Jun 15, 2020

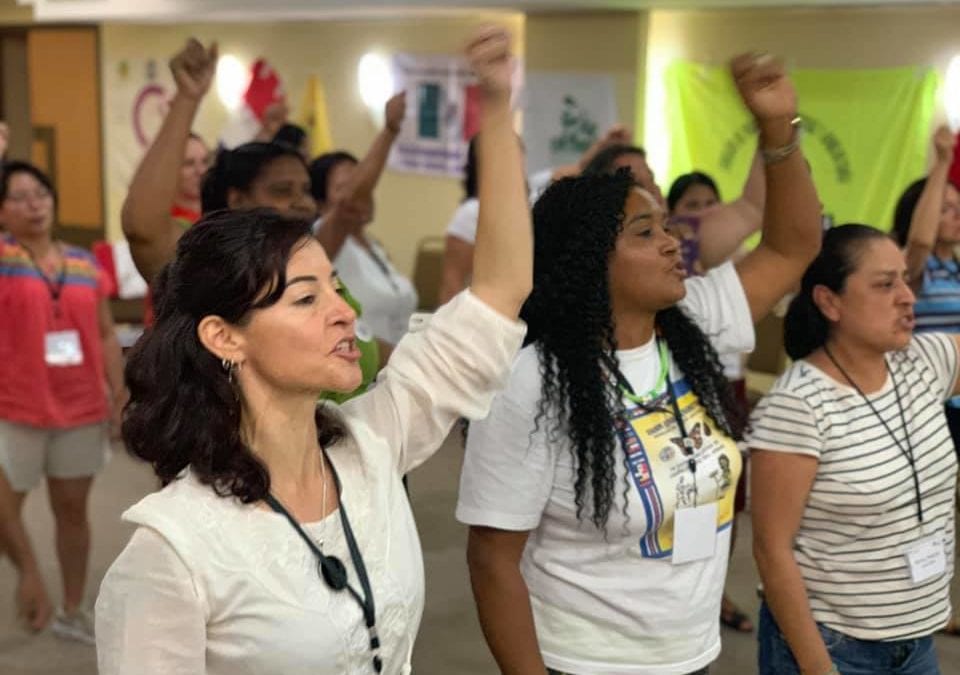

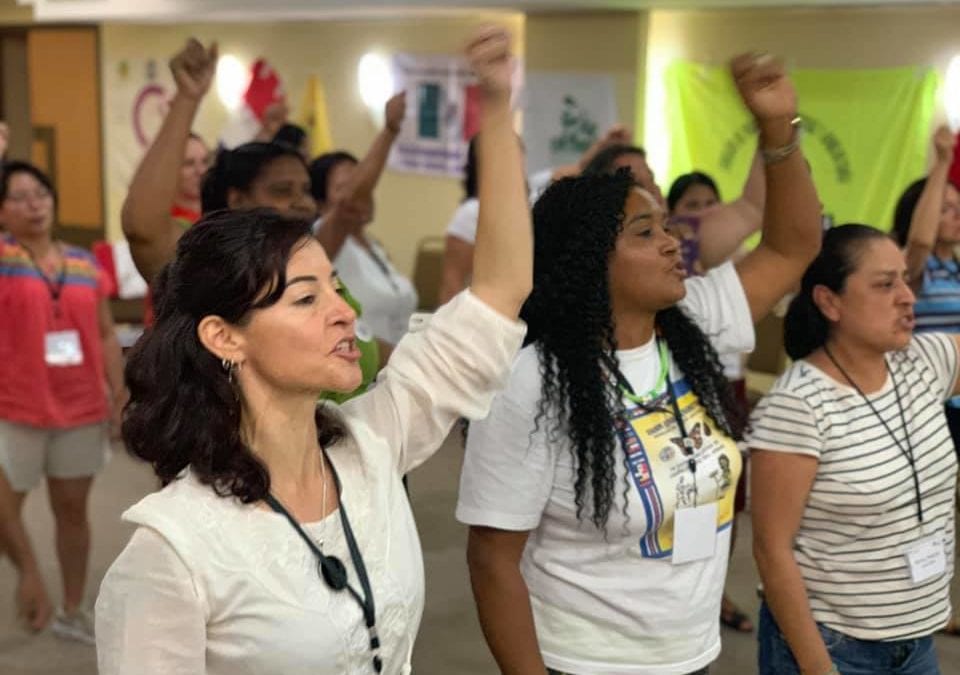

Domestic workers—at great risk during the pandemic crisis—are mobilizing to secure rapid relief and protection says the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF). This International Domestic Workers Day, more than 60 million of the world’s estimated 67 million domestic workers, most of whom are women of color working in the informal economy, are facing the pandemic without the social supports and labor law protections afforded to workers in formal employment. And, during a period of heightened infection risk, tens of thousands of migrant domestic workers are being forced to live in their employers’ homes, housed in crowded detention camps or have been sent home where there are no jobs to sustain them or their families.

The health and economic risks to domestic workers during the pandemic and compulsory national lockdowns are high. At the margins of society in many countries, most domestic workers are excluded from national labor law protections that require employers to provide paid sick leave and mitigate workplace infection risks through provision of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and appropriate social-distancing measures. And, if they get sick, many domestic workers cannot access national health insurance schemes.

“Domestic workers are among those most exposed to the risks of contracting COVID-19. They use public transport, are in regular contact with others… and don’t have the option of working from home, especially daily maids,” says Brazil’s national union of domestic workers, FENETRAD.

Without adequate personal savings due to poverty wages, many domestic workers and their families are suffering food insecurity because of income interruption or job loss.

“We can’t have many domestic workers left out in the cold,” says Myrtle Witbooi, founding member and first president of IDWF, and general secretary of the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union (SADSAWU).

“Let us shout out to the world: We are workers!” she says.

Domestic workers have long shared their experiences with the Solidarity Center, detailing their long working hours, poverty wages and violence and sexual abuse. During the pandemic, additional sources of economic peril and health risks are being reported, including:

- In Mexico, where 2.2 million women are domestic workers, most of them are being dismissed without compensation. In a recent survey of domestic workers, the national domestic workers union SINACTRAHO found that 43 percent of those surveyed suffered a chronic condition like diabetes or hypertension, increasing their vulnerability to COVID-19.

- The United Domestic Workers of South Africa says their members report that some employers refused to pay wages during the country’s compulsory lockdown unless staff agreed to shelter in place with their employer, and that domestic workers who could not report to work were not paid.

- In Asia, women performing care work were excluded when countries launched COVID-19 responses and stimulus packages, says Oxfam.

- In the Latin American region, where millions of people who labor in informal jobs rely on each day’s income to meet that day’s needs, the pandemic lockdown is causing an economic and social crisis.

- Globally, unemployment has become as threatening as the virus itself for the world’s domestic workers, reported the ILO in May.

Meanwhile, migrant domestic workers—who often leave behind their own children to care for others to support their own families back home—are in peril. Some are being sent home without pay, some are subject to wage theft. Others are being quarantined by the thousands in dangerously crowded conditions or in lockdown in countries where they do not speak the language and have little access to health care, local pandemic relief or justice. For example:

- Thousands of Ethiopian domestic workers are stranded in Lebanon by the coronavirus crisis.

- At least one-third of the 75,000 migrant domestic in Jordan had lost their incomes and, in some cases, their jobs only one month into the pandemic.

- For millions of Asian and African migrant domestic workers in the Middle East, governments restrictions on movement to counter the spread of COVID-19 increased the risk of abuse, reports Human Rights Watch.

- Several Gulf states are demanding that India and other South Asian countries take back hundreds of thousands of their citizens. Some 22,900 people were repatriated from the UAE by late April, many without receiving wages for work already performed.

On June 16, International Domestic Workers Day, we honor the majority women who perform vital care work for others. Every day, and especially during the pandemic, the Solidarity Center is committed to supporting the organizations that are helping domestic workers attain safe and healthy workplaces, family-supporting wages, dignity on the job and greater equity at work and in their community.

