Jul 19, 2018

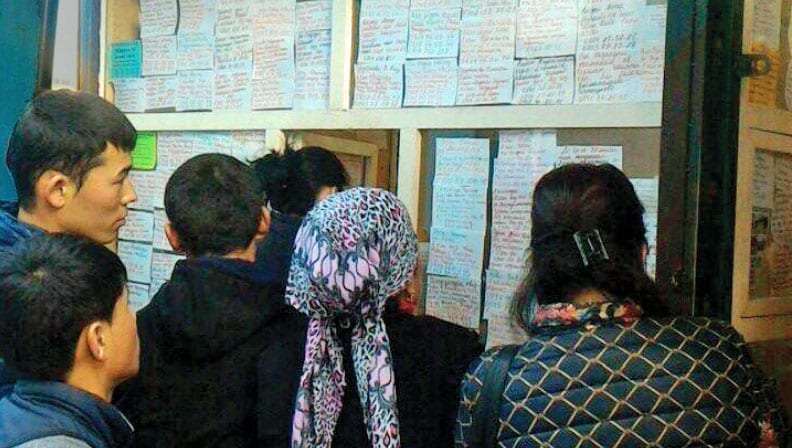

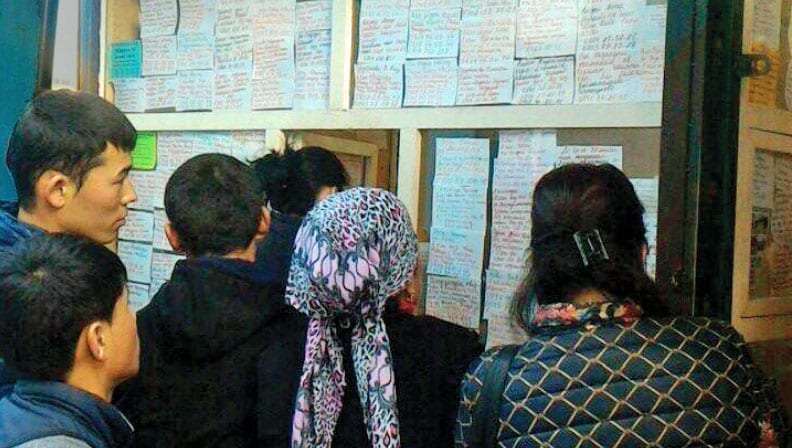

Workers who migrate from Kyrgyzstan to Kazakhstan for jobs often do not receive their wages, are forced to work in unsafe and abusive conditions and even are kidnapped and held against their will in forced labor, according to a new report.

“Invisible and Exploited in Kazakhstan” also found that children are forced to labor, with young girls between ages 12 and 17 working as nannies, and boys working in markets and on farms. The report is based on the findings of a series of missions by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and its partners from September to November 2017 in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. The Solidarity Center contributed extensively to the report.

“The right to freedom of association is a core principle of human rights and worker rights, including when workers are migrating for jobs,” says Lola Abdukadyrova, Solidarity Center program coordinator. Abdukadyrova spoke yesterday at a press conference in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, where the report was released.

Bedroom of five migrant workers in the basement of a construction site in Kazakhstan, November 2017. Credit: FIDH

Between 100,000 to 150,000 Kyrgyz were registered in Kazakhstan at the end of 2017, figures that do not reflect many who are not registered. Most work without written contracts or on contracts that do not adequately protect their rights. Their passports typically are confiscated, making it difficult for them to leave abusive employers, and they have no access to labor protections like safe working conditions and paid leave.

“The lack of labor agreements entails forced labor and even slavery,” says Aina Shormanbayeva, speaking at the press conference, which drew nearly two dozen reporters. Shormanbayeva is president of the Legal Initiative, a Kazakhstan-based public foundation.

