Mar 28, 2019

In Gulf Cooperation Council countries—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates—amnesties for workers in irregular status are frequently declared, indicating that irregularity is a common and recurring phenomenon within the governing kefala, or work-sponsorship, system. However, even if implemented perfectly, amnesty is a temporary fix, and effective solutions to reduce the population of undocumented migrant workers requires adherence to labor rights principles, according to a new report by the Solidarity Center and Migrant-Rights.org.

The GCC countries are characterized by a majority migrant workforce, tied to their employer-sponsors through kefala. However, for workers whose sponsors fail to renew work visas or for workers who are duped by fake jobs in the recruitment process or who land in untenable and abusive situations, workers “face a series of narrow, unenviable choices and are systematically denied freedoms enshrined in international human rights law,” says the report, Faulty Fixes: A Review of Recent Amnesties in the Gulf and Recommendations for Improvement.

In fact, the report adds: “Migrant workers who are unable to legally leave their job, or leave the country in some cases, are vulnerable to a range of abuses including occupational safety and health violations and gender-based violence as well as non-payment of wages and other forms of forced labor.”

The report has a variety of recommendations for countries of origin and Gulf nations to improve working conditions for migrant workers and to minimize factors that push them into irregular status. Among them: planning and communicating about an amnesty with migrant worker embassies and communities; investigate absent or abusive sponsors; and informing workers about their rights.

See the full report in English and Arabic.

Mar 26, 2019

The Kuwait Trade Union Federation (KTUF) this week celebrated the relaunch of a migrant worker office within its headquarters to help address legal cases related to wage theft or other forms of exploitation brought by migrant workers, including domestic workers, in the country. Two-thirds of Kuwait’s 4.5 million residents are migrant workers, including approximately 660,000 domestic workers.

Millions of migrant workers are trapped in conditions of forced labor and human trafficking around the world, in part as a result of being lied to by labor brokers about the wages and working conditions they should expect. Of the estimated 150 million migrant workers globally, some 67 million labor as domestic workers—83 percent of whom are women—often in isolation and at risk of exploitation and abuse. An International Labor Organization global standard—Convention189 on Domestic Workers—was adopted in June 2011 to protect domestic worker rights.

Domestic worker volunteers from Sandigan-Kuwait, a domestic worker rights organization for Filipino workers, and GEFONT Support Group-Kuwait, an organization for Nepali workers in Kuwait associated with the General Federation of Nepali Trade Unions (GEFONT), will staff the office, encouraging workers to drop in or call to report abuse and request legal assistance from KTUF.

“Nepali laborers abroad have been facing constant suffering, while legal and social rights are not implemented,” says GEFONT Support Group-Kuwait President Ganesh Rawat.

This is the first time that migrant organization volunteers have been invited to participate in the operations of KTUF’s migrant worker office. With support from the Solidarity Center, KTUF will be able to increase its assistance with migrant worker-initiated legal cases.

“The migrant workers’ office opens its doors to all representatives of migrant worker communities, in all categories, to receive complaints,” says KTUF Assistant Secretary General Obeid Menahi Al Ajmi. The federation, he continues, will devote all its resources and tools to support migrant workers, in coordination with the country’s domestic worker department.

The project can be “the avenue on helping each other for the betterment of everyone,” says Sandigan-Kuwait, volunteer organizer, Chito Neri.

Kuwait has been recognized for some important progress on migrant worker issues. A new domestic worker law adopted in 2015, the first in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region, brought the country closer to compliance with internationally recognized labor standards and included a minimum wage and a maximum 12-hour workday, with one day off per week, for migrant workers such as maids, babysitters, cooks and drivers. Kuwait and the Philippines last year signed a new deal that prohibits common employment practices for migrant workers in the Gulf region, including confiscation of passports by employers.

However, migrant workers remain vulnerable to abuse. Changes to employment conditions may be rejected by private employers, who have a financial incentive for maintaining the status quo. A 2017 International Labor Organization study revealed that a significant percentage of employers in Kuwait took steps to prevent their domestic worker from leaving their employ by denying her a day off, refusing to allow her to leave the house unaccompanied or confiscating her passport—all indicators of forced labor. Domestic workers in Kuwait are not yet allowed to join unions to protect their rights.

