes both Dominicans and Haitians, the Solidarity Center has mobilized many of these workers, forming an organization where they can better stand up for their rights and improve their wages and working conditions.

Through the Féderacion Nacional de Vendedores de los Mercados (FENAVEMER), street sellers like Lara have a collective voice on the job, enabling them to better seek their share of the country’s economic prosperity.

Oct 23, 2014

The Inter-American Court for Human Rights ordered the Dominican Republic to reform all national laws blocking the recognition of citizenship for children of undocumented parents born in the country.

The decision, dated August 28, 2014, was made public on October 22, 2014, according to a story today in El Dia, a national newspaper in the Dominican Republic. The sentence orders the country to adopt the necessary measures to ensure no laws or rules deny Dominican nationality to children born in the country to undocumented parents who migrated there.

The decision comes in a case in which 27 people were deported, five of them Haitian children residing in the Dominican Republic and 22 of whom were found to be Dominicans.

“The Court found the existence, at least for a period of around one decade after 1990, a systematic pattern of expulsions, including through collective acts of Haitians and people of Haitian descent, which reflects a discriminatory conception,” according to El Dia, quoting the court statement. The Inter-American Court for Human Rights is part of the Organization of American States.

In September 2013, the Dominican Republic’s Constitutional Court revoked the citizenship of individuals born in the country since 1929 who could not prove their parents’ regular migration status.

The ruling would have barred such individuals from any activity that required official identification, including working in the formal sector, attending school, opening a bank account, paying into retirement or social security funds, accessing health services, getting married, traveling or voting, according to an AFL-CIO and Solidarity Center report.

Further, it disproportionately affected individuals of Haitian descent living and working in the Dominican Republic.

Hailing the court decision, Geoff Herzog, Solidarity Center Dominican Republic country program director, said, “the Solidarity Center joins with our union allies and with our allies in the migrant support community in defense of migrant worker rights.

“We support recognition of citizenship for Dominicans of Haitian descent who are blocked from citizenship and therefore, are denied their basic human and labor rights.”