Sep 21, 2018

Of the 152 million children forced to work around the world, nearly half—73 million—are engaged in hazardous work, which includes dangerous, unsafe working conditions, and work that exposes children to physical, psychological or sexual abuse, according to the U.S. Department of Labor 2017 Findings of the Worst Forms of Child Labor report released yesterday. In 2015, 168 million children labored worldwide.

Most child labor—some 70 percent—occurs in agricultural

sectors, but it takes place in all industries. While the global trend in child

labor is downward, in sub-Saharan Africa the proportion of children in child

labor is actually rising—with one in five children engaged in child labor,

according to the report. Some 48 percent of child laborers were younger than

age 12.

The report also assesses countries’ progress in reducing child labor and found that three countries—Burma, Eritrea and South Sudan—received a “no advancement” assessment due to their government’s direct or active involvement in forced child labor. In total, 12 countries were assessed as making no advancement.

After years of receiving an assessment of “no advancement” for the forced mobilization of children in the cotton harvest, Uzbekistan received a “moderate advancement” for progress in reducing child labor. But the U.S. Department of Labor continues to call for an end to the mobilization of adult forced labor in cotton harvests. The Dominican Republic also received an assessment of “moderate advancement” because, in contrast to previous years in which it received an automatic “minimal advancement,” no cases were reported of children withoutidentity documents being denied access to education, an unlawful practice that mainly targeted children of Haitian descent.

Eswatini (formerly known as Swaziland), moved from “no advancement” to “minimal advancement” because there was no evidence in 2017 that local chiefs were forcing children to perform agricultural work or other tasks through kuhlehla, a customary practice that requires residents to carry out communal work, including in chiefs’ houses or fields.

The report highlighted work by the Global March on Child Labor, which organized a virtual march in May and June 2018 to commemorate its 20th anniversary and spread awareness about hazardous child labor and the safety and health of young workers. The Global March, a Solidarity Center partner, is headed by Kailash Satyarthi, who won a Nobel Prize in 2014 for his lifetime commitment to the cause of eradicating child labor. Solidarity Center Asia Regional Director Tim Ryan chairs the Global March board of directors.

The Labor Department also released its annual List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, which documents more than 140 goods produced by child labor or forced labor in violation of international standards. Ten new goods were added to the 2018 list, including amber, cabbage, carrots, cereal grains, lettuce and sweet potatoes.

The “Worst Forms of Child Labor” report is required under

the 2000 Trade and Development Act (TDA), and the List of Goods Produced by

Child Labor or Forced Labor was first published in 2008, as mandated by the

Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act. Both acts aim to promote

global economic growth and build strong international trade partnerships that

hinge upon the reduction of child labor, forced labor and human trafficking.

Jun 13, 2018

“I have one single mission: Every child should be free to be a child.”

Nobel Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi proclaimed this ambitious mission in the new documentary, Kailash, which depicts the fight to end child labor through the Global March Against Child Labor and Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA), the organizations Satyarthi founded.

In 1994, 150 child labor advocates marched through the southern tip of India chanting, “No more tools in tiny hands. We want books, we want toys,” marking the beginning of a revolution to end child labor. Four years later, Satyarthi and other child labor advocates founded the Global March.

Tens of thousands of children in child labor have been rescued through organizations founded by Nobel winner Kailash Satyarthi. Courtesy: “Kailash”

“We were led by young people, many of whom were child laborers,” said Anjali Kochar, executive director of the Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation. Kochar spoke at the U.S. Department of Labor, one of several locations in Washington, D.C., where the documentary was screened to commemorate 2018 World Day Against Child Labor on Tuesday.

“They demanded their right to childhood,” said Kochar, recalling the march. “They called for the elimination of child labor and for meaningful, quality education. It was truly electrifying.”

Satyarthi began rescuing child laborers in the 1980s. His first rescue attempt was unsuccessful because he was outgunned by human traffickers. Satyarthi then brought to court photos of the atrocities he saw when trying to rescue the children, and a judge then ordered they all be freed.

The more children rescued, the bigger the mission became until more than 200 activists, lawyers and social workers joined Satyarthi in the 1980s to form the BBA, an India-based organization that has rescued more than 80,000 child laborers. Mukti Ashram, the Delhi branch of BBA, provides shelter and education for liberated children.