Given ongoing challenges, unions say that protection of migrant worker rights requires cross-border, collective action. KTUF last month signed a cooperative agreement in Kuwait City with the Central Organization of Trade Unions-Kenya (COTU-K), formalizing the federations’ effort to jointly address issues affecting workers who migrate from Kenya to Kuwait. KTUF signed a cooperation agreement with the Nepalese Workers’ Union in April last year, committing to joint action in support of worker rights.

The KTUF is an important actor at the national policy level, maintaining a vigorous presence in deliberations on proposed labor law reform, economic restructuring, trade union rights and democratic freedoms. The Solidarity Center supports Kuwaiti unions’ active role in cross-regional collaborations, as well as capacity building programs for Kuwait Trade Union Federation (KTUF) affiliates in the civil service and oil sectors.

Feb 21, 2019

The Central Organization of Trade Unions-Kenya (COTU-K) and the Kuwait Trade Union Federation (KTUF) signed a cooperative agreement last week in Kuwait City, formalizing the federations’ effort to jointly address issues affecting workers who migrate from Kenya to Kuwait for employment.

“It is crucial to bring together unions from countries on both ends of the migration spectrum to promote a deeper understanding of the challenges workers face along their journey and into the workplace,” said Solidarity Center Director of Middle East and North Africa Programs Hind Cherrouk. “This agreement, which affirms the rights of migrant workers from Kenya in Kuwait, is an important step forward in that regard.”

Millions of migrant workers are trapped in conditions of forced labor and human trafficking around the world, in part as a result of being lied to by labor brokers about the wages and working conditions they should expect. Of the estimated 150 million migrant workers globally, some 67 million labor as domestic workers—83 percent of whom are women—often in isolation and at risk of exploitation and abuse.

The majority of some 34 million Africans are migrants move across borders in search of decent work—jobs that pay a living wage, offer safe working conditions and fair treatment. Often they find employers who seek to exploit them—refusing to pay their wages, forcing them to work long hours for little or no pay, and even physically abusing them. Kenyan women signing on for domestic work in Saudi Arabia, for example, were told they would receive 23,000 Kenya shillings ($221) a month, only to find upon their arrival that the pay was significantly less and the working and living conditions inhumane. Through the Kenya Union of Domestic, Hotel, Educational Institutions, Hospitals and Allied Workers (KUDHEIHA), COTU-K is supporting a multi-year effort to protect domestic workers migrating from the coastal area surrounding the city of Mombasa to homes in the Middle East.

Unions around the globe are increasingly taking joint action to create community and workplace-based safe migration and counter-trafficking strategies that emphasize prevention, protection and the rule of law. KTUF spearheaded a groundbreaking 2015 domestic worker law that granted enforceable legal rights to 660,000 mostly migrant workers from Asia and Africa working in Kuwait as domestic workers, nannies, cooks and drivers, and urged further protection for migrant workers in Kuwait and other Gulf countries. That same year, unions in Asia and the Gulf signed a landmark memorandum of understanding (MOU) that promoted and outlined steps for coordination among unions in organizing and supporting migrant workers in those regions. The Solidarity Center and its partners in the Americas in 2017 crafted a worker rights agenda for inclusion in the United Nations Global Compact on Safe, Regular and Orderly Migration.

“There is a potentially powerful role for union-to-union, cross-national and, in this case, cross-regional solidarity in protecting the dignity of migrant workers traveling from Africa to the Middle East. The Solidarity Center is proud to be a partner in this process and trade union-centered approach between the trade union movements of Kuwait and Kenya,” said Solidarity Center Director of Africa Programs, Hanad Mohamud.

Jul 6, 2015

There is some good news for domestic workers in Kuwait: The National Assembly adopted a new law in June that will grant them unprecedented legal rights. The law applies to family maids, baby sitters, cooks and drivers.

More than 660,000 domestic workers are currently employed in Kuwait, most of them migrant workers from Asia and Africa. Human Rights Watch researcher Rothna Begum says this is a “major step forward” for Kuwait because for the first time it provides domestic workers with “enforceable labor rights.”

“Now those rights need to be made a reality,” she says, “and other Gulf states should follow Kuwait’s lead.”

