Jul 14, 2021

Worker rights advocates and the international human rights community are expressing sorrow, disbelief and outrage over the horrific fire at the Hashem Foods Ltd., factory in Bangladesh that killed at least 52 workers and more than a dozen children early this week. News reports say factory exits were locked, trapping the 200 workers inside. Three workers died jumping from the burning building.

“We believe that the fire has occurred as a result of non-compliance with law and safety regulations of the institution. This amounts to murder committed by the factory,” three major union federations said in a statement. Chemicals and flammable substances like polythene and clarified butter contributed to the blaze in the factory, and made it more difficult to bring under control, according to CNN.

The Bangladesh Garments and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF), Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation (BIGUF) and Bangladesh Center for Workers Solidarity (BCWS) went on to call on the government to immediately investigate the cause of the fire and to provide fair compensation to those injured and to the families of those killed.

The owner and several top officials at the factory, owned by Bangladeshi conglomerate Sajeeb Group’s subsidiary Hashem Foods Ltd., have been arrested on murder charges. Some 2,035 people work in 11 factory buildings of Hashem Foods, which produces juice drinks, cookies and other snacks.

The fire amounts to “premeditated murder,” says Nahidul Hasan Nayan, general secretary of the Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF). “Workers whose sweat has built palaces lost their lives due to the greed of owners, their lack of accountability, irresponsibility, brutality and lack of safety at work. We demand the culprits to be brought to swift justice.”

Bangladesh Accord Must Be Renewed

Worker rights advocates say the Hashem factory fire highlights the need for multinational brands to renew the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, a landmark agreement that made factories safer for 2 million garment workers. Signed by fashion brands and unions in 2013, the Accord was set apart from previous safety agreements because it was legally binding, providing a key enforcement mechanism for workers and their unions to hold individual brands and retailers accountable.

The Accord was set to expire May 31, but corporate brands agreed to a three-month extension to allow for more time to conclude negotiations on a new binding safety agreement. Global union leaders and human rights activists say the Accord must also be expanded beyond fashion brands.

“While huge strides have been made in the garment industry safety—thanks to the Bangladesh Accord—it is a reminder that without robust and independent systems to enforce safe working conditions, the very worst can happen,” says UNI Global Union General Secretary Christy Hoffman.

Workers say that through their unions, they are able to advocate for safe working conditions without fear of being disciplined or even fired. As with the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse, that killed more than 1,100 garment workers, and the 2012 Tazreen factory fire that killed more than 112 garment workers, those at the Hashem Foods factory did not have a union to help them fight for a safe workplace or ensure children were not employed.

Says Chandon Kumar, BIGUF president: “Government agencies create investigation committees just for show. How come they did not see child labor and insufficient fire protection? We must have the right to form unions, democratic process and the freedom to speak up.”

Jun 16, 2021

Jesmin Begum, a Bangladesh garment worker in her early 30s, died as she and hundreds of others rallied for unpaid wages in one of Dhaka’s Export Processing Zones (EPZs).

A sewing operator, Begum was laid off in January from Lenny Fashion, Ltd., after the factory closed. Although management said it would pay unpaid wages by May, the company never fulfilled its commitment, and workers gathered at the Nabinagar-Chandra highway outside the EPZ June 13 to demand payment.

When the workers at Lenny Fashion Ltd. and another factory that was closed by the same company refused to move from the road after two hours, the police used tear gas, rubber bullets and water cannons to disperse them, and Begum died after she fell fleeing the police violence. Dozens of workers also were injured.

“We are always told that in EPZ factories, BEPZA [Bangladesh Export Processing Zones Authority] enforces workers’ rights properly and vigorously, but BEPZA, as in many other previous cases, has miserably failed here that led to the workers’ protest and death of Jesmin,” says Babul Akhter, president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF)

Worker Rights Abused, EPZs Make Billions

Bangladesh’s eight EPZs received $333.38 million in foreign direct investment and made $7.52 billion from exports in the 2018–2019 fiscal year. Yet Bangladesh workers in EPZs face daunting odds in trying to redress often poor and dangerous factory safety and health conditions, retrieve unpaid wages or end abusive treatment by supervisors because the zones are exempt from the country’s labor laws and workers are prohibited from forming unions.

As a result, they are particularly vulnerable to worker rights abuses. Although they are allowed to organize and form workers welfare associations (WWAs) at their factories, the WWAs do not have the same rights as unions. The ILO Committee of Experts has identified numerous provisions in the WWAs that violate ILO Conventions 87 and 98 on the freedom to form unions an bargain collectively.

The terms and conditions of service for EPZ workers are regulated by BEPZA, essentially eliminating collective bargaining. Labor inspectors are not permitted to inspect factories in the zones and, unlike workers covered under the nation’s labor laws, workers in EPZs do not have the legal right to file a case challenging illegal termination.