Demand for Cheap Products Increases Demand for Child Labor

Satyarthi looked at the successes of Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, and Martin Luther King Jr. and decided that a “global march” was best for bringing attention to a global problem. The increased demand for cheap products was leading to an increased demand in cheap labor, making abuse and wage theft common in supply chains, especially for women and children. Since The Global March Against Child Labor formed in 1998, the International Labor Organization (ILO) passed Convention 182 on elimination of the worst forms of child labor, child labor in homes was banned in India in 2006 and the South Asian March Against Child Trafficking took place in 2007, where 1 million people marched 3,000 miles to end forced labor.

Although the efforts of Satyarthi, who won the Nobel Prize in 2014 for his efforts, and other global advocates decreased the number of child laborers from 260 million to 152 million in 20 years, there is still more work to be done. Of the 152 million child laborers, 73 million work in hazardous conditions. These children are between the ages of 5 and 17, spending their days in factories and fields instead of in school.

The film reveals the complexity of child labor, illustrating how poverty and education often underly child labor. Parents who are paid very little or are unemployed may need their children to work so their families can survive. Because of the lack of resources, impoverished parents are often uneducated and their children fall prey to traffickers promising work opportunities. The children are taken from their families and forced to work for months or years, escaping with burns and broken bones. This was the case for Sanjeet, who appeared in the film and was rescued by BBA. This young boy was found with dents in his face from hot powder blown by fans in a factory. He had not been allowed to go home in a year.

Acknowledging prior accomplishments as well as the work ahead, Satyarthi created the 100 Million Campaign in 2016, which seeks to mobilize 100 million young people to fight for 100 million child laborers. This program will not only benefit the children still suffering under forced labor but will provide a legacy so that future generations can continue to tackle this issue.

“We all have to work to globalize compassion,” says Satyarthi when discussing how movements make change. “Every child has the right to bread, education, love and play.”

Jun 6, 2018

On a warm, dusty day on the Deccan plateau in April 1994, I joined Kailash Satyarthi’s Bharat Yatra, (Indian Journey), a group of 150 child labor activists part-way through its march from the southern tip of India to the heart of New Delhi, where it would arrive five months later. I didn’t realize it then, but I was witnessing the prototype of the movement that Kailash would take to a global scale four years later, and result in the biggest single step forward in history in the cause to abolish child labor.

It was hard to visualize 24 years ago that these initial attempts to mobilize masses of people behind a broad social movement would build to this moment today—a 20th anniversary commemoration at the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) annual Conference in Geneva of the Global March, which ushered in ILO Convention 182 aimed at eliminating the worst forms of child labor.

ILO conventions set a global standard for labor rights that UN member countries are expected to adopt and enforce. Not all countries are willing to do so. But Convention 182 is now the most ratified convention in ILO history, with 181 signatory countries. As one diplomatic observer in the early 1990s said to me, looking at the burgeoning activity in India, “Kailash has built a movement—now he needs to build an organization.”

Build one he did. The Global March Against Child Labour was formed 20 years ago specifically to mobilize people worldwide to lobby for adoption of Convention 182. And finally recognizing his decades-long campaign to abolish child labor, the Nobel Committee awarded Kailash the Peace Prize in 2014.

At the commemoration this week, attended by hundreds of delegates from governments, employers and trade unions, Kailash was joined by ILO Director General, Guy Ryder, representatives of workers’ and employers’ groups, and two very special guests: Basu Rai, a former child laborer who, as a 9-year-old, was one of the original marchers who came to Geneva 20 years ago, and Zulema Lopez, a former child farm worker in the United States, who is now earning a university student.

Opening the program, Ryder noted to Kailash, “I personally remember the moment, the incredible moment 20 years ago, when you led children from around the world into the ILC to press for Convention 182.” He pointed out that even though child labor has been reduced by tens of millions since that time, 152 million children are still working, with practically no reduction in the 5–11 year age range. Indeed, hazardous child labor for that age cohort has actually increased. With the number of children injured and killed each year in hazardous labor conditions, Ryder said, “If this were a war, we’d be talking a lot more about it.”

Basu, in an impassioned address, talked about how he was orphaned at 4, joined a street gang and became a child slave before being rescued by Kailash and his activists. “I remember coming here 20 years ago and climbing on the desks and raising the slogan, ‘No more tools for tiny hands, we want books, we want toys.’ My childhood was snatched away. I’m coming here today, but I’m still afraid. I’m still afraid—and I’m a father to a 2-month-old daughter—that the world is not safe for the children.”

