Apr 23, 2019

Six years ago, the preventable Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh killed 1,134 garment workers in the world’s worst garment industry disaster. Corporate greed, inadequate labor and building code enforcement, and worker exploitation all contributed to the April 24, 2013, tragedy, which spurred efforts to improve factory safety and support workers seeking a voice on the job.

Nurunnahar mourns the loss of her daughter who died in the Rana Plaza collapse. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Many survivors still face unemployment and poverty because they are too injured to work, according to an Action Aid survey. Months before Rana Plaza collapsed, a fire at Tazreen Fashions factory killed more than 112 workers, part of a pattern of dangerous conditions and deadly risks garments workers face each day in Bangladesh.

Following Rana Plaza, Bangladesh has seen important international and domestic efforts to address fire and building structure risks and improve the labor conditions that hinder workers from reporting dangerous working conditions and violations, and exercising their labor rights. Initiatives like the Bangladesh Accord for Fire and Building Safety, a binding agreement involving fashion brands, unions and the government that helped make many garment factories safer, fueled a rise in union organizing.

And through worker education, like the Solidarity Center’s Fire and Building Safety program, garment workers are boosting their capacity to identify safety and health problems at the workplace and learn about their right to join together to ensure safe workplaces by taking collective action to resolve problems.

6,000 Garment Workers in Solidarity Center Fire Safety Trainings

More than 6,000 Bangladesh garment workers have participated in Solidarity Center safety programs in recent years, including Shilpi Akter, who has worked in the garment industry for more than 10 years.

Some 6,000 Bangladesh garment workers have taken part in Solidarity Center fire safety trainings. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

“Before the Rana Plaza incident, there were no sprinklers, fire doors or emergency lights in our factory,” she says. “I had no idea what fire or health and safety at work meant, neither did we have any trade unions or safety committees.

“Through Solidarity Center’s fire safety training, I learned how to use a fire extinguisher, how to be safe from the fumes during a fire accident, and that I must not keep the clothes I stitch near the heated motor of the machine. This knowledge was unknown to me even a few years back.”

Bilkis Begum, a garment worker and a union president, says before Rana Plaza, “we handled the toxic chemicals without any precaution and had no idea on what to do in case of a fire accident except to run.”

Mohammed Ronju paints the incident more starkly. “There would be no Rana Plaza if it had a union,”’ says Ronju, who has worked in the garment industry for 15 years. If workers had a union, they “would not go inside the building when they sensed trouble. They would have strongly resisted the pressure from management to go inside a building about to collapse.” The day before the Rana Plaza disaster, building engineers declared the structure unsafe. Yet managers threatened to withhold wages if workers did not show up for work the day Rana Plaza collapsed.

‘No More Rana Plazas’

Each year, tens of thousands of Bangladesh workers rally on the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster to demand safe working conditions. Photo: Solidarity Center/Sifat Sharmin Amita

The Rana Plaza tragedy prompted international efforts, through the Accord and other mechanisms, to ensure dangerous garment factories were closed or repaired and safety measures instituted. As a result, factory compliance with fire and building safety codes has improved. Yet much more work remains to be done to ensure full compliance with basic fire and building safety and occupational health standards, and to guarantee enforcement of fundamental labor laws, including workers’ right to form unions.

Since November 2012, at least 1,304 Bangladesh garment workers have been killed and at least 3,877 injured in factory fires and other workplace incidents, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center.

All the more reason, experts say, the Bangladesh government must not roll back international safety inspections.

Says Bilkis Begum: “Surely, we all would agree that it should never be the case that we could sacrifice another Rana Plaza to complete the remaining task of making the workplace safe for the garment workers of Bangladesh.”

Apr 17, 2019

On a recent Friday, the only day off for Bangladesh garment workers—if they get a day off—I went to visit workers at their homes to better understand how the people who stitch our clothes live their lives. Walking through the puzzling narrow alleys, I entered a tin shed-like building. A corridor tore through the center and on each side were rooms for families. It was in one of these dimly lit rooms where I met Konika, who worked as a sewing operator in a nearby garment factory in Gazipur. In the tiny space where she lived with two children and her husband, she revealed the conditions at her workplace.