In addition, says Akhter, “BEPZA and the employers are systematically dissolving the worker welfare associations in EPZ factories to eliminate any kind of voice of the workers in the workplace.”

With Unions, Workers Advocate for Safe Jobs

Although the government of Bangladesh in 2019 amended the EPZ law with the aim of bringing it more in line with its labor laws and international labor standards, the ILO found the new EPZ Law failed to address the vast majority of these concerns. “Importantly, the new law continues to deny EPZ workers the right to form or join a union,” according to the ILO.

“The EPZ workers must be allowed to exercise their rights to join union of their own choosing, removing the discrimination between the EPZ and non-EPZ workers,” Akhter says.

Without the ability to form unions, garment workers cannot collectively push for safety and health improvements at their workplaces. After more than 1,200 garment workers died in two tragic factory disasters in 2012 and 2013, unions have been a key partner with fashion brands in the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, a landmark agreement that made factories safer for 2 million garment workers. Worker rights advocates are urging extension of the Accord, which expires in three months.

Yet the BEPZA did not allow the Accord to inspect any of the EPZ factories—all the more reason, worker advocates say, garment workers must be able to form union and collectively bargain.

Jun 8, 2021

Worker rights and human rights advocates are urging multinational corporate fashion brands to commit to a binding successor agreement that will continue the pathbreaking work of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, a landmark agreement that made factories safer for 2 million garment workers.

Signed by fashion brands and unions in 2013, the Accord was set apart from previous safety agreements because it was legally binding, providing a key enforcement mechanism for workers and their unions to hold individual brands and retailers accountable. As a result, the Accord “has been the most successful safety program in the contemporary history of apparel supply chains,” according to a recent report by a coalition of worker rights organizations.

It was set to expire May 31, but corporate brands agreed to a three-month extension to allow for more time to conclude negotiations on a new binding safety agreement.

Accord Boosted Safety for Millions of Workers

The Accord “actively engaged with unions to ensure that workers voices are heard in the remediation process to ensure safety in the workplace,” says Rashadul Alam Raju, general secretary of the Bangladesh Independent Garment Union Federation (BIGUF).

“In five years, thousands of fire, building and electrical hazards were fixed in the [ready-made-garment] RMG factories,” he says. “As a result, safety standards were uplifted for millions of workers [and] the country has not witnessed any major accidents or loss of life in the factories inspected by Accord.”

The Accord, which now includes more than 190 brands and covers 1,600 factories, was signed after more than 1,100 garment workers were killed in the April 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh. Voluntary programs, with no legally binding enforcement like the Accord, failed to prevent the Rana Plaza collapse or the tragic Tazreen Factory fire that killed more than 100 Bangladeshi garment workers a few months earlier.

Accord Ensured Workers, Their Unions a Voice

BIGUF General Secretary Rashadul Alam Raju says the Accord ensured safety for millions of workers and must be extended. Courtesy Rashadul Alam Raju

Following a 2020 Bangladesh High Court decision, the Accord’s day-to-day operations were handed over to the Ready-Made Garment Sustainability Council (RSC), comprised of brands, factory owners and global and local unions. But the RSC is not legally binding and, “for all intent and purposes, is not going to bring about any real change in the factory conditions,” says Raju.

Crucially, the Accord supported an environment in which workers’ voices could be heard through collective bargaining between unions and employers, enabling unions to protect workers’ safety and ensuring they woud not be targeted by managers for speaking out about their workplace rights.

“The Accord was very much proactive in engaging with the unions in its work to ensure safety for the workers,” says Raju. “This also ensured protection to the workers and unions from being victimized by the employers. But such protection with RSC is virtually non-existent.”

Bangladesh garment workers, primarily women who often are subject to brutal verbal and even physical violence for supporting unionization, were able to form dozens of unions in the wake of the Accord, with tens of thousands achieving first-ever rights on the job.

Raju and other Bangladesh union leaders say the Accord’s signatory brands must agree to a new binding safety agreement that ensures safe work, remains individually enforceable upon brands, keeps an independent secretariat in place that oversees the brands’ compliance and allows for expansion to other countries.

Although brands committed in January 2020 to negotiate a new binding agreement with the option to expand to other countries, they since have offered only a watered-down version of the Accord.

A renewed agreement is urgently needed, union leaders say, because much work still must be done to ensure factory safety in Bangladesh and around the world. A renewed agreement offers the possibility of expanding factory safety and health to other countries, where recent disasters underscore the need to address life-threatening work environments.

The bottom line, says Raju, is that unions must be part of any new agreement, “but it has to be legally enforceable.”