Under the law, which brings Kuwait closer to compliance with internationally recognized labor standards, employers must grant domestic workers a maximum 12-hour workday with one day off per week and 30 days paid leave per year. The law also establishes a minimum wage of 45 Kuwaiti Dinar (around $150), guarantees end-of-service benefits—one month’s wage for every year worked—and bans employing domestic workers who are below age 20 or more than 50 years of age.

The National Assembly also voted to establish a shareholding company for recruiting domestic workers. The company would replace more than 300 independent offices, streamlining the recruitment process and limiting potential abuse of domestic workers. The assembly also voted to create Kuwait’s first National Human Rights Commission.

Begum, however, pointed out that some legal gaps remain. For example, it is not yet clear how the law will be enforced, and domestic workers still are not allowed to join unions to protect their rights.

Abdulrahman al-Ghanim, a migrant worker advocate at the Kuwait Trade Union Federation (KTUF), says the law should only be the beginning. Migrant workers especially are in need of further protection, he says. In Kuwait and other Gulf countries, the current Kafala system—in which recruitment agencies sponsor migrant visas—makes it easy for employers to abuse domestic workers and then charges workers as criminals when they try to escape. Kafala is “a system of slavery,” he says.

“The new legislation is a start,” says Begum, pointing out that the law still does not match the standards for domestic workers established by the International Labor Organization (ILO). “Kuwait should continue improving protections for domestic workers,” she says.

Jun 16, 2015

On a trip to Kuwait two years ago, Nisha Varia from Human Rights Watch visited a hospital where two rooms were filled with injured domestic workers who had tried to escape from their employers’ homes. Trapped in abusive situations, the women jumped from windows or were beaten by employers as they sought to leave.

The experience for domestic workers in Middle Eastern Gulf states, and in many countries around the world, has not significantly improved since then, said Varia and others at a recent panel in Washington, D.C., “Migrant Workers in the Gulf States: Transnational Policy Responses to Protect Labor Rights.”

In the Gulf, “employers feel they have bought domestic workers because they paid the recruitment fee,” Varia said. The situation is exacerbated in Gulf countries by the kefala system, which ties employment of foreign workers to their employers, and makes it illegal for workers to get another job in the country. Employers also typically take the passports of domestic workers, who toil unseen from the public and are especially vulnerable to abuse.

June 16, International Domestic Workers Day, marks the fourth anniversary of the adoption of the United Nations Convention 189 on Domestic Workers, a landmark standard championed by unions, civil society groups and human rights organizations worldwide. Its passage signaled the global community’s recognition that the 53 million workers who labor in households, often in isolation and at risk of exploitation and abuse, deserve full protection of labor laws.

The historic action indicated the recognition that domestic workers, 83 percent of whom are women, perform work—and that entails rights equal to all other wage earners. Eighteen countries have ratified the Convention since its passage. (ILO resources for and information on domestic workers here.)

The panel, which encompassed broader issues of labor migration, highlighted the overlap between domestic workers and migrant workers. The Solidarity Center works with domestic workers in countries such as Dominican Republic, where most domestic workers are from Haiti and in Jordan, where domestic workers have migrated for work from the Philippines, Malaysia and other countries.