A garment factory in Gazipur. Credit: Solidarity Center/Istiak Ahmed Inam

“We are under intense pressure to meet the target production,” she says. “I used to produce 70 pieces an hour but now, after our minimum wage has been increased by the government, I must produce 90 pieces. I have to think twice if I want to use the washroom. What if I miss my deadline? What if my production manager sees me? I rest only if there’s a problem with my machine and am lucky if the mechanic is not close by.”

Worker Safety under Threat Again

Six years after the deadly April 24, 2013, Rana Plaza building collapse killed 1,134 garment workers and injured hundreds more, the government is on the verge of rolling back international safety inspections even as employers and the government are blocking workers’ ability to exercise their right to form unions to improve working conditions.

Disasters like Rana Plaza or the 2012 Tazreen Fashions fire, which together killed more than 112 garment workers, prompted global outrage and mobilized workers in protest of unsafe and deadly working conditions, forcing major fashion brands and Bangladesh suppliers to address safety issues. As a result, unions, suppliers and many international brands formed the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, a binding agreement that helped make many garment factories safer. Despite its success, however, the accord may be dismantled, leaving workers at the mercy of a system unprepared to improve factory safety, according to a recent report.

Meanwhile, fashion companies often send their own inspection teams to factories, but the effectiveness of these visits is debatable.

“Our managers make us tell the foreigners [safety inspectors] we don’t work until 10 p.m., that we receive our wages regularly and we even receive our doctor’s fees. None of this is true,” says Konika. On many occasions, the inspection team strolls around the factory, only gathering data from factory management and not from the workers, thus releasing inaccurate reports.

Konika and her co-workers face odds that would dishearten many: factory owners escalating pressure to produce and depriving workers of their basic rights, and corporations wearing a mask of “doing all they can” for workers, while in fact, doing nothing.

Yet Konika, on her day off, enjoys time with her family, despite recognizing the injustices she is likely to face tomorrow.

Dec 13, 2018

More than five years after the Rana Plaza and Tazreen Fashion disasters killed more than a thousand garment workers and injured many more, workers in ready-made garment factories in Bangladesh still struggle to make ends meet. And even now, garment workers often are forced to work in unsafe and unhealthy conditions.

Workers recently interviewed by the Solidarity Center say their employers set harsh production demands with short timelines. In fact, following the government’s recent minimum wage increase from $63 a month to $95, management in some factories pre-emptively set higher production targets. As a result, workers face unbearable pressure to work more quickly and produce more.

Verbal abuse and insults, such as name calling, is routine, workers say.

Many, like Shefali, also suffer from severe health problems after working between 10 and 14 hours per day.

Shefali, who asked that her real name not be used for fear of retaliation, says she is unable to sleep for several hours at a stretch because of pain. Other workers who stand long hours on factory lines say they are unable to sit for extended periods because of joint pain.

Putting Solidarity Center Fire Safety Training into Practice

And for many workers, fire safety is still a danger in many factories. To address the issue, the Solidarity Center’s ongoing fire safety trainings have reached thousands of garment workers, who learn how to extinguish fires, provide first-aid during incidents and safely handle chemicals. They also learn how to identify risks in building safety, abrasions in wiring and machine equipment and how to report those risks to management to help prevent their factories from becoming another Rana Plaza.

The trainings also provide workers with a platform to come together and share their workplace hardships and strategies for improving their work environment.