Jun 1, 2021

Half or more workers in key Cambodian industries were suspended for three or four months, and most were unable to support themselves on government aid during the pandemic, according to a new study that put hard data to the suffering of the country’s low-wage workers.

Some 53 percent of those working in tourism were suspended for an average 15 weeks, and 40 percent of workers in Cambodia’s garment and footwear industries were suspended for an average of 11 weeks, according to a survey of 1,525 workers by the Center for Policy Studies. Solidarity Center and The Asia Foundation supported the research, which reports results from July and August 2020. (See the full survey.)

Women workers in Cambodia worked more and were still paid less than men during the pandemic. Source: CPS/Solidarity Center/Ponlok Chomnes

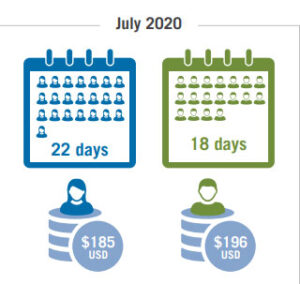

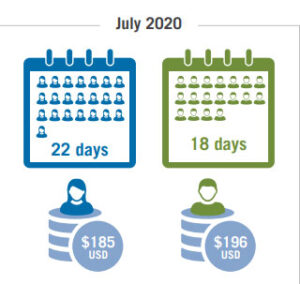

Women comprise the majority of workers surveyed and are the majority of 800,000 workers in the country’s garment and footwear industries. Before the pandemic, women were typically paid less than men. Yet, even when they returned to work in July 2020, they reported being paid less than men even though they worked more days than men.

All workers who returned to the job by July 2020 on average were employed for fewer hours and earned less than in July 2019.

COVID-19 an Excuse to Exploit Workers

Although many businesses were forced to temporarily suspend operations or shutter permanently during Cambodia’s first wave of COVID-19, some employers took advantage of the pandemic to lay off workers, union leaders say.

Further, hospitality and garment workers who returned to, or remained on the job, were not provided adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) or measures to ensure their safety, according to union leaders in Cambodia. Unions have been organizing to hold employers to account, negotiating for better protection measures.

Government Support Helpful, Not Sufficient

To assist garment and tourism workers during the country’s first wave of COVID-19, the Cambodian government launched several programs, including financial support for workers suspended from the job and a skills improvement training program. But workers interviewed for the survey said the suspension payments, which ranged $40 to $70 per month, were not sufficient to cover the roughly $69 they needed for basic monthly food expenditures.

Half of those surveyed say the suspension allowance was their only income, and more than 50 percent said they could not afford to send remittances to their family as a result of pandemic-related losses. Between 40 percent and 60 percent of workers surveyed say they took on debt to survive.

The government announced in July 2020 that businesses closed during COVID-19 were not required to pay workers hardship or layoff wages. Tourism sector operations also were not required to contribute the $30 per month toward the suspension payments. The government provided $40 per month.

Urgent Action Needed for New Pandemic Wave

Since February, Cambodia has experienced its worst COVID-19 outbreak, which has led to a deepening crisis for workers as many major cities and several provinces have been in strict lockdown.

During the pandemic, workers in many industries have been left out of public social protection programs, such as health coverage, and the survey recommends extension of these benefits for the most vulnerable.

The survey also recommends expanding skills improvement training programs and funding opportunities for temporary jobs.

Without such support, garment workers like Eang Malea are returning to their factories despite the risk of contracting COVID-19.

“I need to pay rent, utilities and debts, ” Malea, 26, said. “I worry that I will get infected by going to work without being vaccinated, but I don’t really have a choice.”

May 21, 2021

بالعربية

Agricultural workers in Jordan for the first time have fundamental protections on the job, including guarantees for safe and decent working conditions, following a two-year campaign by the Agricultural Workers Union in Jordan and its allies that resulted in passage of a historic regulation covering the agricultural sector.

“This is quite a landmark in Jordan. It’s the first time this type of legislation has passed,” says Hamada Abu Nijmeh, director of the Jordan-based Workers’ House for Studies. Under the regulation, any provision not mentioned falls under purview of national labor code.

The law applies to all workplaces that employ more than three agricultural workers, who now will receive 14 days annual paid leave and 14 days paid sick leave (or more, in cases of serious illness). Women are guaranteed 10 weeks paid maternity leave and there are now first-ever provisions for overtime pay. Significantly, the legislation also covers migrant agricultural workers, who frequently are not protected by countries’ labor laws.

COVID-19 Makes Visible Essential Workers

Agricultural workers in Jordan were key to developing the new labor regulation improving wages and working conditions.

Prior to passage of the regulation this month, there were no mandated safety inspections of farming facilities, leaving workers vulnerable to dangerous and unhealthy working conditions, such as exposure to poisonous pesticides. Agricultural workers, most of whom do not have formal labor contracts and are part of the country’s vast informal economy, were paid extremely low wages with no health insurance or other social protections. Working long hours, they were not guaranteed a day off during the week and not paid overtime. They were denied the freedom to form unions—the Agricultural Workers Union is not recognized by the government. Migrant workers still do not have the right to form unions under the new law.