Some 81,600 workers were victims of forced labor in Kazakhstan in 2016, according to estimates by the nonprofit Walk Free Foundation, with migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan forced to labor in agriculture, construction and the extraction industry.

Women Migrant Workers Targets of Gender-Based Violence

While some one-third of all migrants were women two to three years ago, the report finds women now comprise half of migrant workers. Women are especially vulnerable, facing gender-based violence in agricultural fields and in employers’ homes when working as domestic workers. They may lack medical care while pregnant and often are fired when employers learn of their pregnancy.

Says one woman migrant worker: “I work as a janitor from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., and when there are banquets, until 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. Lunch breaks are 30 minutes maximum. There are no days off. I work every day. Some people can’t prove anything when they don’t get paid because nothing is documented. One woman worked at a car wash, they told her they didn’t have money and so they didn’t pay her. This happens to many people.”

Solidarity Center’s Lola Abdukadyrova, (second from left), discussed the plight of migrant workers in Kazakhstan during a press conference in Bishkek. Credit: Solidarity Center

The report finds migrant workers are not aware of their rights on the job, and they rarely appeal for protection of their rights when their employers perform illegal actions. They also do not believe police are able to protect their rights. In many cases, officers of law enforcement agencies are the link between migrant workers and buyers.

“Kazakhstan has not taken effective measures to prevent, investigate and prosecute persons involved in providing illegal intermediary services, and has not ensured effective legal protection for the victims,” the report states. Kazakh authorities argue that it is not their responsibility to protect migrant workers, and that protection of migrant workers is the responsibility of Akims (heads of regional or local authorities).

Kazakhstan was recently rated one of the 10 worst countries for workers by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). Union leader Larisa Kharkova was sentenced in 2017 to four years of restrictions on her freedom of movement, a ban on holding public office for five years and 100 hours of forced labor on false charges of embezzlement. Kharkova led the Confederation of Independent Trade Unions of Kazakhstan, which was ordered closed by a court ruling. Independent trade unions in Kazakhstan face ongoing attacks on freedom of association and basic trade union rights.

Over the past five years, the Solidarity Center in Kyrgyzstan has worked extensively to advance migrant worker rights, including holding awareness-raising campaigns for potential migrants and their families; supporting a hotline on labor migration issues; and assisting unions in protecting and promoting migrants’ worker rights.