Zulema told the assembly: “I was a third-generation farm worker family. I first went to work in the fields when I was 7. I missed school. It was normal for me to wake up at 5:30 in the morning, put on a T-shirt, and work for hours in the hot sun, my back aching from carrying 30 pounds of cucumbers.”

In winding up the event, Kailash reminisced, “I remember that day when I walked in with the core marchers of the Global March who were allowed to come into the ILO, which was the first time in history the ILO opened its doors to the most exploited and most vulnerable… We were marching from exploitation to education.”

While there has been progress, much work needs to be done to eliminate child labor, as envisioned by the UN-adopted Sustainable Development Goals, by 2025.

“Child labor is not an issue that will be solved by someone else; it’s up to you personally,” said Kailash. “It’s urgent. The childhood of children today can’t wait. And you have to believe it’s possible. It’s personal, it’s urgent, it’s possible.”

Timothy Ryan is the Chairperson of the Global March Against Child Labour and the Asia Regional Director for the Solidarity Center.

Nov 8, 2017

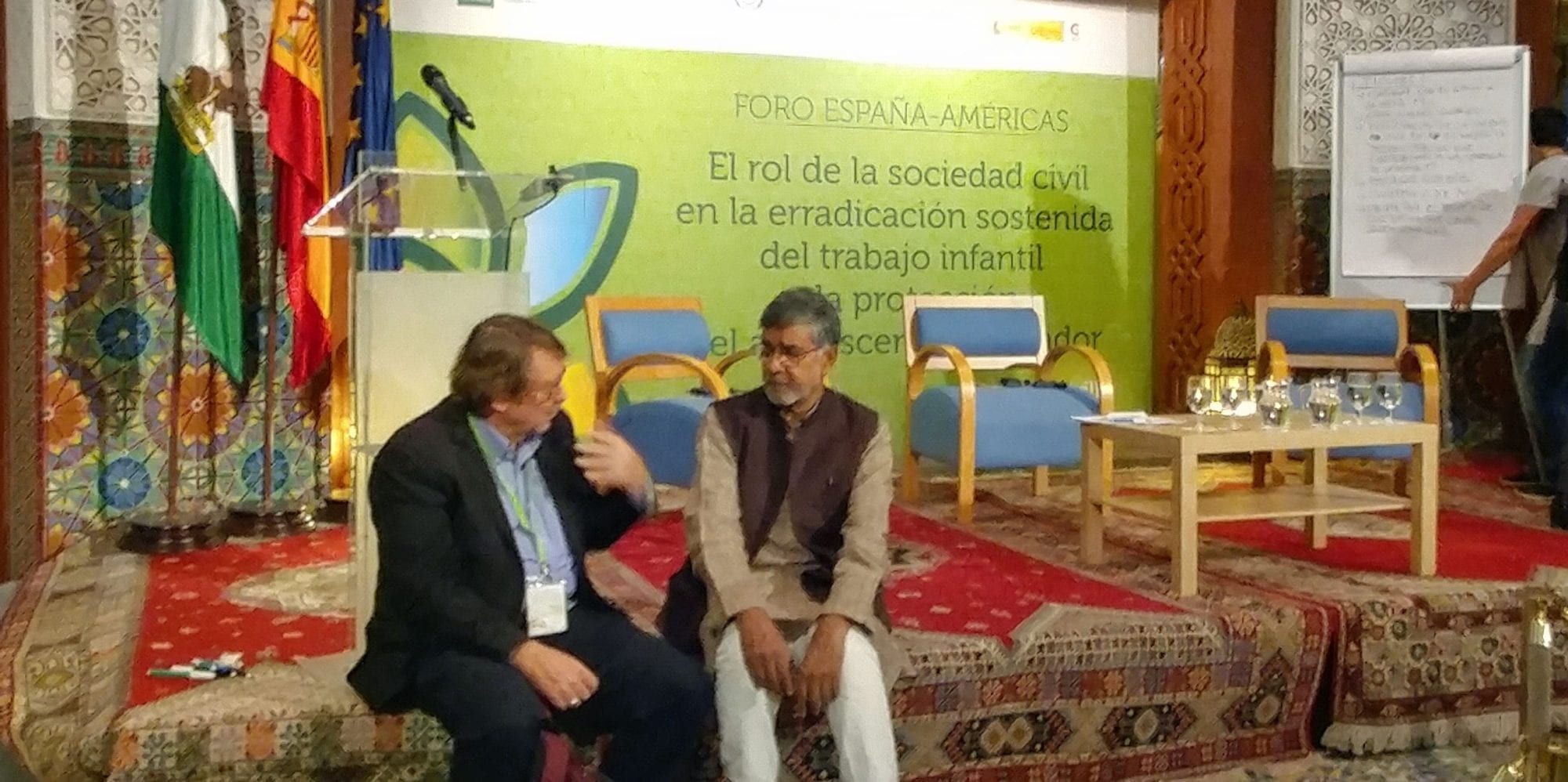

“Trade unions and NGOs must work together” to end child labor, asserted Nobel Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi as he summed up a two-day gathering of more than 40 child labor activist organizations from around the world in Seville, Spain. Participants at “Forum Spain-Americas: Civil Society for the Sustained Elimination of Child Labor” met last week to discuss United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 8.7, which aims in part at the eradication of child labor.

Satyarthi, founder of the Global March Against Child Labor, a worldwide network of trade unions, civil society organizations and education associations working to end child labor, launched the organization 20 years ago to press for adoption of International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 138 on eliminating the worst forms of child labor.

“The Global March started out as a movement, which became an organization,” said Solidarity Center Asia Region Director Tim Ryan. “You can identify an issue and create an organization, but you need a vision to create a movement.” Ryan, who serves as chairperson of the Global March Against Child Labor, participated in a panel examining how the Global March’s international work over the years could inform renewed efforts to address child labor in the Western hemisphere.

Ending Child Labor, Ensuring Children Receive Quality Education

The connection of trade unions and civil society organizations in a close partnership has been a unique and important aspect from the inception of Global March, Ryan said. Currently, representatives from Education International, the global union federation of teachers, and trade union activists from Ghana and the United States are Global March Board members.