“International Domestic Workers Day is a great opportunity to talk about power and resistance, and how we survive now and build tomorrow,” says Solidarity Center Executive Director, Shawna Bader-Blau, who applauds actions by all organizations dedicated to supporting and protecting domestic workers during the pandemic. These include:

- Domestic workers who are leaning into organizing and advocacy efforts during the pandemic, including in Peru, where they won the right to a minimum wage and written contracts by challenging the constitutionality of failing to implement the ILO domestic workers convention after ratification; in the Dominican Republic, where they mobilized to register 20,000 domestic workers into the social security system and lobbied for their inclusion in government aid, gaining new members in the process; in Brazil, where they successfully fought to remove domestic workers from the list of “essential workers” to limit their exposure to COVID-19 because of their limited safety net.

- In Bangladesh, BOMSA, a migrant rights nongovernmental organization (NGO), is creating and distributing COVID-19 awareness-raising leaflets specifically for migrant domestic workers returning to Bangladesh from abroad. Members are distributing soap, disinfectant and other cleaning supplies, and encouraging workers to maintain social distance. Another migrant rights NGO, WARBE-DF, is distributing COVID-19 awareness-raising leaflets to returned migrant workers and their communities. And as thousands of migrant workers return, the organization is engaging in local government coronavirus response committees to ensure inclusion of migrant-specific responses. Both are longtime Solidarity Center partners.

- Also in Bangladesh, in Konbari area—where garment workers who are internal migrants are not eligible for relief aid as it relies on voting lists for relief distribution—the local Solidarity Center-supported worker community center is connecting with local government officials and has provided nearly 200 names for relief, and is fielding more calls from internal migrant workers seeking assistance.

- In Brazil, which has more domestic workers than any other country—over 7 million—the National Federation of Domestic Workers (FENETRAD) and Themis (Gender, Justice and Human Rights) started a campaign calling for domestic workers to be suspended with pay while the risk of infection continues, or to be given the tools to protect against risk, including masks and hand-sanitizing gel.

- Also in Brazil, FENATRAD is providing legal and other advice by phone to domestic workers and delivering relief packages of food, medicines and protective gear, including masks, clothing, soap and hand sanitizer, to union members and their families.

- In the Dominican Republic, three organizations representing domestic workers successfully advocated with the Ministry of Labor for domestic workers’ to be included in the country’s COVID-19 relief program.

- In Mexico, to raise awareness and make the sector more visible, SINACTRAHO collected WhatsApp domestic worker audio messages about their experiences during the crisis for sharing on a podcast.

- The Alliance Against Violence & Harassment in Jordan, a Solidarity Center partner, is urging the government to grant assistance to migrant workers, who have little or no pay but cannot return to their country. The Domestic Workers’ Solidarity Network in Jordan shares information on COVID-19 and its impact on workers in multiple languages on its Facebook page

- The Kuwait Trade Union Federation urged the government to address the basic needs of Sri Lankan migrant workers, many of whom were domestic workers trapped in Kuwait after Sri Lanka closed its borders on March 19. Workers were eventually housed in 12 shelters while travel arrangements home were made.

- In Qatar, Solidarity Center partners Migrant-Rights.org and IDWF in April helped launch an SMS messaging service in 12 languages to provide tips to migrant domestic workers on COVID-19 and how to protect their rights.

- In South Africa—where many domestic workers suffer deaths and crippling injuries without compensation because they are excluded from the country’s occupational injuries and diseases act (“COIDA”), according to a recent Solidarity Center report—trade unions are demanding that employers provide their domestic workers with adequate PPE.

The Solidarity Center has joined its partners, the Women in Migration Network (WIMN) and a coalition led by the Migrant Forum in Asia, in urging governments and employers to uphold the rights of migrant workers, including migrant domestic workers.

Without urgent action to provide relief to workers in informal employment, including those providing domestic work, quarantine threatens to increase relative poverty levels in low-income countries by as much as 56 percentage points according to a new brief from the UN’s International Labor Organization (ILO).