Although a labor law covering agricultural workers was passed in 2008, the government never moved to put it in place, says Mithqal Zinati, union president. But as the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted essential workers like those who literally feed the world, the government became more receptive to the union’s campaign to ensure decent working conditions in the vineyards and fields.

“The agricultural sector is the food basket, the key source of stability that needs to be given priority to contribute to the stability of Jordanian state itself,” says Abu Nijmeh. “Part and parcel of that is to provide protection of workers. We told [the government] if you want to see this sector successful, you need to provide its protection.”

Abu Nijmeh and Zinati spoke with the Solidarity Center through interpreters.

Danger on the Job and Getting to Work

For Jordan’s 210,000 agricultural workers, more than half of whom are women, the day begins before dawn as they rush to meet the crowded trucks that transport them to the fields in the fertile Jordan Valley. Picking cucumbers, melons and okra in summer, citrus fruits in winter, the workers also weed fields, install water pipes and spray crops. They often are denied breaks, even as they work in the burning sun and harsh cold, and women have no access to toilets, leaving many with serious kidney issues and other illnesses, says Zinati. Just this week, a worker died of sun stroke in the fields, Zinati says.

Before they even arrive at the farms, women are subject to unsafe conditions on the packed vehicles they must use to get to work. Some 86 percent say they were involved in an accident on the commute, and 41percent say they are subjected to sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence during the journey, according to a study by SADAQA, a nonprofit organization championing the rights of women in Jordan. SADAQA produced the study, “Women Agricultural Workers in the Jordan Valley: Conditions of Work and Commuting Experiences and Challenges,” with Solidarity Center support.

Twenty or more workers are packed in a van licensed for five passengers, sitting on top of each other and in the luggage compartment, says Zinati. The vans take back roads to avoid police because they are not licensed, or licensed only to transport crops and other goods, and workers frequently suffer injuries as the overcrowded vehicles crash on the rough roads. Because most women work in shifts, they must commute two times per day, says Randa Naffa, SADAQA co-founder, speaking through a translator.

Together with the Solidarity Center, SADAQA produced a video on the outcome of the study documenting the hazards women face commuting to the fields. SADAQA, part of the Alliance to End Gender-Based Violence and Harassment in the World of Work, is using the video to campaign for regulations covering agricultural transport. The alliance is pushing the government to ratify International Labor Organization Convention 190 on ending gender-based violence and harassment at work. Convention 190 makes clear that employers and governments must take measures to ensure workers are safe on their work commute as well as in the physical workspace.

Worker Involvement Key to New Regulation

Agricultural workers were key to designing the new regulation. Beginning in 2019, leaders at the union and the Workers’ House met with workers on the farms to determine their needs and priorities. With worker input forming the basis of the draft regulation, campaign leaders applied labor regulations and human rights provisions from international standards and legislation from other countries to create a model regulation. The Workers’ House and the Solidarity Center then organized a meeting of agricultural workers to discuss the draft again and plan campaign steps, including social media outreach.

They formed a coalition with civil society organizations to launch an advocacy campaign that included petitions and public statements to the Ministry of Labor and other government officials which, along with social media outreach to mobilize public support, was key to moving the government to pass the regulation protecting these essential workers.

“I heard from the Ministry of Labor they said they were listening to, keeping abreast of what was spread in the media,” says Abu Nijmeh.

“The regulation that has just been promulgated, we hope it will protect female workers in this sector and it is the opportunity to create the political will to recognize the importance of women’s contributions to the agriculture sector and the importance of women’s contributions to other informal sectors,” says Naffa.

Worker Education Essential for Success

Abu Nijmeh, Zinati and Naffa all emphasized the need to ensure implementation and enforcement of the new regulation, especially workplace inspection, safety and health and child labor. Under the new regulation, children younger than age 16 cannot work in agriculture and those between ages 16 and 18 can only be engaged in non-hazardous work.

The regulation “shall never be enforced without pushing,” says Naffa. “We need to lobby more, engage in campaigns, reach out to the Labor Ministry, the Transport Ministry.” Key to its success is widespread education of agricultural workers about their rights, says Zinati.

A long-time union organizer who began by unionizing court workers in Beirut, Lebanon, Zinati says union committees are now set up in every village, and literacy classes and other education opportunities are offered so workers can better champion their rights.

“If I see people who are done an injustice, who are oppressed, the only way for them to gain their rights is for them to unite,” he says. “This legislation opens the horizon so workers can play a bigger role in pushing their rights,” he says.