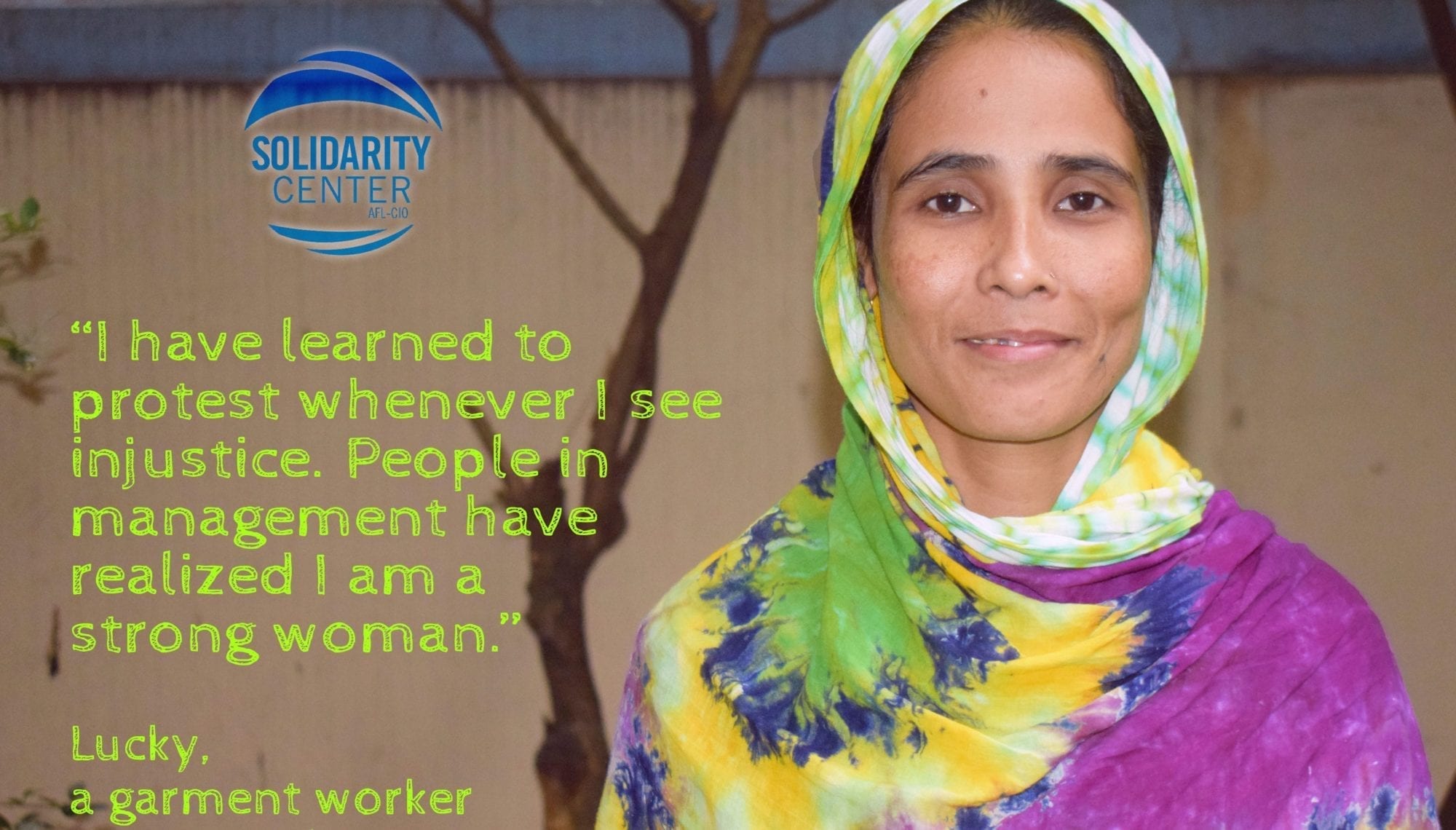

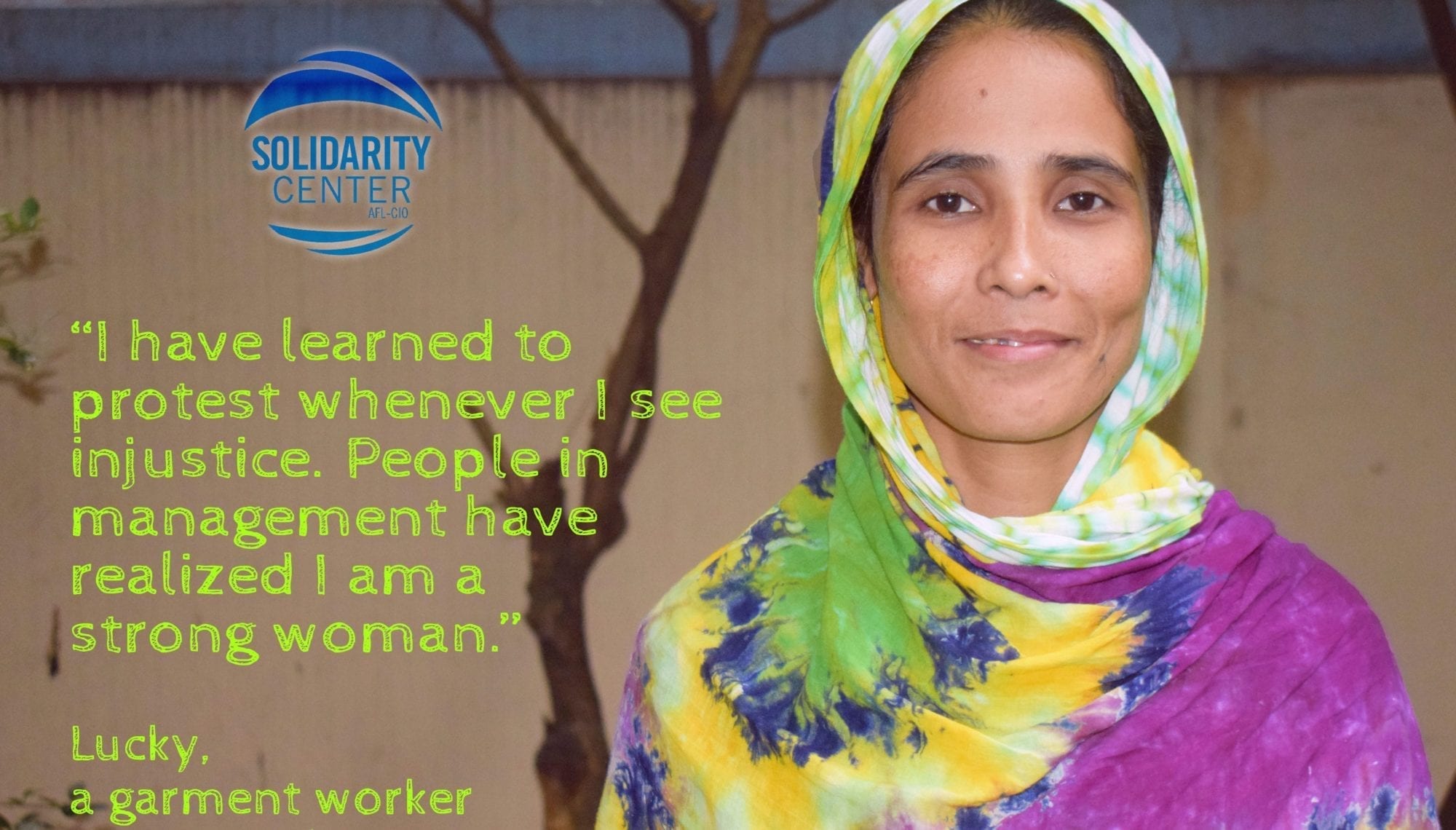

Lucky, who participated in one of the safety trainings, has put the lessons into practice.

“Once, there was fire in our factory and everyone rushed at the gates to escape. I saw a pregnant woman who was injured, and I could not leave her there alone. It is not by fire that people die but from the struggle during escape that causes death. So, I grabbed another colleague of mine and went to her to help. I wrapped my scarf around her as quickly as possible and pulled her out to safety,” she said.

Lucky added: “In another instance, I helped put out a fire at my neighbor’s home when no one could do it. I dipped a sack in the nearby river and threw it over the gas burner. People were amazed and said, ‘How can a woman do this?’ I learned this from all the training sessions I participated in over the years. It was really fruitful as I implemented what I learned a number of times inside and outside of my workplace.”

Apr 15, 2018

Following the Rana Plaza collapse in which 1,134 garment workers were killed and thousands more injured in Bangladesh, the horror of the incident spurred international action and resulted in significant safety improvements in many of the country’s 3,000 garment factories.

But five years after the April 24, 2013, disaster, Bangladesh garment worker-organizers say employers often are not following through to ensure worksites remain safe, and the government is doing little to ensure garment workers have the freedom to form unions to achieve safe working conditions. Since the Tazreen Factory fire that killed 112 garment workers in 2012, some 1,303 garment workers have been killed and 3,875 injured in fire-related incidents, according to Solidarity Center data.