Jul 19, 2018

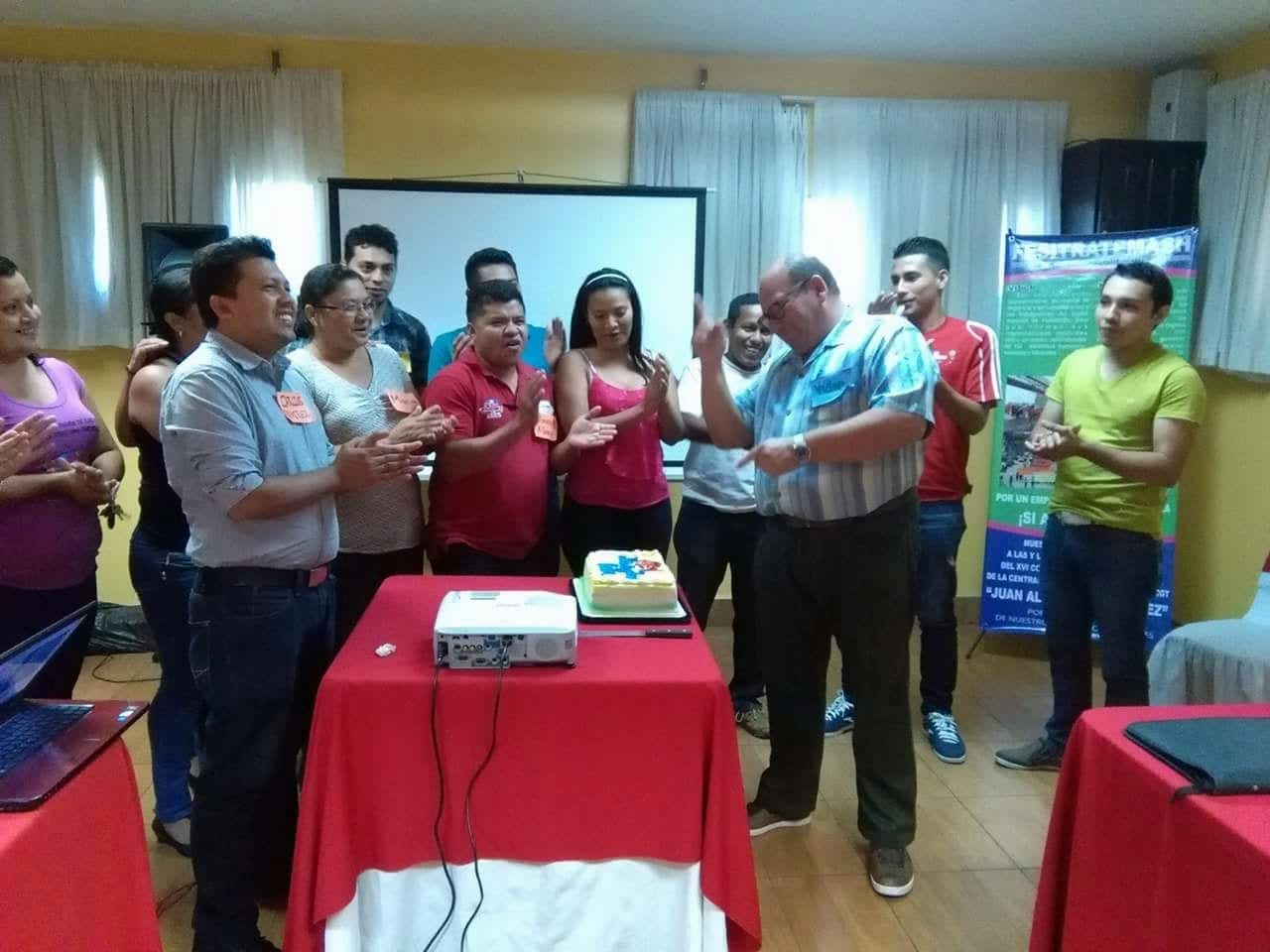

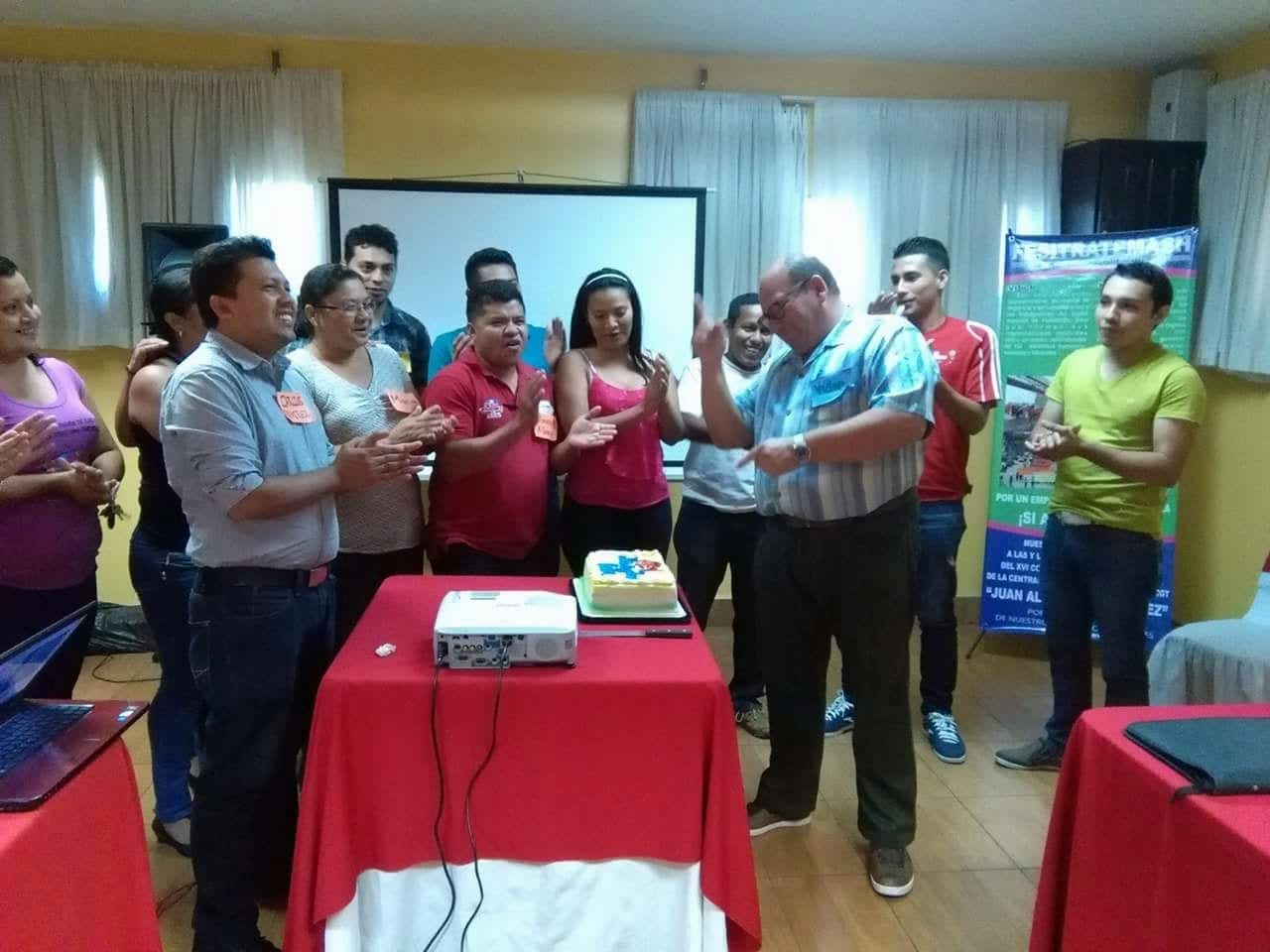

The Solidarity Center is mourning the loss of Victor Hugo Quesada Arce, Solidarity Center project coordinator in Costa Rica, who died July 16 after a battle with cancer.

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”

In his 30 years of strengthening unions and educating workers about their rights, Victor worked side by side with some of the most vulnerable and marginalized workers in the region. He helped revitalize plantation worker unions which primarily represent migrant workers in Costa Rica and which had been decimated by decades of anti-union assaults.

Victor came to the Solidarity Center five years ago as a worker rights advocate well-known across the region, and agriculture unions from throughout Central America have been sending tributes and an outpouring of appreciation for his many years of solidarity and support.

“We stand in solidarity and send hugs to friends, relatives of our brother Victor,” writes FESTAGRO, the agriculture union in Honduras. “People like you are one of a kind, and are always remembered.”

Jul 18, 2018

Worker rights advocates are hailing a recent court decision in Thailand that dismissed criminal defamation charges against 14 migrant workers from Myanmar who faced jail time after reporting abusive working conditions on a poultry farm.

Fourteen workers who left the farm in 2016 described forced overtime, unlawful salary deductions, confiscation of passports and restrictions on freedom of movement in a complaint to the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand.

In retaliation against the workers for submitting the complaint, the Thammakaset Co. Ltd. filed a criminal defamation complaint against the 14 workers, alleging they falsified claims to damage its business interests.