“It’s no surprise teachers’ unions around the world are part of the Global March,” Ryan said. “A key value underpinning the elimination of child labor has to be the opportunity for children to have a quality education.”

Satyarthi said that education philosophy around the world must be aimed at something greater than turning out consumers.

“Education that just produces makers and lubricators of the global economy is a disaster,” he said. But “there is no dearth of good people and good work who can strengthen our alliances with hope and resolve” to eliminate child labor with committed people and their organizations working for it.

The meeting, a joint initiative of the Spanish Andalusian Agency for International Development and the ILO to work together on strategies to eliminate child labor, sets the stage for the ILO Global Conference on the Sustained Eradication of Child Labor meeting this week in Argentina.

Aug 10, 2017

Kailash Satyarthi, a Solidarity Center ally, won the Nobel Prize in 2014 for his lifelong efforts to end child labor. He began this work much earlier, in 1986 in Jharkand province—one of India’s poorest regions at the time, a place where child labor was common across a variety of industries.

Since then, Satyarthi has freed more than 80,000 children. His movement, the Global March Against Child Labor, has given rise to an international network of grassroots activists spread across multiple issue areas, all combatting child exploitation. In 2015, Satyarthi delivered a petition to United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon demanding that the abolition of child labor be made a Sustainable Development Goal. More than 550,000 people around the world signed it, ensuring that Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8.7 against child labor exists today.

Recently, Satyarthi was in Washington, D.C., to address congressional lawmakers on the situation of child labor globally. The Solidarity Center spoke with him about his Foundation’s work and the role of the labor movement in combating child exploitation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve been fighting child exploitation since the 1980s. How has child labor changed in this time?

Kailash Satyarthi Credit: Global March Against Child Labor

Satyarthi: The world has grown rapidly, but despite technological advancements and accumulating vast global wealth, we have not been able to safeguard our children’s freedom. Today, 168 million languish in labor while 5.5 million are enslaved. Two hundred and thirty million children are caught in conflict-prone environments. Approximately 21 million children today have been displaced and face poverty, violence and inhumane conditions. Globalization has presented new challenges: increased cyber-crime and violence against women and children perpetrated online.