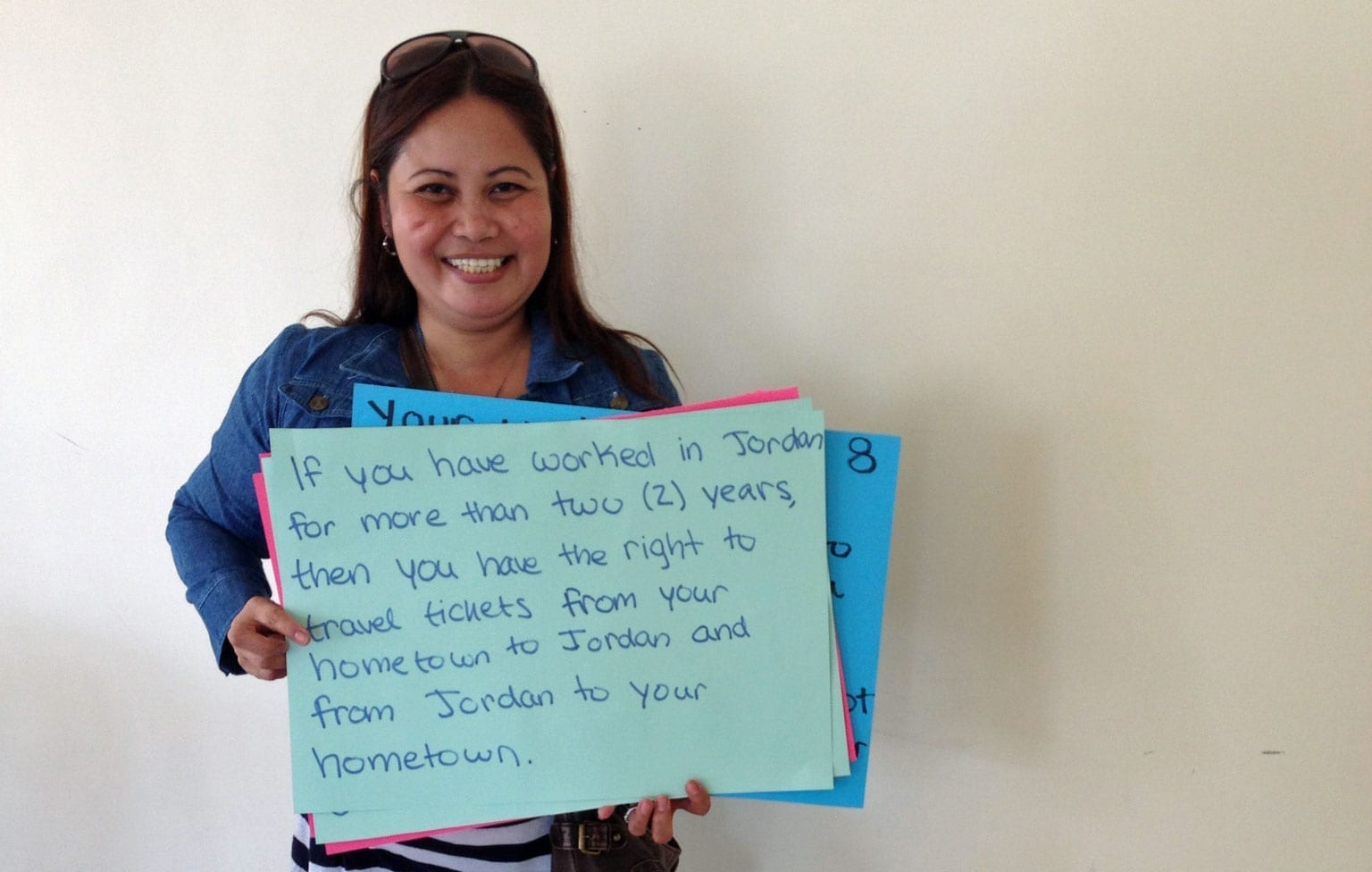

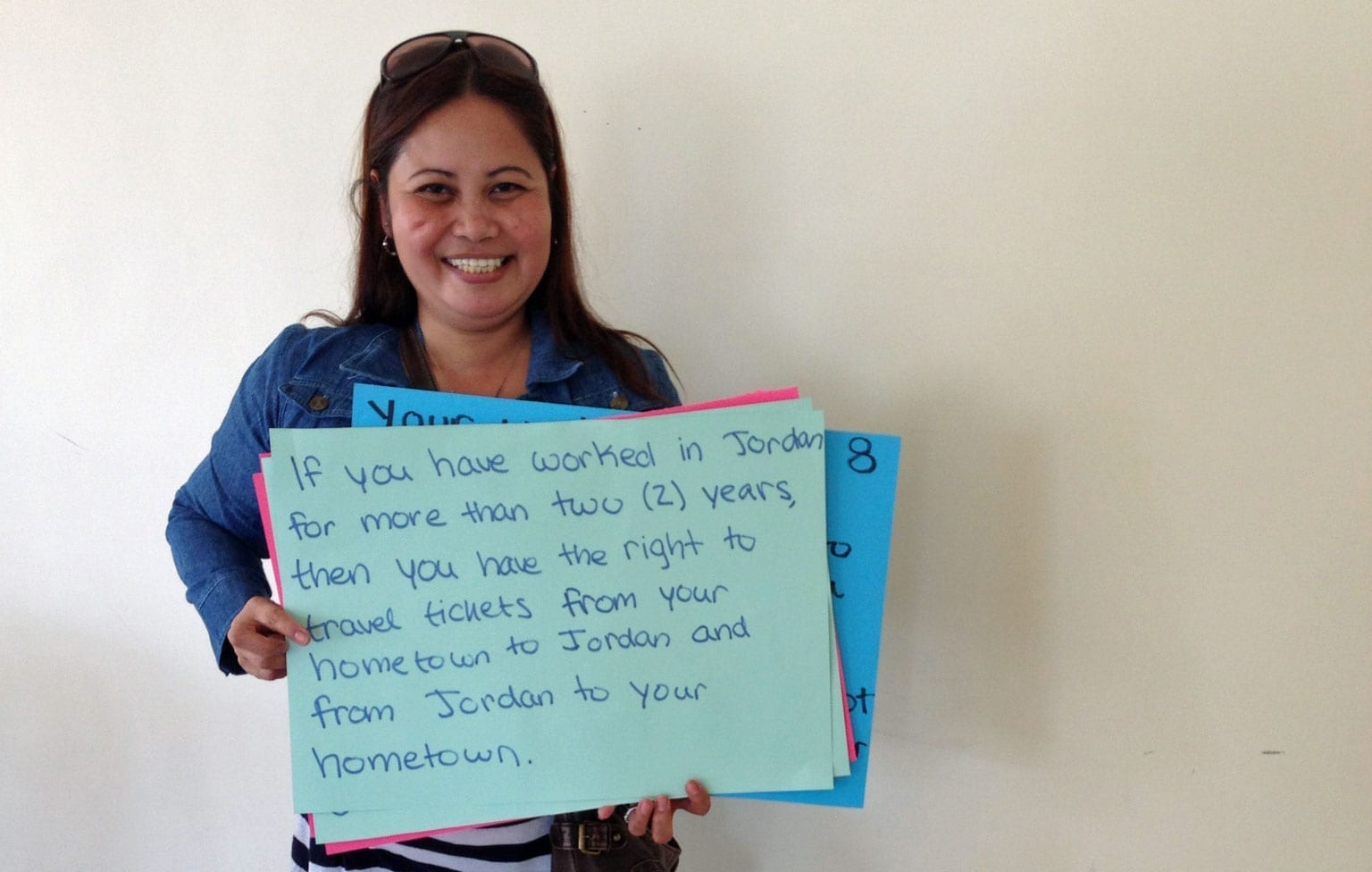

In Jordan, the Solidarity Center is assisting domestic workers build support for their rights on the job. In a first-of-its-kind network, some 250 domestic workers meet regularly, with translation conducted simultaneously in three, or sometimes four, languages. The Domestic Workers Network in Jordan is cooperating with the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF), which formed to help push the ILO Domestic Workers convention and which now represents workers around the world.

Panel participants pointed to the common experiences of those who migrate for jobs, especially domestic workers. After they arrive in the destination country, their cell phones often are confiscated and contact with their families is limited. They are completely excluded from the country’s labor laws, typically do not get any days off and generally do not receive the wage they were promised.

Varia likened the experience of migrant domestic workers to abusive domestic violence situations in which employers exert power by withholding food from domestic workers and force them to sleep on the floor or in closet-like spaces.

In their studies, panelists found that when migrant workers understand their rights before they migrate, they are more likely to leave abusive situations quickly, indicating the value of programs that educate domestic workers and other potential migrants in their home countries.

A better solution, they agreed, is the availability of employment at home.

“If people could find good jobs, they wouldn’t migrate,” Varia said.

Other panelists included: Mahendra Pandey, a former migrant worker; Sarah Paoletti, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Transnational Legal Clinic; and Eleanor Taylor-Nicholson, an independent consultant on migrant worker rights. Shannon Lederer AFL-CIO director of immigration policy, moderated the panel, sponsored by the AFL-CIO and Solidarity Center.