“Five years after the tragedy, the police and local leaders are supporting the factory owners and harassing us”—Tomiza, worker-organizer. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mugfiq Tajwar

“Pressure from the buyers and international organizations forced many changes, says Tomiza Sultana, a garment worker-organizer with the Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation (BIGUF), among them less interference by police and factory management. “ We organized trade unions, recorded complaints and trained many workers.

“But five years after the tragedy, the police and local leaders are supporting the factory owners and harassing us and anyone who wishes to come to us. They have forgotten the lessons of the disaster,” she says.

A Disaster that ‘Cannot Be Described in Words’

“I can vividly recall that day. I can still see the faces of families who were looking for the bodies of their loved ones by only holding their photo ID,” says Nomita Nath, BIGUF president. “This disaster cannot be described in words.” The multistory Rana Plaza building, which housed five garment factories outside Dhaka, pancaked from structural defects that had been identified the day before, prompting building engineers to urge the building be closed. Garment workers who survived the collapse say factory managers threatened their jobs if they did not return to work.

Factory owners did not care about our lives. They only cared about meeting production targets—BIGUF President Nomita Nath. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mugfiq Tajwar

Ziasmin Sultana, a garment worker who survived the collapse, recalls managers telling workers on the morning of April 24 the building was safe even though “the previous day, we had seen cracks [in the building] form right in front of our eyes.” Shortly after starting work, the electricity went out and the building began to violently shake.

After packing into a crowded stairwell to escape, Ziasmin says she found herself falling. “Everything happened in an instant and it was dark everywhere. When I came to my senses, I realized that three of us have survived and everyone else around us was dead.”

“The world saw how much our lives meant to the owners of these factories,” says Nomita. “They did not care about our lives. They only cared about meeting production targets.”

In the wake of Rana Plaza, which occurred months after a deadly factory fire at Tazreen Fashions killed 112 mostly female garment workers, global outrage spurred several international efforts to prevent deaths and injuries due to fire or structural failures. Safety measures were instituted at more than 1,600 factories.

Hundreds of brands and companies signed the five-year, binding Bangladesh Accord on Building and Fire Safety which mandated that brands and the companies they source from fix building and fire hazards and include workers in the process. Many of the signatories recently have signed on to the renewed three-year agreement that takes effect in May. Extending the Accord guarantees that hundreds of additional factories will be inspected and renovated.

Workers Still Struggle to Achieve Safe Workplaces

Maintaining the safety gains made after Rana Plaza is “a big task,” says Khadiza Akhter. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mugfiq Tajwar

In a recent series of Solidarity Center interviews, garment worker-organizers from several national unions applaud the significant safety improvements but warn that employers are backsliding. And workers seeking to improve safety in their factories often face employer intimidation, threats, physical violence, loss of jobs and government-imposed barriers to union registration.

“The Accord contributed to ensuring the safety of the factories, but there is a lot of other work that needs to be done,” says Khadiza Akhter, vice president of the Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF). She and others interviewed say factories are not regularly inspected, employers do not ensure fire extinguishers and other safety equipment are properly maintained, and safety committees sometimes only exist on paper.

“We are now working in this area for maintaining the standard of fire safety. This is a big task in coming future,” Khadiza says.

The Solidarity Center, which over the past two decades in Bangladesh jump-started the process to end child labor in garment factories and served as a catalyst in the resurgence of workers forming unions, in recent years has trained more than 6,000 union leaders and workers in fire safety. Factory-floor–level workers learn to monitor for hazardous working conditions and are empowered to demand that safety violations be corrected. Many workers, in turn, share their knowledge with their co-workers.

Bangladesh at a Crossroads

Garment workers can barely survive with such low wages—Momotaz Begum, worker-organizer. Solidarity Center/Mugfiq Tajwar

Accounting for 81 percent of the country’s total export earnings, Bangladesh’s ready-made garment industry is the country’s biggest export earner. Yet wages are the lowest among major garment-manufacturing nations, while the cost of living in Dhaka is equivalent to that of Luxembourg and Montreal.

“The workers can barely survive with such low wages, as their house rents and even food prices have risen,” says Momotaz Begum, who has worked as a garment worker organizer with the Awaj Foundation since 2008.