Jun 3, 2020

Trade unions around the world are raising the alarm as some governments and employers during the coronavirus pandemic are failing to meet their obligation to protect workers’ health and safety in violation of international agreements and hard-fought-for national legislative frameworks that provide workers with the means to secure safer and healthier workplaces.

Workers in health care and other sectors are demanding that governments and employers take steps to protect workers, including recognition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as an occupational hazard and COVID-19 as an occupational disease. The ITUC, on UN World Day for Safety and Health at Work, said that recognition will ensure for workers the right to representation and occupational safety and health (OSH) rights and the application of agreed-upon measures to reduce risk, including the right to refuse to work under unsafe working conditions.

Healthcare workers are particularly imperiled on the front lines of the COVID-19 outbreak, given their vulnerability to pathogen exposure, long working hours, psychological distress, fatigue, occupational burnout, stigma and physical and psychological violence. On April 28, UN World Day for Safety and Health at Work, the World Health Organization (WHO) called upon governments, employers and the global community to take urgent measures to strengthen their capacity to protect the health and safety of health workers and emergency responders, and to respect workers’ right to decent working conditions especially during the pandemic.

“We just want to be able to do our job safely,’ says a Hussein University hospital doctor in Cairo, Egypt.

Amid continuing shortages of protective equipment, at least 90,000 healthcare workers worldwide are believed to have been infected with COVID-19, and perhaps twice that, said the International Council of Nurses (ICN) earlier this month. Health workers around the world are at risk from preventable infections and other job-related dangers during the crisis. For example:

- Algeria doctor Wafa Boudissa—denied early maternity leave three times by hospital management in contradiction of a presidential decree protecting pregnant women–died at age 28 last month, at eight months pregnant.

- In Brazil, nurses are dying as the pandemic overwhelms hospital, even while the government downplays the contagion.

- Medical staff in Cameroon are asking for additional security at hospitals following a series of attacks by people upset that they or their loved ones were diagnosed with the coronavirus.

- In the impoverished North Caucasus republic Daghestan, more than 40 healthcare workers are reportedly dead of COVID-19, although officials claim they did not all die from coronavirus.

- Medical workers in Egypt are describing dangerous workplaces in which personal protective equipment (PPE) is in short supply and too few COVID-19 tests are available to workers and patients. About 13 percent of those infected in Egypt are medical professionals, according to the UN’s World Health Organization (WHO). 19 doctors have reportedly died so far from the disease.

- Doctors, nurses and laboratory technicians among others in Lesotho deemed themselves unable to work following multiple failed attempts to engage authorities on how to obtain protective gear, provide payments for health care workers contracting COVID-19 and providing a risk allowance for those treating COVID-19 patients.

- In Mexico, health care workers are facing violent attacks by members of the public who fear contagion as well as by family members angered by news of a loved one’s infection or COVID-19–related death. Medical workers have been chased from their homes, doused in bleach and beaten. Following false reports of intentional transmission of the coronavirus by medical personnel, citizens blocked highways and roads in the municipalities of Ciudad Hidalgo, Tuxpan and Zitácuaro.

- 27 doctors and 20 nurses are reported dead in Indonesia. With 3,293 infections and 280 deaths, Indonesia has the highest death toll in Asia after China, although health experts fear it could be much higher.

- In Kaduna State, Nigeria, government threatened mass dismissals of health workers who choose not to report for work during the pandemic, even though they report inadequate PPE and the government recently cut their salaries by 25 percent.

- In Pakistan, after police arrested more than 50 doctors demanding PPE, dozens of doctors and nurses went on a hunger strike to demand safety equipment and protest the infection of 150 medical workers and deaths of several, including that of a 26-year-old doctor who had just begun his medical career.

- Medical workers in Russia are dying 16 times more often than in countries with comparable coronavirus outbreaks; health care workers there comprise 7 percent of COVID-19 fatalities, according to Russian media outlet Mediazona; medical workers’ own list numbers healthcare-worker fatalities at 240.