But the internet has made activism more sustainable. People are more inclined to support this fight because of increased awareness and ease of access. With the advent of technology, we have been able to make significant progress. I believe if the power of the internet and young people are channeled properly, we will be able to bring justice into the lives of many children.

What role does the labor movement play in the fight against child labor?

Satyarthi: To fully realize the SDGs, the fulfillment and protection of the rights of children is central. Trade unions are indispensable to this mission in two ways.

First, while workers in developed nations often receive their fair and just share, their counterparts in poor nations or emerging economies are denied what is theirs by right. This creates formidable challenges, like struggling to meet daily nutrition requirements. Poor laborers then seek another pair of working hands; in most cases, it is their child’s. A strong trade union can deliver the promise of decent work and income to families and so protect the development of these children.

Second, while 168 million children labor globally, 200 million adults are unemployed. Labor unions can help organize legal employment for these adults, as there is clearly no dearth of jobs. There are no easy solutions, but we know by experience that with the strength and resilience of labor unions, we can reach many who are voiceless working in illegitimate parallel economies.

As you noted, stable, well-paying jobs are hard to find for workers of all ages. What is the relationship between the ongoing flexibilization of work and the prevalence of child labor?

Satyarthi: Unfortunately, the concept of a fixed job is being wiped out by the relentless pressures of globalization while the movement of labor remains tightly restricted. Until the 1980s, in a country like the United States, people expected to work in a factory or office, in semi-skilled or skilled jobs until retirement. That is no longer true. It has been replaced by a concept of labor which takes us back, in some ways, to the 19th century when workers lacked job security. In this situation, it’s difficult to send children to schools and colleges. Rather, children end up working to help supplement uncertain family incomes.

What can be done to ensure that children, especially those in rural areas, are protected?

Satyarthi: Traditionally, the prevalence of child labor in farms has been widespread, meaning from children helping their families to bonded labor. Today, in relatively poor countries like India, where 50 percent of the population depends on agriculture for a livelihood, the most common form of child labor is found in farms. Until recently, it was rare to find a functional school in rural India. Some children were forced to walk over 10 kilometers (about 6 miles) to attend schools where teacher absenteeism was rampant. Here, government intervention is necessary. Education is a fundamental right and a public good and cannot be left at the mercy of market forces and private players. We have seen welfare schemes that guarantee employment to poor rural Indians and free meals to children attending school lead to a dramatic improvement in school enrollment. Much more needs to be done.

Over your career, you’ve used many strategies to fight child labor. What initiatives stand out to you as you look back on your career?

Satyarthi: During the first phase of my fight in the 1980s, the world remained ignorant as 250 million children labored globally. In the South Asian carpet industry alone, the number of child slaves working as carpet weavers was slightly over a million. Despite conducting many on-the-ground raid and rescue operations, we were not making desirable progress.

In 1995, I started discussions with carpet manufacturers, middlemen, exporters, NGOs in India and elsewhere, and leading carpet importers in Germany and the United States. This became the inspiration behind GoodWeave. The idea was to eradicate child labor in the carpet manufacturing industry with well-placed interventions in the supply and demand chains. I believed that after sparking the will for change, the industry could help social development by disrupting the circle of poverty, illiteracy, poor health and illegal employment.

What do you say to skeptics of GoodWeave and other consumer-based approaches to promoting human rights?

Satyarthi: GoodWeave effected a decline in child labor in the carpet industries, from over a million in the 1990s to less than 200,000 today. The most remarkable fact is that there was no decline in rug exports. Optimism among stakeholders brought about a remarkable change channeled through the power and reach of the corporate sector. If corporate and civil society can learn from our experiences with consumer-based human rights advocacy, then we can usher in a new era of globalization.

What about arguments that socially progressive policies, like compulsory universal primary education or a living wage, place an unfair economic burden on developing countries?

Satyarthi: The positive effect of placing children at the heart of policy and action is evident. If all students in low income countries acquired basic reading skills, 171 million people could be lifted out of poverty, equivalent to a 12 percent cut in world poverty. Moreover, an investment of one dollar in the eradication of child labor gives you the return of $10 to $15 in 10 years. The same applies to investment in education: Every additional year of schooling a young person receives increases their average future earnings by 10 percent, and can boost countries’ average annual GDP (gross domestic product) growth by 0.37 percent.

So, I humbly appeal to the naysayers to focus on what is measurable. Child labor never did any family or any child any good. It has to go.