Without a union, garment workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace hazards or seek living wages. Worker advocates say Bangladesh is at a crossroads—and they hope the government and employers choose a future in which Bangladesh workers are partners in the country’s economic success and treated with the dignity and respect they deserve.

But even in the face of severe employer harassment and government indifference, worker-organizers like Khadiza, Momotaz, Tomiza and Nomita, all of whom began working in garment factories as children or young teens, are helping workers join together and insist on their rights at work. Today, 445 factories with more than 216,000 workers have unions to represent their interests and protect their rights.

“I believe that the workers must be aware of their rights and they must be united to achieve them,” says Shamima Akhter, an organizer with the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF). “We train them to let them know what they deserve, and we empower them so that they can claim their rights from the factory owners.”

In Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center implements the Workers Empowerment Program – Components 1 and 2, which provides training and rights education to garment workers and organizers, with the support of USAID.

Iztiak, an intern in the Solidarity Center Bangladesh office, conducted the interviews in Dhaka.

Apr 9, 2018

Five years after the deadly Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh, workers and union activists say despite the massive demand from workers for union representation to achieve safe workplaces, worker-organizers must face down threats, harassment and violence to educate workers about their rights on the job.

Shamima Aktar is among Bangladesh garment worker-organizers empowering workers. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mugfiq Tajwar

Since the April 24, 2013, tragedy in which more than 1,130 garment workers died and thousands were injured, the government has approved a little more than half of the garment unions that have applied for official registration, according to Solidarity Center data. Confronted with employers and a government hostile to worker organizations, worker-organizers have sometimes risked their lives to help workers improve wages and working conditions.

Shamima Aktar, a garment factory worker and organizer with Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF), is one of them. During a meeting with management at a newly unionized factory, managers refused to grant a demand made by the factory union that salaries be paid on a timely basis. Instead, Shamima and the other union representatives were locked in the building and beaten, she says.

“But what moved me was that hearing about our abuse, 17 trade unions around the community immediately came to our aid and barricaded the whole factory which we were in. The workers needed us on their side to be able to live in peace and I wish to [keep organizing] no matter how difficult it is for me,” she says.

Through persistence and courage in the face of daunting odds, worker-organizers have helped garment workers form unions despite the severe obstacles. In Bangladesh, more than 200,000 garment workers at 445 factories are represented by unions that protect their rights on the job.

“I have worked day and night, went to gates of factories to talk to the workers, walked with them to their homes to earn their trust and to make them aware of how they are being exploited and deprived of their rights,” says Monira Aktar, an organizer with the Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation (BIGUF). “So far, we have united 2,250 workers into trade unions, and they say that we give them courage and hope. For me, these words are enough to encourage me to work on for them.”

Poverty Wages, Safety Improvements

Thousands of garment workers have participated in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. Credit: Solidarity Center/Rakibul Hasan

Wages in Bangladesh are the lowest among major garment-manufacturing nations, even though the cost of living in Dhaka is equivalent to that of Luxembourg and Montreal. The country’s labor law falls far short of international standards, and the Bangladesh government has failed to enact meaningful legal reforms, including addressing the arbitrary union registration process that is vulnerable to employer manipulation. Without a union, garment workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions.

But due to international action after the Rana Plaza disaster, which occurred months after a deadly fire at Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory killed 112 mostly female garment workers, a variety of efforts to prevent unnecessary deaths and injuries due to fire or structural failures—including the Bangladesh Accord on Building and Fire Safety—have remedied dangers at more than 1,600 factories.

The Solidarity Center has trained more than 6,000 union leaders and workers in fire safety, helping to empower factory-floor–level workers to monitor for hazardous working conditions and demand safety violations be corrected.

Such international attention has opened up space for workers to collectively demand—and win—improvements on the job, says Monira.

“I am proud that we have been able to create leaders among the workers by organizing them into trade unions. In the past this would have been close to impossible.”

In Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center implements the Workers’ Empowerment Program – Components 1 and 2, which provides training and rights education to garment workers and organizers, with the support of USAID.

Iztiak, an intern in the Solidarity Center Bangladesh office, interviewed the worker-organizers in Dhaka.