Not only those working in the health sector are at risk, say trade unions, given that many of the world’s workers must continue to physically report for work because they do not have savings to sustain a lengthy quarantine, they do not want to lose their jobs or their work has been categorized essential. For example:

- In Bangladesh, against Ministry of Health advice and during the country’s coronavirus lockdown, tens of thousands of garment workers returned in late April from far-flung homes to crowded, factory-based dormitories to jobs in factories that mostly lack adequate infection control measures. In an attempt to deliver pending orders to global clothing brands, about half of Bangladesh’s 4,000 garment factories have reopened.

- After exposure to a single infected worker in Ghana, 533 factory workers at a fish-processing plant in the port city of Tema tested positive for the coronavirus, representing more than 11 percent of Ghana’s total COVID-19 infections to date.

- More than 200 textile workers at an export-focused plant in Guatemala tested positive last week for the novel coronavirus, with more results pending; testing was forced on the employer after reports surfaced that infected workers were continuing to work and the company was not taking protective measures.

- At some apparel factories in Honduras workers were expected to continue to work in violation of the government’s lockdown order, including at a plant where 2,400 workers make T-shirts and sweatshirts for export.

- Mexico oil company Pemex and the country’s Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) together had 1,245 confirmed cases by mid-May. Pemex alone reported 1,092 cases and 141 deaths as of last week: an average rate of infection of 20.7 people per day and 2.5 daily deaths.

- A number of firms in Mexico continue to produce goods for the U.S. market despite coronavirus lockdown rules, putting their workers in grave danger of contracting COVID-19.

- In South Africa, which has the most cases of coronavirus in Africa, an outbreak closed Mponeng gold mine after 164 cases of coronavirus were detected there last week despite working at 50 percent capacity. The South African Human Rights Commission (the SAHRC) warned employers that failure to failure to implement precautionary measures to protect workers from contracting COVID-19 would constitute a human rights violation under the South African constitution, and be pursued as such by the Commission with other statutory regulatory bodies.

- Worldwide, migrant workers clustered in low-wage, informal sector jobs in high-density living conditions or engaged in care work in close quarters with their employers are succumbing in higher numbers to infection as compared to local populations. Last month, Saudi Arabia sent home nearly 3,000 of the estimated 200,000 Ethiopians living there before the United Nations called for a halt.

There were at least 5,546,000 cases and 347,000 deaths reported in at least 180 countries worldwide in the COVID-19 pandemic as of May 26, 2020, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University.

May 18, 2020

Among the world’s most vulnerable workers are those marginalized within their economies and societies, namely the women and labor migrants who predominate in the informal economy, where they perform valuable work in low-wage jobs as janitors, domestic workers, agricultural workers, home healthcare workers, market vendors, day laborers and others. Today, many of these workers are on the coronavirus front lines, risking their health without benefit of paid sick leave, COVID-19 relief programs or personal savings. Others are working where they can, if they can, to survive.

Although more than 2 billion workers globally make their living in the informal economy and can create up to half of a country’s GDP, they have limited power to advocate for living wages and safe and secure work, and never more so than during the current pandemic when informal-sector workers are disproportionately falling through the cracks. Due to the failure of governments to build systems of universal social protection, the world is facing the pandemic with 70 percent of all people lacking a safety net, says International Confederation of Trade Unions (ITUC) General Secretary Sharan Burrow. Also, despite their vast numbers—61 percent of the world’s workers work in the informal economy and, in developing countries, that number can rise to 90 percent of a country’s workforce—informal-sector workers are consistently overlooked by legislators and policy makers for economic assistance and legal protections during the current crisis.

A new brief from the UN’s International Labor Organization (ILO) warns that workers earning their livelihoods in the informal economy in 2020 are being forced “to die from hunger or from the virus” and offers a raft of immediate, medium- and long-term recommendations for governments and employers’ organizations to address the crisis. Without urgent action, quarantine threatens to increase relative poverty levels in low-income countries by as much as 56 percentage points, according to the brief.

The far-reaching effects of the coronavirus pandemic have expanded global calls for a new social contract by worker rights organizations that are championing a “build back better” campaign as well as by some businesses that recognize the unsustainability of economic and social structures in which workers absorb the burdens of our economies but not the benefits.