The case put a spotlight on abuse in the supply chain, says Solidarity Center Asia Regional Director Tim Ryan. The ruling “strikes a blow against the criminalization of promoting labor rights,” and is a landmark for migrant worker rights and freedom of expression.

“Companies filing criminal defamation complaints against workers who seek justice on the job is an all-too common practice, one often used as justification for dismissal. This decision is in line with international legal standards supporting free speech, freedom of assembly and other activities key to an open civil society.”

Workers Increasingly Migrate for Jobs

One of the migrant workers says he worked 22-hour shifts for more than four years at the Thammakaset 2 Poultry farm, which supplies one of Thailand’s largest chicken export companies. Myint told the Guardian that each day, he would kill up to 500 birds for food processing. At night, he and his co-workers say they slept on the floor in a room with up to 28,000 chickens, swatting away insects. If a bird got sick, they were to blame.

Of the 232 million migrants around the world, 150 million are migrant workers. Millions of migrant workers like Myint and his co-workers are unable to find family-supporting jobs in their origin countries. With labor migration increasing as men and women seek to support their families, the case highlights the rights of migrant workers seeking justice for workplace abuse.

A team of United Nations human rights experts this year called on Thailand to “end recurring attacks, harassment and intimidation of human rights defenders, union leaders and community representatives who speak out against business-related human rights abuse.”

Referring to the Thammakaset case, they said “business enterprises have a responsibility to avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts; therefore it is a worrying trend to see businesses file cases against human rights defenders for engaging in legitimate activities.”

Thammakaset also filed a criminal complaint against two of the 14 workers and a Migrant Worker Rights Network coordinator for the alleged “theft” of time cards, taken by the workers to show labor officials evidence of their claims about a 20-hour working day. MWRN, a Solidarity Center partner, is a membership-based organization for migrant workers from Myanmar working in Thailand.

Jul 12, 2018

Click here to read what civil society has to say about AGOA.

The goal of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and similar U.S. trade preference programs and agreements should be to reduce income inequality and increase good jobs, say worker rights organizations, unions and civil society experts. Those outcomes will not be achieved unless governments consult with their citizens on deals that impact their lives and livelihoods.

Shawna Bader-Blau, Solidarity Center Executive Director, left, moderates a panel discussion including Caroline Khamati Mugalla, Executive Secretary of the East African Trade Union Confederation. Credit: Tula Connell

Representatives of several African and U.S. nongovernmental organizations and trade unions spoke on July 10, 2018, at a panel discussion in Washington, D.C., “Ensuring Inclusive and Equitable Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa through AGOA,” which focused on the path forward for AGOA in the remaining seven years before it expires in 2025. The event was organized by the Solidarity Center.

“Yes, we want trade. And, yes, we want trade to work for people,” said Shawna Bader-Blau, Solidarity Center executive director, who restated the organization’s decades-long commitment to a rights-based approach to economic policy and rules that work for working people, which Bader-Blau described as “economic development for everyone, globally.”

Africa is not a poor continent, said Caroline Khamati Mugalla, executive secretary of the East African Trade Union Confederation (EATUC). The problem is not poverty, she said, but that “wealth is not getting to the people.”

More than 80 percent of workers on the African continent—of whom more than 50 percent are women—are in the informal sector, which often means, said Mugalla, a lifetime of poverty due to low wages, lack of access to social protections like pensions and health care, and any rights ascribed to workers in the formal sector under national and regional labor laws.

“We are told any job is a good job, but this is not true,” said Mugalla, who argued that the growth of decent employment is central to structural economic transformation of Africa.

Kwabena Nyarko Otoo, director of the Policy and Research Institute of the TUC-Ghana shared on a panel discussion on the way ahead for AGOA. Credit: Tula Connell

“We need to recalibrate AGOA so it strengthens the productive capacities of African countries—so there are more good jobs for Africans,” agreed panelist Kwabena Nyarko Otoo, economist and director of the Policy and Research Institute of Ghana’s trade union federation, Trades Union Congress (TUC). Otoo argued against foreign companies exploiting opportunities provided by AGOA to enrich themselves and top management rather than providing skilled, formal-sector, well-paid jobs to local populations.