Unions and worker rights activists are stepping into the breach, giving voice to workers’ struggles during lockdown, providing relief where resources allow and banding together to urge governments to provide financial and other social support for informally employed workers, as well as protection from harassment.

- The Central Organization of Trade Unions-Kenya (COTU-K) distributed protective gear, such as masks, gloves, soap and hand sanitizer to workers before shops were closed, and has met with the Kenyan government to lobby for support for informal workers, who comprise some 80 percent of the workforce.

- In Zimbabwe, informal economy association ZCIEA is giving voice to vendors’ struggle for survival under quarantine and advocating for their right to operate. In Harare, even though markets are legally open and deemed essential for citizens to secure food, ZCIEA Chitungwiza Territorial President Ratidzo Mfanechiya says that ZCIEA has had to intervene with the town manager, town council and local police to protect Jambanja market vendors’ right to operate free of harassment and forced removal during the five-week lockdown. She is also speaking out against gender-based violence, given that many women are reporting incidents of abuse while trapped at home with partners during lockdown.

- The Alliance Against Violence & Harassment in Jordan, a Solidarity Center partner, is urging the government to grant assistance to migrant workers, who have little or no pay but cannot return to their country of origin. The Alliance also asks for safety gear for migrant workers still on the job. The domestic workers solidarity network in Jordan shares information on COVID-19 and its impact on workers in multiple languages on its Facebook page.

- Leaders of multiple women’s worker rights movements banded together in May to make a joint call on the world’s governments to collaborate at all levels with domestic workers, street vendors, waste pickers and home-based workers during the COVID-19 crisis so that some of the world’s most important systems traditionally propped up by informally-employed women—including food supply, the care economy and waste management—are preserved.

- In India, where an estimated 415 million workers, or 90 percent of the country’s total workforce, toiled in informal-sector jobs in 2017–18, trade unions lobbied Labor Minister Santosh Gangawar for income support and eviction support for more than 40 categories of informal workers hit by the coronavirus pandemic.

In 2018, the workforce in informal employment in Africa was 86 percent; in Asia and the Pacific and the Arab states, 70 percent; in the Americas, 40 percent; and in Europe and Central Asia, 25 percent.

May 15, 2020

As the COVID-19 crisis deepens in Ukraine and scandals are alleged regarding state procurement of personal protective equipment (PPE), worker rights activists are leveraging trade unions’ collective power to advocate for better pay and conditions for working people and help provide emergency relief during quarantine. The country’s trade unions are persisting in delivering help and calling out injustices—no small task given that Ukraine last year was awarded the worst labor rights score in Central and Eastern Europe.

Worker-initiated advocacy measures include:

- Civil society activists and the five major trade unions of Ukraine that represent 7 million members continue to resist proposed changes to the country’s labor law, which, in violation of international labor law, would allow employers to fire workers for any reason and drastically reduce overtime pay.

- Ukraine’s construction workers’ union began a collective bargaining process to minimize the negative effects of the pandemic on the construction sector and initiated a criminal case against construction company Prosco for wage theft.

- Trade union activists are speaking out on behalf of an emerging small entrepreneurs’ movement that is protesting disproportionate government support for larger, mostly oligarchy-owned, businesses during the lock down, and demanding equal support for small and micro-businesses, including small-scale farms.

- Workers at Ukraine’s postal and delivery service Nova Poshta successfully lobbied their employer to provide all 30,000 Nova Poshta employees with PPE when needed and preserve the wages and benefits of those required to stop working during quarantine.

- The Federation of Trade Unions of Ukraine, FPU, on April 29 provided a live-streamed question-and-answer forum for labor leaders from Kharkiv, Kryvyi Rih, Poltava, Lviv, Zaporizzhya, Ternopil, and Kamyanske to consult with FPU experts about worker’s legal rights under Ukraine’s labor law during the pandemic, and to share their members’ most commonly reported violations—including overwork, employer pressure to take unpaid leave and issues around telework.