“I do think trade tools are incredibly powerful because governments do care. They are somewhat underutilized by civil society groups and labor, especially in the AGOA context,” said Scott Busby, Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (DRL) at the U.S. Department of State. “I do think trade tools can and should be part of how we support democracy and human rights.”

“The AGOA labor provision requires countries to make continual progress toward establishing worker rights, including acceptable conditions of work,“ said Matthew Levin, director of Trade and Labor Affairs at the Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB), U.S. Department of Labor. “AGOA hasn’t done everything we wanted, but we’ve had some successes.”

Marie Clarke, Executive Director, Action Aid USA. Credit: Tula Connell

Marie Clarke, executive director of ActionAid USA, said about AGOA that, if we are going to use it as “a tent to address and protect the rights of people,” civil society must insist that the people most affected by policies like trade agreements be at the table—especially when the goal is women’s empowerment and more equitable and just development. To combat exploitation and gender-based violence at work, she added, “women must get to share their experience as a worker, as a woman [at the negotiating table].”

This call for a human rights approach to development was mirrored by Sam Worthington, InterAction chief executive officer. “There is a myth that economic growth leads to development. It does not,” he said.

Inclusive economic growth occurs when the demand for it comes from within, said Worthington, when civil society groups and labor “make it happen.” Support for the trade agreement in Africa will diminish, he warned, unless AGOA is used as a tool for development instead of exclusively for economic growth.

The Solidarity Center’s Molly McCoy, Policy Director, left, with Cassandra Waters, AFL-CIO Global Worker Rights Specialist. Credit: Tula Connell

Workers are always in the best position to monitor and enforce working conditions, said AFL-CIO Global Worker Rights Specialist Cassandra Waters. “The real test is in implementation,” she said.

“You cannot help people if you don’t listen to them,” said Otoo, who advocated for workers to be included in all aspects of trade agreements, including negotiations and implementation.

In a statement distributed at the 17th Africa Growth and Opportunity Act Forum in Washington, D.C. on July 11, 16 civil society organizations called on African and U.S. governments to work more closely with civil society to ensure AGOA trade preferences benefit more than the elite. The forum is attended by trade ministers from sub-Saharan African countries benefiting from AGOA and U.S. government representatives.

AGOA provides preferential access to U.S. markets for qualifying sub-Saharan countries. To qualify and remain eligible for AGOA, each country must be working to improve its human and worker rights record and respect the rule of law. In 2014, the United States suspended Swaziland from AGOA for failing to allow worker and civil society groups to freely associate and assemble. In December last year, after the government had met a series of benchmarks on political freedom, Swaziland’s trade benefits under AGOA were restored.

Jul 11, 2018

The Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) has done little to build economies that work for all Africans but, if better utilized and combined with meaningful commitments to human rights and development, AGOA could undergird the establishment of strong, sustainable and diversified economies in sub-Saharan Africa, say 16 civil society organizations.

In a statement distributed today at the 17th Africa Growth and Opportunity Act Forum in Washington, D.C., the organizations—among them trade unions and anti-poverty, religious, social justice and worker rights groups from Africa, Europe and the United States—called on African and U.S. governments to work more closely with civil society to ensure AGOA trade preferences benefit more than the elite. The forum is attended by trade ministers from sub-Saharan African countries benefiting from AGOA and U.S. government representatives.

The Solidarity Center is among the signatories to the statement, which offers recommendations on economic diversification, worker rights, human rights and closing civil society space, gender equality and corruption.

AGOA, enacted in 2000, has been renewed through 2025. The legislation provides U.S. market access to sub-Saharan African countries that demonstrate efforts to protect worker and human rights, reduce poverty, combat corruption and respect the rule of law.

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”