- Leaders of the Confederation of Free Trade Unions of Ukraine, KVPU, on April 30 held a live-streamed conference with representatives of the medical workers’ union, rail workers’ union, independent unions of Donetsk region, the LEONI Wiring Systems union and others to catalog and discuss challenges reported by workers at home and on the job due to the pandemic—including job losses at shuttered mines in the Donetsk region, lack of PPE for medical workers and the uneven impact of quarantine on women.

- Trade unions in the Dnipro region successfully lobbied employers, local government and volunteers for increased support of medical workers at the frontline of the COVID-19 fight.

- Tower crane operators in Lviv held a wildcat strike, refusing to work until they receive their February and March wages and employer-provided PPE.

- Following an appeal from workers at the Kremenchuk machine-building plant, the local government in Poltava province allocated an additional $14,600 for medical worker needs, including face masks.

Worker-initiated relief measures include:

- Labor Initiatives (LI), a Solidarity Center-supported Ukrainian non-profit organization, is providing legal assistance to workers by distributing COVID-related information through its phone hotline, website, Facebook page and other social media. LI’s hotline provided some 100 consultations during the country’s first week of quarantine; its website FAQ on labor rights during the quarantine was viewed more than 60,000 times in March.

- The Trade Union of Healthcare Workers of Ukraine (HWUU) launched a hotline to collect and respond to emergencies reported by frontline healthcare workers, which include inadequate PPE and excessive workloads due to layoffs.

- Trade union members at Nova Poshta launched a COVID-19 email help line, provided disinfectants and children’s educational materials to all its members, and distributed 1,000 face mask vouchers to members deemed most at risk from COVID-19.

- The trade union representing workers employed by the Naftogaz state energy enterprise collected $300,000 for local healthcare worker needs, which was distributed to workers at 21 hospitals and 26 urgent-care centers.

- Also to support medical workers, the trade union representing workers employed by Ukraine’s Rivne Department of Culture collected $2,000 while the Rivne province union solidarity fund donated $50,000.

- Members of the trade union representing workers at oil-transporting company Ukrtransnafta distributed 2,256 food baskets to elders in need at a cost of $31,500.

- Unions in Pavlograd purchased 20 medical ventilators for hospitals in Pavlograd, Pershotravensk and Ternivka, and purchased $112,000 of PPE.

- KVPU-affiliated trade union activists at Antonov aircraft company helped ensure the safety of workers who are transporting medical equipment and PPE globally, including to COVID-19 hotspots.

- The trade union representing nuclear sector workers in Ukraine donated its entire reserve fund of $38,500 toward the purchase of PPE and relief for medical workers.

- Nuclear sector workers in Mykolaiv province collected $7,300 for medical workers at Yuzhnoukrayinsk hospital.

- The local chapter of the industrial workers’ union in the city of Kryvyi Rih organized self-manufacture of face masks for its members and others, producing more than 1,000 masks through March.

May 9, 2020

The parliament of the Bosnian Federation entity has proposed a labor law amendment that, if enacted, would give employers the authority in any future state of emergency to enact mass layoffs, slash hours and cut many workers’ pay to the minimum wage.

The labor federation in the entity, SSSBiH, adamantly opposes the proposed amendments because they clearly favor employers at the expense of workers during any future state of emergency.

If the text of the draft law is sent to parliamentary procedure, the labor federation said it would “take all necessary actions” to prevent its adoption.

The labor federation’s statement included the following summarized points:

- The proposed amendments were written behind closed doors without worker consultation.

- The claim that workers’ rights are protected by the obligation for employers to consult with unions is frivolous.

- The text of the proposed amendments envisages reduction of worker’s wages by the employer’s unilateral decision during a state of emergency.

- The amendments include provisions on paid leave without defined compensation, forced unpaid leave and at-will firings by employers, but do not provide increased compensation for essential workers who are exposed to infection during a pandemic.

“In the recent emergency, essential workers, including those in health care, were required to work without sufficient protection for their health. Many became sick on the job, and some died. Parliament should concentrate on setting standards all employers must meet in any future emergency to protect front-line workers, rather than enabling employers to lay off staff, cut pay and slash hours.” says Solidarity Center Europe/Central Asia Director Rudy Porter.

The federation’s full response to the proposed labor law amendments can be found here.